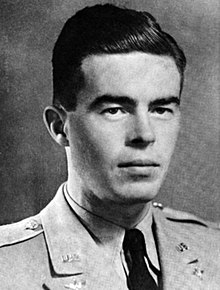

John Birch (missionary)

John Morrison Birch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 28, 1918 |

| Died | August 25, 1945 (aged 27) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Mercer University |

| Occupation(s) | Missionary, Military intelligence officer |

| Known for | Killed by Chinese communists |

John Morrison Birch (May 28, 1918 – August 25, 1945) was an American military intelligence officer and Baptist missionary in World War II, who was killed during a confrontation with supporters of the Communist Party of China.

Politically conservative groups in the United States consider him to be a martyr and the first victim of the Cold War. The John Birch Society, an American conservative organization formed 13 years after his death, was named in his honor. His parents joined the Society as Life Members.

Early life

Birch was born to Baptist missionaries in Landour, a hill station in the Himalayas now in the northern India state of Uttarakhand, at the time in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. In 1920, when he was two, the family returned to the United States. Birch was raised in New Jersey, Floyd County, Georgia,[1] and Macon, Georgia, in the Fundamental Baptist[1] tradition. He graduated from Lanier High School for Boys, now Central High School, followed by Georgia Baptist–affiliated Mercer University in 1939 magna cum laude.[1] "He was always an angry young man, always a zealot", said a classmate many years later. In his senior year at Mercer, he organized a student group to identify cases of heresy by professors, seeking to uphold the Scriptural definition of conversion and other doctrines.[2]

Missionary work

While a student at Mercer, Birch decided to become a missionary. He enrolled in J. Frank Norris' Fundamental Baptist Bible Institute,[1] Fort Worth, Texas. Completing the two-year curriculum in a single year, he was sent to China by the World Fundamental Baptist Missionary Fellowship.[1] Arriving in Shanghai in 1940, he began an intensive study of Mandarin Chinese. After six months, he was assigned to Hangzhou, an area as yet occupied by the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese sent troops to Hangzhou to arrest Birch as an enemy national. He and the other missionaries fled inland. Cut off from the outside world, Birch began trying to establish new missions in Zhejiang province.[2]

Military career

In April 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and his crew crash-landed in China after the Tokyo raid. They had flown from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8), bombed Tokyo, then flown to the Chinese mainland. After bailing out, they were rescued by Chinese civilians and smuggled by river into Zhejiang province. Birch went to meet them, assisting them and directing them to friendly territory.

When Doolittle arrived in Chongqing, he told Colonel Claire Chennault, leader of the Flying Tigers, about Birch's help. Chennault said he could use a Chinese-speaking American who knew the country well and he commissioned Birch as a first lieutenant, though Birch later wrote he would have been willing to serve as a private.[citation needed]

Birch joined the Fourteenth Air Force on its formation on 5 March 1943 and was later seconded to the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS). He stated he would be willing to be accepted into the OSS only if he was allowed to work as normally as he had before. He built a formidable intelligence network of sympathetic Chinese informants, supplying Chennault with information on Japanese troop movements and shipping, often performing dangerous incognito field assignments, during which he would brazenly hold Sunday church services for Chinese Christians. In his diary, Major Gustav Krause, commanding officer of the base, noted: "Birch is a good officer, but I'm afraid is too brash and may run into trouble."[3] Urged to take a leave of absence, Birch refused, telling Chennault he would not quit China "until the last Jap" did; he was equally contemptuous of Communists. He was promoted to captain and received the Legion of Merit in 1944.[2]

Death

V-J Day, August 14, 1945, signaled the end of formal hostilities; but, under terms of the Japanese surrender, the Japanese Army was ordered to continue occupying areas it controlled until they could hand power over to the Nationalist government, even in places where the Communist-led government had been the de facto state for a decade. This led to continued fighting as the People's Liberation Army fought to expel all imperial forces, a category it perceived to include U.S. personnel now openly collaborating with the remaining Japanese forces.

On August 25, as Birch was leading a party of Americans, Chinese Nationalists, and Koreans on a mission to reach Allied personnel in a Japanese prison camp, they were stopped by Chinese Communists near Xi'an. Birch was asked to surrender his revolver; he refused and harsh words and insults were exchanged. Birch was shot and killed; a Chinese Nationalist colleague was also shot and wounded but survived. The rest of the party was imprisoned but released shortly. Birch was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Memorials

Birch is known today mainly by the society that bears his name although Jimmy Doolittle, who met Birch after Doolittle's raid on Tokyo, said in his autobiography that he was sure that Birch "would not have approved". His name is on the bronze plaque of a World War II monument at the top of Coleman Hill Park overlooking downtown Macon, along with the names of other Macon men who lost their lives while serving in the military. Birch has a plaque on the sanctuary of the First Southern Methodist Church of Macon, which was built on land given by his family, purchased with the money he sent home monthly. A building at the First Baptist Church of Fort Worth, Texas, was named The John Birch Hall by Pastor J. Frank Norris.[4] The "John Birch Reel", a folk dance in which dancers consistently "move to the Right," satirizes John Birch's politics. [5] A small street in Townsend, Massachusetts, John Birch Memorial Drive, is also named for him.[6][citation needed]

Awards

- Distinguished Service Medal (posthumous)

- Legion of Merit

- Purple Heart (posthumous)

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two campaign stars

- World War II Victory Medal

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e The Secret File on John Birch, James & Marti Hefley, Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 1980, ISBN 0-8423-5862-5

- ^ a b c "Who Was John Birch?". Time. April 14, 1961.

- ^ Manchester, William (2013). The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932-1972. RosettaBooks. ISBN 9780795335570.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help), Ch. 13 - ^ Stokes, David R. (2011). The Shooting Salvationist: J. Frank Norris and the Murder Trial that Captivated America. Hanover, NH: Steerforth Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-58642-186-1

- ^ "John Birch Reel". YouTube. 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ^ "Maps". Bing Maps. Microsoft Bing. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

References

- I Could Never Be So Lucky Again, autobiography by James "Jimmy" Doolittle, ISBN 0-553-58464-2

- Mission to Yenan: American Liaison with the Chinese Communists 1944–1947, Carolle J. Carter, ISBN 0-8131-2015-2

- The Secret File on John Birch, James Hefley, Hannibal Books, 1995 (updated version), ISBN 0-929292-80-4

- The Life of John Birch, Robert Welch, Western Islands, ISBN 0-88279-116-8

External links

- 1918 births

- 1945 deaths

- American anti-communists

- American Christian missionaries

- American people of English descent

- Baptist missionaries

- Baptists from the United States

- Christian missionaries in China

- Deaths by firearm in China

- Mercer University alumni

- Murdered missionaries

- People from Dehradun district

- People from Macon, Georgia

- People of the Office of Strategic Services

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- World War II spies for the United States

- American people murdered abroad