George M. Cohan

George M. Cohan | |

|---|---|

Cohan in 1908 | |

| Born | George Michael Cohan July 3, 1878 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | November 5, 1942 (aged 64) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Entertainer, playwright, composer, lyricist, actor, singer, dancer, producer |

| Spouse(s) | Ethel Levey (m. 1899 – 1907; divorced) Agnes Mary Nolan (m. 1907 – 1942; his death) |

| Children | Georgette Cohan Mary Cohan Helen Cohan George M Cohan, Jr. |

George Michael Cohan (July 3, 1878 – November 5, 1942), known professionally as George M. Cohan, was an American entertainer, playwright, composer, lyricist, actor, singer, dancer and producer.

Cohan began his career as a child, performing with his parents and sister in a vaudeville act known as "The Four Cohans." Beginning with Little Johnny Jones in 1904, he wrote, composed, produced, and appeared in more than three dozen Broadway musicals. Cohan published more than 300 songs during his lifetime, including the standards "Over There", "Give My Regards to Broadway", "The Yankee Doodle Boy" and "You're a Grand Old Flag".[1] As a composer, he was one of the early members of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). He displayed remarkable theatrical longevity, appearing in films until the 1930s, and continuing to perform as a headline artist until 1940.

Known in the decade before World War I as "the man who owned Broadway", he is considered the father of American musical comedy.[1] His life and music were depicted in the Academy Award-winning film Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) and the 1968 musical George M!. A statue of Cohan in Times Square in New York City commemorates his contributions to American musical theatre.

Early life and Education

Cohan was born in 1878 in Providence, Rhode Island, to Irish Catholic parents. A baptismal certificate (which gave the wrong first name for his mother) indicated that he was born on July 3, but Cohan and his family always insisted that George had been "born on the Fourth of July!" [2] He was the fourth member of the family vaudeville act called The Four Cohans, which included his father Jeremiah "Jere" (Keohane) Cohan (1848–1917),[3] mother Helen "Nellie" Costigan Cohan (1854–1928) and sister Josephine "Josie" Cohan Niblo (1876–1916).[2] In 1890, he toured as the star of a show called Peck's Bad Boy[4] and then joined the family act; The Four Cohans mostly toured together from 1890 to 1901. He and his sister made their Broadway debut in 1893 in a sketch called The Lively Bootblack. Temperamental in his early years, Cohan later learned to control his frustrations. During these years, Cohan originated his famous curtain speech: "My mother thanks you, my father thanks you, my sister thanks you, and I thank you."[4] Musicals101.com (2004), retrieved April 15, 2010</ref> George's parents were traveling vaudeville performers, and he joined them on stage while still an infant, first as a prop, learning to dance and sing soon after he could walk and talk.[citation needed]

Time in North Brookfield, Massachusetts

From a 2000 Telegram & Gazette Article:

First, he returned for Connie Mack Day, July 10, 1934 - he was a friend of the baseball legend, who was born and raised in nearby Brookfield, MA - and later, on October 30, 1934 when he brought the case to Eugene O’Neill’s “Ah Wilderness”, in which he was starring, to town for a single performance at the North Brookfield Town Hall.

“Gee, it’s great to be home again,” he was quoted as saying when he arrived. It was in North Brookfield, he told a newspaper reporter, “that I got the only smatterings of real boyhood that I have ever known.” During his preteen years in the late 1800s, young Cohan and his family, known on stage as “The Four Cohans”, spent their summer vacation from the vaudeville circuit at his grandmother’s home on Bell Street.

It was “quite a town,” Cohan wrote in his autobiography, “Twenty Years On Broadway”. “It always looked to me as though a scenic artist had painted it on the side of a hill,” he wrote. In the May 17, 1894 North Brookfield Journal Newspaper, it was said that “The talented Cohans are resting here after thirty week’s tour of several eastern, middle, southern, and western states”

Other newspaper accounts tell of the almost festive arrival of the Cohans - Jerry, his father; Helen, his mother; Josie, his sister; and George - in town for vacation season. It became a tradition that the family would give performance at the Town Hall during the summer. One newspaper account said a show "would be decidedly refreshing, after the kind of traveling shows our Town Hall patrons have had."

From the time the summer visits to North Brookfield to his death on November 5, 1942 in New York City, Cohan kept in contact with the many friends he is made as a youngster during the summer visits. Some even join him in New York. His pals Dennis F. O'Brien, Arthur F. Driscoll, and Edward C. Rafferty - all members, with Cohan, of the “Coughlin Disturbers”, a sandlot baseball team, eventually became lawyers and move to the city.

When Mr. O'Brien opened the law office, Cohan was the first client. “He's been my counselor and business adviser ever since" he wrote in his autobiography. Cohan’s memories of those good times in North Brookfield inspired a musical, "50 Miles From Boston," which is set North Brookfield.

Although it enjoyed brief popularity, the musical contain one of his most famous songs “Harrigan". The Cohans found the atmosphere in North Brookfield just what they needed to relax and prepare for another 40 week stint of performances.“This town was the Mirth Makers’ only chance to receive mirth instead of giving it, writes author John McCabe. “One might expect the children of this peaceful town to be in awe of this much traveled, cocky stranger from the outside world, but George quickly became the leader of the town youngsters."

Another account of those summer visits tells of the many mischievous activities of his "gag" of sandlot players. "Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn were pikers by comparison," the account states. "The hijinks that took place before and after baseball games, in fact all during the summer, has become local tradition."

As the years went on, Cohan began to turn from fun to fancy. In his autobiography, he writes about his families visit in the summer of 1895. It was about this time that he be in writing one-act plays. He said the relative quiet of North Brookfield allowed him to "go into seclusion" and turn out sketches "at the rate of not less than one week."

He tells of being urged by his parents to get out and play baseball with his friends, but says he felt more at home pounding out plays on his typewriter. By the time he returned to North Brookfield in 1934, he was the only member of his family still alive. Even so, the memories of the Four Cohans were very much alive in the minds of local residents. Newspaper accounts of the visit and performance of "Ah Wilderness" indicate that a huge crowd showed up for the event.

The 500 seats in the Town Hall were quickly filled and an estimated 1,000 people stood outside listening to the loudspeakers.

After the play, according to the newspaper accounts, Cohan returned to the stage. With his accompanist at the piano, he began singing his long list of hits. In the front row were many of his North Brookfield pals from his summer vacation days. "Each song, awaking the echoes in the old hall that had once echoed to his mother's voice, stirred memories, not only in the singer, but in the old friends listening," wrote a reporter. Members of the audience "couldn't get enough and stamped their feet, calling, ‘give us more Georgie’.”

Reading the old newspaper accounts, it is clear that the annual appearance of the Cohan family was big news in North Brookfield.

But the town’s impact on the family, and in particular, "George M.,” was important as well. When he returned with the cast of “Ah Wilderness”, in 1934, he told a reporter, “I’ve knocked around everywhere, but there’s no place like North Brookfield. The old place never changes.” [5]

Career

Early career

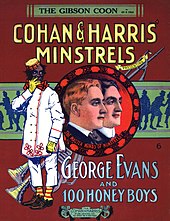

Cohan began writing original skits (over 150 of them) and songs for the family act in both vaudeville and minstrel shows while in his teens.[4] Soon he was writing professionally, selling his first songs to a national publisher in 1893. In 1901 he wrote, directed and produced his first Broadway musical, "The Governor's Son", for The Four Cohans.[4] His first big Broadway hit in 1904 was the show Little Johnny Jones, which introduced his tunes "Give My Regards to Broadway" and "The Yankee Doodle Boy."[6]

Cohan became one of the leading Tin Pan Alley songwriters, publishing upwards of 300 original songs[1] noted for their catchy melodies and clever lyrics. His major hit songs included "You're a Grand Old Flag," "Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway," "Mary Is a Grand Old Name," "The Warmest Baby in the Bunch," "Life's a Funny Proposition After All," "I Want To Hear a Yankee Doodle Tune," "You Won't Do Any Business If You Haven't Got a Band," "The Small Town Gal," "I'm Mighty Glad I'm Living, That's All," "That Haunting Melody," "Always Leave Them Laughing When You Say Goodbye", and America's most popular World War I song "Over There",[4] which was recorded by Enrico Caruso among others.[7]

From 1904 to 1920, Cohan created and produced over fifty musicals, plays and revues on Broadway together with his friend Sam Harris,[4][8] including Give My Regards to Broadway and the successful Going Up in 1917, which became a smash hit in London the following year.[9] His shows ran simultaneously in as many as five theatres. One of Cohan's most innovative plays was a dramatization of the mystery Seven Keys to Baldpate in 1913, which baffled some audiences and critics but became a hit. Cohan dropped out of acting for some years after his 1919 dispute with Actors' Equity Association, described below.[4]

In 1925, he published his autobiography, Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took To Get There.[10]

Later career

Cohan appeared in 1930 in a revival of his tribute to vaudeville and his father, The Song and Dance Man.[4] In 1932, Cohan starred in a dual role as a cold, corrupt politician and his charming, idealistic campaign double in the Hollywood musical film The Phantom President. The film co-starred Claudette Colbert and Jimmy Durante, with songs by Rodgers and Hart, and was released by Paramount Pictures. He appeared in some earlier silent films but he disliked Hollywood production methods and only made one other sound film, Gambling (1934), based on his own 1929 play and shot in New York City. A critic called Gambling a "stodgy adaptation of a definitely dated play directed in obsolete theatrical technique."[11] It is considered a lost film.[12]

Cohan earned acclaim as a serious actor in Eugene O'Neill's only comedy, Ah, Wilderness! (1933), and in the role of a song-and-dance President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Rodgers and Hart's musical I'd Rather Be Right (1937). The same year, he reunited with Harris to produce a play called Fulton of Oak Falls, starring Cohan. His final play, The Return of the Vagabond (1940), featured a young Celeste Holm in the cast.[13]

In 1940, Judy Garland played the title role in a film version of his 1922 musical Little Nellie Kelly. Cohan's mystery play Seven Keys to Baldpate was first filmed in 1916 and has been remade seven times, most recently as House of Long Shadows (1983), starring Vincent Price. In 1942, a musical biopic of Cohan, Yankee Doodle Dandy, was released, and James Cagney's performance in the title role earned the Best Actor Academy Award. The film was privately screened for Cohan as he battled the last stages of abdominal cancer; Cohan’s comment on Cagney’s performance was, "My God, what an act to follow!"[14] Cohan's 1920 play The Meanest Man in the World was filmed with Jack Benny in 1943.[citation needed]

Cohan died of cancer at the age of 64 on November 5, 1942, at his Manhattan apartment on Fifth Avenue. After a large funeral at St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York, Cohan was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, in a private family mausoleum he had erected a quarter century earlier for his sister and parents.[4]

Legacy

Although Cohan is mostly remembered for his songs, he became an early pioneer in the development of the "book musical", bridging the gaps in his libretti between drama and music, operetta and extravaganza. More than three decades before Agnes de Mille choreographed Oklahoma!, Cohan used dance not merely as razzle-dazzle but to advance the plot. The engaging books of his musicals supported the scores that yielded so many popular songs. As a storyteller, Cohan's main characters were "average Joes and Janes." Characters like Johnny Jones and Nellie Kelly appealed to a whole new audience. He wrote for every American instead of highbrow Americans.[15]

In 1914, Cohan became one of the founding members of ASCAP.[16] Although Cohan was known as extremely generous to his fellow actors in need,[4] in 1919, he unsuccessfully opposed a historic strike by Actors' Equity Association, for which many in the theatrical professions never forgave him. Cohan opposed the strike because in addition to being an actor in his productions, he was also the producer of the musical that set the terms and conditions of the actors' employment. During the strike, he donated $100,000 to finance the Actors' Retirement Fund in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. After Actors' Equity was recognized, Cohan refused to join the union as an actor, which hampered his ability to appear in his own productions. Cohan sought a waiver from Equity allowing him to act in any theatrical production. In 1930, Cohan won a law case against the Internal Revenue Service that allowed the deduction, for federal income tax purposes, of his business travel and entertainment expenses, even though he was not able to document them with certainty. This became known as the "Cohan rule" and is frequently cited in tax cases.[17]

Cohan wrote numerous Broadway musicals and straight plays in addition to contributing material to shows written by others—more than 50 in all.[4] Cohan shows included Little Johnny Jones (1904), Forty-five Minutes from Broadway (1905), George Washington, Jr. (1906), The Talk of New York and The Honeymooners (1907), Fifty Miles from Boston and The Yankee Prince (1908), Broadway Jones (1912), Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913), The American Idea, Get Rich Quick Wallingford, The Man Who Owns Broadway, Little Nellie Kelley, The Cohan Revue of 1916 (and 1918; co-written with Irving Berlin), The Tavern (1920), The Rise of Rosie O'Reilly (1923, featuring a 13-year-old Ruby Keeler among the chorus girls), The Song and Dance Man (1923), Molly Malone, The Miracle Man, Hello Broadway, American Born (1925), The Baby Cyclone (1927, one of Spencer Tracy's early breaks), Elmer the Great (1928, co-written with Ring Lardner), and Pigeons and People (1933).[4] At this point in his life, he walked in and out of retirement.[16]

Cohan was called "the greatest single figure the American theatre ever produced – as a player, playwright, actor, composer and producer."[4] On June 29, 1936, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal for his contributions to World War I morale, in particular the songs "You're a Grand Old Flag" and "Over There."[16] Cohan was the first person in any artistic field selected for this honor, which previously had gone only to military and political leaders, philanthropists, scientists, inventors, and explorers.

In 1959, at the behest of lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, a $100,000 bronze statue of Cohan was dedicated in Times Square at Broadway and 46th Street in Manhattan. The 8-foot bronze remains the only statue of an actor on Broadway.[18] He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970,[16] and into the American Folklore Hall of Fame in 2003.[citation needed] His star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 6734 Hollywood Boulevard.[19] Cohan was inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame on October 15, 2006.[20]

The United States Postal Service issued a 15-cent commemorative stamp honoring Cohan on the anniversary of his centenary, July 3, 1978. The stamp depicts both the older Cohan and his younger self as a dancer, along with the tag line "Yankee Doodle Dandy." It was designed by Jim Sharpe.[21] On July 3, 2009, a bronze bust of Cohan, by artist Robert Shure, was unveiled at the corner of Wickenden and Governor Streets in Fox Point, Providence, a few blocks from his birthplace. The city renamed the corner the George M. Cohan Plaza and announced an annual George M. Cohan Award for Excellence in Art & Culture. The first award went to Curt Columbus, the artistic director of Trinity Repertory Company.[22]

Personal life

From 1899 to 1907, Cohan was married to Ethel Levey (1881–1955), a musical comedy actress and dancer who joined the Four Cohans when his sister married. Levey and Cohan had a daughter, actress Georgette Cohan Souther Rowse (1900–1988). He married again in 1908, to Agnes Mary Nolan (1883–1972), who had been a dancer in his early shows; they remained married until his death, living for several years at 6 Times Square in New York City. They had two daughters and a son. The eldest was Mary Cohan Ronkin, a cabaret singer in the 1930s, who composed incidental music for her father's play The Tavern. In 1968, Mary supervised musical and lyric revisions for the Broadway play George M!.[23][24] Their second daughter was Helen Cohan Carola, a film actress, who performed on Broadway with her father in Friendship in 1931.[25][26]

Their youngest child was George Michael Cohan, Jr. (1914–2000), who graduated from Georgetown University and served in the entertainment corps during World War II. In the 1950s, George Jr. reinterpreted his father's songs on recordings, in a nightclub act, and in television appearances on the Ed Sullivan and Milton Berle shows. George Jr.'s only child, Michaela Marie Cohan (1943–1999), was the last descendant named Cohan. She graduated with a theater degree from Marywood College, Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1965. From 1966 to 1968, she served in a civilian Special Services unit in Vietnam and Korea.[27] In 1996, she stood in for her ailing father at the ceremony marking her grandfather's induction into the Musical Theatre Hall of Fame, at New York University.[4]

Cohan was a devoted baseball fan, regularly attending games of the former New York Giants.[4]

In popular culture

- Cohan spent childhood summers with his relatives in Podunk (now part of East Brookfield), Massachusetts.[28] He loved Podunk and its "hayseed hicks" and made it famous, describing it in his comedy acts. Other entertainers started mentioning Podunk to mean a place of little significance.[29]

- As noted above, James Cagney played Cohan in the 1942 biopic Yankee Doodle Dandy. Cagney played Cohan once more in the 1955 film The Seven Little Foys, starring Bob Hope as the vaudevillian Eddie Foy. Cagney performed this role free of charge as an expression of his gratitude to Eddie Foy Sr., who had done Cagney a favor during Cagney's early vaudeville days.

- Mickey Rooney played Cohan in Mr. Broadway, a television special broadcast on NBC on May 11, 1957. The same month, Rooney released a 78 RPM record: The A-side featured Rooney singing Cohan's best-known songs, and the B-side featured Rooney singing several of his own compositions, such as the maudlin "You Couldn't Count the Raindrops for the Tears."

- Joel Grey starred on Broadway as Cohan in the musical George M! (1968), which was adapted into a NBC television special in 1970.

- Allan Sherman sang a parody-medley of three Cohan tunes on an early album: "Barry (That'll Be the Baby's Name)"; "H-o-r-o-w-i-t-z"; and "Get on the Garden Freeway" to the tune of "Mary's a Grand Old Name", "Harrigan" and "Give My Regards to Broadway", respectively.

- Chip Deffaa created a one-man show about the life of Cohan called George M. Cohan Tonight!, which first ran Off-Broadway at the Irish Repertory Theatre in 2006 with Jon Peterson as Cohan.[30] Deffaa has written and directed five other plays about Cohan.[31]

Notes

- ^ a b c Benjamin, Rick. "The Music of George M. Cohan". Liner notes to You're a Grand Old Rag – The Music of George M. Cohan. New World Records.

- ^ a b Kenrick, John. "George M. Cohan: A Biography". Cohan started as a child performer at age 8, first on the violin and then as a dancer."Obituary: George M. Cohan, 64, Dies at Home Here". The New York Times, November 6, 1942

- ^ Cullen, Frank; Hackman, Florence; and Neilly, Donald (eds.). Vaudeville, Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, p. 243

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Cite error: The named reference

obitwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ http://nl.newsbank.com/nl-search/we/Archives?p_product=WO&p_theme=wo&p_action=search&p_maxdocs=200&s_dispstring=allfields(cohan)%20AND%20date(7/2/2000%20to%207/2/2000)&p_field_date-0=YMD_date&p_params_date-0=date:B,E&p_text_date-0=7/2/2000%20to%207/2/2000)&p_field_advanced-0=&p_text_advanced-0=(%22cohan%22)&xcal_numdocs=50&p_perpage=25&p_sort=YMD_date:D&xcal_useweights=no

- ^ Kenrick, John. "Cohan Bio: Part II:Little Johnny Jones". Musicals101.com (2002), retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Duffy, Michael. "Vintage Audio - Over There", FirstWorldWar.com, August 22, 2009, accessed July 12, 2013

- ^ "Cohan & Harris". Internet Broadway Database listing, ibdb.com, accessed April 19, 2010

- ^ "Over There, 1910-1920" talkinbroadway.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took To Get There". Listing at openlibrary.org, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Koszarski, Richard (2008-08-27). Hollywood On the Hudson: Film and Television in New York from Griffith to Sarnoff. Rutgers University Press. pp. 283–284. ISBN 978-0-8135-4552-3. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ McCabe, p. 229

- ^ Kenrick, John. "Cohan Bio: Part III: Comebacks". Musicals101.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)". RogerEbert.com, July 5, 1998, accessed July 4, 2011

- ^ Hischak, Thomas S. Boy Loses Girl ISBN 0-8108-4440-0

- ^ a b c d "George M. Cohan". Songwritershalloffame.org, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan, Petitioner v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent". United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, 39 F.2d 540 (March 3, 1930), retrieved April 22, 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan Statue". New York City Parks Department site, Nycgovparks.org, accessed April 19, 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan star location". Hollywoodchamber.net.vhost.zerolag.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "George M. Cohan". Limusichalloffame.org, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Many Honor Patriot Cohan". Spokane Daily Chronicle, July 4, 1978

- ^ Dujardin, Richard C. "Sculpture of Providence native George M. Cohan is unveiled in Fox Point". The Providence Journal, July 4, 2009, accessed April 19, 2010

- ^ "Mary Cohan Finally Elopes and Marries George Ranken". St. Petersburg Times, March 7, 1940

- ^ George M! Tams-witmark.com, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Helen Cohan". Internet Broadway Database listing, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Helen Cohan". Internet Movie Database listing, retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ Cook, Louise. "Michaela Cohan". The Free Lance Star, October 25, 1968

- ^ Macht, Norman L. "Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball", University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 20 ISBN 0803209908

- ^ Yankee Magazine excerpts in "The Eugene O'Neill Newsletter", Vol. III, No. 1, May, 1979, accessed March 3, 2013

- ^ George M. Cohan Tonight! on the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- ^ "George M. Cohan Shows". Georgemcohan.org, accessed 16 August 2010

References

- Cohan, George M. Twenty Years on Broadway. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1924.

- Gilbert, Douglas. American Vaudeville: Its Life and Times. New York: Dover Publications, 1963.

- Jones, John Bush. Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical Theatre. Lebanon, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2003 (pp. 15–23).

- McCabe, John. George M. Cohan: The Man Who Owned Broadway. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1973.

External links

- George M. Cohan at IMDb

- George M. Cohan at the Internet Broadway Database

- George M. Cohan at Internet off-Broadway Database

- George M. Cohan In America's Theater

- George M. Cohan on musicals101.com

- George M. Cohan at Find a Grave

- F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre, "Dancing after retirement: Cohan plays Roosevelt, 1937", New York Daily News, March 20, 2004. [1]

- Template:Fr icon Présentation de James Cagney et de Yankee doodle dandy sur le site d'analyse L'oBservatoire (simple appareil).

- Chip Deffaa's extensive George M. Cohan site

- George M. Cohan; PeriodPaper.com c. 1910

- Sheet music for "Over There", Leo Feist, Inc., 1917.

- Finding aid for the Edward B. Marks Music Co. Collection on George M. Cohan, 1901-1968 at the Museum of the City of New York

- 1878 births

- 1942 deaths

- American male singers

- American musical theatre composers

- American people of Irish descent

- American singer-songwriters

- Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx)

- Cancer deaths in New York

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- People from Providence, Rhode Island

- Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees

- Vaudeville performers