Cardiac surgery

| Cardiac surgery | |

|---|---|

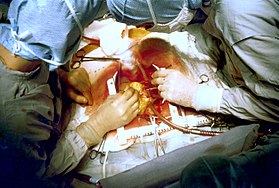

Two cardiac surgeons performing a cardiac surgery known as coronary artery bypass surgery. Note the use of a steel retractor to forcefully maintain the exposure of the patient's heart. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 35-37 |

| MeSH | D006348 |

| OPS-301 code | 5-35...5-37 |

Cardiovascular surgery is surgery on the heart or great vessels performed by cardiac surgeons. Frequently, it is done to treat complications of ischemic heart disease (for example, coronary artery bypass grafting), correct congenital heart disease, or treat valvular heart disease from various causes including endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease and atherosclerosis. It also includes heart transplantation.

Risks

The development of cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass techniques has reduced the mortality rates of these surgeries to relatively low ranks. For instance, repairs of congenital heart defects are currently estimated to have 4–6% mortality rates.[1][2] A major concern with cardiac surgery is the incidence of neurological damage. Stroke occurs in 2–3% of all people undergoing cardiac surgery, and is higher in patients at risk for stroke. [citation needed] A more subtle constellation of neurocognitive deficits attributed to cardiopulmonary bypass is known as postperfusion syndrome, sometimes called "pumphead". The symptoms of postperfusion syndrome were initially felt to be permanent,[3] but were shown to be transient with no permanent neurological impairment.[4]

Hospital readmissions often occur in cardiac surgery patients; in 2010, approximately 18.5% of patients who had a heart valve procedure in the United States were readmitted within 30 days of the initial hospitalization.[5]

In order to assess the performance of surgical units and individual surgeons, a popular risk model has been created called the EuroSCORE. This takes a number of health factors from a patient and using precalculated logistic regression coefficients attempts to give a percentage chance of survival to discharge. Within the UK this EuroSCORE was used to give a breakdown of all the centres for cardiothoracic surgeryand to give some indication of whether the units and their individuals surgeons performed within an acceptable range. The results are available on the CQC website.[6]

History

The earliest operations on the pericardium (the sac that surrounds the heart) took place in the 19th century and were performed by Francisco Romero[7], Dominique Jean Larrey, Henry Dalton and Daniel Hale Williams.[8] The first surgery on the heart itself was performed by Norwegian surgeon Axel Cappelen on the 4th of September 1895 at Rikshospitalet in Kristiania, now Oslo. He ligated a bleeding coronary artery in a 24 year old man who had been stabbed in the left axillae and was in deep shock upon arrival. Access was through a left thoracotomy. The patient awoke and seemed fine for 24 hours, but became ill with increasing temperature and he ultimately died from what the post mortem proved to be mediastinitis on the third postoperative day.[9][10] The first successful surgery of the heart, performed without any complications, was by Dr. Ludwig Rehn of Frankfurt, Germany, who repaired a stab wound to the right ventricle on September 7, 1896.[11][12]

Surgery in great vessels (aortic coarctation repair, Blalock-Taussig shunt creation, closure of patent ductus arteriosus), became common after the turn of the century and falls in the domain of cardiac surgery, but technically cannot be considered heart surgery.

Early approaches to heart malformations

In 1925 operations on the heart valves were unknown. Henry Souttar operated successfully on a young woman with mitral stenosis. He made an opening in the appendage of the left atrium and inserted a finger into this chamber in order to palpate and explore the damaged mitral valve. The patient survived for several years[13] but Souttar’s physician colleagues at that time decided the procedure was not justified and he could not continue.[14][15]

Cardiac surgery changed significantly after World War II. In 1948 four surgeons carried out successful operations for mitral stenosis resulting from rheumatic fever. Horace Smithy (1914–1948) of Charlotte, revived an operation due to Dr Dwight Harken of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital using a punch to remove a portion of the mitral valve. Charles Bailey (1910–1993) at the Hahnemann Hospital, Philadelphia, Dwight Harken in Boston and Russell Brock at Guy’s Hospital all adopted Souttar’s method. All these men started work independently of each other, within a few months. This time Souttar’s technique was widely adopted although there were modifications.[14][15]

In 1947 Thomas Holmes Sellors (1902–1987) of the Middlesex Hospital operated on a Fallot’s Tetralogy patient with pulmonary stenosis and successfully divided the stenosed pulmonary valve. In 1948, Russell Brock, probably unaware of Sellor’s work, used a specially designed dilator in three cases of pulmonary stenosis. Later in 1948 he designed a punch to resect the infundibular muscle stenosis which is often associated with Fallot’s Tetralogy. Many thousands of these “blind” operations were performed until the introduction of heart bypass made direct surgery on valves possible.[14]

Open heart surgery

Open heart surgery is a surgery in which the patient's heart is open and surgery is performed on the internal structures of the heart. It was soon discovered by Dr. Wilfred G. Bigelow of the University of Toronto that the repair of intracardiac pathologies was better done with a bloodless and motionless environment, which means that the heart should be stopped and drained of blood. The first successful intracardiac correction of a congenital heart defect using hypothermia was performed by Dr. C. Walton Lillehei and Dr. F. John Lewis at the University of Minnesota on September 2, 1952. The following year, Soviet surgeon Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Vishnevskiy conducted the first cardiac surgery under local anesthesia. During this surgery, the heart is exposed and the patient's blood is made to bypass it.

Surgeons realized the limitations of hypothermia– complex intracardiac repairs take more time and the patient needs blood flow to the body, particularly to the brain. The patient needs the function of the heart and lungs provided by an artificial method, hence the term cardiopulmonary bypass. Dr. John Heysham Gibbon at Jefferson Medical School in Philadelphia reported in 1953 the first successful use of extracorporeal circulation by means of an oxygenator, but he abandoned the method, disappointed by subsequent failures. In 1954 Dr. Lillehei realized a successful series of operations with the controlled cross-circulation technique in which the patient's mother or father was used as a 'heart-lung machine'. Dr. John W. Kirklin at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota started using a Gibbon type pump-oxygenator in a series of successful operations, and was soon followed by surgeons in various parts of the world.

Nazih Zuhdi performed the first total intentional hemodilution open heart surgery on Terry Gene Nix, age 7, on February 25, 1960, at Mercy Hospital, Oklahoma City, OK. The operation was a success; however, Nix died three years later in 1963.[16] In March, 1961, Zuhdi, Carey, and Greer, performed open heart surgery on a child, age 3½, using the total intentional hemodilution machine. In 1985 Dr. Zuhdi performed Oklahoma's first successful heart transplant on Nancy Rogers at Baptist Hospital. The transplant was successful, but Rogers, a cancer sufferer, died from an infection 54 days after surgery.[17]

Modern beating-heart surgery

Since the 1990s, surgeons have begun to perform "off-pump bypass surgery" – coronary artery bypass surgery without the aforementioned cardiopulmonary bypass. In these operations, the heart is beating during surgery, but is stabilized to provide an almost still work area in which to connect the conduit vessel that bypasses the blockage; in the U.S., most conduit vessels are harvested endoscopically, using a technique known as endoscopic vessel harvesting (EVH).

Some researchers believe that the off-pump approach results in fewer post-operative complications, such as postperfusion syndrome, and better overall results. Study results are controversial as of 2007, the surgeon's preference and hospital results still play a major role.

Minimally invasive surgery

A new form of heart surgery that has grown in popularity is robot-assisted heart surgery. This is where a machine is used to perform surgery while being controlled by the heart surgeon. The main advantage to this is the size of the incision made in the patient. Instead of an incision being at least big enough for the surgeon to put his hands inside, it does not have to be bigger than 3 small holes for the robot's much smaller hands to get through.

Pediatric cardiovascular surgery

Pediatric cardiovascular surgery is surgery of the heart of children. Russell M. Nelson performed the first successful pediatric cardiac operation at the Salt Lake General Hospital in March 1956, a total repair of tetralogy of Fallot in a four-year-old girl.[18]

References

- ^ Stark J, Gallivan S, Lovegrove J; et al. (2000). "Mortality rates after surgery for congenital heart defects in children and surgeons' performance". Lancet. 355 (9208): 1004–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90001-1. PMID 10768449.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klitzner TS, Lee M, Rodriguez S, Chang RK (2006). "Sex-related disparity in surgical mortality among pediatric patients". Congenit Heart Dis. 1 (3): 77–88. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0803.2006.00013.x. PMID 18377550.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newman M, Kirchner J, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones R, Mark D, Reves J, Blumenthal J (2001). "Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery". N Engl J Med. 344 (6): 395–402. doi:10.1056/NEJM200102083440601. PMID 11172175.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Dijk D, Jansen E, Hijman R, Nierich A, Diephuis J, Moons K, Lahpor J, Borst C, Keizer A, Nathoe H, Grobbee D, De Jaegere P, Kalkman C (2002). "Cognitive outcome after off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized trial". JAMA. 287 (11): 1405–12. doi:10.1001/jama.287.11.1405. PMID 11903027.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. Hospitals by Procedure, 2010. HCUP Statistical Brief #154. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2013.[1]

- ^ http://heartsurgery.cqc.org.uk/ CQC website for heart surgery outcomes in the UK for 3 years ending March 2009

- ^ Aris A (1997). "Francisco Romero the first heart surgeon". Ann. Thorac. Surg. 64 (3): 870–1. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00760-1. PMID 9307502.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Pioneers in Academic Surgery". U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Westaby, Stephen; Bosher, Cecil. Landmarks in Cardiac Surgery. ISBN 1-899066-54-3.

- ^ Baksaas ST, Solberg S (January 2003). "Verdens første hjerteoperasjon". Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 123 (2): 202–4.

- ^ Absolon KB, Naficy MA (2002). First successful cardiac operation in a human, 1896: a documentation: the life, the times, and the work of Ludwig Rehn (1849–1930). Rockville, MD : Kabel, 2002

- ^ Johnson SL (1970). History of Cardiac Surgery, 1896–1955. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. p. 5.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography – Henry Souttar (2004–08)

- ^ a b c Harold Ellis (2000) A History of Surgery, page 223+

- ^ a b Lawrence H Cohn (2007), Cardiac Surgery in the Adult, page 6+

- ^ Warren, Cliff, Dr. Nazih Zuhdi – His Scientific Work Made All Paths Lead to Oklahoma City, in Distinctly Oklahoma, November, 2007, p. 30–33

- ^ http://ndepth.newsok.com/zuhdi Dr. Nazih Zuhdi, the Legendary Heart Surgeon, The Oklahoman, Jan 2010

- ^ "Pediatric heart surgery" in MedlinePlus

Further reading

- Cohn, Lawrence H.; Edmunds, Jr, L. Henry, eds. (2003). Cardiac surgery in the adult. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 0-07-139129-0.

External links

- Overview at American Heart Association

- "Congenital Heart Disease Surgical Corrective Procedures", a list of surgical procedures at learningradiology.com

- What to expect before, during and after heart surgery from Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center (Seattle)

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Minimally invasive heart surgery

- Horace Gilbert Smithy, Jr., MD Papers Waring Historical Library