Endosperm

Endosperm is a tissue produced inside the seeds of most of the flowering plants around the time of fertilization. It surrounds the embryo and provides nutrition in the form of starch, though it can also contain oils and protein. This can make endosperm a source of nutrition in human diet. For example, wheat endosperm is ground into flour for bread (the rest of the grain is included as well in whole wheat flour), while barley endosperm is the main source for beer production. Other examples of endosperm that forms the bulk of the edible portion are coconut "meat" and coconut "water",[1] and corn. Some plants, like the orchid, lack endosperm in their seeds.

Origin of endosperm

Ancestral flowering plants have seeds that have small embryos and abundant endosperm, and the evolutionary development of flowering plants tends to show a trend towards plants with mature seeds with little or no endosperm. In more derived flowering plants the embryo occupies most of the seed and the endosperm is non developed or consumed before the seed matures.[2][3]

Double fertilization

Endosperm is formed when the two sperm nuclei inside a pollen grain reach the interior of an embryo sac or female gametophyte. One sperm nucleus fertilizes the egg, forming a zygote, while the other sperm nucleus usually fuses with the two polar nuclei at the center of the embryo sac, forming a primary endosperm cell (its nucleus is often called the triple fusion nucleus).That cell created in the process of double fertilization develops into the endosperm. Because it is formed by a separate fertilization, the endosperm constitutes an organism separate from the growing embryo.

About 70% of angiosperm species have endosperm cells that are polyploid.[4] These are typically triploid (containing three sets of chromosomes) but can vary widely from diploid (2n) to 15n.[5]

One species of flowering plant, Nuphar polysepala, has endosperm that is diploid, resulting from the fusion of a pollen nucleus with one, rather than two, maternal nuclei. It is believed that early in the development of angiosperm lineages, there was a duplication in this mode of reproduction, producing seven-celled/eight-nucleate female gametophytes, and triploid endosperms with a 2:1 maternal to paternal genome ratio.[6]

Endosperm formation

There are three types of Endosperm development:

Nuclear endosperm formation - where repeated free-nuclear divisions take place; if a cell wall is formed it will form after free-nuclear divisions. Commonly referred to as liquid endosperm. Coconut water is an example of this.

Cellular endosperm formation - where a cell-wall formation is coincident with nuclear divisions. Coconut meat is cellular endosperm. Acoraceae has cellular endosperm development while other monocots are helobial.

Helobial endosperm formation - Where a cell wall is laid down between the first two nuclei, after which one half develops endosperm along the cellular pattern and the other half along the nuclear pattern.

Evolutionary origins

The evolutionary origins of double fertilization and endosperm are unclear, attracting researcher attention for over a century of research. There are the two major hypothesis:[7]

- The double fertilization initially used to produce two identical, independent embryos ("twins"). Later these embryos acquired different roles, one growing into mature organism and another merely supporting it. Hence the early endosperm was probably diploid, same as another embryo. Some gymnosperms, such as Ephedra_(genus), may produce twin embryos by double fertilization. Any of these two embryos are capable of filling in the seed but normally only one develops further (the other eventually aborts). Also, most basal angiosperms still contain the four-cell embryo sac and produce diploid endosperms.

- Endosperm is the evolutionary remnant of the actual gametophyte, similar to the complex multicelular gametophytes found in gymnosperms. In this case, acquisition of the additional nucleus from the sperm cell is a later evolutionary step. This nucleus may provide the parental (not only maternal) organism with some control over endosperm development. Becoming triploid or polyploid are later evolutionary steps of this "primary gametophyte". Nonflowering seed plants (conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, Ephedra) form a large homozygous female gametophyte to nourish the embryo within a seed.[8]

The role of endosperm in seed development

In some groups (e.g. grains of the family Poaceae) the endosperm persists to the mature seed stage as a storage tissue, in which case the seeds are called "albuminous" or "endospermous", and in others it is absorbed during embryo development (e.g., most members of the family Fabaceae, including the common bean, Phaseolus vulgaris), in which case the seeds are called "exalbuminous" or "cotyledonous" and the function of storage tissue is performed by enlarged cotyledons ("seed leaves"). In certain species (e.g. corn, Zea mays); the storage function is distributed between both endosperm and the embryo. Some mature endosperm tissues store fats (e.g. castor bean, Ricinis communis) and others (including grains, such as wheat and corn) store mainly starches.

The dust-like seeds of orchids have no endosperm. Orchid seedlings are mycoheterotrophic in their early development. In some other species, such as coffee, the endosperm also does not develop.[9] Instead the nucellus produces a nutritive tissue termed "perisperm". The endosperm of some species is responsible for seed dormancy.[10] Endosperm also mediates the transfer of nutrients from the mother plant to the embryo, it acts as a location for gene imprinting, and is responsible for aborting seeds produced from genetically mismatched parents.[4] In angiosperms, the endosperm contain hormones such as cytokinins, which regulate cellular differentiation and embryonic organ formation.[11]

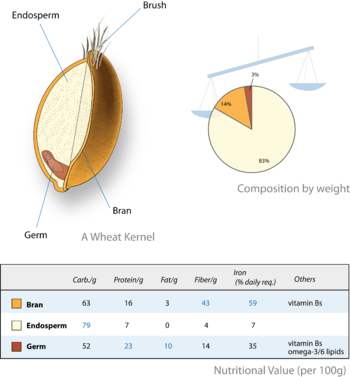

Cereal grains

Cereal crops are grown for their palatable fruit (grains or caryopses), which are primarily endosperm. In the caryopsis, the thin fruit wall is fused to the seed coat. Therefore, the nutritious part of the grain is the seed and its endosperm. In some cases (e.g. wheat, rice) the endosperm is selectively retained in food processing (commonly called white flour), and the embryo (germ) and seed coat (bran) removed. Endosperm thus has an important role within the human diet worldwide.

The aleurone is a maternal tissue that is retained as part of the seed in many small grains. The aleurone functions for both storage and digestion. During germination it secretes the amylase enzyme that breaks down endosperm starch into sugars to nourish the growing seedling.[12]

See also

References

- ^ retrieved 14 July 2010

- ^ "The Seed Biology Place - Seed Dormancy". Seedbiology.de. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- ^ Friedman, William E. (1998), "The evolution of double fertilization and endosperm: an "historical" perspective", Sexual Plant Reproduction, 11: 6, doi:10.1007/s004970050114

- ^ a b Olsen, By Odd-Arne (2007), "Endosperm: Developmental and Molecular Biology", ISBN 3-540-71234-8

- ^ "Figure 1". genomebiology.com. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-9-reviews1026. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Friedman, William E.; Williams, JH (2003), "Modularity of the Angiosperm Female Gametophyte and Its Bearing on the Early Evolution of Endosperm in Flowering Plants", Evolution, 57 (2): 216–30, doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00257.x, PMID 12683519

- ^ Célia Baroux, Charles Spillane, Ueli Grossniklaus (2002). Evolutionary origins of the endosperm in flowering plants. Genome Biol. 3(9)

- ^ [Friedman WE (1995)] Organismal duplication, inclusive fitness theory, and altruism: understanding the evolution of endosperm and the angiosperm reproductive syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Apr 25;92(9):3913-7.PMID 11607532pdf

- ^ Houk, W. G. (1938). "Endosperm and Perisperm of Coffee with Notes on the Morphology of the Ovule and Seed Development". American Journal of Botany. 25 (1): 56–61. doi:10.2307/2436631.

- ^ Mechanisms of plant growth and improved productivity: modern approaches edited by Amarjit S. Basra 1994. ISBN 0-8247-9192-4 p.

- ^ Pearson, Lorentz C. (1995), The diversity and evolution of plants, Boca Raton: CRC Press, p. 547, ISBN 0-8493-2483-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Endosperm Development. URL accessed on April 29, 2006.

External links

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.