Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the acquisition of the Alaska territory by the United States from the Russian Empire in the year 1867 by a treaty ratified by the Senate.

Russia, fearing a war with Britain that would allow the British to seize Alaska, wanted to sell. Russia's major role had been forcing Native Alaskans to hunt for furs, and missionary work to convert them to Christianity. The purchase, made at the initiative of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, gained the United States 586,412 square miles (1,518,800 km2) of new territory. Originally organized as the Department of Alaska, the area was successively the District of Alaska and the Alaska Territory before becoming the modern state of Alaska upon being admitted to the Union as a state in 1959.

Background

Russia was in a difficult financial position and feared losing Russian America without compensation in some future conflict, especially to the British, whom they had fought in the Crimean War (1853–1856). While Alaska attracted little interest at the time, the population of nearby British Columbia started to increase rapidly a few years after hostilities ended, with a large gold rush there prompting the creation of a British crown colony on the mainland. The Russians decided that in any future war with Britain, their hard-to-defend region might become a prime target, and would be easily captured. Therefore the Russian Emperor Alexander II decided to sell the territory. Perhaps in hopes of starting a bidding war, both the British and the Americans were approached. However, the British expressed little interest in buying Alaska. The Russians in 1859 offered to sell the territory to the United States, hoping that its presence in the region would offset the plans of Russia’s greatest regional rival, Great Britain. However, no deal was brokered due to the American Civil War.[1][2]

Also, the Russian Crown sought to repay money to its landowners after its emancipation reform of 1861 and borrowed 15 million pounds sterling from Rothschilds at 5% annually.[3] When the time came to pay back the Russian Government was short on funds. The Emperor's brother, Grand Prince Konstantin Nikolaevich offered to sell something useless.

Russia continued to see an opportunity to weaken British power by causing British Columbia, including the Royal Navy base at Esquimalt, to be surrounded or annexed by American territory.[4] Following the Union victory in the Civil War, the Tsar instructed the Russian minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl, to re-enter into negotiations with Seward in the beginning of March 1867. The negotiations concluded after an all-night session with the signing of the treaty at 4 a.m. on March 30, 1867,[5] with the purchase price set at $7.2 million, or about 2 cents per acre ($4.74/km2).[6]

American public opinion was not universally positive; to some the purchase was known as Seward's Folly. Nonetheless, most editors argued that the U.S. would probably derive great economic benefits from the purchase; friendship of Russia was important; and it would facilitate the acquisition of British Columbia.[7] Forty-five percent of newspapers endorsing the purchase cited the increased potential for annexing British Columbia in their support.[4] Historian Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer summarized the minority opinion of some American newspaper editors who opposed the purchase:[8]

Already, so it was said, we were burdened with territory we had no population to fill. The Indians within the present boundaries of the republic strained our power to govern aboriginal peoples. Could it be that we would now, with open eyes, seek to add to our difficulties by increasing the number of such peoples under our national care? The purchase price was small; the annual charges for administration, civil and military, would be yet greater, and continuing. The territory included in the proposed cession was not contiguous to the national domain. It lay away at an inconvenient and a dangerous distance. The treaty had been secretly prepared, and signed and foisted upon the country at one o'clock in the morning. It was a dark deed done in the night… The New York World said that it was a ‘sucked orange.’ It contained nothing of value but furbearing animals, and these had been hunted until they were nearly extinct. Except for the Aleutian Islands and a narrow strip of land extending along the southern coast the country would be not worth taking as a gift… Unless gold were found in the country much time would elapse before it would be blessed with Hoe printing presses, Methodist chapels and a metropolitan police. It was ‘a frozen wilderness.’

While criticized by some at the time, the financial value of the Alaska Purchase turned out to be many times greater than what the United States had paid for it. The land turned out to be rich in resources such as gold, copper, and oil.

Senate debate

When it became clear that the Senate would not debate the treaty before its adjournment on March 30, Seward persuaded President Andrew Johnson to call the Senate back into special session the next day. Many Republicans scoffed at “Seward’s folly,” although their criticism appears to have been based less on the merits of the purchase than on their hostility to Johnson and to Seward as Johnson’s political ally. Seward mounted a vigorous campaign, however, and with support from Charles Sumner, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, won approval of the treaty on April 9 by a vote of 37–2.[9] The negative votes were cast by William Pitt Fessenden of Maine and Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont.

For more than a year, as congressional relations with Johnson worsened, the House refused to appropriate the necessary funds. But in June 1868, after Johnson’s impeachment trial was over, Stoeckl and Seward revived the campaign for the Alaska purchase. The House finally approved the appropriation in July 1868, by a vote of 113–48.[10]

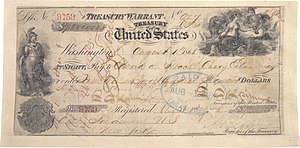

On August 1, 1868, Riggs Bank cashed the Treasury check for the Russian diplomats, closing on the American purchase.[11]

American ownership

With the purchase of Alaska negotiated by Henry Seward the United States acquired an area twice as large as Texas, but it was not until the great Klondike gold strike in 1896 that Alaska came to be seen generally as a valuable addition to American territory.

Senator Sumner had told the nation that the Russians estimated that Alaska contained about 2,500 Russians and those of mixed race, and 8,000 Indigenous people, in all about 10,000 people under the direct government of the Russian fur company, and possibly 50,000 Inuits and Alaska Natives living outside its jurisdiction. The Russians were settled at 23 trading posts, placed at accessible islands and coastal points. At smaller stations only four or five Russians were stationed to collect furs from the natives for storage and shipment when the company’s boats arrived to take it away. There were two larger towns. New Archangel, now named Sitka, had been established in 1804 to handle the valuable trade in the skins of the sea otter and in 1867 contained 116 small log cabins with 968 residents. St. Paul in the Pribilof Islands had 100 homes and 283 people and was the center of the fur seal industry.[12]

An Aleut name, “Alaska,” was chosen by the Americans. This name had earlier, in the Russian era, denoted Alaska Peninsula, which the Russians had called Alyaska (also Alyaksa is attested, especially in older sources).

Transfer ceremony

The transfer ceremony took place in Sitka on October 18, 1867. Russian and American soldiers paraded in front of the governor’s house; the Russian flag was lowered and the American flag raised amid peals of artillery.

A rather humorous description of the events was published in Finland six years later, written by a blacksmith named T. Ahllund, who had been recruited to work in Sitka only less than two years previously.[13]

We had not spent many weeks at Sitka when two large steam ships arrived there, bringing things that belonged to the American crown, and a few days later the new governor also arrived in a ship together with his soldiers. The wooden two-story mansion of the Russian governor stood on a high hill, and in front of it in the yard at the end of a tall spar flew the Russian flag with the double-headed eagle in the middle of it. Of course, this flag now had to give way to the flag of the United States, which is full of stripes and stars. On a predetermined day in the afternoon a group of soldiers came from the American ships, led by one who carried the flag. Marching solemnly, but without accompaniment, they came to the governor’s mansion, where the Russian troops were already lined up and waiting for the Americans. Now they started to pull the [Russian double-headed] eagle down, but — whatever had gone into its head — it only came down a little bit, and then entangled its claws around the spar so that it could not be pulled down any further. A Russian soldier was therefore ordered to climb up the spar and disentangle it, but it seems that the eagle cast a spell on his hands, too — for he was not able to arrive at where the flag was, but instead slipped down without it. The next one to try was not able to do any better; only the third soldier was able to bring the unwilling eagle down to the ground. While the flag was brought down, music was played and cannons were fired off from the shore; and then while the other flag was hoisted the Americans fired off their cannons from the ships equally many times. After that American soldiers replaced the Russian ones at the gates of the fence surrounding the Kolosh [i.e. Tlingit] village.

When the business with the flags was finally over, Captain of 2nd Rank Aleksei Alekseyevich Peshchurov said, “General Rousseau, by authority from His Majesty, the Emperor of Russia, I transfer to the United States the territory of Alaska.” General Lovell Rousseau accepted the territory. (Peshchurov had been sent to Sitka as commissioner of the Russian government in the transfer of Alaska.) A number of forts, blockhouses and timber buildings were handed over to the Americans. The troops occupied the barracks; General Jefferson C. Davis established his residence in the governor’s house, and most of the Russian citizens went home, leaving a few traders and priests who chose to remain.[14] [15]

Aftermath

After the transfer, a number of Russian citizens remained in Sitka, but very soon nearly all of them decided to return to Russia, which was still possible to do at the expense of the Russian-American Company. Ahllund's story “corroborates other accounts of the transfer ceremony, and the dismay felt by many of the Russians and creoles, jobless and in want, at the rowdy troops and gun-toting civilians who looked on Sitka as merely one more western frontier settlement.” Ahllund gives a vivid account of what life was like for civilians in Sitka under U.S. rule, and it helps to explain why hardly any of the Russian subjects wanted to stay there. Moreover, Ahllund’s article is the only known description of the return voyage on the Winged Arrow, a ship especially purchased in order to transport the Russians back to their native country. “The over-crowded vessel, with crewmen who got roaring drunk at every port, must have made the voyage a memorable one.” Ahllund mentions stops at the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands, Tahiti, Brazil, London, and finally Kronstadt, the port for St. Petersburg, where they arrived on August 28, 1869.[16]

Alaska Day

Alaska Day celebrates the formal transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States, which took place on October 18, 1867. The October 18, 1867 date is by the Gregorian calendar, which came into effect in Alaska the following day to replace the Julian calendar used by the Russians (the Julian calendar in the 19th century was 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar). For the selling party back in the Russia's capital city of St Petersburg, where the next day already started due to nearly 12 hours clock time difference, the handover occurred on October 7th, 1867 (not 6th) of St. Petersburg time and date under the Julian calendar.

The official celebration of the 18th October Alaska Day is held in Sitka, where schools release students early, many businesses close for the day, and events such as a parade and reenactment of the flag raising are held.

Alaska Day is also a holiday for all state workers.

See also

- A Matter of Honour, espionage novel by Jeffrey Archer in which the Alaska Purchase is a major plot element

Notes

- ^ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867". Archived from the original on 2008-04-10..

- ^ Claus-M Naske; Herman E. Slotnick (15 March 1994). Alaska: A History of the 49th State. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 330. ISBN 9780806125732.

- ^ Кто и как продавал Аляску (Who and how was sold Alaska). Russian portal.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:40491056, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=40491056instead. - ^ Seward, Frederick W., Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State. Volume: 3, 1891, p. 348.

- ^ A simple consumer price index calculation would put this at the equivalent of around $100 million dollars in 2011. see “Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount”.

- ^ Richard E. Welch, Jr., “American Public Opinion and the Purchase of Canadian America,” American Slavic and East European Review, 1958, Vol. 17 Issue 4, pp. 481–494 .

- ^ Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, A History of the United States since the Civil War (1917)1:541.

- ^ "Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, Volume 17, Page 675 (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2012-02-15..

- ^ "Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ American Artifacts: Inside the Archivist’s Office

- ^ Seward (1869).

- ^ Ahllund, T. (1873/2006).

- ^ Bancroft, H. H., (1885) pp. 590–629.

- ^ Pierce, R. (1990), p 395.

- ^ Richard Pierce, introduction to Ahllund, T., From the Memoirs of a Finnish Workman (2006).

References

- Ahllund, T., From the Memoirs of a Finnish Workman, trans. Panu Hallamaa, ed. Richard Pierce, Alaska History, 21 (Fall 2006), 1–25. (Originally published in Finnish in Suomen Kuvalehti (editor-in-chief Julius Krohn) No. 15/1873 (1 Aug) – No. 19/1873 (1 Oct)).

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe: History of Alaska: 1730–1885 (1886).

- Dunning, Wm. A. "Paying for Alaska," Political Science Quarterly Vol. 27, No. 3 (Sep., 1912), pp. 385-398 in JSTOR

- Grinëv, Andrei. V., and Richard L. Bland. “A Brief Survey of the Russian Historiography of Russian America of Recent Years,” Pacific Historical Review, May 2010, Vol. 79 Issue 2, pp. 265–278.

- Pierce, Richard: Russian America: A Biographical Dictionary, p 395. Alaska History no. 33, The Limestone Press; Kingston, Ontario & Fairbanks, Alaska, 1990.

- Holbo, Paul S (1983). Tarnished Expansion: The Alaska Scandal, the Press, and Congress 1867–1871. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press.

- Jensen, Ronald (1975). The Alaska Purchase and Russian-American Relations.

- Oberholtzer, Ellis (1917). A History of the United States since the Civil War. Vol. Vol. 1.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) online - Seward, William H. Alaska: Speech of William H. Seward at Sitka, August 12, 1869 (1869; Digitized page images & text), a primary source

External links

- Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska and related resources at the Library of Congress

- Meeting of Frontiers, Library of Congress

- [1] C-SPAN program featuring the purchase check cashed for gold at Riggs Bank.(17:00 minute mark)

- Original Document of Check to Purchase Alaska

- "Milestones: 1866-1898. Purchase of Alaska, 1867". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2011-10-19.