Parachute

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag, or in the case of ram-air parachutes, aerodynamic lift. Parachutes are usually made out of light, strong cloth, originally silk, now most commonly nylon. Depending on the situation, parachutes are used with a variety of loads, including people, food, equipment, space capsules, and bombs.

Drogue chutes are used to aid horizontal deceleration of a vehicle (a fixed-wing aircraft, or a drag racer), or to provide stability (certain types of light aircraft in distress;[1][2] tandem free-fall).

Early Renaissance

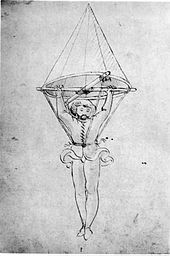

The earliest evidence for the parachute dates back to the Renaissance period.[3] The oldest parachute design appears in an anonymous manuscript from 1470s Renaissance Italy (British Museum Add. MSS 34,113, fol. 200v), showing a free-hanging man clutching a cross bar frame attached to a conical canopy.[4] As a safety measure, four straps run from the ends of the rods to a waist belt. The design is a marked improvement over another folio (189v), which depicts a man trying to break the force of his fall by the means of two long cloth streamers fastened to two bars which he grips with his hands.[5] Although the surface area of the parachute design appears to be too small to offer effective resistance to the friction of the air and the wooden base-frame is superfluous and potentially harmful, the revolutionary character of the new concept is obvious.[5]

Shortly after, a more sophisticated parachute was sketched by the polymath Leonardo da Vinci in his Codex Atlanticus (fol. 381v) dated to ca. 1485.[4] Here, the scale of the parachute is in a more favorable proportion to the weight of the jumper. Leonardo's canopy was held open by a square wooden frame, which alters the shape of the parachute from conical to pyramidal.[5] It is not known whether the Italian inventor was influenced by the earlier design, but he may have learned about the idea through the intensive oral communication among artist-engineers of the time.[6] The feasibility of Leonardo's pyramidal design was successfully tested in 2000 by Briton Adrian Nicholas and again in 2008 by Luigi Cani.[7] According to the historian of technology Lynn White, these conical and pyramidal designs, much more elaborate than early artistic jumps with rigid parasols in Asia, mark the origin of "the parachute as we know it."[3]

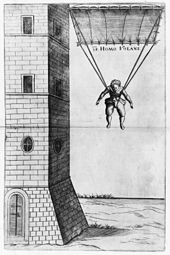

The Croatian inventor Faust Vrančić (1551–1617) examined da Vinci's parachute sketch, and set out to implement one of his own. He kept the square frame, but replaced the canopy with a bulging sail-like piece of cloth that he came to realize decelerates the fall more effectively.[5] A now-famous depiction of a parachute that he dubbed Homo Volans (Flying Man), showing a man parachuting from a tower, presumably St Mark's Campanile in Venice, appeared in his book on mechanics, Machinae Novae (1615 or 1616), alongside a number of other devices and technical concepts.[8] It was widely believed that in 1617, Vrančić, then aged 65 and seriously ill, implemented his design and tested the parachute by jumping from St Mark's Campanile,[9] from a bridge nearby,[10] or from St Martin's Cathedral in Bratislava.[11][12] In various publications it was falsely claimed that the event was documented some thirty years later by John Wilkins, founder and secretary of the Royal Society in London in his book Mathematical Magick or, the Wonders that may be Performed by Mechanical Geometry, published in London in 1648.[10] However, in this book, John Wilkins wrote about flying, not about parachutes. He neither mentions Faust Vrančić nor a parachute jump nor any event in 1617, and doubts about this test along with no written evidence of its occurrence, lead to the conclusion that it never occurred, and was caused by a misreading of historical notes.[13]

Modern times

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2009) |

18th and 19th centuries

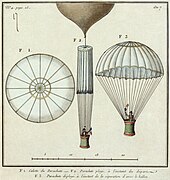

The modern parachute was invented in the late 18th century by Louis-Sébastien Lenormand in France, who made the first recorded public jump in 1783. Lenormand also sketched his device beforehand.

Two years later, in 1785, Lenormand coined the word "parachute" by hybridizing the French prefix paracete, meaning to protect against, and chute, the French word for fall, to describe the aeronautical device's real function.[citation needed]

Also in 1785, Jean-Pierre Blanchard demonstrated it as a means of safely disembarking from a hot-air balloon. While Blanchard's first parachute demonstrations were conducted with a dog as the passenger, he later claimed to have had the opportunity to try it himself in 1793 when his hot air balloon ruptured and he used a parachute to descend (this event was not witnessed by others).

Subsequent development of the parachute focused on it becoming more compact. While the early parachutes were made of linen stretched over a wooden frame, in the late 1790s, Blanchard began making parachutes from folded silk, taking advantage of silk's strength and light weight. In 1797, André Garnerin made the first descent using such a parachute. Garnerin also invented the vented parachute, which improved the stability of the fall.

Eve of World War I

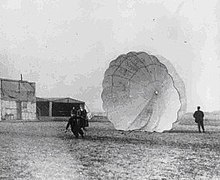

In 1907 Charles Broadwick demonstrated two key advances in the parachute he used to jump from hot air balloons at fairs. He folded his parachute into a pack he wore on his back. And the parachute was pulled from the pack by a static line attached to the balloon. When Broadwick jumped from the balloon, the static line became taut, pulled the parachute from the pack, and then snapped.[15]

In 1911 a successful test took place with a dummy at the Eiffel tower in Paris. The puppet's weight was 75 kg; the parachute's weight was 21 kg. The cables between puppet and the parachute were 9 m long.[14] On February 4, 1912, Franz Reichelt jumped to his death from the tower during initial testing of his wearable parachute.

Also in 1911, Grant Morton made the first parachute jump from an airplane, a Wright Model B piloted by Phil Parmalee, at Venice Beach, California. Morton's device was of the "throw-out" type where he held the parachute in his arms as he left the aircraft. In the same year, a Russian inventor Gleb Kotelnikov invented the first knapsack parachute,[16] although Hermann Lattemann and his wife Käthe Paulus had been jumping with bagged parachutes in the last decade of the 19th century.

In 1912, on a road near Tsarskoye Selo, years before it became part of St. Petersburg, Kotelnikov successfully demonstrated the braking effects of a parachute by accelerating a Russo-Balt automobile to its top speed and then opening a parachute attached to the back seat, thus also inventing the drogue parachute.[16]

On March 1, 1912, U.S. Army Captain Albert Berry made the first (attached-type) parachute jump in the United States from a fixed-wing aircraft, a Benoist pusher, while flying above Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, Missouri. The jump utilized a "pack" style parachute stored or housed in a casing on the jumper's body.

Štefan Banič from Slovakia built the first parachutes to see use beyond the experimental stage, patenting his design in 1914.[17] He tested his umbrella-like device by jumping from an airplane with it, and sold (or donated) the patent to the United States military, receiving very little money or fame for it.[18] On June 21, 1913, Georgia Broadwick became the first woman to parachute-jump from a moving aircraft, doing so over Los Angeles, California.[19] In 1914, while doing demonstrations for the U.S. Army, Broadwick deployed her chute manually, thus becoming the first person to jump free-fall.

The first military use of the parachute was by artillery observers on tethered observation balloons in World War I. These were tempting targets for enemy fighter aircraft, though difficult to destroy, due to their heavy anti-aircraft defenses. Because it was difficult to escape from them, and dangerous when on fire due to their hydrogen inflation, observers would abandon them and descend by parachute as soon as enemy aircraft were seen. The ground crew would then attempt to retrieve and deflate the balloon as quickly as possible. The main part of the parachute was in a bag suspended from the balloon with the pilot wearing only a simple waist harness attached to the main parachute. When the balloon crew jumped the main part of the parachute was pulled from the bag by the crew's waist harness, first the shroud lines, followed by the main canopy. This type of parachute was first adopted on a large scale for their observation balloon crews by the Germans, and then later by the British and French. While this type of unit worked well from balloons, it had mixed results when used on fixed-wing aircraft by the Germans, where the bag was stored in a compartment directly behind the pilot. In many instances where it did not work the shroud lines became entangled with the spinning aircraft. Although a number of famous German fighter pilots were saved by this type of parachute, including Hermann Göring,[20] no parachutes were issued to Allied "heavier-than-air" aircrew, since it was thought at the time that if a pilot had a parachute he would jump from the plane when hit rather than trying to save the aircraft.[21]

Airplane cockpits at that time also were not large enough to accommodate a pilot and a parachute, since a seat that would fit a pilot wearing a parachute would be too large for a pilot not wearing one. This is why the German type was stowed in the fuselage, rather than being of the "backpack" type. Weight was – at the very beginning – also a consideration, since planes had limited load capacity. Carrying a parachute impeded performance and reduced the useful offensive and fuel load.

In the U.K., Everard Calthrop, a railway engineer and breeder of Arab horses, invented and marketed through his Aerial Patents Company a "British Parachute" and the "Guardian Angel" parachute. Thomas Orde-Lees, known as the "Mad Major," demonstrated that parachutes could be used successfully from a low height (he jumped from Tower Bridge in London) which led to parachutes being used by the balloonists of the Royal Flying Corps, though they were not available for aircraft.

In 1911, Solomon Lee Van Meter, Jr. of Lexington Kentucky, submitted for and in July 1916 received a patent for a backpack style parachute – the Aviatory Life Buoy.[22] His self-contained device featured a revolutionary quick-release mechanism – the ripcord – that allowed a falling aviator to expand the canopy only when safely away from the disabled aircraft.[23]

In 1918 the German air service introduced a parachute designed by Unteroffizier Otto Heinecke, an airship ground crewman, and thus became the world's first, and at the time only, air service to introduce a standard parachute. Despite Germany equipping their pilots with parachutes, their efficacy was relatively poor. As a result, many pilots died while using them, including aces such as Oberleutnant Erich Löwenhardt (who fell from 3,600 metres (11,800 ft) after being accidentally rammed by another German aircraft) and Fritz Rumey who tested it in 1918, only to have it fail at a little over 900 m (3,000 ft). Out of the first 70 German airmen to bail out, around a third died.[24] These fatalities were mostly due to the chute or ripcord becoming entangled in the airframe of their spinning aircraft or because of harness failure, a problem fixed in later versions of the Heinecke parachute.[24] High as the failure rate was, carrying a Heinecke parachute certainly beat the alternative and the general effectiveness of the Heinecke parachute can be gauged by the fact that the French, British, American and Italian air services later based their first parachute designs on the Heinecke parachute to varying extents.[25]

In the UK Sir Frank Mears who was serving as a Major in the Royal Flying Corps in France (Kite Balloon section) registered a patent in July 1918 for a parachute with a quick release buckle, known as the "Mears parachute" which was in common use from then onwards.[26]

Post-World War I

The experience with parachutes during the war highlighted the need to develop a design that could be reliably used to exit a disabled airplane. For instance, tethered parachutes did not work well when the aircraft was spinning. After the war, Major Edward L. Hoffman of the United States Army led an effort to develop an improved parachute by bringing together the best elements of multiple parachute designs. Participants in the effort included Leslie Irvin and James Floyd Smith. The team eventually created the Airplane Parachute Type-A. This incorporated three key elements,

- storing the parachute in a soft pack worn on the back, as demonstrated by Charles Broadwick in 1906;

- a ripcord for manually deploying the parachute at a safe distance from the airplane, from a design by Albert Leo Stevens; and

- a pilot chute that draws the main canopy from the pack.

In 1919, Irvin successfully tested the parachute by jumping from an airplane. The Type-A parachute was put into production and over time saved a number of lives.[15] The effort was recognized by the awarding of the Robert J. Collier Trophy to Major Edward L. Hoffman in 1926.[27]

Irvin became the first person to make a premeditated free-fall parachute jump from an airplane. An early brochure of the Irvin Air Chute Company credits William O'Connor as having become, on August 24, 1920 at McCook Field near Dayton, Ohio, the first person to be saved by an Irvin parachute.[28] Another life-saving jump was made at McCook Field by test pilot Lt. Harold H. Harris on October 20, 1922. Shortly after Harris' jump, two Dayton newspaper reporters suggested the creation of the Caterpillar Club for successful parachute jumps from disabled aircraft.

In 1924 Gleb Kotelnikov of Russia became the first parachutist to apply the soft packing of a parachute instead of a hard casing.[29]

Beginning with Italy in 1927, several countries experimented with using parachutes to drop soldiers behind enemy lines. The regular Soviet Airborne Troops were established as early as 1931 after a number of experimental military mass jumps starting from August 2, 1930.[16] Earlier the same year, the first Soviet mass jumps led to the development of the parachuting sport in the Soviet Union.[16] By the time of World War II, large airborne forces were trained and used in surprise attacks, as in the battles for Fort Eben-Emael and The Hague, the first large-scale, opposed landings of paratroopers in military history, by the Germans.[30] This was followed later in the war by airborne assaults on a larger scale, such as the Battle of Crete and Operation Market Garden, the latter being the largest airborne military operation ever.[31] Aircraft crew were routinely equipped with parachutes for emergencies as well.[citation needed]

In 1937, drag chutes were used in aviation for the first time, by Soviet airplanes in the Arctic that were providing support for the polar expeditions of the era, such as the first manned drifting ice station North Pole-1. The drag chute allowed airplanes to land safely on smaller ice-floes.[16]

Types

Today's modern parachutes are classified into two categories – ascending and descending canopies. All ascending canopies refer to paragliders, built specifically to ascend and stay aloft as long as possible. Other parachutes, including ram-air non-elliptical, are classified as descending canopies by manufacturers.

Some modern parachutes are classified as semi-rigid wings, which are maneuverable and can make a controlled descent to collapse on impact with the ground.

Round

Round parachutes are purely a drag device (that is, unlike the ram-air types, they provide no lift) and are used in military, emergency and cargo applications. These have large dome-shaped canopies made from a single layer of triangular cloth gores. Some skydivers call them "jellyfish 'chutes" because of the resemblance to the marine organisms. Modern sport parachutists rarely use this type. The first round parachutes were simple, flat circulars. These early parachutes suffered from instability caused by oscillations. A hole in the apex helped to vent some air and reduce the oscillations. Many military applications adopted conical, i.e., cone-shaped, or parabolic (a flat circular canopy with an extended skirt) shapes, such as the United States Army T-10 static-line parachute. A round parachute with no holes in it is more prone to oscillate, and is not considered to be steerable.

Forward speed (5–13 km/h) and steering can be achieved by cuts in various sections (gores) across the back, or by cutting four lines in the back thereby modifying the canopy shape to allow air to escape from the back of the canopy, providing limited forward speed. Other modifications sometimes used are cuts in various sections (gores) to cause some of the skirt to bow out. Turning is accomplished by forming the edges of the modifications, giving the parachute more speed from one side of the modification than the other. This gives the jumpers the ability to steer the parachute (such as the United States Army MC series parachutes), enabling them to avoid obstacles and to turn into the wind to minimize horizontal speed at landing.

Cruciform (square)

The unique design characteristics of cruciform parachutes decreases oscillation (its user swinging back and forth) and violent turns during descent. This technology will be used by the United States Army as it replaces its older T-10 parachutes with T-11 parachutes under a program called Advanced Tactical Parachute System (ATPS). The ATPS canopy is a highly modified version of a cross/ cruciform platform and is square in appearance. The ATPS system will reduce the rate of descent by 30 percent from 21 feet per second (6.4 m/s) to 15.75 feet per second (4.80 m/s). The T-11 is designed to have an average rate of descent 14% slower than the T-10D, thus resulting in lower landing injury rates for jumpers. The decline in rate of descent will reduce the impact energy by almost 25% to lessen the potential for injury.

Annular and pull down apex

A variation on the round parachute is the pull down apex parachute. Invented by a Frenchman named Pierre-Marcel Lemoigne,[32][33][34] it is called a Para-Commander canopy in some circles, after the first model of the type. It is a round parachute, but with suspension lines to the canopy apex that apply load there and pull the apex closer to the load, distorting the round shape into a somewhat flattened or lenticular shape.

Some designs have the fabric removed from the apex to open a hole through which air can exit, giving the canopy an annular geometry. They also have decreased horizontal drag due to their flatter shape and, when combined with rear-facing vents, can have considerable forward speed.

Rogallo wing

Sport parachuting has experimented with the Rogallo wing, among other shapes and forms. These were usually an attempt to increase the forward speed and reduce the landing speed offered by the other options at the time. The ram-air parachute's development and the subsequent introduction of the sail slider to slow deployment reduced the level of experimentation in the sport parachuting community. The parachutes are also hard to build.

Ribbon and Ring

Ribbon and ring parachutes have similarities to annular designs. They are frequently designed to deploy at supersonic speeds. A conventional parachute would instantly burst upon opening and be shredded at such speeds. Ribbon parachutes have a ring-shaped canopy, often with a large hole in the centre to release the pressure. Sometimes the ring is broken into ribbons connected by ropes to leak air even more. These large leaks lower the stress on the parachute so it does not burst or shred when it opens. Ribbon parachutes made of Kevlar are used on nuclear bombs, such as the B61 and B83.[35]

Ram-air

Most modern parachutes are self-inflating "ram-air" airfoils known as a parafoil that provide control of speed and direction similar to paragliders. Paragliders have much greater lift and range, but parachutes are designed to handle, spread and mitigate the stresses of deployment at terminal velocity. All ram-air parafoils have two layers of fabric—top and bottom—connected by airfoil-shaped fabric ribs to form "cells". The cells fill with high pressure air from vents that face forward on the leading edge of the airfoil. The fabric is shaped and the parachute lines trimmed under load such that the ballooning fabric inflates into an airfoil shape. This airfoil is sometimes maintained by use of fabric one-way valves called airlocks. The first ram-air test jump was performed by United States Navy test jumper Joe Crotwell.

Varieties

Personal ram-air parachutes are loosely divided into two varieties – rectangular or tapered – commonly called "squares" or "ellipticals", respectively. Medium-performance canopies (reserve-, BASE-, canopy formation-, and accuracy-type) are usually rectangular. High-performance, ram-air parachutes have a slightly tapered shape to their leading and/or trailing edges when viewed in plan form, and are known as ellipticals. Sometimes all the taper is in the leading edge (front), and sometimes in the trailing edge (tail).

Ellipticals are usually used only by sport parachutists. They often have smaller, more numerous fabric cells and are shallower in profile. Their canopies can be anywhere from slightly elliptical to highly elliptical, indicating the amount of taper in the canopy design, which is often an indicator of the responsiveness of the canopy to control input for a given wing loading, and of the level of experience required to pilot the canopy safely.

The rectangular parachute designs tend to look like square, inflatable air mattresses with open front ends. They are generally safer to operate, because they are less prone to dive rapidly with relatively small control inputs, they are usually flown with lower wing loadings per square foot of area, and they glide more slowly. They typically have a lower glide ratio.

Wing loading of parachutes is measured similarly to that of aircraft, comparing exit weight to area of parachute fabric. Typical wing loading for students, accuracy competitors, and BASE jumpers is less than 5 kg per square meter – often 0.3 kilograms per square meter or less. Most student skydivers fly with wing loading below 5 kg per square meter. Most sport jumpers fly with wing loading between 5 and 7 kg per square meter, but many interested in performance landings exceed this wing loading. Professional Canopy pilots compete with wing loading of 10 to over 15 kilograms per square meter. While ram-air parachutes with wing loading higher than 20 kilograms per square meter have been landed, this is strictly the realm of professional test jumpers.

Smaller parachutes tend to fly faster for the same load, and ellipticals respond faster to control input. Therefore, small, elliptical designs are often chosen by experienced canopy pilots for the thrilling flying they provide. Flying a fast elliptical requires much more skill and experience. Fast ellipticals are also considerably more dangerous to land. With high-performance elliptical canopies, nuisance malfunctions can be much more serious than with a square design, and may quickly escalate into emergencies. Flying highly loaded, elliptical canopies is a major contributing factor in many skydiving accidents, although advanced training programs are helping to reduce this danger.

High-speed, cross-braced parachutes, such as the Velocity, VX, XAOS and Sensei, have given birth to a new branch of sport parachuting called "swooping." A race course is set up in the landing area for expert pilots to measure the distance they are able to fly past the 1.5-metre (4.9 ft) tall entry gate. Current world records exceed 180 metres (590 ft).

Aspect ratio is another way to measure ram-air parachutes. Aspect ratios of parachutes are measured the same way as aircraft wings, by comparing span with chord. Low aspect ratio parachutes, i.e., span 1.8 times the chord, are now limited to precision landing competitions. Popular precision landing parachutes include Jalbert (now NAA) Para-Foils and John Eiff's series of Challenger Classics. While low aspect ratio parachutes tend to be extremely stable, with gentle stall characteristics, they suffer from steep glide ratios and a small tolerance, or "sweet spot", for timing the landing flare.

Because of their predictable opening characteristics, parachutes with a medium aspect ratio around 2.1 are widely used for reserves, BASE, and canopy formation competition. Most medium aspect ratio parachutes have seven cells.

High aspect ratio parachutes have the flattest glide and the largest tolerance for timing the landing flare, but the least predictable openings. An aspect ratio of 2.7 is about the upper limit for parachutes. High aspect ratio canopies typically have nine or more cells. All reserve ram-air parachutes are of the square variety, because of the greater reliability, and the less-demanding handling characteristics.

General characteristics

Main parachutes used by skydivers today are designed to open softly. Overly rapid deployment was an early problem with ram-air designs. The primary innovation that slows the deployment of a ram-air canopy is the slider; a small rectangular piece of fabric with a grommet near each corner. Four collections of lines go through the grommets to the risers (risers are strips of webbing joining the harness and the rigging lines of a parachute). During deployment, the slider slides down from the canopy to just above the risers. The slider is slowed by air resistance as it descends and reduces the rate at which the lines can spread. This reduces the speed at which the canopy can open and inflate.

At the same time, the overall design of a parachute still has a significant influence on the deployment speed. Modern sport parachutes' deployment speeds vary considerably. Most modern parachutes open comfortably, but individual skydivers may prefer harsher deployment.

The deployment process is inherently chaotic. Rapid deployments can still occur even with well-behaved canopies. On rare occasions deployment can even be so rapid that the jumper suffers bruising, injury, or death. Reducing the amount of fabric decreases the air resistance. This can be done by making the slider smaller, inserting a mesh panel, or cutting a hole in the slider.

Deployment

Reserve parachutes usually have a ripcord deployment system, which was first designed by Theodore Moscicki, but most modern main parachutes used by sports parachutists use a form of hand-deployed pilot chute. A ripcord system pulls a closing pin (sometimes multiple pins), which releases a spring-loaded pilot chute, and opens the container; the pilot chute is then propelled into the air stream by its spring, then uses the force generated by passing air to extract a deployment bag containing the parachute canopy, to which it is attached via a bridle. A hand-deployed pilot chute, once thrown into the air stream, pulls a closing pin on the pilot chute bridle to open the container, then the same force extracts the deployment bag. There are variations on hand-deployed pilot chutes, but the system described is the more common throw-out system.

Only the hand-deployed pilot chute may be collapsed automatically after deployment—by a kill line reducing the in-flight drag of the pilot chute on the main canopy. Reserves, on the other hand, do not retain their pilot chutes after deployment. The reserve deployment bag and pilot chute are not connected to the canopy in a reserve system. This is known as a free-bag configuration, and the components are often lost during a reserve deployment.

Occasionally, a pilot chute does not generate enough force either to pull the pin or to extract the bag. Causes may be that the pilot chute is caught in the turbulent wake of the jumper (the "burble"), the closing loop holding the pin is too tight, or the pilot chute is generating insufficient force. This effect is known as "pilot chute hesitation," and, if it does not clear, it can lead to a total malfunction, requiring reserve deployment.

Paratroopers' main parachutes are usually deployed by static lines that release the parachute, yet retain the deployment bag that contains the parachute—without relying on a pilot chute for deployment. In this configuration the deployment bag is known as a direct-bag system, in which the deployment is rapid, consistent, and reliable.

Safety

A parachute is carefully folded, or "packed" to ensure that it will open reliably. If a parachute is not packed properly it can result in a malfunction where the main parachute fails to deploy correctly or fully. In the United States and many developed countries, emergency and reserve parachutes are packed by "riggers" who must be trained and certified according to legal standards. Sport skydivers are always trained to pack their own primary "main" parachutes.

Exact numbers are difficult to estimate, but approximately one in a thousand sport main parachute openings malfunction, requiring the use of the reserve parachute, although some skydivers have many thousands of jumps and never needed to use their reserve parachute. Reserve parachutes are packed and deployed somewhat differently. They are also designed more conservatively, and are built and tested to more exacting standards, making them more reliable than main parachutes. However, the primary safety advantage of a reserve chute comes from the probability of an unlikely main malfunction being multiplied by the even less likely probability of a reserve malfunction. This yields an even smaller probability of a double malfunction, although the possibility of a main malfunction that cannot be cut away causing a reserve malfunction is a very real risk. In the United States, the average fatality rate is considered to be about 1 in 175,851 jumps.[36] Numerous injuries and fatalities in sport skydiving occur under a fully functional main parachute because the skydiver made an error in judgment while flying the canopy, resulting in high-speed impact with the ground or with a hazard on the ground that might otherwise have been avoided, or collision with another skydiver under canopy.[citation needed]

Malfunctions

Below are listed the malfunctions specific to round parachutes. For malfunctions specific to square parachutes, see Malfunction (parachuting).

- A "Mae West" or "blown periphery" is a type of round parachute malfunction that contorts the shape of the canopy into the outward appearance of a brassiere, presumably one suitable for a buxom woman having the proportions of the late actress Mae West. The column of nylon fabric, buffeted by the wind, rapidly heats from friction and opposite sides of the canopy fuse together in a narrow region, removing any chance of the canopy opening fully.

- An "inversion" occurs when one skirt of the canopy blows between the suspension lines on the opposite side of the parachute and then catches air. That portion then forms a secondary lobe with the canopy inverted. The secondary lobe grows until the canopy turns completely inside out.

- A "barber's pole" describes having a tangle of lines "behind your head and you have to cut away your main chute and pull your reserve."[37]

- The "horseshoe" is an out-of-sequence deployment, when the parachute lines and bag are released before the bag drogue and bridle. This can cause the lines to become tangled or a situation where the parachute drogue is not released from the container.[37]

- "Jumper-In-Tow" involves a static line that does not disconnect and "you are being dragged along in the wild blue yonder."[37]

- The "Streamer" is "dreaded" when the main chute is whistling in the wind, the chutist cuts away, and attempts to open the reserve if there is time.[37]

Records

On August 16, 1960, Joseph Kittinger, in the Excelsior III test jump, set the previous world record for the highest parachute jump. He jumped from a balloon at an altitude of 102,800 feet (31,333 m) (which was also a manned balloon altitude record at the time). A small stabilizer chute deployed successfully, and Kittinger fell for 4 minutes and 36 seconds,[38] also setting a still-standing world record for the longest parachute free-fall, if falling with a stabilizer chute is counted as free-fall. At an altitude of 17,500 feet (5,300 m), Kittinger opened his main chute and landed safely in the New Mexico desert. The whole descent took 13 minutes and 45 seconds.[39] During the descent, Kittinger experienced temperatures as low as −94 °F (−70 °C). In the free-fall stage, he reached a top speed of 614 mph (988 km/h or 274 m/s).[40]

Felix Baumgartner broke Joseph Kittinger's record on October 14, 2012, with a jump from an altitude of 127,852 feet (38,969.3 m) and reaching speeds up to 833.9 mph (1,342.0 km/h or 372.8 m/s).

Alan Eustace made a jump from the stratosphere on October 24, 2014 from an altitude of 135,889.108 feet (41,419 m). However, because Eustace's jump involved a drogue parachute while Baumgartner's did not, their vertical speed and free fall distance records remain in different record categories.

According to Guinness World Records, Yevgeni Nikolayevich Andreyev (Soviet Union) held the official FAI record for the longest free-fall parachute jump (without drogue chute) after falling for 24,500 m (80,380 ft) from an altitude of 25,457 m (83,523 ft) near the city of Saratov, Russia on November 1, 1962, until broken by Felix Baumgartner in 2012.

See also

References

- ^ Ballistic recovery systems A U.S. patent 4607814 A, Boris Popov, August 26, 1986

- ^ Klesius, Michael (January 2011). "How Things Work: Whole-Airplane Parachute". Air & Space. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ a b White 1968, p. 466

- ^ a b White 1968, pp. 462f.

- ^ a b c d White 1968, p. 465

- ^ White 1968, pp. 465f.

- ^ BBC: Da Vinci's Parachute Flies (2000); FoxNews: Swiss Man Safely Uses Leonardo da Vinci Parachute (2008)

- ^ Francis Trevelyan Miller, The world in the air: the story of flying in pictures, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1930, pages 101-106

- ^ He's in the paratroops now, Alfred Day Rathbone, R.M. McBride & Company, 1943, University of California.

- ^ a b Bogdanski, René. The Croation Language by Example. As an example for Diachronic analysis: One of his most important inventions, is without doubt, the parachute, which he experimented and tested on himself, by jumping off a bridge in Venice. As documented by the English bishop John Wilkins (1614–1672) 30 years later, in his book Mathematical Magic... published in London in 1648.

- ^ Parachute on askdefine.com

- ^ Parachute on 321chutelibre (in French)

- ^ Parachuting (on Aero.com): "Like his countryman's concept, Veranzio's seems to have remained an idea only. Though his idea was greatly publicized, no evidence has been found that there ever was a homo volans of his of any other time who tested and proved Veranzio's plan."

- ^ a b De Prins der Geillustreerde Bladen, February 18, 1911, p. 88-89.

- ^ a b Ritter, Lisa (April–May 2010). "Pack Man: Charles Broadwick Invented a New Way of Falling". Air & Space. 25hioj, johhhl, : 68–72. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c d e Parachuting at the site Divo: The Russian Book of records and achievements Template:Ru icon

- ^ U.S. patent 1,108,484

- ^ Štefan Banič, Konštruktér, vynálezca, Matematický ústav, Slovenská akadémia vied, obituary. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ^ Ritter, Lisa (April–May 2010). "Pack Man". Air & Space. 25 (1): 68–72.

- ^ May 1931, Popular Mechanics photo of observation balloon gondola with external bag parachutes used by British Royal Navy

- ^ Lee, Arthur Gould (1968). No parachute. London: Jarrolds. ISBN 0-09-086590-1. (?); Harper & Row 1970, ISBN 978-0060125486

- ^ Aviatory Life Buoy, U.S. patent 1,192,479, July 25, 1916, awarded to inventor Solomon Lee Van Meter, Jr.

- ^ Kentucky Aviation Pioneers – Solomon Lee Van Meter, Jr. (1888–1937), KET Aviation Museum Of Kentucky

- ^ a b Guttman, Jon (May 2012). "Heinecke Parachute: A Leap of Faith for WWI German Airmen". Military History Magazine: p.23.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Mahncke, J O E O (December 2000). "Early Parachutes, An evaluation of the use of parachutes, with special emphasis on the Royal Flying Corps and the German Lufstreitkräfte, until 1918". South African Military History Journal. 11 (6).

- ^ http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/SearchUI/Details?uri=C2987551

- ^ Collier 1920–1929 Recipients, National Aeronautic Association web site.

- ^ Cooper, Ralph S. "The Irvin Parachute, 1924". Earthlink.net. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ Russian parachute of Kotelnikov Template:Ru icon

- ^ Dr L. de Jong, 'Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog', (Dutch language) part 3, RIOD, Amsterdam, 1969

- ^ Dr L. de Jong, 'Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog', (Dutch language) part 10a-II, RIOD, Amsterdam, 1980

- ^ Pierre Marcel Lemoigne, U.S. patent 3,228,636 (filed: November 7, 1963; issued: January 11, 1966).

- ^ Palau, Jean-Michel (February 20, 2008). "Historique du Parachutisme Ascensionnel Nautique" (in French). Le Parachutisme Ascensionnel Nautique. Retrieved October 22, 2013. Includes photo of Lemoigne.

- ^ See also: Theodor W. Knacke, "Technical-historical development of parachutes and their applications since World War I (Technical paper A87-13776 03-03)," 9th Aerodynamic Decelerator and Balloon Technology Conference (Albuquerque, New Mexico; October 7–9, 1986) (New York, N.Y.: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 1986), pages 1-10.

- ^ Mitcheltree, R; Witkowski, A. "High Altitude Test Program for a Mars Subsonic Parachute" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and AstronauticsTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Skydiving Safety". United States Parachute Association. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Scott Royce E. "Bo." Jump School at Fort Benning (originally published in a column called DUSTOFF in the July - August 1988 Issue of the Screaming Eagle Magazine)

- ^ Jeffrey S. Hampton (December 15, 2003). "'Hero of Aviation' speaks about record-setting free fall". The Virginian-Pilot. p. Y1.

- ^ Tim Friend (August 18, 1998). "Out of thin air His free fall from 20 miles (32 km) put NASA on firm footing". USA Today. p. 1D.

- ^ "Data of the stratospheric balloon launched on 8/16/1960 For EXCELSIOR III". Stratocat.com.ar. September 25, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

Sources

- White, Lynn (1968). "The Invention of the Parachute". Technology and Culture. 9 (3): 462–467. doi:10.2307/3101655. JSTOR 3101655Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

External links

- CSPA The Canadian Sport Parachuting Association—The governing body for sport skydiving in Canada

- First jump with parachute from moving plane - Scientific American, June 7, 1913

- Parachute History

- Program Executive Office (PEO) Soldier

- Skydiving education

- The 2nd FAI World Championships in Canopy Piloting - 2008 at Pretoria Skydiving Club South Africa

- USPA The United States Parachute Association—The governing body for sport skydiving in the U.S.

- The Parachute History Collection at Linda Hall Library (text-searchable PDFs)

- "How Armies Hit The Silk" June 1945, Popular Science James L. H. Peck - detailed article on parachutes