Hyacinth (mythology)

Hyacinth /ˈhaɪəsɪnθ/ or Hyacinthus (in Greek, Ὑάκινθος, Hyakinthos) is a divine hero from Greek mythology. His cult at Amyclae, southwest of Sparta, dates from the Mycenaean era. The sanctuary (temenos) grew up around his burial mound (tumulus), located in the Classical period at the feet of Apollo's statue.[1] The literary myths serve to link him to local cults, and to identify him with Apollo.

Mythology

In Greek mythology, Hyacinth was given various parentage, providing local links, as the son of Clio and Pierus, King of Macedon, or of king Oebalus of Sparta, or of king Amyclas of Sparta,[2] progenitor of the people of Amyclae, dwellers about Sparta. His cult at Amyclae, where his tomb was located, at the feet of Apollo's statue, dates from the Mycenaean era.

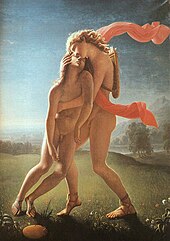

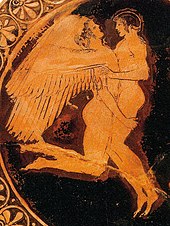

In the literary myth, Hyacinth was a beautiful youth and lover of the god Apollo, though he was also admired by West Wind, Zephyr. Apollo and Hyacinth took turns throwing the discus. Hyacinth ran to catch it to impress Apollo, was struck by the discus as it fell to the ground, and died.[3] A twist in the tale makes the wind god Zephyrus responsible for the death of Hyacinth.[4] His beauty caused a feud between Zephyrus and Apollo. Jealous that Hyacinth preferred the radiant archery god Apollo, Zephyrus blew Apollo's discus off course, so as to injure and kill Hyacinth. When he died, Apollo didn't allow Hades to claim the youth; rather, he made a flower, the hyacinth, from his spilled blood. According to Ovid's account, the tears of Apollo stained the newly formed flower's petals with the sign of his grief. The flower of the mythological Hyacinth has been identified with a number of plants other than the true hyacinth, such as the iris.[5] According to a local Spartan version of the myth, Hyacinth and his sister Polyboea were taken to heaven by Aphrodite, Athena and Artemis.[6]

Hyacinth was the tutelary deity of one of the principal Spartan festivals, the Hyacinthia, held every summer. The festival lasted three days, one day of mourning for the death of the divine hero Hyacinth, and the last two celebrating his rebirth as Apollo Hayakinthios, though the division of honours is a subject for scholarly controversy.[7]

Interpretation

The name of Hyacinth is of pre-Hellenic origin, as indicated by the suffix -nth.[8] According to classical interpretations, his myth, where Apollo is a Dorian god, is a classical metaphor of the death and rebirth of nature, much as in the myth of Adonis. It has likewise been suggested that Hyacinthus was a pre-Hellenic divinity supplanted by Apollo through the "accident" of his death, to whom he remains associated in the epithet of Apollon Hyakinthios.[9]

Apollo teaches Hyacinthus to become an accomplished adult. Indeed, according to Philostratus, Hyacinthus learns not only to throw the discus, but all the other exercises of the Palaestra as well, to shoot with a bow, music, the art of divination, and also to play the lyre. Pausanias also mentions his apotheosis, represented on the pedestal of the ritual statue of the youth at Amyclae, his place of worship. The poet Nonnus of Panopolis mentions the resurrection of the youth by Apollo. Sergent finds that the death and resurrection as well as the apotheosis, represent the transition to adult life.

See also

- Apollo et Hyacinthus, the Mozart opera

Modern sources

- Gantz, Timothy (1993). Early Greek Myth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. New York/London: Thames and Hudson.

Spoken-word myths - audio files

| The Hyacinth myth as told by story tellers |

|---|

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Homer, Iliad ii.595-600 (c. 700 BC); Various 5th century BC vase paintings; Palaephatus, On Unbelievable Tales 46. Hyacinthus (330 BC); Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.3.3; Ovid, Metamorphoses 10. 162-219 (1 AD – 8 AD); Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.1.3, 3.19.4 (160 – 176 AD); Philostratus the Elder, Images i.24 Hyacinthus (170 – 245 AD); Philostratus the Younger, Images 14. Hyacinthus (170 – 245 AD); Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods 14 (170 AD); First Vatican Mythographer, 197. Thamyris et Musae |

Notes

- ^ There have been finds of sub-Mycenaean votive figures and of votive figures from the Geometric Period, but with a gap in continuity between them at this site: "it is clear that a radical reinterpretation has taken place," Walter Burkert has observed, instancing many examples of this break in cult during the "Greek Dark Ages", including Amyklai (Burkert, Greek Religion, 1985, p 49); before the post-war archaeology, Machteld J. Mellink, (Hyakinthos, Utrecht, 1943) had argued for continuity with Minoan origins.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus 3. 10.3; Pausanias 3. 1.3, 19.4

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, 1. 3.3.

- ^ Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods; Servius, commentary on Virgil Eclogue 3. 63; Philostratus, Imagines 1. 24; Ovid Metamorphoses 10. 184.

- ^ Other divinely beloved vegetation gods who died in the flower of their youth and were vegetatively transformed, are Narkissos, Kyparissos and Adonis.

- ^ Pausanias 3. 19. 4

- ^ As Colin Edmonson points out, Edmonson, "A Graffito from Amykla", Hesperia 28.2 (April - June 1959:162-164) p. 164, giving bibliography note 9.

- ^ "As the non-Greek suffix- nth indicates, Hyakinthos was an indigenous deity at Amyklae in Laconia", remarks Nobuo Komita, "Notes on the Pre-Greek Amyklaean God Hyakinthos", 1989 (on-line text)..

- ^ Pierre Chantraine, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque, Klincksieck, 1999, article "ὑάκινθος", p. 1149 b.