Malaria

Malaria (Italian bad air; formerly called ague in English) is an infectious disease which causes about half a billion infections and two million deaths annually, mainly in tropical countries and especially in sub-Saharan Africa. The protozoan cause of malaria was discovered by a French army doctor, Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1907.

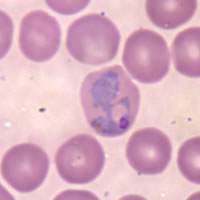

Malaria is caused by the protozoan parasite Plasmodium (one of the Apicomplexa). The recognised species causing disease in man are P. falciparum (which alone accounts for 80% of the recognised cases and ~90% of the deaths) and P. vivax, but P. ovale, P. malariae, P. knowesli and P. semiovale are also known to cause malaria. The vector for human malarial parasite is the Anopheles mosquito.

Other mammals (bats, rodents, non-human primates) as well as birds and reptiles also suffer from malaria.

Symptoms of malaria include fever, shivering, arthralgia (joint pain), vomiting, and convulsions. There may be the feeling of tingling in the skin, particularly with malaria caused by P. falciparum. Complications of malaria include coma and death if untreated—young children are especially vulnerable.

Mechanism of the disease

Infected female Anopheles mosquitoes carry Plasmodium sporozoites in their salivary glands. If they bite a person, which they usually do starting at dusk and during the night, the sporozoites enter the person's body via the mosquito's saliva, migrate to the liver where they multiply within hepatic liver cells. They then turn into merozoites which then enter red blood cells. There they multiply further, periodically breaking out of the red blood cells. The classical description of waves of fever coming every three or four days arises from simultaneous waves of merozoites breaking out of red blood cells during the same day.

The parasite is relatively protected from attack by the body's immune system because it stays inside liver and blood cells. However, circulating infected blood cells are killed in the spleen. To avoid this fate, the parasite produces certain surface proteins which infected blood cells express on their cell surface, causing the blood cells to stick to the walls of blood vessels. These surface proteins are highly variable and cannot serve as a reliable target for the immune system. The stickiness of the red blood cells are particularly pronounced in Plasmodium falciparum malaria and this is the main factor giving rise to hemorrhagic complications of malaria.

Some merozoites turn into male and female gametocytes. If a mosquito bites the infected person and picks up gametocytes with the blood, fertilization occurs in the mosquito's gut, new sporozoites develop and travel to the mosquito's salivary gland, completing the cycle.

Pregnant women are especially attractive to the mosquitoes, and malaria in pregnant women is an important cause of still births and infant mortality.

Treatment and prevention

If diagnosed early, malaria can be treated, but prevention is always much better, and substances that inhibit the parasite are widely used by visitors to the tropics. Since the 17th century quinine has been the prophylactic of choice for malaria. The development of quinacrine, chloroquine, and primaquine in the 20th century reduced the reliance on quinine. These anti-malarial medications can be taken preventively, which is recommended for travellers to affected regions.

Certain strains of Plasmodium have recently developed resistance to chloroquine which has been the first line of treatment in many countries, thus complicating the treatment. In West Africa, where the local strains of malaria are particularly virulent, Lariam is now the recommended prophylactic, despite causing psychological problems in some vulnerable people. Doxycycline, an antibiotic, is also prescribed as a prophylactic against quinine-resistant malaria, though its use is less common than Lariam because it must be consumed daily. It seems inevitable that resistance to these drugs will also occur.

In addition to the antimalarial drugs, the use of mosquito repellents such as DEET, and mosquito nets and screens can reduce the chance of malaria, as well as the discomfort of insect bites.

Extracts from the plant Artemisia (specifically Artemisia annua), containing the compound artemisinin, a substance unrelated to the quinine derivatives, offer some future promise.

Prospects of disease control

Vaccines for malaria are under development, but no effective vaccine exists as of 2004. It is hoped that the genome sequence of the most deadly agent of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, which was completed in 2002, will provide targets for new drugs or vaccines.

Efforts to eradicate malaria by attacking mosquitos have been successful in some areas. Malaria was once common in the United States and southern Europe, but the draining of wetland breeding grounds and better sanitation eliminated it from affluent regions.

Malaria was eliminated from the northern parts of the USA in the early twentieth century, and the use of the pesticide DDT during the 1950s eliminated it from the south.

Sterile insect technique is emerging as a potential method to control malaria carrying mosquitos. Progress towards making a version of this approach which would utilise genetically modified insects a reality has been made by researchers at Imperial College London who have created the world's first transgenic malaria mosquito.

A major public health effort to eradicate malaria by selectively targeting mosquitos in areas where malaria was rampant was embarked upon in the 1950s and 1960s. (The Mosquito Killer—PDF of the same article)

Since most of the deaths today occur in poor rural areas of Africa which lack health care, the distribution to children of mosquito nets impregnated with insect repellants has been suggested as the most cost-effective prevention method. These nets can often be obtained for less than US$10 or 10 euros when purchased in bulk from the United Nations or other organizations.

Some advocates believe that DDT spraying is even cheaper and more effective than nets, and charge that environmentalists have created perverse restrictions on DDT use that have multiplied African malaria deaths into the millions in countries where the disease had been all but eradicated.

Sickle cell anemia and other genetic effects

Carriers of the sickle cell anaemia gene are protected against malaria because of their particular hemoglobin mutation; this explains why sickle cell anemia is particularly common among people of African origin. There is a theory that another hemoglobin mutation, which causes the genetic disease thalassemia, may also give its carriers an enhanced immunity to malaria.

Another disease that gives protection against malaria is glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). It protects against malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum as the presence of this enzyme is critical to survival of these parasites within red blood cells.

It is thought that humans have been afflicted by malaria for about 50,000 years, and several human genes responsible for blood cell proteins and the immune system have been shaped by the struggle against the parasite.