Jacob van Ruisdael

Jacob van Ruisdael | |

|---|---|

The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, 1670 | |

| Born | 1628 or 1629 |

| Died | 10 March 1682 |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | Landscape painting |

| Notable work | The Jewish Cemetery, Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, View of Haarlem with bleaching fields |

| Movement | Dutch Golden Age |

| Patron(s) | Cornelis de Graeff (1599–1664) |

Jacob Isaackszoon van Ruisdael Dutch: [ˈrœysdaːl] (c.1629 – 10 March 1682) was the pre-eminent Dutch Golden Age landscape painter. He was prolific and versatile, depicting a wide variety of landscape subjects.

Jacob is the most famous of four family members who created landscape paintings, some of whom spelled their name Ruysdael: his well-known uncle Salomon van Ruysdael, his father Isaack van Ruisdael, and his cousin, confusingly called Jacob van Ruysdael. Attributions among the family members, as well as a wider group of Haarlem landscape painters, are uncertain as not all works are signed and dated.

During his early phase, the Haarlem years, starting in 1646, Ruisdael predominantly painted Dutch countryside scenes, of, for a teenager, remarkable quality. In 1650 he travelled to the German border and started painting monumental scenes. In his final stage, while living and working in Amsterdam, he added city panoramas and seascapes to his regular repertoire, in which the sky often took up two thirds of the canvas. Waterfalls feature often in his oeuvre. Unlike the other great Dutch landscape painters, he did not aim at a pictorial record of particular scenes, but he carefully thought out and arranged his compositions, introducing into them an infinite variety of subtle contrasts in the formation of the clouds, the plants and tree forms, and the play of light.

Only one of his pupils is known by name, the renowned Meindert Hobbema, one of several artists who painted figures in Ruisdael's landscapes, something he rarely did himself. Ruisdael is considered the most important member of the Haarlem Landscape School which is used to pinpoint a group of paintings that have retained their value over the centuries, not all of which can be attributed to a specific painter, but which can be attributed to a specific style (twisted trees, windmills, waterfalls, dunescapes, seascapes, winter landscapes, and panoramas, all with and without figures painted in by others).

His work was in demand in his home country during his lifetime, and afterwards in England as well, and today is spread across private and institutional collections globally, with the National Gallery in London, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg each holding more than a dozen of his creations. He paved the way for the Romantic style that came about in the late 18th century, and was influential for the Düsseldorf school of painting and Hudson River School in the 19th century.

Life

Little is known with certainty about Jacob Isaackszoon van Ruisdael.

He was born in Haarlem in 1628 or 1629[A] into a family of painters, all landscapists. The name Ruisdael is connected to a castle, now lost, in Blaricum, where Jacob's grandfather, furniture maker Jacob de Goyer, lived. When his grandfather moved away to Naarden, three of his sons changed their name into Ruysdael or Ruisdael, probably to indicate their origin.[2] While in modern Dutch the "uy" spelling is only preserved in names and the "ui" is dominant, before modern spelling regulations the "uy" was spelled interchangeably with "uij", with "ij" in combination just being another way to represent "y", and "ui" being shorthand for "uij".[B] Two of de Goyer's sons became painters: Jacob's father Isaack van Ruisdael and his uncle Salomon van Ruysdael. Jacob himself always spelled his name with an "i".[2] His cousin, Salomon's son Jacob Salomonsz van Ruysdael, also a landscape artist, spelled his name with a "y".[1] Jacob's earliest biographer, Arnold Houbraken, called him Jakob Ruisdaal, and claimed his name was formed from his specialty in waterfalls, namely the "ruis" (rustling noise of water) into a "daal" (dale) where it foams out into a pond or wider river. He went on to mention that the "ruis-daal" effect could also be used to describe his peculiar form of stormy sea paintings.[3]

The earliest date that appears on his paintings and etchings is 1646.[4] [C] Two years later he was admitted to membership of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke.

Around 1657 he moved to Amsterdam, most likely because its prosperity offered him a bigger audience. Fellow Haarlem painter Allaert van Everdingen had already moved to Amsterdam and created a market for their style. Ruisdael lived and worked in Amsterdam for the rest of his life.[5] In 1668 his name appears there as a witness to the marriage of Meindert Hobbema, his only registered pupil, whose works have also been confused with his own.[6]

For a landscape artist, it seemed he travelled relatively little: to Blaricum, Egmond aan Zee, and Rhenen in the 1640s, Bentheim and Steinfurt on the border with Germany with Nicolaas Berchem in 1650,[7] and possibly with Hobbema again to the German border in 1661, via de Veluwe, Deventer en Ootmarsum.[6] Despite his numerous Norwegian landscapes, there is no record of any trip to Scandinavia.

-

A View of Egmond aan Zee, by Isaack van Ruisdael

-

A View of Egmond aan Zee, by Salomon van Ruysdael

-

A View of Egmond aan Zee, by Jacob van Ruisdael

-

A Road through a Wood, by Cornelis Vroom

-

Road through an Oak Forest, by Jacob van Ruisdael

-

A View of Burg Bentheim, by Jacob van Ruisdael

-

A View of Burg Bentheim, by Nicolaas Berchem

-

Stormy Sea, by Jacob van Ruisdael

-

Three Damloopers in a Fresh Breeze, by Jan Porcellis

-

The Watermill, by Jacob van Ruisdael

-

A Watermill, by Meindert Hobbema

It is not certain if Ruisdael also was a doctor. In 1718 Houbraken reports that he studied medicine and performed surgery in Amsterdam.[8] Archival records of the 17th century show the name "Jacobus Ruijsdael" on a list of Amsterdam doctors, albeit crossed out, with the added remark that he earned his medical degree on 15 October 1676 in Caen, Northern France. Various art historians have speculated whether this is a case of mistaken identities. Scheltema claimed this was Ruisdael's cousin.[9] Ruisdael expert Seymour Slive argued that the spelling "uij" is unusual for Jacob, that his phenomenal production suggests there was little time to study medicine, and that there is no indication in any of his art that he visited Northern France. Slive concludes Ruisdael may or may not have been a doctor.[10] In 2013 Hinrich concludes as well that the evidence is inconclusive.[11]

Some have inferred from his two famous paintings of a Jewish cemetery that Ruisdael was Jewish, but there is no evidence to support this. He was in fact baptized on 14 June 1657 at the Calvinist Reformed Church in Amsterdam, and buried in the Saint Bavo's Church, Haarlem, also a Protestant church at that time.[12] His uncle Salomon van Ruysdael belonged to the Young Flemish subgroup of the Mennonite congregation, one of several types of Anabaptists in Haarlem, as probably did his father.[13]

Ruisdael was not married, according to Houbraken "to reserve time to serve his old father".[3]

Wijnman disproved the stubborn myth that Ruisdael died as a poor man, supposedly in the old men's almshouse in Haarlem. He proved that this in fact was Ruisdael's cousin, Jacob Isaackszoon.[14] Although there is no record of his owning land or shares, Ruisdael's paintings sold well and he was living comfortably, even after the economic downturn of the disaster year 1672. [D]

Ruisdael died in Amsterdam on 10 March 1682.[16] He was buried 14 March 1682 in the Saint Bavo's Church, Haarlem.[6]

Work

The early years

Ruisdael's teacher is not known. It is often assumed he first studied with his father and uncle, but there is no archival evidence for that, and his early works have been confused with theirs. He was strongly influenced by other contemporary Haarlem landscapists however, most notably Cornelis Vroom, who created atmospheric, detailed landscapes, Nicolaes Berchem, a friend with whom he travelled, Allaert van Everdingen, who created Nordic landscapes with waterfalls, and Roelant Roghman, who created popular dramatic castle themes on hillsides.[6]

Characteristic of his early period, from 1646 to early 1650s, while living in Haarlem, is the choice of simple motifs and the careful and laborious study of the details of nature: dunes, woods, fresh atmospheric effects, and, through heavier paint than his predecessors, foliage with a rich quality that give the sense of sap flowing through its branches and leaves.[17] His early sketches introduce motifs which return later: spaciousness, luminosity and an airy atmosphere achieved through pointillist-like touches of chalk.[18]

Exemplary of his style is Dune Landscape, one of his earliest works, dated 1646, which breaks with the classic Dutch tradition of depicting broad views of dunes that include houses and trees flanked by distant vistas. Instead, he prominently puts the dune with trees centre stage, with the cloudscape cleverly concentrating strong light on the sandy path.[18] The canvasses of his early work like this are remarkably large for an inexperienced painter.[19] As art historian Hofstede de Groot noted about Wooded Dune dated 1646, "it is hardly credible that it should be the work of a boy of seventeen".[20]

His first panoramic landscape dates from 1647, called View of Naarden. The theme of overwhelming sky and a distant town, in this case the birthplace of his father, is one he returned to in his later years.[18]

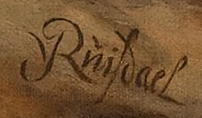

The year 1653 marks a salient point for art historians, as for reasons unknown, Ruisdael almost entirely stops dating his work. Only five works from the 1660s have a, partially obscured, year next to his signature; none from the 1670s and 1680s.[21] Dating subsequent work has therefore been largely detective work and speculation.[22]

The middle period

Following his travels, which helped him gain a broader view of nature and widened the horizon of his art, new monumental effects started to appear. A magnificent view of Bentheim Castle, dated 1654, is just one of a dozen of his depictions of this castle in Germany. The ruins of Egmont Castle near Alkmaar were another favourite subject and feature in The Jewish Cemetery, of which he painted two versions.[23] These versions show a characteristic polychronic lament for a stable past coupled with an unease for a profoundly unstable future. Ruisdael pits a rogue natural world against the built environment, which has been overrun by the trees and shrubs surrounding the cemetery.

Indisputable proof of Ruisdael's extraordinary creative power is offered by his Scandinavian waterfall paintings. He never went to Scandinavia, but fellow Haarlem painter van Everdingen had. He soon outstripped van Everdingen's finest efforts, in the end producing 160 works featuring waterfalls, of which Waterfall in a Mountainous Landscape with a Ruined Castle, c.1665–1670, is seen as his grandest.[24]

He started painting coastal scenes and sea-pieces, influenced by Cornelis Vroom, Simon de Vlieger and Jan Porcellis.[6] Among the most dramatic is Rough Sea at a Jetty, with a remarkably restricted palette of only black, white, blue and a few brown earth colours.[24] The prevailing hue of his landscapes is a full rich green, which, however, has darkened with time, while a clear grey tone is characteristic of his seascapes.

The later years

During his last period dominating mountain scenes appear, such as Mountainous and Wooded Landscape with a River, datable to the late 1670s, portraying a rugged range as lofty as the Alps, with the highest peak in the clouds.[25] By now, Ruisdael's subjects are uniquely varied, from his favourite woodland scenes, to waterfalls, dunes, beach scenes and seascapes, to panoramas of distant cities. Art historian Stechow identified 13 themes within the landscape genre and Ruisdael's work covers 11 of them, excelling at most.[26] [27]

Unsurprisingly, a typical Dutch landscape with windmill is one of his most famous works. Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, dated 1670, shows Wijk bij Duurstede, a riverside town about 20 kilometers from Utrecht, with a dominating cylindrical windmill, harmonised by the lines of river bank and sails, and the contrasts between light and shadow working together with the intensified concentration of mass and space.[25] Its enduring popularity is evidenced by card sales in the Rijksmuseum, with the Windmill ranking third after Rembrandt's Nightwatch and Vermeer's View of Delft.[22]

Various panoramic views of the Haarlem skyline and its bleaching grounds appear at this stage, with the clouds controlling the various gradations of alternating bands of light and shadow towards the horizon, often dominated by the St. Bavo Church, in which he would one day be buried.[25]

While the city of Amsterdam does feature in his work, it is relatively rare for someone who lived there for over 25 years.[28] It does feature in his only architectural subject known: an admirable interior of the New Church, as well as in views of the Dam, and his Panoramic View of the Amstel Looking towards Amsterdam.

Figures are sparingly introduced into his compositions, and are by now no longer of his own hand[E] but done by various artists, including his pupil Meindert Hobbema, Nicolaes Berchem, Adriaen van de Velde, Philip Wouwerman, Jan Vonck, Thomas de Keyser and Jan Lingelbach.[6]

Ruisdael etched a few plates, thirteen according to the latest catalogue raisonné by Slive, which he evidently regarded as experimental and somewhat private, to judge by their extreme rarity - about half survive in only a single impression (copy).[30] Many have very crowded compositions of foliage. The Cornfield and the Travellers are characterized by Duplessis as prints of a high order which may be regarded as the most significant expressions of landscape art in the Low Countries.

The art of Ruisdael, while it shows little of the scientific knowledge of later landscapists, is sensitive and poetic in sentiment, and direct and skilful in technique. Unlike the other great Dutch landscape painters, Ruisdael did not aim at a pictorial record of particular scenes, but carefully thought out and arranged his compositions, introducing into them an infinite variety of subtle contrasts in the formation of the clouds, the plants and tree forms, and the play of light.

Attributions

Slive attributes 694 paintings to Ruisdael and lists another 163 paintings with dubious or wrong attribution.[31] [F] Three main reasons are causing uncertainty of whose hand has painted various Ruisdael style landscapes. Firstly, four members of the Ruysdael family were landscapists. Secondly, many works from what is now called the Haarlem Landscape School of Painting were unsigned. The works that do have a signature typically read "JvRuisdael" or "JVR". Thirdly, it seemed that sometimes two artists would work together on one painting, not only one adding small figures to the landscapes of the other, but more prominent figures as well, such as in Cornelis de Graeff and his wife and sons arrive at their country house Soestdijk, complete with horses and carriage, currently attributed to Thomas de Keyser and Ruisdael. Unlike the large forensic science effort put into finding the correct attributions of Rembrandt's paintings, through the Rembrandt Research Project, there is no large scale systematic approach to ascertain Ruisdael's attributions.

Legacy

Ruisdael remained an esteemed artist after his death. A record from 1687 shows a merchant to possess a waterfall painting "in the style of Ruisdael". Houbraken tells of a certain Jan Griffier the Elder who could imitate Ruisdael's style so well that he often sold them for real Ruisdaels, especially with figurines added in the style of Philip Wouwerman.[33] His work shows some of the sensibilities the Romantics would later celebrate. Among the English artists influenced by Ruisdael are Thomas Gainsborough, J. M. W. Turner, and John Constable. Gainsborough drew, in black chalk and grey wash, a replica of a Ruisdael in the 1740s—now both in the Louvre in Paris.[34] "It haunts my mind and clings to my heart", wrote Constable after seeing a Ruisdael.[35]

In the 19th century he was an influence on the Düsseldorf School of Painting[36] and Hudson River School, for instance Thomas Doughty.[37] Vincent van Gogh acknowledged Ruisdael as a major influence, calling him sublime, but at the same time saying it would be a mistake trying to copy him.[38] He had two Ruisdael prints, The bush and The bleeching fields, up on his wall,[39] and thought the Ruisdaels in the Louvre were "magnificent, especially The bush, The breakwater and The ray of sunlight".[40] His experience of the French countryside was informed by his memory of Ruisdael's art.[41] Van Gogh's contemporary Claude Monet is also said to owe Ruisdael very much.[42] Even Piet Mondriaan's minimalism has been traced back to Ruisdael's panoramas.[42]

-

Landscape with Windmills near Haarlem by Jacob van Ruisdael 1651

-

Landscape with Windmills near Haarlem by John Constable 1830

-

The Ray of Light by Jacob van Ruisdael c.1665

-

Copy by Thomas Doughty c.1846

Among art critics, Ruisdael's reception has not much changed over the centuries. A first account, in 1718, is from Houbraken, who waxed lyrical over his technical mastery to realistically depict water in waterfalls and sea.[43] Soon after the English art critics began to sing his praises, but not all of them. In 1801, Henry Fuseli, professor at the Royal Academy, showed his contempt for the entire Dutch School of Landscape, dismissing it as no more than a "transcript of the spot", a mere "enumeration of hill and dale, clumps of trees".[44] Of note is that one of his students was Constable, whose admiration for Ruisdael remained unchanged.[45] Around that time in Germany, revered writer, statesman and scientist Goethe lauded him as a poet among painters, saying "he demonstrates remarkable skill in locating the exact point at which the creative faculty comes into contact with a lucid mind".[46] In 1911, Dutch art historian Bredius also called his compatriot not so much a painter as a poet.[47]

Modern-day critics also rate Ruisdael highly. Kenneth Clark called him "the greatest master of the natural vision before Constable".[48] Waldemar Januszczak finds him a marvellous storyteller. He does not rate him the greatest landscape artist of all time, but is especially impressed by his works as a teenager: "a prodigy whom we should rank at number 8 or 9 on the Mozart scale".[42] He is considered the most important member of the Haarlem Landscape School,[49] which is used to pinpoint a group of paintings that have retained their value over the centuries, not all of which can be attributed to a specific painter, but which can be attributed to a specific style (twisted trees, windmills, waterfalls, dunescapes, seascapes, winter landscapes, and panoramas, all with and without figures painted in by others).

Although many of his works were on show in the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester 1857, and various other grand exhibitions across the world subsequently, it was not until 1981 that an exhibition was solely dedicated to Ruisdael.[34]

Collections

Ruisdaels are scattered across collections globally, private and institutional. The most notable collections are at the National Gallery in London, which holds eighteen of his paintings;[17] the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which holds sixteen paintings;[50] and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, which holds eleven.[51] In the US, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has five paintings in its collection, the J. Paul Getty Museum in California three.

On occasion a Ruisdael changes hands. Most recently, in 2014, Dunes by the sea was auctioned at Christies in New York and realised a price of $1,805,000.[52]

Of his surviving drawings, a little over a hundred in total, the largest collection is at the Rijksmuseum print room in Amsterdam. The Hermitage possesses eight drawings, ranging in date from 1640s to 1670.[53]

Context

Ruisdael and his artworks should not be considered apart from the context of the incredible wealth and significant changes to the land that occurred during the Dutch Golden Age. In his landmark study on seventeenth century Dutch art and culture, Simon Schama remarks that "it can never be overemphasized that the period between 1550 and 1650, when the political identity of an independent Netherlands nation was being established, was also a time of dramatic physical alteration of its landscape."[54] Ruisdael's depiction of nature and emergent Dutch technology are wrapped up in this national anxiety.

Kuznetsov puts Ruisdael's art in the context of the independence war against Spain. Dutch landscape painters "were called upon to make a portrait of their homeland, twice rewon by the Dutch people - first from the sea and later from foreign invaders".[55]

Jonathan Israel, in his study of the Dutch Republic, states that the period between 1647 and 1672 coincides with the third phase of Dutch Golden Age art, in which the audience, consisting of wealthy merchants and cities, wanted large, opulent and refined paintings. For town halls there now was a demand for grand displays with a republican message.[56]

Some notable paintings

There is no consensus to use Template:Wikidata list in articles.

| Image | Title | Date | Collection | Inventory number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rough Sea at a Jetty | 1650s | Kimbell Art Museum | AP 1989.01 |

|

Bentheim Castle | 1650s | Rijksmuseum | SK-A-347 |

|

View of Egmond aan Zee | 1650 | Nationalmuseum | NM 618 |

|

Two Watermills and an Open Sluice near Singraven | 1650 | National Gallery | NG986 |

|

The watermill | 1660 | National Gallery of Victoria | 1249-3 |

|

The Jewish Cemetery | 1660 | Detroit Institute of Arts | 26.3 |

|

A Waterfall in a Rocky Landscape | 1660 | National Gallery | NG627 |

|

The Ray of Light | 1665 | Department of Paintings of the Louvre | INV 1820 |

|

A Landscape with a Ruined Castle and a Church | 1665 | National Gallery | NG990 |

|

A Wooded Marsh | 1665 1660s |

Hermitage Museum | 934 |

|

Landscape with Waterfall | 1668 | Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Museum |

SK-C-210 SA 8297 |

|

Winter Landscape near Haarlem | 1670s | Städel | 1109 |

|

View of Haarlem with bleaching fields | 1670 | Kunsthaus Zürich | |

|

The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede | 1670 | Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Museum |

SK-C-211 SA 8296 |

|

View on the Amstel from Amsteldijk | 1680 | Amsterdam Museum | SA 56435 |

Footnotes

- ^ This is inferred from a document dated 9 June 1661 in which Ruisdael states to be 32 years old.[1]

- ^ For a list of common spellings of the Ruisdael name over the centuries, see his ULAN entry.

- ^ It was unusual that signed and dated works for an artist were created before matriculation in a guild.

- ^ Tax records show Ruisdael paid 10 guilders for the 0.5% wealth tax in 1674, indicating his net worth was 2,000 guilders.[15]

- ^ In the past it was assumed that Ruisdael never painted figures himself. More recently though it is assumed that in his early years he did do it himself.[19] Landscape with Hut of 1646 is one such example.[29]

- ^ Hofstede de Groot felt the problem of attribution first hand in 1911, when catalog number 60 in his catalogue raisonné of Ruisdael was judged not to be authentic, causing a last minute footnote before going to press.[32]

References

Notes

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 19.

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 17.

- ^ a b Houbraken 1718.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f "Jacob van Ruisdael in the RKD". rkd.nl. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 4.

- ^ Houbraken 1718, p. 65.

- ^ Scheltema 1872, p. 95.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 19-20.

- ^ Hinrich 2013, pp. 58–62.

- ^ Wecker, Menachem (2005-10-21). "Jacob van Ruisdael Is Not Jewish". Forward. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Israel 1985, p. 397.

- ^ Wijnman 1932, p. 49-60;173-181;258-275.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 26.

- ^ Slive 1991, p. 598-606.

- ^ a b Slive 2006, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Slive 2006, p. 2.

- ^ a b Howard 1988, p. 63.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 275.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 6.

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 21.

- ^ Slive 2006, p. 3.

- ^ a b Slive 2006, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Slive 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Stechow 1966.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 16.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 29.

- ^ Slive 2001.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. contents.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 3.

- ^ Slive & Roetink 1981, p. 23.

- ^ a b Slive & Roetink 1981, p. 13.

- ^ Slive & Roetink 1981, p. 0.

- ^ Lenman, p. 68.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (2005-10-28). "Views of the Land Where the Dramatic Blues of the Sky Matter Most". New York Times. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Jansen; Luijten; Bakker (2009). "Van Gogh - the letters. Letter 249".

- ^ Jansen; Luijten; Bakker (2009). "Van Gogh - the letters. Letter 37".

- ^ Jansen; Luijten; Bakker (2009). "Van Gogh - the letters. Letter 34".

- ^ "In line with van Gogh". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Januszczak, Waldemar (26 February 2006). "Art: Jacob van Ruisdael". Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Houbraken 1718, p. 66.

- ^ Wornum 1848, p. 450.

- ^ "Jacob van Ruisdael". artble.com.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 0.

- ^ Bredius 1911, p. 3.

- ^ Clark 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Muller, p. 166.

- ^ "Collection Search: "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael"". Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 1-11.

- ^ "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael (Haarlem 1628/9-c. 1682 Amsterdam) Dunes by the sea". Christies. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 9.

- ^ Schama 1987, p. 34.

- ^ Kuznetsov, p. 3.

- ^ Israel 1995, p. 875.

Bibliography

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. Birmingham, Ala: Birmingham Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- Bredius, Abraham (1915), "Twee testamenten van Jacob van Ruisdael" [Two wills of Jacob van Ruisdael], Oud Holland, vol. XXXIII, no. 1, pp. 19–25

- Clark, Kenneth (1979). Landscape into art. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3610-6.

- Hinrichs, Jan Paul (2013), "Nogmaals over een oud raadsel - Jacob van Ruisdael, Arnold Houbraken en de Amsterdamse naamlijst van geneesheren" [Once more on the old riddle - Jacob van Ruisdael, Arnold Houbraken and the Amsterdam list of physicians], Oud Holland, vol. 126, no. 1

- Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis (1912). A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth century. Vol. 4. London: Macmillan.

- Houbraken, Arnold (1718). De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen [The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters] (in Dutch). Amsterdam: B.M. Israël. ISBN 978-90-6078-076-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic - its rise, greatness, and fall 1477–1806. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820734-4.

- Krugler, Franz Theodor (1846). A Hand-Book of the History of Painting ... Part II. The German, Flemish, and Dutch Schools of Painting. London: John Murray.

- Kuznetsov, Yuri (1983). Jacob van Ruisdael: Masters of world painting. Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8109-2280-8.

- Lenman, Robin (1997). Artists and Society in Germany, 1850–1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3636-1.

- Howard, Kathleen, ed. (1988). Dutch and Flemish Paintings from the Hermitage. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-509-5.

- Muller, Sheila (1997). Dutch Art: An Encyclopedia. Garland reference library of the humanities. Vol. 1021. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8153-0065-6.

- Schama, Simon (1987). The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. New York: Alfred Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-78124-0.

- Scheltema, P (1872), "Jacob van Ruijsdael", Aemstel's Oudheid IV

- Slive, Seymour; Hoetink, Hendrik Richard (1981). Jacob van Ruisdael. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-89659-226-1. OCLC 553087.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (1991), "Additions to Jacob van Ruisdael", Burlington Magazine, vol. 133, no. September, pp. 598–606

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (2001). Jacob van Ruisdael: A complete catalogue of his paintings, drawings, and etchings. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08972-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (2006). Jacob van Ruisdael, master of landscape. Royal Academy of Arts Gallery Guide 2006 exhibition.

- Slive, Seymour (2011). Jacob van Ruisdael: windmills and water mills. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-055-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stechow, Wolfgang (1966). Dutch landscape painting of the seventeenth century. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Walford, E. John (1991). Jacob Van Ruisdael and the Perception of Landscape. New Haven, London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300049947.

- Watson, Robert (2007). Back to nature: the green and the real in the late Renaissance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-2022-3.

- Wijnman, H.F. (1932), "Het leven der Ruysdaels" [The life of the Ruysdaels], Oud Holland, vol. XLIX

- Wornum, Ralph (1848). Lectures on painting: by the royal academicians, Barry, Opie and Fuseli. London: H. G. Bohn.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Ruisdael's biography, style and artworks

- The National Gallery: Jacob van Ruisdael

- Works and literature on Jacob van Ruisdael

- Dutch and Flemish paintings from the Hermitage, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Ruisdael (cat. no. 28-30)

- The BBC Your paintings: Jacob van Ruisdael

- Video: Vantage points of views of Haarlem (Haerlempjes) - St Bavo