Jacob van Ruisdael

Jacob van Ruisdael | |

|---|---|

Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede (c. 1670) | |

| Born | 1628 or 1629 |

| Died | 10 March 1682 Amsterdam, Dutch Republic |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | Landscape painting |

| Notable work | The Jewish Cemetery, Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, View of Haarlem with Bleaching Fields |

| Movement | Dutch Golden Age |

| Patron(s) | Cornelis de Graeff (1599–1664) |

Jacob Isaackszoon van Ruisdael (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈjaːkɔp vɑn ˈrœysdaːl] ; c. 1629 – 10 March 1682) was the pre-eminent Dutch Golden Age painter of landscapes. He was prolific and versatile, depicting a wide variety of landscape subjects.

Ruisdael has three family members who were also landscape painters, some of whom spelled their name "Ruysdael": his father Isaack van Ruisdael, his well-known uncle Salomon van Ruysdael, and his cousin, confusingly called Jacob van Ruysdael. Attributions among the family members, as well as a wider group of Haarlem landscape painters, are uncertain as not all works are signed and dated.

During his early phase, starting in 1646, Ruisdael predominantly painted Dutch countryside scenes of remarkable quality given his age. In the middle phase, after having travelled to Germany, his landscapes took on a more heroic character. In his final stage, while living and working in Amsterdam, he added city panoramas and seascapes to his regular repertoire, in which the sky often took up two thirds of the canvas. Waterfalls feature often in his oeuvre. His only documented pupil was Meindert Hobbema, one of several artists who painted figures in his landscapes.

His work was in demand in the Dutch Republic during his lifetime, and afterwards in England as well. Today it is spread across private and institutional collections globally, with the National Gallery in London, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg each holding more than a dozen of his creations. Ruisdael paved the way for the Romantic style of the late 18th century, and was influential for the Düsseldorf school of painting in the 19th century.

Life

Little is known with certainty about Jacob Isaackszoon van Ruisdael. He was born in Haarlem in 1628 or 1629[A] into a family of painters, all landscapists. The number of painters in the family, and multiple spellings of the Ruisdael name, have hampered attempts to document his life and attribute his works. The name Ruisdael is connected to a castle, now lost, in the village of Blaricum where Jacob's grandfather, furniture maker Jacob de Goyer, lived. When De Goyer moved away to Naarden, three of his sons changed their name into Ruysdael or Ruisdael, probably to indicate their origin.[2][B] Two of De Goyer's sons became painters: Jacob's father Isaack van Ruisdael and his uncle Salomon van Ruysdael. Jacob himself always spelled his name with an "i".[2] His cousin, Salomon's son Jacob Salomonszoon van Ruysdael, also a landscape artist, spelled his name with a "y".[1] Jacob's earliest biographer, Arnold Houbraken, called him Jakob Ruisdaal, and claimed the name resulted from his specialty in waterfalls, namely the "ruis" (rustling noise of water) falling into a "daal" (dale) where it foams out into a pond or wider river.[5]

The earliest date that appears on Ruisdael's paintings and etchings is 1646.[6][C] Two years later he was admitted to membership of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke.[8] By now landscape paintings were found as often as history paintings in households, whereas at the time of Ruisdael's birth history paintings were present twice as much. This growth in popularity of landscapes continued throughout his career.[9]

Around 1657, he moved to Amsterdam, most likely because its prosperity offered him a bigger audience. Fellow Haarlem painter Allaert van Everdingen had already moved to Amsterdam and created a market for their style. Ruisdael lived and worked in Amsterdam for the rest of his life.[10] In 1668, his name appears as a witness to the marriage of Meindert Hobbema, his only registered pupil, whose works have also been confused with his own.[11]

For a landscape artist, it seemed he travelled relatively little: to Blaricum, Egmond aan Zee, and Rhenen in the 1640s, Bentheim and Steinfurt just across the border with Germany with Nicolaas Berchem in 1650,[12] and possibly with Hobbema again across the German border in 1661, via the Veluwe, Deventer and Ootmarsum.[13] Despite his numerous Norwegian landscapes, there is no record of any trip to Scandinavia.[14]

It is unclear whether or not Ruisdael was also a doctor. In 1718, Houbraken reports that he studied medicine and performed surgery in Amsterdam.[5] Archival records of the 17th century show the name "Jacobus Ruijsdael" on a list of Amsterdam doctors, albeit crossed out, with the added remark that he earned his medical degree on 15 October 1676 in Caen, northern France.[15] Various art historians have speculated that this is a case of mistaken identity. Pieter Scheltema concluded it was Ruisdael's cousin who appeared.[16] Ruisdael expert Seymour Slive argued that the spelling "uij" is unusual for Jacob, that his unusually high production suggests there was little time to study medicine, and that there is no indication in any of his art that he visited northern France. Slive concluded Ruisdael may or may not have been a doctor.[15] In 2013, Jan Paul Hinrichs also decided that the evidence is inconclusive.[17]

Some have inferred from his two famous paintings of a Jewish cemetery that Ruisdael was Jewish, but once again there is no evidence to support this. He requested to be baptized at the Calvinist Reformed Church in Amsterdam, and was buried in the Saint Bavo's Church, Haarlem, also a Protestant church at that time.[18] His uncle Salomon van Ruysdael belonged to the Young Flemish subgroup of the Mennonite congregation, one of several types of Anabaptists in Haarlem, as probably did his father.[19] His cousin Jacob was a registered Mennonite in Amsterdam.[20]

Ruisdael did not marry, according to Houbraken "to reserve time to serve his old father".[21] It is not known what he looked like, as no portrait or self-portrait of him is known.[2][D]

Hendrik Frederik Wijnman disproved the stubborn myth that Ruisdael died as a poor man, supposedly in the old men's almshouse in Haarlem. He proved that the person who died there was in fact Ruisdael's cousin, Jacob Salomonszoon.[25] Although there is no record of him owning land or shares, Ruisdael lived comfortably, even after the economic downturn of the disaster year 1672. [E] His paintings were valued fairly highly. In 1664 a Ruisdael was valued the highest, 60 guilders, in an inventory including works by Willem van de Velde, Meindert Hobbema, and Jan van der Heyden.[27] Ruisdael died in Amsterdam on 10 March 1682. He was buried 14 March 1682 in Saint Bavo's Church, Haarlem.[28]

Work

Early years

Ruisdael's teacher is not known. It is often assumed he first studied with his father and uncle, but there is no archival evidence for this, and his early works have been confused with theirs.[29] He was strongly influenced by other contemporary Haarlem landscapists however, most notably Cornelis Vroom, who created atmospheric, detailed landscapes, Nicolaes Berchem, a friend with whom he travelled, Allaert van Everdingen, who created Scandinavian landscapes with waterfalls, and Roelant Roghman, who created popular dramatic castle themes on hillsides.[13]

Characteristic of his early period (c. 1646 to the early 1650s), while he was living in Haarlem, is the choice of simple motifs and the careful and laborious study of the details of nature: dunes, woods, fresh atmospheric effects, and through heavier paint than his predecessors, foliage with a rich quality that gives the sense of sap flowing through its branches and leaves.[30] His consistent accurate rendering of trees was unprecedented: the genera of his trees are the first to be unequivocally recognisable by modern-day botanists.[31] His early sketches introduce motifs that return later in all his work: spaciousness, luminosity and an airy atmosphere achieved through pointillist-like touches of chalk.[32]

An exemplar of his style is Dune Landscape, one of his earliest works, dated 1646, which breaks with the classic Dutch tradition of depicting broad views of dunes that include houses and trees flanked by distant vistas. Instead, he puts the dune with trees prominently centre stage, with the cloudscape concentrating strong light on the sandy path.[32] This heroic effect is enlarged by the large size of the canvas, "so unexpected in the work of an inexperienced painter" according to Irina Sokolova, curator at the Hermitage Museum.[33] As art historian Hofstede de Groot noted of Wooded Dune dated 1646, "it is hardly credible that it should be the work of a boy of seventeen".[34]

His first panoramic landscape dates from 1647, called View of Naarden. The theme of overwhelming sky and a distant town, in this case the birthplace of his father, is one he returned to in his later years.[32]

For unknown reasons, Ruisdael almost entirely stops dating his work from 1653. Only five works from the 1660s have a, partially obscured, year next to his signature; none from the 1670s and 1680s.[35] Dating subsequent work has therefore been largely based on detective work and speculation.[36]

All thirteen known Ruisdael etchings come from his early period, with the first one dated 1646. It is unknown who taught him the art of etching, as no etchings exist signed by his father, his uncle, or Cornelis Vroom. His etchings show little influence from Rembrandt, neither in style or technique. Few original impressions exist; five etchings survive in only a single impression. Slive states that the rarity of prints suggests that Ruisdael considered them trial essays that did not warrant large editions.[37] Etching expert Georges Duplessis singled out The Cornfield and The Travellers as unrivalled illustrations of his genius.[38]

Middle period

Following his trip into Germany, which helped him gain a broader view of nature, his landscapes took on a more heroic character, with forms becoming larger, more massive and weighty.[39] A view of Bentheim Castle, dated 1653, is just one of a dozen of his depictions of this castle in Germany, almost all of which show the castle on a hilltop. Significant are the numerous changes Ruisdael makes to the castle's setting, actually on an unimposing low hill, culminating in the 1653 version showing Bentheim Castle on a wooded mountain.[40] These variations are considered evidence of his compositional skills.[41][F] The ruins of Egmont Castle near Alkmaar were another favourite subject and feature in The Jewish Cemetery, of which he painted two versions.[39] In the painting Ruisdael pits the natural world against the built environment, which has been overrun by the trees and shrubs surrounding the cemetery.[43]

Ruisdael's first Scandinavian views, with big firs, rugged mountains, large boulders and rushing torrents, date from this period.[44] Though convincingly realistic, these paintings are based on art, not nature. There is no record of any trip to Scandinavia, but fellow Haarlem painter van Everdingen had travelled there in 1644 and had popularised the subgenre.[45] Ruisdael soon outstripped van Everdingen's finest efforts,[46] in the end producing more than 150 works featuring waterfalls,[14] of which Waterfall in a Mountainous Landscape with a Ruined Castle, c. 1665–1670, is seen as his grandest by Slive.[47]

Ruisdael started painting coastal scenes and sea-pieces, influenced by Cornelis Vroom, Simon de Vlieger and Jan Porcellis.[13] Among the most dramatic is Rough Sea at a Jetty, with a restricted palette of only black, white, blue and a few brown earth colours.[47]

Later years

During his last period mountain scenes appear, such as Mountainous and Wooded Landscape with a River, dateable to the late 1670s, portraying a rugged range as lofty as the Alps, with the highest peak in the clouds.[48] By now, Ruisdael's subjects are unusually varied, from his favourite woodland scenes, to waterfalls, dunes, beach scenes and seascapes, to panoramas of distant cities. Art historian Wolfgang Stechow identified 13 themes within the landscape genre and Ruisdael's work covers all but two of them, excelling at most. Only the Italianate and biblical landscapes are absent from his oeuvre.[49][50][G]

Unsurprisingly, a typical Dutch landscape with a windmill is one of Ruisdael's most famous works. Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede, dated 1670, shows Wijk bij Duurstede, a riverside town about 20 kilometers from Utrecht, with a dominant cylindrical windmill, harmonised by the lines of river bank and sails, with the contrasts between light and shadow working together with the intensified concentration of mass and space.[48] Its enduring popularity is evidenced by card sales in the Rijksmuseum, with the Windmill ranking third after Rembrandt's Night Watch and Vermeer's View of Delft.[36]

Various panoramic views of the Haarlem skyline and its bleaching grounds appear at this stage, a specific genre called Haerlempjes,[10] with the clouds controlling the various gradations of alternating bands of light and shadow towards the horizon, often dominated by the Saint Bavo's Church, in which Ruisdael would one day be buried.[48]

While Amsterdam does feature in his work, it does so relatively rarely for someone who lived there for over 25 years. It does feature in his only architectural subject known, an interior of the New Church, as well as in views of the Dam, and his Panoramic View of the Amstel Looking towards Amsterdam.[52]

Figures are sparingly introduced into his compositions, and are by this period no longer of his own hand[H] but executed by various artists, including his pupil Meindert Hobbema, Nicolaes Berchem, Adriaen van de Velde, Philips Wouwerman, Jan Vonck, Thomas de Keyser, Gerard van Battum and Jan Lingelbach.[13][54]

Attributions

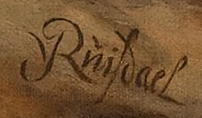

Slive attributes 694 paintings to Ruisdael and lists another 163 paintings with dubious or, he believes, incorrect attribution.[55] [I] There are three main reasons why there is uncertainty over whose hand has painted various Ruisdael-style landscapes. Firstly, four members of the Ruysdael family were landscapists with similar signatures, which have sometimes later fraudulently been altered into Jacob's,[57] which typically read "JvRuisdael" or "JVR".[13] Secondly, many 17th century landscape paintings are unsigned and could be from pupils or copyists.[58] Thirdly, fraudsters have imitated Ruisdaels for financial gain, with the earliest case known by 1718.[54] There is no large-scale systematic approach to ascertain Ruisdael's attributions, unlike the forensic science put into finding the correct attributions of Rembrandt's paintings, through the Rembrandt Research Project.[59]

Legacy

Ruisdael remained an esteemed artist after his death. A record from 1687 shows a merchant to possess a waterfall painting "in the style of Ruisdael". Houbraken mentions a certain Jan Griffier the Elder who could imitate Ruisdael's style so well that he often sold them for real Ruisdaels, especially with figurines added in the style of Philip Wouwerman.[54] Ruisdael's work shows some of the sensibilities the Romantics would later celebrate. Among the English artists influenced by Ruisdael are Thomas Gainsborough, J. M. W. Turner, and John Constable. Gainsborough drew, in black chalk and grey wash, a replica of a Ruisdael in the 1740s—now both in the Louvre in Paris.[60] Constable also copied various drawings, etchings and paintings of Ruisdael, and was a great admirer from a young age.[61] "It haunts my mind and clings to my heart", he wrote after seeing a Ruisdael.[62] But he thought the Jewish Cemetery was a failure, because it attempts to tell that which is outside the reach of art.[63]

In the 19th century Ruisdael was an influence on the Düsseldorf School of Painting.[64] Vincent van Gogh acknowledged Ruisdael as a major influence, calling him sublime, but at the same time saying it would be a mistake to try and copy him.[65] He had two Ruisdael prints, The Bush and The Bleeching Fields, up on his wall,[66] and thought the Ruisdaels in the Louvre were "magnificent, especially The Bush, The Breakwater and The Ray of Sunlight".[67] His experience of the French countryside was informed by his memory of Ruisdael's art.[68] Van Gogh's contemporary Claude Monet is also said to owe Ruisdael very much.[69] Even Piet Mondriaan's minimalism has been traced back to Ruisdael's panoramas.[69]

Among art historians, Ruisdael's reputation has not changed much over the centuries. The first account, in 1718, is from Houbraken, who waxed lyrical over the technical mastery which allowed him to realistically depict water in waterfalls and the sea.[70] Soon afterwards English art critics began to sing his praises, but not all of them. In 1801, Henry Fuseli, professor at the Royal Academy, expressed his contempt for the entire Dutch School of Landscape, dismissing it as no more than a "transcript of the spot", a mere "enumeration of hill and dale, clumps of trees".[71] Of note is that one of Fuseli's students was Constable, whose admiration for Ruisdael remained unchanged.[61] Around the same time in Germany, the writer, statesman and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe lauded Ruisdael as a poet among painters, saying "he demonstrates remarkable skill in locating the exact point at which the creative faculty comes into contact with a lucid mind".[72] In 1915, Dutch art historian Abraham Bredius also called his compatriot not so much a painter as a poet.[73]

Modern art historians also rate Ruisdael highly. Kenneth Clark described him as "the greatest master of the natural vision before Constable".[74] Waldemar Januszczak finds him a marvellous storyteller. He does not rate Ruisdael the greatest landscape artist of all time, but is especially impressed by his works as a teenager: "a prodigy whom we should rank at number 8 or 9 on the Mozart scale".[69] Slive states he is acknowledged "by general consent, as the pre-eminent landscapist of the Golden Age of Dutch art".[30]

"Ruisdael really doesn’t deserve to be underrated. ..[H]e was a prodigy whom we should rank at number 8 or 9 on the Mozart scale."

— The Guardian art critic Waldemar Januszczak[69]

Ruisdael is now seen as the leading artist of the "classical" phase in Dutch landscape art, which builds upon the realism of the previous "tonal" phase. The tonal phase suggested atmosphere through the use of tonality. The classical phase strived for a more grandiose effect. The pictures are built up in vigorous contrasts of solid form against the sky, of light against shade, often singling out a tree, animal, or windmill.[75]

Although many of Ruisdael's works were on show in the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester 1857, and various other grand exhibitions across the world subsequently, it was not until 1981 that an exhibition was solely dedicated to Ruisdael. Over fifty paintings and thirtyfive drawings and etchings were exhibited, first at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, then, in 1982, at the Fogg Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[60] In 2006, the Royal Academy in London hosted a Ruisdael Master of Landscape exhibition, displaying works from over fifty collections.[76]

Interpretation

There are no 17th century documents to indicate, either at first or second hand, what Ruisdael intended to convey through his art.[2] Records of how scholars have interpreted his landscapes date from the 18th century. While the The Jewish Cemetery is universally accepted as an allegory for the fragility of life,[63] [77] [78] how other works should be interpreted is much disputed. At one end of the spectrum is Royal Academy professor Henry Fuseli, saying they have no meaning at all, and are simply a depiction of nature.[71] At the other end is Franz Theodor Kugler who sees meaning in almost everything: "They all display the silent power of Nature, who opposes with her mighty hand the petty activity of man, and with a solemn warning as it were, repels his encroachments".[79]

In the middle of the spectrum are scholars such as E. John Walford who sees the works as "not so much bearers of narrative or emblematic meanings but rather as images reflecting the fact that the visible world was essentially perceived as manifesting inherent spiritual significance".[80] Walford advocates abandoning the notion of 'disguised symbolism'.[81] All of Ruisdael's work can be interpreted according to the religious world view of his time: nature serves as the 'first book' of God, both because of its inherent divine qualities and because of God's obvious concern for man and the world. The interpretation is spiritual, not moral.[82]

Ruisdael's oeuvre is laden with looming clouds, dead trees, the play of light and shadow, and other elements that are easy to identify as spiritual or moral symbols. Andrew Graham-Dixon says all Dutch Golden Age landscapists could not help but search everywhere for meaning. He says of the windmill in The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede that it symbolises "the sheer hard work needed to keep Holland above water and to safeguard the future of the nation's children". The symmetries in the landscapes are "reminders to fellow citizens always to remain on the straight and narrow".[83] Seymour Slive is more reluctant to read too much into the work, but does put The Windmill in its contemporary religious context of man's dependence on the "spirit of the Lord for life".[84] With regards to interpreting Ruisdael's Scandinavian paintings, he says "My own view is that it strains credulity to the breaking point to propose that he himself conceived of all his depictions of waterfalls, torrents and rushing streams and dead trees as visual sermons on the themes of transcience and vanitas".[44]

Collections

Ruisdaels are scattered across collections globally, private and institutional. The most notable collections are at the National Gallery in London, which holds twenty of his paintings;[85] the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which holds sixteen paintings;[86] and the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, which holds nine.[87] In the US, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has five paintings in its collection,[88] the J. Paul Getty Museum in California three.[89]

On occasion a Ruisdael changes hands. Most recently, in 2014, Dunes by the Sea was auctioned at Christie's in New York and realised a price of $1,805,000.[90]

Of his surviving drawings, a 140 in total,[91] the largest collection is at the Rijksmuseum print room in Amsterdam. The Hermitage possesses eight drawings, ranging in date from the 1640s to 1670.[92]

Context

Ruisdael and his artworks should not be considered apart from the context of the incredible wealth and significant changes to the land that occurred during the Dutch Golden Age. In his landmark study on 17th-century Dutch art and culture, Simon Schama remarks that "it can never be overemphasized that the period between 1550 and 1650, when the political identity of an independent Netherlands nation was being established, was also a time of dramatic physical alteration of its landscape".[93] Ruisdael's depiction of nature and emergent Dutch technology are wrapped up in this.[93] Christopher Joby puts Ruisdael in the religious context of Calvinism in the Dutch Republic. "Landscape painting does conform to Calvin's requirement that only what is visible may be depicted in art, and stated that landscape paintings such as those of Ruisdael have an epistemological value which provides further support for their use within Reformed Churches".[94]

Yuri Kuznetsov places Ruisdael's art in the context of the war of independence against Spain. Dutch landscape painters "were called upon to make a portrait of their homeland, twice rewon by the Dutch people - first from the sea and later from foreign invaders".[95] Jonathan Israel, in his study of the Dutch Republic, calls the period between 1647 and 1672 the third phase of Dutch Golden Age art, in which wealthy merchants wanted large, opulent and refined paintings, and civic leaders filled their town halls with grand displays containing republican messages.[96]

In addition, ordinary middle class Dutch people began buying art for the first time, creating a high demand for paintings of all kinds.[97] This demand was met by enormous painter guilds.[98][J] Master painters set up studios to produce large numbers of paintings quickly.[K] Under the master's direction, studio members would specialise in parts of a painting, such as figures in landscapes or costumes in portraits and history paintings.[103][L] Numerous art dealers organised commissions on behalf of patrons, as well as buying uncommissioned stock to sell on.[104] Landscape artists did not depend on commissions in the way most painters had to do,[105] and could therefore paint for stock. However, in Ruisdael’s case, it is not known whether he kept stock to sell directly to customers, or sold his work through dealers, or both.[106] Art historians only know of one commission, a work for the wealthy Amsterdam burgomaster Cornelis de Graeff, jointly painted with Thomas de Keyser.[106] [M]

Footnotes

- ^ This is inferred from a document dated 9 June 1661 in which Ruisdael states to be 32 years old.[1]

- ^ While in modern Dutch the "uy" spelling is only preserved in names and the "ui" is dominant, before modern spelling regulations the "uy" was spelled interchangeably with "uij", with "ij" in combination just being another way to represent "y", and "ui" being shorthand for "uij".[3] The long list of common spellings of the Ruisdael name over the centuries includes "uy", "uij", and "ui".[4]

- ^ It was unusual that signed and dated works of an artist were created before matriculation in a guild.[7]

- ^ The Dutch coffee and tea company De Zuid-Hollandsche Koffie- en Theehandel published picture books in the 1920s with portraits of famous figures from Dutch history and the 1926 edition showed a portrait of "Jacob Isaaksz. Ruisdael" (sic).[22] It is not known where the coffee and tea company got the image from. Two 19th century sculptures, one on the outside wall of the Hamburger Kunsthalle built in 1863,[23] and one inside the Louvre made by Louis-Denis Caillouette in 1822,[24] are also not traceable back to a source.

- ^ Tax records show Ruisdael paid 10 guilders for the 0.5% wealth tax in 1674, indicating his net worth was 2,000 guilders.[26]

- ^ Other evidence of his compositional skills includes the botanically accurate representation of the shrub Viburnum lantana L. on the 1653 View of Bentheim Castle painting, for which there is no evidence of ever have been present in this area.[42]

- ^ Slive attributes the four untraceable references to biblical Ruisdaels to his uncle or cousin.[51]

- ^ In the past it was assumed that Ruisdael never painted figures himself. More recently though it is assumed that in his early years he did do so himself.[33] Landscape with Hut of 1646 is one such example.[53]

- ^ Hofstede de Groot felt the problem of attribution first hand in 1911, when catalog number 60 in his catalogue raisonné of Ruisdael was judged not to be authentic, causing a last minute footnote before going to press.[56]

- ^ Based on records of membership of the Guild of Saint Luke, it is estimated there was one painter for every 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants, compared to every 10,000 in Renaissance Italy.[99] A total of five million paintings were produced in the Dutch Republic in the 17th century.[98] Slive says there were hundreds of landscapists during Ruisdael's time.[100]

- ^ Studios already existed before Ruisdael was born.[101] Painters from the tonal phase had in addition developed efficient techniques such as wet-into-wet paint, but this did not work for the classical phase painters, which required a high level of realism.[102]

- ^ It is not certain if Ruisdael had more pupils other than Hobbema in his studio, but at least four other artists have been identified as having provided staffage for his landscapes.[13]

- ^ This work, The arrival of Cornelis de Graeff and Members of His Family at Soestdijk (c. 1660), is unusual in Ruisdael's oeuvre for another reason. It also is the only one in which his landscape is the background in the work of a portrait painter.[107]

References

Notes

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 17.

- ^ Reenen & Wijnands 1993, p. 389-419.

- ^ "Union list of artist names". Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ a b Houbraken 1718, p. 65.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 20.

- ^ Slive 2011, p. xi.

- ^ Jager 2015, p. 9.

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 22.

- ^ Wheelock, Arthur (24 April 2014). "Meindert Hobbema". nga.gov.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f "Jacob van Ruisdael in the RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History)". rkd.nl. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ a b Slive 2001, p. 153.

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 19-20.

- ^ Scheltema 1872, p. 105.

- ^ Hinrichs 2013, pp. 58–62.

- ^ Wecker, Menachem (21 October 2005). "Jacob van Ruisdael is not Jewish". Forward. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Israel 1995, p. 397.

- ^ Scheltema 1872, p. 101.

- ^ Houbraken 1718.

- ^ "Plaatjesalbum: De Zuid-Hollandsche Koffie- en Theehandel, Vaderlandsche historie". Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "Kunsthalle - Statues and portraits of artists".

- ^ Clarac 1841, p. 540.

- ^ Wijnman 1932, p. 49-60.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 26.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 25-26.

- ^ Slive 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ Slive 2005, p. 2,260.

- ^ a b Slive 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Ashton, Davies & Slive 1982, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Slive 2006, p. 2.

- ^ a b Sokolova 1988, p. 63.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 275.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 6.

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 21.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 591-593.

- ^ Duplessis 1871, p. 109.

- ^ a b Slive 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 52.

- ^ Ham 1983, p. 207.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 68.

- ^ a b Slive 2001, p. 154.

- ^ Slive 1982, p. 29.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 2.

- ^ a b Slive 2006, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Slive 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Stechow 1966.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 16.

- ^ Slive 1982, p. 28.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 11-22.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 23.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. contents.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 3.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 4.

- ^ Hofstede de Groot 1911, p. 6.

- ^ Wetering 2014, p. ix.

- ^ a b Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 13.

- ^ a b Slive 2001, p. 695-696.

- ^ Slive 2001, p. 695.

- ^ a b Slive 2001, p. 181.

- ^ Lenman 1997, p. 68.

- ^ Jansen, Luijten & Bakker 2009, Letter 249.

- ^ Jansen, Luijten & Bakker 2009, Letter 37.

- ^ Jansen, Luijten & Bakker 2009, Letter 34.

- ^ "In line with van Gogh". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Januszczak, Waldemar (26 February 2006). "Art: Jacob van Ruisdael". Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Houbraken 1718, p. 66.

- ^ a b Wornum 1848, p. 450.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 0.

- ^ Bredius 1915, p. 19.

- ^ Clark 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Slive 1995, p. 195.

- ^ Slive 2006.

- ^ Smith 1835, p. 4.

- ^ Rosenberg 1928, p. 30.

- ^ Krugler 1846, p. 338.

- ^ Walford 1991, p. 29.

- ^ Walford 1991, p. 201.

- ^ Bakker & Webb 2012, p. 212-213.

- ^ Graham-Dixon 2013.

- ^ Slive 2011, p. 28.

- ^ "Collection Search: "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael"". National Gallery. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Collection Search: "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael"". Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Collection Search: "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael"". Hermitage. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Collection Search: "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael"". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Collection Search: "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael"". J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael (Haarlem 1628/9-c. 1682 Amsterdam) Dunes by the sea". Christies. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Slive 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 9.

- ^ a b Schama 1987, p. 34.

- ^ Joby 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Kuznetsov 1983, p. 3.

- ^ Israel 1995, p. 875.

- ^ North 1997, p. 134.

- ^ a b Price 2011, p. 104.

- ^ North 1997, p. 79.

- ^ Slive 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Gifford 1995, p. 141.

- ^ Gifford 1995, p. 145.

- ^ Miedema 1994, p. 126.

- ^ North 1997, p. 93-95.

- ^ Montias 1989, p. 181.

- ^ a b Slive 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Slive & Hoetink 1981, p. 25.

Bibliography

- Ashton, Peter Shaw; Davies, Alice I.; Slive, Seymour (1982). "Jacob van Ruisdael's trees". Arnoldia. 42 (1): 2–31.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bakker, Boudewijn; Webb, Diane (2012). Landscape and Religion from Van Eyck to Rembrandt. Farnham, the U.K.: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-0486-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bredius, Abraham (1915). "Twee testamenten van Jacob van Ruisdael" [Two wills of Jacob van Ruisdael]. Oud Holland (in Dutch). 33 (1): 19–25.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clarac, Frédéric (1841). Musée de sculpture antique et moderne, ou description historique et graphique du Louvre [Museum of classic and modern sculptures, or historical and visual description of the Louvre] (in French). Paris: L'Imprimerie Royale. OCLC 656569988.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clark, Kenneth (1979). Landscape into Art. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3610-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duplessis, Georges (1871). The Wonders of Engraving. London: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston. OCLC 699616022.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graham-Dixon, Andrew (30 December 2013). "Boom and bust". The high art of the Low Countries. British Broadcast Corporation.

{{cite episode}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ham, R.W.J.M. van der (1983). "Is Viburnum lantana L. indigeen in de duinen bij Haarlem?" [Is Viburnum lantana L. indigenous in the Haarlem dunes?]. Gorteria (in Dutch). 11 (9): 206–207.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hinrichs, Jan Paul (2013). "Nogmaals over een oud raadsel: Jacob van Ruisdael, Arnold Houbraken en de Amsterdamse naamlijst van geneesheren" [Once more on the old riddle: Jacob van Ruisdael, Arnold Houbraken and the Amsterdam list of physicians]. Oud Holland (in Dutch). 126 (1): 58–62.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gifford, E. Melanie (1995). "Style and Technique in Dutch Landscape Painting in the 1620s". In Wallert, Arie; Hermens, Erma; Peek, Marja (eds.). Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-322-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis (1911). Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten Holländischen Mahler des XVII. Jahrhunderts [A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century] (in German). Vol. 4. Esslingen, Germany: Paul Neff. OCLC 2923803.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Houbraken, Arnold (1718). De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen deel 3 [The great theatre of Dutch painters part 3] (in Dutch). Amsterdam: B.M. Israël. ISBN 978-90-6078-076-3. OCLC 1081194.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic. Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820734-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jager, Angela (2015). ""Everywhere illustrious histories that are a dime a dozen": The Mass Market for History Painting in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam" (PDF). Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art. 7 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jansen, Leo; Luijten, Hans; Bakker, Nienke (2009). Vincent van Gogh – the Letters: the Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-23865-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Joby, Christopher (2007). Calvinism and the Arts: a Re-assessment. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1923-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Krugler, Franz Theodor (1846). A Hand-book of the History of Painting. Part II. The German, Flemish, and Dutch Schools of Painting. London: John Murray.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kuznetsov, Yuri (1983). Jacob van Ruisdael. Masters of World Painting. Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8109-2280-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lenman, Robin (1997). Artists and Society in Germany, 1850–1914. Manchester, the U.K.: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3636-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miedema, Hessel (1994). "The Appreciation of Paintings around 1600". In Luijten, Ger; Suchtelen, Ariane van (eds.). Dawn of the Golden Age Northern Netherlandish Art 1580 - 1620. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06016-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Montias, John Michael (1989). Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History. Princeton, N. Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04051-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - North, Michael (1997). Art and Commerce in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univeristy Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05894-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Price, J. Leslie (2011). Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-800-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reenen, Pieter van; Wijnands, Astrid (1993). "Early diphthongizations of palatalized West Germanic [ui] – the spelling uy in Middle Dutch". In Aertsen, Henk; Jeffers, Robert (eds.). Historical Linguistics 1989. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 978-1-55619-560-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosenberg, Jakob (1928). Jacob van Ruisdael. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer. OCLC 217274833.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schama, Simon (1987). The Embarrassment of Riches: an Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. New York: Alfred Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-78124-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scheltema, Pieter (1872). "Jacob van Ruijsdael". Aemstel's oudheid of gedenkwaardigheden van Amsterdam deel 6 [Aemstel's past or memorable facts of Amsterdam part 6] (PDF) (in Dutch). Amsterdam: C.L. Brinkman. OCLC 156222591.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour; Hoetink, Hendrik Richard (1981). Jacob van Ruisdael (Dutch ed.). Amsterdam: Meulenhoff/Landshoff. ISBN 978-90-290-8471-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (1982). "Jacob van Ruisdael". Harvard Magazine. 84 (3): 26–31.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (1995). Dutch Painting. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07451-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (2001). Jacob van Ruisdael: a Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Drawings, and Etchings. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08972-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (2005). Jacob van Ruisdael: Master of Landscape. London: Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 978-1-903973-24-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (2006). Jacob van Ruisdael. Gallery guide to the exhibition. Jacob van Ruisdael, master of landscape exhibition (25 February - 4 June 2006). London: Royal Academy of Arts.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Slive, Seymour (2011). Jacob van Ruisdael: Windmills and Water Mills. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-055-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, John (1835). A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters. Vol. 6. London: Sands. OCLC 3300061.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sokolova, Irina (1988). "Dutch paintings of the Seventeenth Century". In Howard, Kathleen (ed.). Dutch and Flemish Paintings from the Hermitage. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-509-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stechow, Wolfgang (1966). Dutch Landscape Painting of the Seventeenth Century. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-1330-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walford, E. John (1991). Jacob van Ruisdael and the Perception of Landscape. New Haven, Conn./London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04994-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wetering, Ernst van de (2014). A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings VI: Rembrandt's Paintings Revisited – A Complete Survey: 6 (Rembrandt Research Project Foundation). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. ISBN 978-94-017-9173-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wijnman, Hendrik (1932). "Het leven der Ruysdaels" [The life of the Ruysdaels]. Oud Holland (in Dutch). 49 (1): 49–60.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wornum, Ralph (1848). Lectures on Painting: by the Royal Academicians, Barry, Opie and Fuseli. London: H. G. Bohn. OCLC 7222842.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Media related to Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jacob Isaacksz. van Ruisdael at Wikimedia Commons