Ussuri brown bear

| Ussuri Brown Bear Russian: Уссурийский бурый медведь Japanese: エゾヒグマ Korean: 큰곰 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ussuri brown bear (Ursus arctos lasiotus) in the Beijing Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | U. arctos

|

| Subspecies: | U. arctos lasiotus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Ursus arctos lasiotus Gray, 1867

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

baikalensis Ognev, 1924 | |

The Ussuri brown bear (Ursus arctos lasiotus), also known as the black grizzly[2] is a subspecies of the brown bear found in the Ussuri krai, Sakhalin, the Amur Oblast, northward to the Shantar Islands, Iturup Island, northeastern China, the Korean peninsula, Hokkaidō and Kunashiri Island.[3] This subspecies is thought to be the ancestor of the North American grizzly bear. Ussuri brown bears crossed to Alaska 100,000 years ago, though they did not move south until 13,000 years ago.[4] The Ainu people worshipped the Ussuri brown bear, eating its flesh and drinking its blood as part of a religious festival known as iomante.[5]

Appearance

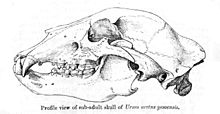

It is very similar to the Kamchatka brown bear, though it has a more elongated skull, a less elevated forehead, somewhat longer nasal bones and less separated zygomatic arches, and is somewhat darker in color, with some individuals being completely black, a fact which once led to the now refuted speculation that black individuals were hybrids of brown bears and Asian black bears. Adult males have skulls measuring 38.7 cm long and 23.5 cm wide. They can occasionally reach greater sizes than their Kamchatka counterparts: the largest skull measured by Sergej Ognew (1931) was only slightly smaller than that of the largest Alaskan bear on record at the time.[3]

Behaviour and biology

Dietary habits

In Sikhote Alin, Ussuri brown bears den mostly in burrows excavated into hillsides, though they will on rarer occasions den in rock outcroppings or build ground nests. These brown bears rarely encounter Asian black bears, as they den at higher elevations and on steeper slopes than the latter species. They may on rare occasions attack their smaller black cousins.[6]

In middle Sakhalin in spring, brown bears feed on the previous year's red bilberry, ants and flotsam, and at the end of the season, they concentrate on the shoots and rhizomes of tall grasses. On the southern part of the island, they feed primarily on flotsam, as well as insects and maple twigs. In springtime in Sikhote Alin, they feed on acorns, Manchurian walnuts and Korean nut pine seeds. In times of scarcity, in addition to bilberries and nuts, they capture larvae, wood-boring ants and lily roots. In early summer, they will strip bark from white-barked fir trees and feed on their cambium and sap. They will also eat berries from honeysuckle, yew, Amur grapevine and buckthorn. In southern Sakhalin, their summer diet consists of currents and chokeberries are eaten. In the August period in the middle part of the island, fish comprise 28% of their diet.[3]

In Hokkaido, the brown bear has a diet including small and large mammals, fish, birds and insects such as ants.[7]

Interactions with tigers

Ussuri brown bears are occasionally preyed on by Siberian tigers, and are estimated by one source to make up 1.0-1.5% of their diet;[8] however, another source states that such attacks are rare and do not have any actual significance because Siberian tigers are almost extinct.[9] Siberian tigers most typically attack brown bears in the winter, in the hibernaculum.[10] They are typically attacked by tigers more often than the smaller black bears, due to their habit of living in more open areas and their inability to climb trees. When hunting bears, tigers will position themselves from the leeward side of a rock or fallen tree, waiting for the bear to pass by. When the bear passes, the tiger will spring from an overhead position and grab the bear from under the chin with one forepaw and the throat with the other. The immobilised bear is then killed with a bite to the spinal column. After killing a bear, the tiger will concentrate its feeding on the bear's fat deposits, such as the back, legs and groin.[11] Tiger attacks on bears tend to occur when ungulate populations decrease. While tigers can successfully hunt bears, there are also records of brown bears killing tigers (including adult tigers, and tigers whose age and sex were not specified),[12] either in disputes over prey, or in self defense or for consumption.[11][13][14] There have been observations of bears that changed their path after coming across tiger trails, and of bears following tiger tracks with no signs of fear and sleeping in the same den.[11][15] However, despite the possibility of tiger predation, some large brown bears may actually benefit from the tiger's presence by appropriating tiger kills that the bears may not be able to successfully hunt themselves, as they sometimes can dominate these disputes over kills.[16] Indeed, Russian researchers have identified specific "satellite bears" who regularly "follow tigers over extensive periods of time, sequentially usurping kills" by tracking the tigers in the spring snow.[17]

Range and status

About 500–1,500 Ussuri brown bears are present in Heilongjiang, and are classed as a vulnerable species. Illegal hunting and capture has become a very serious contributing factor to the decline in bear numbers, as their body parts are of high economic value.[18]

Five regional sub-populations of Ussuri brown bears are now recognized in Hokkaido. Of these, the small size and isolation of the western Ishikari subpopulation has warranted its listing as an endangered species in Japan’s Red Data Book. 90 to 152 brown bears are thought to dwell in the West Ishikari Region and from 84 to 135 in the Teshio-Mashike mountains. Their habitat has been severely limited by human activities, especially forestry practices and road construction. Excessive harvesting is also a major factor in limiting their population.[18]

In Russia, the Ussuri brown bear is considered a game animal, though it is not as extensively hunted as the Eurasian brown bear.[18]

In Korea, a few of this bears still exist only in the North, where this bears are officially recognized as natural monument by its government. Traditionally called Ku'n Gom(big bear), whereas black bears are called Gom(bear), the Ussuri brown bear went extinct many years ago in South Korea largely due to poaching. In North Korea, there are two major areas of brown bear population: including JaGang province and HamKyo'ng Mountains. The ones from JaGang province are called RyongLim Ku'n Gom(RyongLim big bear) and they are listed as Natural Monument No.124 of North Korea.[19] The others from Hamkyo'ng Mountains are called GwanMoBong Ku'n Gom(GwanMo Peak big bear) and they are listed as Natural Monument No.330 of North Korea.[20] All big bears(Ussuri brown bears) in North Korea are mostly found around the peak areas of mountains. Their average size varies from 150 kg to 250 kg for Ryonglim bears found in the area south of Injeba'k Mountain, up to average of 500 kg to 600 kg for the ones found in the area north of Injeba'k Mountain.[19]

Attacks on humans

In Hokkaido, during the first 57 years of the 20th century, 141 people died from bear attacks, and another 300 were injured.[21] The Sankebetsu brown bear incident (三毛別羆事件, Sankebetsu Higuma jiken), which occurred in December 1915 at Sankei in the Sankebetsu district was the worst bear attack in Japanese history, and resulted in the deaths of seven people and the injuring of three others.[22] The perpetrator was a 380 kg and 2.7 m tall brown bear, which twice attacked the village of Tomamae, returning to the area the night after its first attack during the prefuneral vigil for the earlier victims. The incident is frequently referred to in modern Japanese bear incidents, and is believed to be responsible for the Japanese perception of bears as man-eaters.[21]

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2008

- ^ California Grizzly by Tracy Irwin Storer, Lloyd Pacheco Tevis. Publisher University of California Press, 1996 ISBN 0-520-20520-0

- ^ a b c Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), V.G Heptner and N.P Naumov editors, Science Publishers, Inc. USA. 1998. ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ^ A REVIEW OF BEAR EVOLUTION BRUCEM CLELLANF,o rest Sciences Research Branch,R evelstoke Forest District,R PO#3, Box 9158, Revelstoke, BC VOE3 KO DAVIDC . REINERU, .S. Fish and WildlifeS ervice, NS 312, Universityo f Montana, Missoula, MT

- ^ "The Golden Bough - A Study in Magic and Religion" (1922) by Sir James George Frazer

- ^ Denning ecology of brown bears and Asiatic black bears in the Russian Far East

- ^ Onoyama, Keiichi (1987-11-16). "Ants as prey of the Yezo brown bear Ursus arctos yesoensis with consideration on its feeding habits" (PDF). Res. Bull. Obihiro University. 15. Obihiro, Hokkaidō, Japan: Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine: 313–318. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Seryodkin, Ivan (2006). "The ecology, behavior, management and conservation status of brown bears in Sikhote-Alin (in Russian)". Far Eastern National University, Vladivostok, Russia. pp. 1–252.

- ^ V.G. Heptner and N.P. Naumov. Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol 2 IIa 1998. New Delhi, India: Amerind Publishing. p670-1

- ^ V.G. Heptner and N.P. Naumov. Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol 2 IIa 1998. New Delhi, India: Amerind Publishing. p671

- ^ a b c V.G Heptner & A.A. Sludskii. Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2. pp. 175–177. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- ^ Mammals of the Soviet Union Volume 2, by V.G Heptner & A.A. Sludskii, p177

- ^ Seryodkin, I. V., J. M. Goodrich, A. V. Kostyrya, B. O. Schleyer, E. N. Smirnov, L. L. Kerley, and D. G. Miquelle. 2005. Relationship between tigers, brown bears, and Himalayan black bears. Pages 156-163 in D. G. Miquelle, E. N. Smirnov, and J. M. Goodrich (eds.), Tigers of Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik: Ecology and Conservation. Vladivostok, Russia: PSP.

- ^ [Table 1. Location, physical status, size and circumstances of deaths of Amur tiger males in the Russian Far East, 1970-1994. http://tigers.ru/articles/tab_eng.html#tab1]

- ^ Anatoliy Grigorievitch Yudakov and Igor Georgievitch Nikolaev (2004). "Hunting Behavior and Success of the Tigers' Hunts". The Ecology of the Amur Tiger based on Long-Term Winter Observations in 1970-1973 in the Western Sector of the Central Sikhote-Alin Mountains (english translation ed.). Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far-Eastern Scientific Center, Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

- ^ Miquelle, D.G., Smirnov, E.N., Goodrich, J.M. (2005). "1". Tigers of Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik: ecology and conservation. Vladivostok, Russia: PSP.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kerley, Linda; Goodrich, John, and Miquelle, Dale. "Bears and tigers in the Far East" International Bear News. 5 (2): p4

- ^ a b c Brown Bear Conservation Action Plan for Asia

- ^ a b North Korean Human Geography, Ryonglim Big Bear Cite error: The named reference "korea ryonglim" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ North Korean Human Geography, Gwanmobong Big Bear

- ^ a b Knight, John (2000). Natural Enemies: People-Wildlife conflicts in Anthropological Perspective. p. 254. ISBN 0-415-22441-1.

- ^ "Fu Watto Tomamae". Retrieved 2008-06-07.