Dead Souls

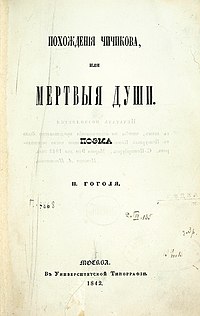

Cover page of the first edition of Dead Souls. Moscow, 1842. | |

| Author | Nikolai Gogol |

|---|---|

| Original title | Мёртвыя души, Myortvyjya dushi |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Political, Satire |

| Publication place | Russian Empire |

| Media type | Hardback and paperback |

| Followed by | Dead souls 2 (destroyed by the author before his death) |

Dead Souls ([Мёртвыя души, Myortvyjya dushi] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a novel by Nikolai Gogol, first published in 1842, and widely regarded as an exemplar of 19th-century Russian literature. The purpose of the novel was to demonstrate the flaws and faults of the Russian mentality and character. Gogol masterfully portrayed those defects through Chichikov (the main character) and people which he encountered in his endeavours. Those people are typical of then Russian middle-class. Gogol himself saw it as an "epic poem in prose", and within the book as a "novel in verse". Despite supposedly completing the trilogy's second part, Gogol destroyed it shortly before his death. Although the novel ends in mid-sentence (like Sterne's Sentimental Journey), it is usually regarded as complete in the extant form.[1]

Title

The original title, as shown on the illustration (cover page), was "The Wanderings of Chichikov, or Dead Souls. Poema", which contracted to merely "Dead Souls." In the Russian Empire, before the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, landowners were entitled to own serfs to farm their land. Serfs were for most purposes considered the property of the landowner, and could be bought, sold or mortgaged, as any other chattel. To count serfs (and people in general), the measure word "soul" was used: e.g., "six souls of serfs". The plot of the novel relies on "dead souls" (i.e., "dead serfs") which are still accounted for in property registers. On another level, the title refers to the "dead souls" of Gogol's characters, all of which visualise different aspects of poshlost ( Russian word which is rendered as "commonplace, vulgarity", moral and spiritual, with overtones of middle-class pretentiousness, fake significance and philistinism).

Background

The first part of the novel was intended to represent the Inferno of the modern-day Divine Comedy. Gogol revealed to his readers an encompassing picture of the ailing social system in Russia after the war of 1812. As in many of Gogol's short stories, the social criticism of Dead Souls is communicated primarily through absurd and hilarious satire. Unlike the short stories, however, Dead Souls was meant to offer solutions rather than simply point out problems. This grander scheme was largely unrealized at Gogol's death; the work was never completed, and it is primarily the earlier, darker part of the novel that is remembered.

In their studies of Gogol, Andrey Bely, D. S. Mirsky, Vladimir Nabokov, and other modernist critics rejected the commonly held view of Dead Souls as a reformist or satirical work. For instance, Nabokov regarded the plot of Dead Souls as unimportant and Gogol as a great writer whose works skirted the irrational and whose prose style combined superb descriptive power with a disregard for novelistic clichés. True, Chichikov displays a most extraordinary moral rot, but the whole idea of buying and selling dead souls is, to Nabokov, ridiculous on its face; therefore, the provincial setting of the novel is a most unsuitable backdrop for any of the progressive, reformist or Christian readings of the work.

Structure

The structure of the novel follows a circle, as Chichikov visits the estates of landowners living around the capital of a guberniya. Although Gogol aspired to emulate the Odyssey, many critics derive the structure of Dead Souls from the picaresque novels of the 16th and 17th centuries in that it is divided into a series of somewhat disjointed episodes, and the plot concerns a gentrified version of the rascal protagonist of the original picaresques.

Konstantin Aksakov was the first to bring out a detailed juxtaposition of Gogol's and Homer's works: "Gogol's epic revives the ancient Homeric epic; you recognize its character of importance, its artistic merits and the widest scope. When comparing one thing to another, Gogol completely loses himself in the subject, leaving for a time the occasion that gave rise to his comparison; he will talk about it, until the subject is exhausted. Every reader of The Iliad was struck by this device, too." Nabokov also pointed out the Homeric roots of the complicated absurdist technique of Gogol's comparisons and digressions.

Characters

Of all Gogol's creations, Chichikov stands out as the incarnation of poshlost. His psychological leitmotiv is complacency, and his geometrical expression roundness. He is the golden mean. The other characters — the squires Chichikov visits on his shady business — are typical "humors" (for Gogol's method of comic character drawing, with its exaggerations and geometrical simplification, is strongly reminiscent of Ben Jonson's). Sobakevich, the strong, silent, economical man, square and bearlike; Manilov, the silly sentimentalist with pursed lips; Mme Korobochka, the stupid widow; Nozdryov, the cheat and bully, with the manners of a hearty good fellow — are all types of eternal solidity. Plyushkin, the miser, stands apart, for in him Gogol sounds a note of tragedy — he is the man ruined by his "humor"; he transcends poshlost, for in the depth of his degradation he is not complacent but miserable; he has a tragic greatness. The elegiac description of Plyushkin's garden was hailed by Nabokov as the pinnacle of Gogol's art.

Plot

The story follows the exploits of Chichikov, a gentleman of middling social class and position. Chichikov arrives in a small town and quickly tries to make a good name for himself by impressing the many petty officials of the town. Despite his limited funds, he spends extravagantly on the premise that a great show of wealth and power at the start will gain him the connections he needs to live easily in the future. He also hopes to befriend the town so that he can more easily carry out his bizarre and mysterious plan to acquire "dead souls."

The government would tax the landowners on a regular basis, with the assessment based on how many serfs (or "souls") the landowner had on their records at the time of the collection. These records were determined by census, but censuses in this period were infrequent, far more so than the tax collection, so landowners would often find themselves in the position of paying taxes on serfs that were no longer living, yet were registered on the census to them, thus they were paying on "dead souls." It is these dead souls, manifested as property, that Chichikov seeks to purchase from people in the villages he visits; he merely tells the prospective sellers that he has a use for them, and that the sellers would be better off anyway, since selling them would relieve the present owners of a needless tax burden.

Although the townspeople Chichikov comes across are gross caricatures, they are not flat stereotypes by any means. Instead, each is neurotically individual, combining the official failings that Gogol typically satirizes (greed, corruption, paranoia) with a curious set of personal quirks.

Chichikov's macabre mission to acquire "dead souls" is actually just another complicated scheme to inflate his social standing (essentially a 19th-century Russian version of the ever-popular "get rich quick" scheme). He hopes to collect the legal ownership rights to dead serfs as a way of inflating his apparent wealth and power. Once he acquires enough dead souls, he will retire to a large farm and take out an enormous loan against them, finally acquiring the great wealth he desires.

Setting off for the surrounding estates, Chichikov at first assumes that the ignorant provincials will be more than eager to give their dead souls up in exchange for a token payment. The task of collecting the rights to dead people proves difficult, however, due to the persistent greed, suspicion, and general distrust of the landowners. He still manages to acquire some 400 souls, and returns to the town to have the transactions recorded legally.

Back in the town, Chichikov continues to be treated like a prince amongst the petty officials, and a celebration is thrown in honour of his purchases. Very suddenly, however, rumours flare up that the serfs he bought are all dead, and that he was planning to elope with the Governor's daughter. In the confusion that ensues, the backwardness of the irrational, gossip-hungry townspeople is most delicately conveyed. Absurd suggestions come to light, such as the possibility that Chichikov is Napoleon in disguise or the notorious and retired 'Captain Kopeikin,' who had lost an arm and a leg during a war. The now disgraced traveller is immediately ostracized from the company he had been enjoying and has no choice but to flee the town in disgrace.

In the novel's second section, Chichikov flees to another part of Russia and attempts to continue his venture. He tries to help the idle landowner Tentetnikov gain favor with General Betrishchev so that Tentetnikov may marry the general's daughter, Ulinka. To do this, Chichikov agrees to visit many of Betrishchev's relatives, beginning with Colonel Koshkaryov. From there Chichikov begins again to go from estate to estate, encountering eccentric and absurd characters all along the way. Eventually he purchases an estate from the destitute Khlobuyev but is arrested when he attempts to forge the will of Khlobuyev's rich aunt. He is pardoned thanks to the intervention of the kindly Mourazov but is forced to flee the village. The novel ends mid-sentence with the prince who arranged Chichikov's arrest giving a grand speech that rails against corruption in the Russian government.

Adaptations

Mikhail Bulgakov adapted the novel for the stage for a production at the Moscow Art Theatre. The seminal theatre practitioner Constantin Stanislavski directed the play, which opened on 28 November 1932.[2]

The extant sections of Dead Souls formed the basis for an opera in 1976 by Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin. In it Shchedrin captures the different townspeople with whom Chichikov deals in isolated musical episodes, each of which employs a different musical style to evoke the character's particular personality.

The novel was adapted for screen in 1984 by Mikhail Schweitzer as a television miniseries Dead Souls.

In 2006 the novel was dramatised for radio in two parts by the BBC and broadcast on Radio 4. It was played more for comic than satirical effect, the main comedy deriving from the performance of Mark Heap as Chichikov and from the original placing of the narrator. Michael Palin narrates the story, but is revealed actually to be following Chichikov, riding in his coach for example, or sleeping in the same bed, constantly irritating Chichikov with his running exposition.

English translations

- 1842: D.J. Hogarth (now in the public domain)

- 1936: Constance Garnett (published by The Modern Library, reissued in 2007 by Kessinger Publishing; Introduction by Clifford Odets).

- 1942: Bernard Guilbert Guerney (published by the New York Readers' Club, revised 1948).

- 1961: Andrew R MacAndrew (published by The New American Library; Foreword by Frank O'Connor).

- 1996: Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (published by Pantheon Books).

- 1998: Christopher English (published by Oxford World's Classics, reissued in 2009).

- 2004: Robert A. Maguire (published by Penguin Classics).[3]

- 2008, 2012: Donald Rayfield (published by New York Review Books).

References

- ^ Christopher English writes that "Susanne Fusso compellingly argues in her book Designing Dead Souls that Dead Souls is complete in Part One, that there was never meant to be a Part Two or Part Three, and that it is entirely consistent with Gogol's method to create the expectation of sequels, and even to break off his narrative in mid-story, or mid-sentence, and that he was only persuaded to embark on composition of the second part by the expectation of the Russian reading public" (1998, 435).

- ^ Benedetti (1999, 389).

- ^ "Dead Souls - Nikolai Gogol". Penguin Classics. 2004-07-29. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky's "A History of Russian Literature" (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky's "A History of Russian Literature" (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

- Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-52520-1.

- English, Christopher, trans. and ed. 1998. Dead Souls: A Poem. By Nikolai Gogol. Oxford World's Classics ser. Oxford: Oxford UP. ISBN 0-19-281837-6.

- Fusso, Susanne. 1993. Designing Dead Souls: Anatomy of Disorder in Gogol. Anniversary edition. Stanford: Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-2049-6.

- Kolchin, Peter. 1990. Unfree Labor: American Slavery and Russian Serfdom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

External links

- Dead Souls at Project Gutenberg — D. J. Hogarth's English translation.

- Template:Ru icon Full text of Dead Souls in the original Russian