Southern Ireland (1921–1922)

| Southern Ireland Deisceart na hÉireann | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of the United Kingdom | |||||||||

| 1921–1922 | |||||||||

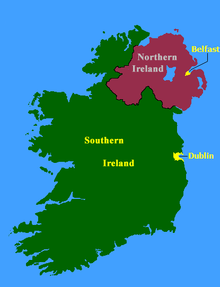

Location of Southern Ireland (dark green) – in Europe (green & grey) | |||||||||

| Capital | Dublin | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Devolved government within constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Chairman | |||||||||

• First | Michael Collins | ||||||||

• Last | W.T. Cosgrave | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliamenta | ||||||||

• Upper house | Senate | ||||||||

• Lower house | House of Commons | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 3 May 1921 | |||||||||

| 6 December 1921 | |||||||||

| 6 December 1922 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| a. A Council of Ireland was also envisaged with "a view to the eventual establishment of a Parliament for the whole of Ireland" (Source: GOI Act) | |||||||||

Southern Ireland was a part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It covered the same area that the independent state of Ireland comprises today, about five sixths of the island of Ireland. Southern Ireland had a brief existence. Legally, it was established on 3 May 1921, the same day Northern Ireland was.[1] It was dissolved at approximately 1pm on 6 December 1922 when the King (at a meeting of his Privy Council at Buckingham Palace)[2] signed a proclamation establishing the new Irish Free State.[3] Some of Southern Ireland's institutions only existed on paper. Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland were both established under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. A Provisional Government of Southern Ireland was established pursuant to the Anglo Irish Treaty.

Home Rule and partition

The Government of Ireland Act 1920, also known as the Fourth Home Rule Act, was intended to provide a solution to the problem that had bedevilled Irish politics since the 1880s, namely the conflicting demands of Irish unionists and nationalists. Nationalists wanted a form of home rule, believing that Ireland was poorly served by the Government in Westminster and its Irish Executive in Dublin Castle. Unionists feared that a nationalist government in Dublin would discriminate against Protestants and would impose tariffs that would unduly hit the north-eastern counties of Ireland (these counties all being located within the province of Ulster), which were not only predominantly Protestant but also the only industrial area on an island whose economy was largely agricultural. Unionists imported arms and assorted weapons from Germany and established the Ulster Volunteer Force (the UVF) to prevent Home Rule in Ulster. In response to this, nationalists also imported arms and set up the Irish Volunteers. Partition, which was introduced by the Government of Ireland Act, was intended as a temporary solution, allowing Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland to be governed separately as regions of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. One of those most opposed to this partition settlement was the leader of Irish unionism, Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson, who felt that it was wrong to divide Ireland in two. He felt this would badly affect the position of southern and western unionists.

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act, passed at the end of December 1920, envisaged that Southern Ireland would have the following institutions:[4]

- a Parliament of Southern Ireland, consisting of the King, the Senate of Southern Ireland, and the House of Commons of Southern Ireland;

- a Government of Southern Ireland;

- the Supreme Court of Judicature of Southern Ireland;

- the Court of Appeal in Southern Ireland; and

- His Majesty's High Court of Justice in Southern Ireland.

It was also envisaged that Southern Ireland would share the following institutions with Northern Ireland:

- the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland - existing throughout the life of Southern Ireland, with the incumbent, Lord FitzAlan-Howard, continuing in office as Lord Lieutenant;

- a Council of Ireland - never established; and

- a High Court of Appeal for Ireland - which was established,[5] and heard a small number of cases before its abolition under the UK's Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Act 1922.

The Council of Ireland was to be established "with a view to the eventual establishment of a Parliament for the whole of Ireland", but it never came into being. The notable exception to the failure of the institutions of Southern Ireland was its courts, all of which functioned.[citation needed]

Parliamentary elections, 1921

While Northern Ireland did become a functioning entity, with a parliament and government that existed until 1972, Southern Ireland's Parliament, although legally established, never functioned (for example, it never passed an Act). The House of Commons of Southern Ireland met just once with only four members present. An Irish Republic had been proclaimed by the parliament known as Dáil Éireann, formed by Sinn Féin MPs elected from Ireland in the United Kingdom general election in 1918. Parliamentary elections under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 were held in May 1921. The first general election to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland in 1921, and the simultaneous general election to the House of Commons of Northern Ireland, was used by Sinn Féin to produce a single extrajudicial parliament, the Second Dáil. In the Southern Ireland constituencies Sinn Féin won 124 of the 128 seats, all without contest, while in the contested elections in Northern Ireland constituencies it secured six of the 52 seats, another six going to non-Sinn Féin nationalists. (The other four Southern seats were won by Dublin Unionists, who along with the 40 Unionists elected in the North, declined to participate in the second Dáil.) When the new Parliament of Southern Ireland was called into session in June 1921, only the four Unionist members of the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, and a handful of appointed senators, turned up in the Royal College of Science in Dublin, where the meeting was scheduled to take place; most of the others convened elsewhere as the Dáil.

Treaty and Free State

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was further ratified on the Irish side on 14 January 1922 by "a meeting summoned for the purpose [of approving the Treaty] of the members elected to sit in the House of Commons of Southern Ireland"[6] The Treaty, in specifying a "meeting of members", did not say that the Treaty needed to be approved by the House of Commons of Southern Ireland as such. The difference is subtle but was fully grasped by those who entered the Treaty. Hence, when that "meeting" was convened, it was convened by Arthur Griffith in his capacity as "Chairman of the Irish Delegation of Plenipotentiaries" (who had signed the Treaty). Notably, it was not convened by Viscount FitzAlan, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who, under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, was the office-holder with the entitlement to convene a meeting of the House of Commons of Southern Ireland.

The Provisional Government of Southern Ireland envisaged under the Treaty was constituted on 14 January 1922 at the above-mentioned meeting of members of the Parliament elected for constituencies in Southern Ireland. It took up office two days later when Michael Collins became Chairman of the Provisional Government. Collins took charge of Dublin Castle at a ceremony attended by Lord FitzAlan. The new Government was not an institution of Southern Ireland as envisaged under the Government of Ireland Act. Instead, it was a Government established under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and was a necessary transitional entity before the establishment of the Irish Free State on 6 December 1922.

Southern Ireland was self-governing but was not a sovereign state. Its constitutional roots remained the Acts of Union, two complementary Acts, one passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, the other by the Parliament of Ireland.

On 27 May 1922 (some months before the establishment of the Irish Free State) Lord FitzAlan, as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, in accordance with the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922 formally dissolved the Parliament of Southern Ireland and by proclamation called "a Parliament to be known as and styled the Provisional Parliament".[7] From that date, the Parliament of Southern Ireland itself ceased to exist. With the establishment of the Irish Free State on 6 December 1922 under the terms of the Treaty, Southern Ireland ceased to exist.

See also

References

- ^ Statutory Rules & Orders published by authority, 1921 (No. 533). Additional source for 3 May 1921 date: Alvin Jackson, Home Rule – An Irish History, Oxford University Press, 2004, p198; Southern Ireland did not become a state (or pejoratively, a statelet). Its constitutional roots remained the Act of Union, two complementary Acts, one passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, the other by the Parliament of Ireland.

- ^ The Times, Court Circular, Buckingham Palace, 6 Dec. 1922.

- ^ Copyright, 1922, by The New York Times Company. By Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES. (7 December 1922). "''New York Times'', 6 December 1922". New York Times. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Government of Ireland Act 1920

- ^ Austen Morgan, Belfast Agreement, pg. 34 wherein the author notes: "One all-Ireland institution – the High Court of Appeal for Ireland in section 38 [of the 1920 Act – did exist briefly.

- ^ Anglo-Irish Treaty.

- ^ Macardle (1999), p718 and DCU Website.