The Tower House

- For the house of the same name in Leicestershire, see The Tower House, Lubenham.

| The Tower House | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Holland Park, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, West London, England |

| Built | 1875–81 |

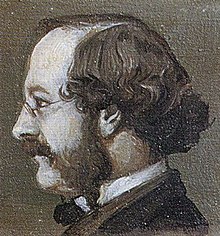

| Architect | William Burges |

| Architectural style(s) | Gothic Revival |

| Governing body | Privately owned |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | The Tower House |

| Designated | 29 July 1949[1] |

| Reference no. | 1225632 |

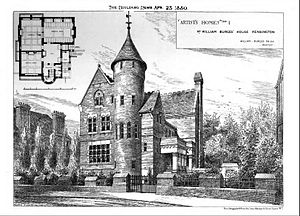

The Tower House at 29 Melbury Road (originally 9 Melbury Road) is a late Victorian townhouse in London's Holland Park district of Kensington and Chelsea built for himself between 1875-81 by the architect and designer William Burges. Designed in the French Gothic Revival style, it was designated a Grade I listed building on 29 July 1949.

Burges purchased the plot of land in 1875, and the house was largely complete by 1878, with construction undertaken by the Ashby Brothers, and interior decoration by the likes of sculptor Thomas Nicholls and artist Henry Stacy Marks. Decoration of the house, together with the designing of innumerable items of furniture and metalwork, continued until Burges's early death in 1881. The house was inherited by his brother in law, Richard Popplewell Pullan, who completed some of Burges's unfinished projects. It was then bought by Colonel T. H. Minshall, the father of Merlin Minshall, and later sold to Colonel E.R.B. Graham in 1933. The poet John Betjeman acquired the property in 1962. Following a period of neglect and decay, it underwent restoration under the ownership, firstly, of the actor Richard Harris and, latterly, of the guitarist Jimmy Page.

Burges described the house as a "model residence of the thirteenth century". The architectural scholar, and authority on Burges, J. Mordaunt Crook, considered the house to be "the most complete example of a medieval secular interior produced by the Gothic Revival and the last" and the "synthesis of [Burges's] career and a glittering tribute to his achievement."[2][3] The exterior and the interior of the Tower House echo elements of Burges's earlier work, including the McConnochie House, Castell Coch and Cardiff Castle. The house is built in red brick, with Bath stone dressings and green slates from Cumberland, with a distinctive cylindrical tower and conical roof, influenced by Castell Coch. The ground floor contains a drawing room, a dining room and a library, while the first floor has two bedroom suites and an armoury.

The Tower House retains much of its internal structural decoration, but much of the furniture and most of the fittings and contents that Burges designed have been dispersed. Many, including the Great Bookcase, the Zodiac settle, The Golden Bed and the Red Bed, now form part of museum collections, including those of the The Higgins Art Gallery & Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Others are held in private collections.

Location

The Tower House house is situated on a corner of Melbury Road opposite Stavordvale Lodge and next to Woodland House, built for the artist Luke Fildes.[4] It lies 0.3 miles (0.48 km) due northeast of Kensington (Olympia) station and 0.8 miles (1.3 km) southeast of Shepherd's Bush, approached by Holland Road (A3220) and Addison Crescent and Road, which lead into Melbury Road.[5] To the south, Melbury Road links directly to Kensington High Street, which is about 100 metres (330 ft) away.

The development of Melbury Road in the grounds of Little Holland House created an art colony in Holland Park, the inhabitants of which became known as the Holland Park Circle.[6] The artist Frederic, Lord Leighton, whose Leighton House (at 12 Holland Park Road), begun in 1866, combined medieval and Moorish elements in a style resembling that of William Burges.

History

Construction and craftsmanship

From 1875, although he continued to work on finalising several other projects, Burges received no further major commissions. The construction, decoration and furnishing of the Tower House occupied much of the last six years of his life, designed with his "experience of twenty years learning, travelling and building".[7] Initial drawings for the Tower House were made in July 1875, with the present form of the house decided upon by the end of the year.[8] Burges rejected plots in Victoria Road, Kensington and Bayswater before finding the plot on Melbury Road.[9] He agreed to purchase the land from the Earl of Ilchester, the owner of the Holland Estate, in December 1875. The ground rent was £100 per annum. Building began the following year, contracted to the Ashby Brothers of Kingsland Road. A basic cost of £6,000 was agreed (£Format price error: cannot parse value "Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2023) in index "UK"." as of 2024).[10][11]

Burges used many artists and craftsmen in the interior decoration of the Tower House, which remained unfinished at his death.[8] An estimate book compiled by Burges is held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, and contains the names of the individuals and firms who undertook work at the house.[8] Many of the craftsmen who worked on the Tower House had previously worked with Burges on other projects.[8] Sculptor Thomas Nicholls undertook the stone carving for the house, including the stone capitals and corbels and the chimneypieces. The mosaic and marble work was contracted to Burke and Company of Regent Street, while the decorative tiles were supplied by Simpson and Sons of the Strand.[8] John Ayres Hatfield crafted the bronze decorations on the doors, while the woodwork was the responsibility of John Walden of Covent Garden.[8]

Burges used the artists Henry Stacy Marks and Fred Weeks to undertake mural paintings at the Tower House. Decorators Campbell and Smith of Southampton Row were responsible for the majority of the painted decorations. They were later hired by Richard Harris in his restoration of the Tower House.[8] Marks painted birds above the 'Alphabet' frieze in the library, and Weeks painted legendary lovers in the drawing-room. The pair also painted the figures on the bookcases.[12] The stained glass was by Saunders and Company of Long Acre, with initial designs by Horatio Walter Lonsdale.[8]

Burges and after

Burges spent his first night at the Tower House on the 5 March 1878, and died in his bedroom there on 20 April 1881. He was 53 years old.[13] He had caught a chill while overseeing work at Cardiff Castle and returned to the Tower House, half paralysed, where he lay dying for some three weeks.[14] Among his last visitors were Oscar Wilde and James Whistler.[14] Burges was buried at the cemetery at West Norwood in the tomb that he had designed for his mother.[14]

The house was inherited by Burges's brother in law, Richard Popplewell Pullan, who completed some of his unfinished projects and wrote two studies of his work. It was then purchased by Colonel T. H. Minshall, father of Merlin Minshall and author of What to Do with Germany and Future Germany.[15] Minshall sold his lease on the house to Colonel E.R.B. Graham in 1933.

John Betjeman

The poet John Betjeman, a champion of Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, was a friend of the Grahams and was given the remaining two-year lease on the Tower House, together with some of the furniture, on Mrs Graham's death in 1962.[16] Betjeman discovered the Narcissus washstand, made by Burges for his rooms in Buckingham Street and subsequently moved to the Tower House, in a shop in Lincoln.[17] He gave the washstand to the Evelyn Waugh, a fellow enthusiast for Victorian art and architecture, who made it the centrepiece of his 1957 novel, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold.[18] Betjeman subsequently gave both the Zodiac settle, and the Philosophy cabinet to Waugh, supposedly to appease Betjeman's wife Penelope, who failed to share their appreciation of Gothic Revival painted furniture.[17] In 1957, the Tower House featured in the fifth episode of Betjeman's BBC television series, An Englishman's Castle.[19]

Betjeman considered that the house would be too costly to run permanently, with potential liability for £10,000 of renovations upon the expiration of the lease.[16] The Tower House was unoccupied between 1962 and 1966, during which time it was vandalised. With the aid of grants from the Ministry of Housing and Local Government and Greater London Council, restoration of the house began in 1966.[8]

1970s to present

Richard Harris paid £75,000 for the Tower House in 1970 (£Format price error: cannot parse value "Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2023) in index "UK"." as of 2024),[10] after discovering that the American entertainer Liberace had made an offer to buy the house but had not put down a deposit.[20] After reading of the intended sale in the Evening Standard, he purchased the property outright the following day,[20] describing his purchase as the "biggest gift I've ever given myself".[20] In his autobiography the British entertainer Danny La Rue recalled a visit to the Tower House with Liberace, writing that "... It was a strange building and had eerie murals painted on the ceiling ... I was very uncomfortable and sensed evil".[21] La Rue later met Harris who told him that he had bought children's toys for the "little bastards" inhabiting the Tower House, who then left Harris alone.[21]

Harris employed the original decorators, Campbell Smith & Company Ltd., to carry out restoration work on the interior,[22] using Burges's original drawings from the Victoria and Albert Museum,[20] commenting that he "wanted Burges to be proud of us".[23]

The Led Zepellin guitarist Jimmy Page bought the house from Harris in 1972 for £350,000 (£Format price error: cannot parse value "Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2023) in index "UK"." as of 2024)[10],[24] outbidding David Bowie.[25] Page, an enthusiast for Burges and for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, commented in an interview in 2012: "I was still finding things 20 years after being there - a little beetle on the wall or something like that, it's Burges's attention to detail that is so fascinating."[26] The house is not open to the public.

Architecture

Exterior and design

In contrast to the typical style of houses on the Holland Estate, the Tower House was to be a "pledge to the spirit of gothic in an area given over to Queen Anne".[27] Burges despised the Queen Anne style, writing that it: "like other fashions ... will have its day, I do not call it Queen Anne art, for, unfortunately I see no art in it at all".[28] Burges's inspiration was French Gothic domestic architecture of the thirteenth century,[8] and more recent models provided by the work of the nineteenth century French revivalist architect Viollet-le-Duc.[8] Burges's neighbour Luke Fildes would describe the Tower House as a "model modern house of moderately large size in the 13th-century style built to show what may be done for 19th-century everyday wants".[27]

The house has an L-shaped plan, and the exterior is plain, of red brick, with Bath stone dressings and green slates from Cumberland.[11] The house is not large, its floor-plan being little more than 50 feet (15 m) square,[29] but the approach Burges took to its construction was on a grand scale, with floor depths being sufficient to support rooms four or five times their size. The architect R. Norman Shaw considered the concrete foundations to be suitable "for a fortress".[30] This approach, combined with Burges's architectural skills and the minimum of exterior decoration, created a building that Crook describes as "simple and massive".[29] As was usual with Burges, many elements of earlier designs were adapted and included. The street frontage comes from the other townhouse Burges designed, the McConnochie House in Cardiff, for Lord Bute's engineer. The cylindrical tower and conical roof derive from Castell Coch and the interiors are drawn from examples at Cardiff Castle.[28][29]

At the Tower House the stair is consigned to the conical tower, Burges avoiding the error that he had made at the McConnochie House when he placed the large staircase in the middle of the hall.[29] Above a basement, the two storeys of the house are surmounted by a roof garret.[8] The ground floor contains a drawing room, a dining room and a library, while the first floor holds two bedroom suites and a study. The Tower House was designated a Grade I listed building on 29 July 1949.[1]

Interior

"The sturdy exterior gives little hint of the fantasy (Burges) created inside."[31] Each room has a complex iconographic scheme of decoration: in the hall is Time, in the drawing room, Love, in Burges' bedroom, the Sea. Massive fireplaces with elaborate overmantels were carved and installed in the library,[32] and depictions of mermaids and sea-monsters of the deep were placed in his own bedroom.[33] Crook describes them as "veritable altars of art..some of the most amazing pieces of decoration Burges ever designed".[34]

Ground floor

A bronze-covered door with relief panels depicting figures, opens onto the entrance hall.[8] At the time of Burges's death, the letterbox, in the form of the messenger Mercury wearing a tunic powdered with letters, was near the front door.[35] The letterbox is now lost, but a contemporary copy is in the collection of The Higgins Art Gallery & Museum.[36] The interior centres on the double-height entrance hall, its painted ceiling depicting the astrological signs of the constellations, arranged in the positions they held when the house was first occupied.[8] A mosaic floor in the entrance hall is designed as a labyrinth, the centre depicting the myth of Theseus slaying the Minotaur. The bronze-covered door to the garden entrance is decorated with a relief of the Madonna and child.[8] Emblems adorn the five doors on the ground floor of the Tower House, each one relevant to their respective rooms.[35] A flower marks the door to the garden, with the front door marked by a key. The library is indicated by an open book, the drawing or music room by instruments, and the dining room by a bowl and flask of wine.[37]

- Library

The library featured a sculptured mantlepiece resembling the Tower of Babel, with walls lined with bookcases.[38] In the ceiling are depicted the founders of "systems of theology and law". An illuminated alphabet of architecture and the visual arts completes the scheme, with the letters of the alphabet incorporated, including a dropped letter 'H' falling below the cornice.[34] Artists and craftsmen are featured at work on each lettered door of the bookcases that surround the room.[8] Both the 'Architecture Cabinet' and the 'Great Bookcase' stood in this room.[34]

- Drawing room

On wall opposite to the library fireplace, an opening leads into the drawing room. The room's decorative scheme is "the tender passion of Love".[8] The ceiling is painted with medieval cupids, and the walls are covered with mythical lovers.[38] Carved figures from the Roman de la Rose decorate the chimneypiece,[8] which Crook considered "one of the most glorious that Burges and Nicholls ever produced."[32] Echoing Crook, Charles Handley-Read, the first scholar of the twentieth century to give Burges serious consideration, wrote: "Working together, Burges and Nicholls had transposed a poem into sculpture with a delicacy that is very nearly musical. The Roman de la Rose has come to life."[39] Three stained glass windows are set in ornamented marble linings.[8] Opposite the windows, Burges placed the 'Zodiac settle', originally designed for Buckingham Street.

- Dining room

The dining room is devoted to Geoffrey Chaucer's The House of Fame. Above the marble fireplace sits the Goddess of Fame.[40] The tiles depict fairy stories, "tall stories (being) part of the dining room rite",[40] including Reynard the Fox, Jack and the Beanstalk and Little Red Riding Hood. To mask cooking smells, the walls of the dining room are covered with Devonshire marble, surmounted by glazed picture tiles.[35] Burges designed most of the cutlery and plate used in this room, which display his skills as a designer of metalwork, including the claret jug and Cat Cup chosen by Lord and Lady Bute as mementos from Burges's collection after his death.[41]

First floor

The windows of the stair turret approaching the first floor represent "the Storming of the Castle of Love".[8] On the first floor are two main bedrooms and an armoury. "The Earth and its productions" is the theme of the guest room facing the street.[8] Its ceiling is adorned with butterflies and fleur-de-lis, and at the crossing of the main beams is a convex mirror in a gilded surround. Along the length of the beams are paintings of frogs and mice. A frieze of flowers once in the room was painted over, and has since been restored.[8] The Golden Bed and the Vita Nuova washstand designed by Burges for this room are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[42][43]

Burges's bedroom overlooks the garden, with the theme of sea creatures.[8] Its elaborate ceiling is segmented into panels by gilded and painted beams, studded with miniature convex mirrors set within gilt stars. Fish and eels swim in a deep frieze of waves painted under the ceiling, and fish are also carved in relief on the chimneypiece. On the fire-hood, a sculpted mermaid is gazing into a looking-glass, with seashells, coral, seaweed and a baby mermaid also represented.[8] In this room, Burges placed two of his most personal pieces of furniture, the Red Bed (his own), and the Narcissus Washstand, both of which originally came from Buckingham Street.[44] The bed is painted blood red and features a panel depicting Sleeping Beauty. The washstand is red and gold, its tip-up basin of marble inlaid with fishes in silver and gold.[45]

"The most complete example of a medieval secular interior produced by the Gothic Revival, and the last."

—Crook writing on the Tower House.[2]

The final room on the first floor was designated an armoury by Burges, in which he displayed his large collection of armour. The collection was bequeathed to the British Museum upon his death.[46] A carved chimneypiece in the armoury has three roundels carved with the goddesses Minerva, Venus and Juno in medieval attire.[8]

The garret of the Tower House originally contained day and night nurseries, although quite why the unmarried and childless Burges thought them necessary is uncertain. They contain a pair of decorated chimneypieces featuring the tale of Jack and the Beanstalk and three monkeys at play.[8]

Garden

The garden at the back of the Tower House featured raised flowerbeds "planned according to those pleasances depicted in mediaeval romances; beds of scarlet tulips, bordered with stone fencing".[11] Burges and friends would take tea in the garden, lounging on "marble seats or on Persian rugs and embroidered cushions round the pearl-inlaid table, brilliant with tea service composed of things precious, rare and quaint".[11] A mosaic terrace is surrounded by marble seats, with a marble statue of a boy with a hawk at its centre, sculpted by Thomas Nicholls.[9] The gardens of the Tower House and the adjacent Woodland House both contain trees from the former Little Holland House.[27]

Furniture

In designing the medieval interior to the house, Burges illustrated his skill as a jeweller, metalworker and designer[47] and produced some of his best furniture pieces including the Zodiac settle, the Dog Cabinet and the Great Bookcase, the last of which Charles Handley-Read described as "occupying a unique position in the history of Victorian painted furniture".[48] The fittings were as elaborate as the furniture: the tap for one of the guest washstands was in the form of a bronze bull from whose throat water poured into a sink inlaid with silver fish.[49] Within the Tower House Burges placed some of his finest metalwork; the artist Henry Stacy Marks wrote "he could design a chalice as well as a cathedral ... His decanters, cups, jugs, forks and spoons were designed with an equal ability to that with which he would design a castle."[50]

Much of Burges's early furniture, such as the Narcissus Washstand, was originally made for his office at Buckingham Street and was subsequently moved to the Tower House.[17] Other examples include the Great Bookcase and the Zodiac settle. The Great Bookcase was also part of Burges's contribution to the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition.[51] Later pieces, such as the Crocker Dressing Table and the Golden Bed and its accompanying Vita Nuova washstand, were specifically made for suites of rooms at the Tower House.[52]

Many of the decorative items designed by Burges for the Tower House were dispersed following his death. Several pieces from the collection of Charles Handley-Read, who was instrumental in reviving interest in Burges, were acquired by The Higgins Art Gallery & Museum, Bedford. The Zodiac settle was acquired by the Higgins in 2011.

Dispersed furniture and locations

This is a table of known pieces of furniture originally in situ in the Tower House, with their dates of construction and their current location, where known.

| Original room | Piece, date and location |

|---|---|

| Entrance hall |

|

| Library |

|

| Drawing room |

|

| Dining Room |

|

| Burges' bedroom |

|

| Guest bedroom |

|

| Armoury |

|

| Day nursery |

|

| Unknown room |

|

Scholarship

The house was extensively described by Burges' brother-in-law, Richard Popplewell Pullan in the first of two works he wrote about Burges, The House of W. Burges, A.R.A., published in 1886. As with Burges, the house was then largely ignored, until Mordaunt Crook's centenary volume, William Burges and the High Victorian Dream, published in 1981, in which Crook wrote at length of both the building and its contents. More recent coverage was given in London 3: North West, the revision to the Buildings of England guide to London written by Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry, and published in 1991. The house is also referenced in Matthew Williams's William Burges,[54] published 2007 and in Great Houses of London by James Stourton and photographer Fritz von der Schulenburg,[55] published in 2012, which also includes some recent photographs. Pullan's photographs of the Tower House from 1885 were included in Panoramas of Lost London, by Philip Davies,[56] published in 2011.

Notes

- ^ a b "The Tower House". English Heritage list. English Heritage. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ a b Crook 1981, p. 327

- ^ Crook 1981b, p. 58

- ^ Weinreb, Kay & Kay 2011, p. 539

- ^ "The Tower House" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Dakers 1999, p. 4

- ^ Crook 1982, p. 58

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Survey of London: volume 37: Northern Kensington". British History Online. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ a b Dakers 1999, p. 175

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Dakers 1999, p. 176

- ^ Willsdon 2000, p. 316

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 17

- ^ a b c Crook 1981, p. 328.

- ^ U K Stationery Office 2011, p. 26

- ^ a b Wilson 2011, p. 208

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Case 4: (2010–2011) A Zodiac settle designed by William Burges" (PDF). Arts Council. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Crook 1981b, p. 77.

- ^ Betjeman 2010, p. 62

- ^ a b c d Callan 1990, p. 138

- ^ a b La Rue 1997, p. 137

- ^ Dakers 1999, p. 276

- ^ Callan 2004, p. 200

- ^ Callan 1990, p. 157

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 410

- ^ "Rock legend's pilgrimage to castle". BBC News Online. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ a b c Dakers 1999, p. 173

- ^ a b Dakers 1999, p. 174

- ^ a b c d Crook 1981, p. 308

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 309

- ^ Cherry & Pevsner 2002, p. 511.

- ^ a b Crook 1981, p. 317

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 325

- ^ a b c Crook 1981, p. 319

- ^ a b c Dakers 1999, p. 177

- ^ "Letterbox". The Higgins Art Gallery & Museum. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 310

- ^ a b Dakers 1999, p. 178

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 318

- ^ a b Crook 1981, p. 311

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 315

- ^ a b "Burges Washstand". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ a b "The Golden Bed". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 326

- ^ Crook 1981, pp. 326–7

- ^ "British Museum: William Burges". British Museum. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 312

- ^ Handley-Read, Charles (November 1963). The Burlington Magazine. Vol. 105, no. 728. p. 504.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Osband, p. 112

- ^ Crook 1981, p. 316

- ^ Crook 1981b, p. 72.

- ^ Crook 1981b, pp. 84–85.

- ^ "Zodiac Settle by William Burges". Art Fund. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Williams 2010, pp. 16–17

- ^ Stourton 2012, pp. 220–228

- ^ Davies 2011, pp. 136–142

References

- Betjeman, John (2010). Murray Betjeman's England. ISBN 978-1-84854-380-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Callan, Michael Feeney (1990). Richard Harris: A Sporting Life. London: Sidgwick & Jackson Limited. ISBN 978-0-283-99913-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Callan, Michael Feeney (2004). Square Richard Harris: Sex, Death & The Movies. ISBN 978-1-86105-766-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crook, J. Mordaunt (1981). William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3822-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crook, J. Mordaunt (1982). The Strange Genius of William Burges. London: National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0-7200-0259-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cherry, Bridgett; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002) [1991]. The Buildings of England: London 3 North West. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09652-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dakers, Caroline (1999). The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08164-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Philip (2011). Panoramas of Lost London. English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-907176-72-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - La Rue, Danny (1987). Drags to Riches: My Autobiography. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-009862-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Minshall, Merlin (1977). Guilt Edged. London: Panther.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stourton, James (2012). Great Houses of London. Francis Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3366-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Her Majesty's Stationery Office (2011). Export of Objects of Cultural Interest 2010/11: 1 May 2010 – 30 April 2011. The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-10-851100-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weinreb, Christopher Hibbert Ben; Kay, Julia; Kay, John (2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, Matthew (2007). William Burges. London: Pitkin Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84165-139-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Willsdon, Clare A.P. (2000). Mural Painting in Britain, 1840–1940: Image and Meaning. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-817515-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, A.N. (2011). Betjeman. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-9305-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 1880s photographs of the exterior and interior of The Tower House from the Royal Institute of British Architects

- Elevation and sections of The Tower House from the Survey of London

- Floorplans of The Tower House from the Survey of London

- A photo comparison of Tower House and the St. Anthony Hall chapter house of Trinity College, Connecticut

- The Arts & Crafts Home website - Colour photographs of The Tower House