Internment of German Americans

It has been suggested that this article be merged with World War II related internment and expulsion of Germans in the Americas. (Discuss) Proposed since October 2011. |

German American Internment refers to the detention of people of German citizenship in the United States during World War I and World War II. Unlike the Japanese Americans who were interned during the war, they have never received an apology or reparations.[1] However, unlike Japanese-Americans, who were rounded up whether citizens or not, only non-citizen Germans were rounded up.

World War I

Civilian internees

President Woodrow Wilson issued two sets of regulations on April 6, 1917, and November 16, 1917, imposing restrictions on German-born male residents of the United States over the age of 14. The rules were written to include natives of Germany who had become citizens of countries other than the U.S.[2] Some 250,000 people in that category were required to register at their local post office, to carry their registration card at all times, and to report any change of address or employment. The same regulations and registration requirements were imposed on females on April 18, 1918.[3] Some 6,300 such aliens were arrested. Thousands were interrogated and investigated. A total of 2,048 were incarcerated for the remainder of the war in two camps, Fort Douglas, Utah, for those west of the Mississippi and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, for those east of the Mississippi.[4]

The cases of these aliens, whether being considered for internment or under internment, were managed by the Enemy Alien Registration Section of the Department of Justice, headed beginning in December 1917 by J. Edgar Hoover, then not yet 23 years old.[5]

Among the notable internees were the geneticist Richard Goldschmidt and 29 players from the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[6] Their music director, Karl Muck, spent more than a year at Fort Oglethorpe, as did the music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Ernst Kunwald.[7] One internee described a memorable concert in the mess hall packed with 2000 internees, with honored guests like their doctors and government censors on the front benches, facing 100 musicians. Under Muck's baton, he wrote, "the Eroica rushed at us and carried us far away and above war and worry and barbed wire."[8]

Most internees were paroled on the orders of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer in June 1919.[9] Some remained in custody until as late as March and April 1920.[10]

Merchant marine vessels

Until the U.S. declared war on Germany, German commercial vessels and their crews were not detained. In January 1917, there were 54 such vessels in mainland U.S. ports and one in San Juan, Puerto Rico, free to leave.[11] With the declaration of war, 1800 merchant sailors became prisoners of war.[12]

Military internees

Before the U.S. entered the war, several German military vessels found themselves in U.S. ports, where authorities ordered them to leave within 24 hours or submit to detention. The crews were first treated as alien detainees and then as prisoners of war (POWs). In December 1914 the German gunboat Cormoran, pursued by the Japanese Navy, tried to take on provisions and refuel in Guam and the commanding officer, when denied what he required, accepted internment as enemy aliens rather than return to sea. The ship's guns were disabled. Most of the crew lived on board, since there were no housing facilities available. During the several years the Germans were detainees, they outnumbered U.S. marines in Guam. Relations were cordial, and a U.S. Navy nurse married one of the Cormoran's officers. As a result of U-boat attacks on U.S. shipping, the U.S. broke off diplomatic relations with Germany on February 4, 1917, and U.S. authorities in Guam imposed greater restrictions on the German detainees. Those who had moved to quarters on land returned to the ship. Following the U.S. declaration of war on Germany in April 1917, the Americans demanded "the immediate and unconditional surrender of the ship and personnel." The German captain and his crew blew up the ship, taking several German lives. Six whose bodies were found were buried in the U.S. Naval Cemetery in Apra with full military honors. The surviving 353 German service members became prisoners of war, and on April 29 were shipped to the U.S. mainland.[13] Non-Germans were treated differently. Four Chinese nationals became personal servants in the homes of wealthy locals. Another 28, Melanesians from German New Guinea, were confined on Guam and not accorded the rations and monthly allowance that other POWs received.[14] The crews of the cruiser Geier and an accompanying supply ship, which sought refuge from the Japanese Navy in Honolulu in November 1914, were similarly interned until they became POWs.[15]

Several hundred men on two other German cruisers, the Prinz Eitel Friedrich and Kronprinz Wilhelm, unwilling to face the British Navy in the Atlantic, lived for several years on their ships in various Virginia ports and frequently enjoyed shore leave.[16] Eventually they were given a strip of land in the Norfolk Navy Yard on which to erect accommodations. They constructed a complex commonly known as the "German village" with painted one-room houses and fenced yards made from scrap lumber, curtained windows, and gardens of flowers and vegetables, as well as a village church, a police station, and cafes serving non-alcoholic beverages. They rescued animals from other ships and raised goats and pigs in the village along with numerous pet cats and dogs.[17] On October 1, 1916, the ships and their personnel were moved to the Philadelphia Navy Yard along with the village structures,[18] which again became known locally as the "German village." In this more secure location in the Navy Yard at Philadelphia's League Island behind a barbed wire fence, the detainees designated February 2, 1917, Red Cross Day and solicited donations to the German Red Cross.[19] As German-American relations worsened in the spring of 1917, nine successfully escaped detention, prompting Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels to act immediately on plans to transfer the other 750 to detention camps at Fort McPherson and Fort Oglethorpe in late March 1917,[20] where they were isolated from civilian detainees.[21] Following the U.S. declaration of war on Germany, some of the Cormoran's crew members joined them at McPherson, while others were held at Fort Douglas, Utah, for the duration of the war.

World War II

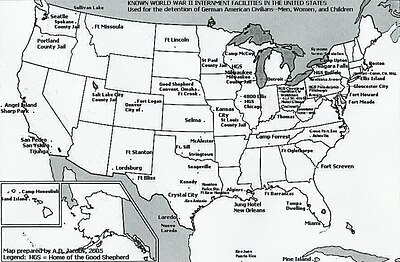

At the start of World War II, under the authority of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, the United States government detained and interned over 11,000 German enemy aliens. They were all either former civilians or citizens of Germany. Their ranks included immigrants to the U.S. as well as visitors stranded in the U.S. by hostilities. In many cases, the families of the internees were allowed to remain together at internment camps in the U.S. In other cases, families were separated. Limited due process was allowed for those arrested and detained.

The population of German citizens in the United States–not to mention American citizens of German birth–was far too large for a general policy of internment comparable to that used in the case of the Japanese in America.[22] Instead, German citizens were detained and evicted from coastal areas on an individual basis. The War Department considered mass expulsions from coastal areas for reasons of military security, but never executed such plans.[23]

A total of 11,507 Germans were interned during the war, accounting for 36% of the total internments under the Justice Department's Enemy Alien Control Program, but far less than the 110,000 Japanese-Americans interned.[24] Such internments began with the detention of 1,260 Germans shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor.[25] Of the 254 persons evicted from coastal areas, the majority were German.[26]

In addition, over 4,500 ethnic Germans were brought to the U.S. from Latin America and similarly detained. The Federal Bureau of Investigation drafted a list of Germans in fifteen Latin American countries whom it suspected of subversive activities and, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, demanded their eviction to the U.S. for detention.[27] The countries that responded expelled 4,058 people.[28] Some 10% to 15% were Nazi party members, including approximately a dozen who were recruiters for the NSDAP/AO, roughly the overseas arm of the Nazi party. Just eight were people suspected of espionage.[29] Also transferred were some 81 Jewish Germans who had recently fled persecution in Nazi Germany.[29] The bulk of those transferred from Latin America to the U.S. were not objects of suspicion. Many had been residents of Latin America for years, some for decades.[29] In some instances, corrupt Latin American officials took the opportunity to seize their property. Sometimes financial rewards paid by American intelligence led to someone's identification and expulsion.[29] Several countries did not participate in the program, while others operated their own detention facilities.[29][30]

The U.S. internment camps to which Germans from Latin America were directed included:[29]

- Texas

- Florida

- Oklahoma

- North Dakota

- Tennessee

Some internees were held at least as late as 1948.[31]

Review legislation

Legislation was introduced in the United States Congress in 2001 to create an independent commission to review government policies on European enemy ethnic groups during the war. On August 3, 2001, Senators Russell Feingold (D-WI) and Charles Grassley (R-IA) the European Americans and Refugees Wartime Treatment Study Act in the U.S. Senate, joined by Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) and Senator Joseph Lieberman. This bill creates an independent commission to review U.S. government policies directed against European enemy ethnic groups during World War II in the U.S. and Latin America.[32]

In 2007, the U.S. Senate passed the Wartime Treatment Study Act, which would examine the treatment of ethnic groups targeted by the U.S. government during World War II. Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions opposed it, citing historians from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum who called it exaggerated. He called it a slander on America, despite the findings that it was devastating on German and Italian-Americans livelihoods.[33]

In 2009, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, Refugees, Border Security, and International Law passed the Wartime Treatment Study Act by a vote of 9 to 1.[34]

Activism

In 2005, activists formed an organization called the German American Internee Coalition to publicize the "internment, repatriation and exchange of civilians of German ethnicity" during World War II and to seek U.S. government review and acknowledgment of civil rights violations.[35]

The TRACES Center for History and Culture based in St. Paul, Minnesota travels the United States in a "bus-eum" to educate citizens of the World War II treatment of foreign nationals in the U.S.[36]

See also

- Italian American internment

- Japanese-American internment

- German prisoners of war in the United States

- World War II related internment and expulsion of Germans in the Americas

Notes

- ^ "Italian Americans working to keep story of WWII mistreatment alive". Philadelphia Inquirer. 7 November 1999. p. C1.

- ^ New York Times: "Gregory Defines Alien Regulations," February 2, 1918, accessed April 2, 2011. The rules for subjects of Austria-Hungary were far less restrictive. New York Times: "Puts No Rigid Ban on Austrians Here," December 13, 1917, accessed April 3, 2011

- ^ Arnold Krammer, Undue Process: The Untold Story of America's German Alien Internees (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997), 14

- ^ Krammer, Undue Process, 14-5

- ^ Ann Hagedorn, Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919 (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 327-8

- ^ New York Times: "Dr. Muck Bitter at Sailing," August 22, 1919, accessed January 13, 2010

- ^ Harold Schonberg, The Great Conductors (NY: Simon and Schuster, 1967), ISBN 0671207350, 216-222

- ^ New York Times: Erich Posselt, "Muck's Last Concert in America," March 24, 1940, accessed January 13, 2010

- ^ Stanley Coben, A. Mitchell Palmer: Politician (NY: Columbia University Press, 1963), 200-1

- ^ Krammer, Undue Process, 15

- ^ New York Times: Queries from Times Readers," January 7, 1917, accessed April 1, 2011

- ^ Robert C. Doyle, The Enemy in our Hands: America's Treatment of Prisoners of War from the Revolution to the War on Terror (University Press of Kentucky, 2010), 169

- ^ New York Times: "Blow up Cormoran, Interned Gunboat," April 8, 1917, accessed March 30, 2011; Robert F. Rogers, Destiny's Landfall: A History of Guam (University of Hawaii Press, 1995), 134-40, available online, accessed April 1, 2011

- ^ The Melanesians were shipped home to New Guinea on a Japanese schooner on January 2, 1919. Hermann Hiery, The Neglected War: The German South Pacific and the Influence of World War I (University of Hawaii Press, 1995), 35, available online, accessed April 4, 2011

- ^ New York Times: "The Geier Interned until the War Ends," November 9, 1914, accessed March 30, 2011; New York Times: "Diary Bares Plots by Interned Men," December 29, 1917, accessed March 30, 2011

- ^ New York Times: "The Interned German Sailors," June 27, 1915, accessed March 30, 2011

- ^ Popular Science Monthly: "A German Village on American Soil", v. 90, January-June 1917, 424-5, accessed April 1, 2011

- ^ Great Lakes Recruit: "The German auxiliary...", vol. 4, no. 11, November 1918, accessed April 1, 2011

- ^ New York Times: "Neutral Ships Held Here," February 3, 1917, accessed March 30, 2011

- ^ New York Times: "Ten Interned Men Made their Escape," March 21, 1917, accessed March 30, 2011

- ^ New York Times: "Germans Interned at Georgia Forts," March 28, 1917, accessed March 30, 2011. More than 400 from the Wilhelm went to Fort McPherson. The others went to Fort Oglethorpe.

- ^ Tetsuden Kashima, ed., Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Part 769: Personal justice denied (University of Washington Press, 1997), ISBN, 289

- ^ Kashima, Part 769, 287–288

- ^ Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment without trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (University of Washington Press, 2003), ISBN 0295982993, 124

- ^ Franca Iacovetta, Roberto Perin, and Angelo Principe, Enemies Within: Italian and Other Internees in Canada and Abroad (University of Toronto Press, 2000), ISBN 0802082351, 281

- ^ Iacovetta, 297

- ^ Adam, 181

- ^ Thomas Adam, ed., Transatlantic Relations Series. Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Volume II (2005), ISBN 1851096280, 181

- ^ a b c d e f Adam, 182

- ^ Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico did not participate. National internment camps for citizens of Axis nations were set up in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Curaçao, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Nicaragua and Venezuela, as well as in the Panama Canal Zone.

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey, "After Stevens", The New Yorker, 43-44, March 22, 2010.

- ^ Mary Barron Stofik, Ellis Island during World War II: The Detainment and Internment of German and Italian Aliens (2007), 95

- ^ USA Today: "Senate votes to study treatment of Germans during World War II," June 9, 2007, accessed June 7, 2011

- ^ "WARTIME TREATMENT STUDY ACT", German American Internee Coalition. Accessed June 7, 2011

- ^ German American Internee Coalition: "About Us", accessed April 4, 2011

- ^ Marshall Democrat News: "Vanished: The German internment BUS-eum comes to Marshall", April 2007, accessed June 7, 2011

Sources

World War I

- Charles Burdick, The Frustrated Raider: The Story of the German Cruiser Cormoran in World War I (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979)

- Gerald H. Davis, "'Oglesdorf': A World War I Internment Camp in America," Yearbook of German-American Studies, v. 26 (1991), 249-65

- William B. Glidden, "Internment Camps in America, 1917-1920," Military Affairs, v. 37 (1979), 137-41

- Paul Halpern, A Naval History of World War I (1994)

- Arnold Krammer, Undue Process: The Untold Story of America's German Alien Internees (NY: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997), ISBN 0847685187

- Reuben A. Lewis, "How the United States Takes Care of German Prisoners," in Munsey's Magazine, v. 64 (June-September, 1918), 137ff., Google books, accessed April 2, 2011

- Jörg Nagler, "Victims of the Home Front: Enemy Aliens in the United States during World War I," in Panakos Panayi, ed., Minorities in Wartime: National and Racial Groupings in Europe, North America and Australia during the Two World Wars (1993)

- Erich Posselt, "Prisoner of War No. 3598 [Fort Oglethorpe]," in American Mercury, May-August 1927, 313-23, Google books, accessed April 2, 2011

- Paul Schmalenbach, German Raiders: A History of Auxiliary Cruisers of the German Navy, 1895-1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979)

World War II

- John Christgau, "Enemies": World War II Alien Internment (Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1985), ISBN 0595179150

- Kimberly E. Contag and James A. Grabowska, Where the Clouds Meet the Water (Inkwater Press, 2004), ISBN 1-59299-073-8. Journey of the German Ecuadorian widower, Ernst Contag, and his four children from their home in the South American Andes to Nazi Germany in 1942.

- John Joel Culley, "A Troublesome Presence: World War II Internment of German Sailors in New Mexico" in Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration v. 28 (1996), 279–295

- Heidi Gurcke Donald, We Were Not the Enemy: Remembering the United States Latin-American Civilian Internment Program of World War II (iUniverse, 2007), ISBN 0-595-39333-0

- Stephen Fox, Fear Itself: Inside the FBI Roundup of German Americans during World War II: The Past as Prologue (iUniverse, 2005), ISBN 978-0-595-35168-8

- Timothy J. Holian, The German Americans and WW II: An Ethnic Experience (NY: Peter Lang Publishing, 1996), ISBN 082044040X

- Arthur D. Jacobs, The Prison Called Hohenasperg: An American Boy Betrayed by his Government during World War II (Parkland, FL: Universal Publishers, 1999), ISBN 1-58112-832-0

- National Archives: "Brief Overview of the World War II Enemy Alien Control Program", accessed January 19, 2010

- New York Times: Jerre Mangione, "America's Other Internment," May 19, 1978, accessed January 20, 2010. Mangione was special assistant to the United States Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization from 1942 to 1948.

- PubMedCentral: Louis Fiset, "Medical Care for Interned Enemy Aliens: A Role for the US Public Health Service in World War II" in American Journal of Public Health, October, 2003, v.93(10), 1644–54, accessed January 19, 2010

- John Eric Schmitz, "Enemies Among Us: The Relocation, Internment, and Repatriation of German, Italian, and Japanese Americans during World War Two" Ph.D. Dissertation, American University 2007

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary: "Hearing on: the Treatment of Latin Americans of Japanese Descent, European Americans, and Jewish Refugees During World War II," March 19, 2009, accessed January 19, 2010

General

- Don H. Tolzmann, ed., German-Americans in the World Wars, 5 vols. (New Providence, NJ: K.G. Saur, 1995–1998), ISBN 3598215304

- vol. 1: The Anti-German Hysteria of World War One

- vol. 2: The World War One Experience

- vol. 3: Research on the German-American Experience of World War One

- vol. 4: The World War Two Experience: the Internment of German-Americans

- section 1: From Suspicion to Internment: U.S. government policy toward German-Americans, 1939–48

- section 2: Government Preparation for and implementation of the repatriation of German-Americans, 1943–1948

- section 3: German-American Camp Newspapers: Internees View of Life in Internment

- vol. 5: Germanophobia in the U.S.: The Anti-German Hysteria and Sentiment of the World Wars. Supplement and Index.

External links

- Photos of the German Village, Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia

- WORLD WAR II INTERNMENT CAMPS from the Handbook of Texas Online

- German American Internee Coalition - site includes detailed history, maps, oral accounts, and external links

- German American Internees in the United States during WWII, by Karen E. Ebel