User:Banjosarebomb/sandbox

Chemical and biological properties

[edit]

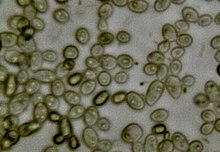

The kombucha culture is a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), comprising Acetobacter (a genus of acetic acid bacteria) and one or more yeasts. These form a zoogleal mat. In Chinese, this microbial culture is called haomo in Cantonese, or jiaomu in Mandarin, (Chinese: 酵母; lit. 'yeast mother'). It is also known as Manchurian Mushroom.

A kombucha culture may contain one or more of the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Candida stellata, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Torulaspora delbrueckii, and Zygosaccharomyces bailii. Alcohol production by the yeast(s) contributes to the production of acetic acid by the bacteria.

Although the bacterial component of a kombucha culture comprises several species, it almost always includes Gluconacetobacter xylinus (formerly Acetobacter xylinum), which ferments the alcohols produced by the yeast(s) into acetic acid. This increases the acidity while limiting the alcoholic content of kombucha. The count of bacteria and yeast that were found to produce acetic acid increased for the first four days of fermentation and decreased after. Sucrose is broken up into fructose and glucose, and the bacteria and yeast break glucose into Gluconic acid, and fructose into acetic acid.[1] G. xylinum is responsible for most or all of the physical structure of a kombucha mother, and has been shown to produce microbial cellulose.[2] This is likely due to artificial selection by brewers over time, selecting for firmer and more robust cultures.

The acidity and mild alcoholic element of kombucha resists contamination by most airborne molds or bacterial spores. It was shown that Kombucha inhibits growth of harmful microorganisms such as E. coli, Sal. enteritidis, Sal. typhimurium, and Sh. Sonnei. [3] As a result, kombucha is relatively easy to maintain as a culture outside of sterile conditions. The bacteria and yeasts in kombucha promote microbial growth for the first six days of fermentation; after that, they steadily decline. Kombucha even has this antimicrobial effect after being heated and at a pH of 7. While this beverage inhibits growth of certain bacteria, it had no effect on the yeasts. This study also found that large proteins and catechins such as Epigallocatechin gallate also contributed to the antimicrobial properties of Kombucha. [4]

The kombucha culture can also be used to make an artificial leather.[5]

Kombucha contains multiple species of yeast and bacteria along with the organic acids, active enzymes, amino acids, and polyphenols produced by these microbes. The precise quantities of a sample can only be determined by laboratory analysis and vary depending on the fermentation method, but kombucha may contain any of the following: Acetic acid, Ethanol, Gluconic acid, Glucuronic acid, Glycerol, Lactic acid, Usnic acid and B-vitamins.[6][7][8] It was also found that Kombucha contains about 1.51 mg/mL of vitamin C. [9]

Another main ingredient found in all fermented foods and beverages are probiotics which are beneficial bacteria necessary for adequate digestion and absorption of nutrients. They are viable microorganisms that improve gut microflora by secreting enzymes, organic acids, vitamins, and nontoxic anti-bacterial substances once ingested. [10] Probiotics have also been shown to improve metabolism and treat antibiotic associated symptoms such as diarrhea. [11] In a recent study, alternative diets such as probiotics, green tea extract and Kombucha tea were fed to broiler chickens to measure the effects of growth and immunity. The chickens fed with Kombucha showed an increase in protein digestibility. The conclusion of the study stated, “adding Kombucha tea (20 % concentration) to wet wheat-based diets improved broiler performance and had a growth-promoting effect. Probiotic diets also resulted in enhanced growth and performance, but to a lesser extent.” [12]

According to the American Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, many Kombucha products contain more than 0.5% alcohol by volume, but some contain less.[13]

Many claims have focused on glucuronic acid,[14] a compound used by the liver for detoxification. The idea that glucuronic acid is present in kombucha is based on the observation that glucuronic acid conjugates (glucuronic acid waste chemicals) are increased in the urine after consumption. Early chemical analysis of kombucha brew suggested glucuronic acid was the key component, and researchers[citation needed] hypothesized that the extra glucuronic acid would assist the liver by supplying more of the substance during detoxification. These analyses were done using gas chromatography to identify the chemical constituents, but this method relies on having proper chemical standards [15] to match to the unknown chemicals.

Reports of adverse reactions may be related to unsanitary fermentation conditions, leaching of compounds from the fermentation vessels, or "sickly" kombucha cultures that cannot acidify the brew.[16] Cleanliness is important during preparation, and in most cases, the acidity of the fermented drink prevents growth of unwanted contaminants.

- ^ Sreeramulu, Guttapadu, Yang Zhu, and Wieger Knol. "Kombucha Fermentation and Its Antimicrobial Activity." J. Agric. Food Chem 48 (2000): 2589-594. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

- ^ Nguyen, Vu Tuan; Flanagan, Bernadine; Gidley, Michael J.; Dykes, Gary A. (2008). "Characterization of Cellulose Production by a Gluconacetobacter xylinus Strain from Kombucha". Current Microbiology. 57 (5): 449–53. doi:10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3. PMID 18704575.

- ^ Sreeramulu, Guttapadu, Yang Zhu, and Wieger Knol. "Kombucha Fermentation and Its Antimicrobial Activity." J. Agric. Food Chem 48 (2000): 2589-594. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

- ^ Sreeramulu, Guttapadu, Yang Zhu, and Wieger Knol. "Kombucha Fermentation and Its Antimicrobial Activity." J. Agric. Food Chem 48 (2000): 2589-594. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

- ^ "Suzanne Lee: Grow your own clothes". TED2011. March 2011.

- ^ Teoh, Ai Leng; Heard, Gillian; Cox, Julian (2004). "Yeast ecology of Kombucha fermentation". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 95 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020. PMID 15282124.

- ^ Dufresne, C.; Farnworth, E. (2000). "Tea, Kombucha, and health: A review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3.

- ^ Velicanski, Aleksandra; Cvetkovic, Dragoljub; Markov, Sinisa; Tumbas, Vesna; Savatovic, Sladjana (2007). "Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha". Acta periodica technologica (38): 165–72. doi:10.2298/APT0738165V.

- ^ Bauer-Petrovska, Bilijana, and Lidija Petrushevska-Tozi. "Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the Kombucha drink." International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 35.2 (2000): 201-05. Web. 3 Mar. 2014.

- ^ Afsharmanesh, M., and B. Sadaghi. "Effects of Dietary Alternatives (probiotic, Green Tea Powder, and Kombucha Tea) as Antimicrobial Growth Promoters on Growth, Ileal Nutrient Digestibility, Blood Parameters, and Immune Response of Broiler Chickens." Comparative Clinical Pathology (2013): n. pag. Springer Journals. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

- ^ Kligler, B., & Cohrssen, A. (2008). Probiotics. American Family Physician, 78(9), 1073-1078.

- ^ Afsharmanesh, M., and B. Sadaghi. "Effects of Dietary Alternatives (probiotic, Green Tea Powder, and Kombucha Tea) as Antimicrobial Growth Promoters on Growth, Ileal Nutrient Digestibility, Blood Parameters, and Immune Response of Broiler Chickens." Comparative Clinical Pathology (2013): n. pag. Springer Journals. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

- ^ "Kombucha FAQs". Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Mongrove (2009), Harvard University.

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ . 2007 http://www.webmd.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Phan, TG; Estell, J; Duggin, G; Beer, I; Smith, D; Ferson, MJ (1998). "Lead poisoning from drinking Kombucha tea brewed in a ceramic pot". The Medical journal of Australia. 169 (11–12): 644–6. PMID 9887919.