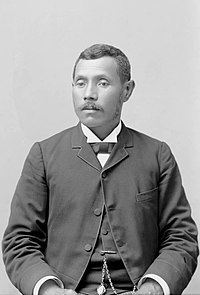

William Pūnohu White

William Pūnohu White | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Kingdom of Hawaii House of Representatives for the district of Lahaina, Maui | |

| In office 1890–1893 | |

| Member of the Territory of Hawaii Senate for the Second District | |

| In office February 20, 1901 – July 29, 1901 | |

| Sheriff of Maui County | |

| In office January 4, 1904 – January 16, 1904 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 6, 1851 Lahaina, Maui, Kingdom of Hawaii |

| Died | November 2, 1925 (aged 74) Honolulu, Oʻahu, Territory of Hawaii |

| Nationality | Kingdom of Hawaii United States |

| Political party | Home Rule National Liberal National Reform |

| Spouse | Ester Apuna Akina |

| Children | Ellen White Kahaulelio and Samuel Tensung Leialoha White |

| Parent(s) | John White, Jr. |

| Occupation | Lawyer, Politician, Newspaper Editor |

| Nickname | "Bila Aila" or "Bila Aila" (Oily Bill) |

William Pūnohuʻāweoweoʻulaokalani White (August 6, 1851 – November 2, 1925) was a Hawaiian lawyer, politician, and newspaper editor. He became a political statesman and orator during the final years of the Kingdom of Hawaii and the beginnings of the Territory of Hawaii. Despite being a leading Native Hawaiian politician in this era, his legacy has been largely forgotten or portrayed in a negative light, largely because of a reliance on pro-annexationist English-language sources to write Hawaiian history. He was known by the nickname of "Pila Aila" or "Bila Aila" (translated as Oily Bill) for his oratory skills.[1][2]

Born in Lahaina, Maui, of mixed Native Hawaiian and English descent, White inherited the oratory skills of his Hawaiian ancestor Kaiakea, a legendary orator for King Kamehameha I. Serving as a legislator in the legislative assemblies of 1890 and 1892, he became a political leader for the Liberal faction in the government and established himself as a leader in the opposition to the unpopular Bayonet Constitution of 1887. Throughout both legislatures, White led attempts to pass bills calling for a constitutional convention. He was criticized by the missionary Reform party for his support of the controversial lottery and opium bills. Alongside Joseph Nāwahī, he was a principal author of the proposed 1893 Constitution with Queen Liliʻuokalani. They were decorated Knight Commanders of the Royal Order of Kalākaua for their service and contribution to the monarchy. When an attempt by the queen to promulgate this constitution failed on January 14, 1893, White's opponents tried to slander him in the English-language press and to diminish his support among Native Hawaiians by claiming he had tried to incite the people to storm the palace and harm the queen and her ministers. White denied these charges and threatened to sue the newspapers. Three days after the attempted promulgation, the queen was deposed in a coup during the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893.

During the Provisional Government of Hawaii and the Republic of Hawaii that followed it, he remained loyal to the monarchy. Returning to Lahaina, he helped organize native resistance on his home island of Maui and was arrested for running out a pro-annexationist pastor at Waineʻe Church. He was elected in 1896 as honorary president of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina (Hawaiian Patriotic League), a patriotic organization established after the overthrow to oppose annexation. In 1897 he became an editor of the short-lived anti-annexationist newspaper Ke Ahailono o Hawaii (translated as The Hawaiian Herald) run by members of Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association). After the annexation of Hawaii to the United States, he was elected as a senator of the first Hawaiian Territorial legislature of 1901 for the Home Rule Party.

Early life

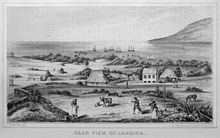

White was born on August 6, 1851,[1][3][4] at Lahaina, on the island of Maui, to John White, Jr,[5] the son of John White, Sr. and Keawe. He was of Native Hawaiian and English descent, thus known as a hapa-haole in Hawaiian and as a "half-caste" in the English press.[1][3][6][7] His grandfather John White, Sr. was regarded as one of the oldest foreign residents in Hawaii at the time of his death. Known as "Jack" White", he was an Englishman originally from Plymouth or Devonshire. During the French Revolutionary Wars, he served on the frigate HMS Amelia, which was part of the North Sea fleet under the command of British Vice Admiral Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Duncan, during his engagement with the Dutch. Sometime in 1796 or 1797, he arrived in Lahaina and later settled as a permanent resident in 1802 during the final years of the conquest and unification of the Kingdom of Hawaii and a foreigner in the court retinue of King Kamehameha I. He received lands on Maui in the Great Mahele in 1848. After residing in the Hawaiian Islands for more than sixty years, he died on August 9, 1857, at the age of either eighty-four or ninety.[8][9] He was living with his son-in-law Maui sugar planter Linton L. Torbert around the time of his death.[8]

From his paternal grandmother Keawe, he was descended from Kaiakea, an aliʻi (high chief) of Molokaʻi, who served as a political counselor, orator and many other different positions during the reign of the first Hawaiian king Kamehameha I.[3] In 1902, the Ka Nupepa Kuokoa printed a brief biography, noting: "...Kaiakea was a wise counsellor in ancient times in his occupation taught by his grandfathers from Kapouhiwaokalani to the sons, Mahinuiakalani and Kauauanuiamahi and Kuikai, on down to Kukalanihoouluae, the own father of Kaiakea. From these comes Kaiakea's political knowledge, that as an architect, an orator, a composer of the historical and genealogical chants, an important genealogical source for these isladns and the one who by himself and with his chiefly children arranged the genealogy of the major chiefs of Hawaii, Maui, and Molokai from the high chiefly ranks to the low chiefly ranks."[10]

White became a lawyer and skilled orator. In the Hawaiian tradition, his skills were attributed to the kuleana (responsibility) of his family as descendants of Kaiakea. As a political leader, he received strong support in the Native Hawaiian community.[3] During his terms in the legislature, he became known by the nickname of "Pila Aila" or "Bila Aila" (Oily Bill) for his ability to speak to and humorously charm large crowds. He embraced this moniker although his opponents used it negatively to denigrate him as a slick, smooth-talking demagogue who had an evil influence on his constituents.[1][2][7][11]

He married Ester Apuna Akina, the sister of fellow statesman Joseph Apukai Akina.[3][6] They had four children including: Ellen White, wife of David K. Kahaulelio, and Samuel Tensung Leialoha White, who became an assistant city engineer for Honolulu.[1][12]

Political career during the monarchy

His first official post of note was as an agent of "acknowledgement to instruments" on September 12, 1884.[13] He became a member of the Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association), a Hawaiian political group founded in 1888 to oppose the Bayonet Constitution and promote Native Hawaiian leadership in the government.[14][15] After the adoption of the unpopular constitution, White had given a speech in Hilo against it.[16]

From 1890 to 1892, he served as a member of the House of Representatives, the lower house of the Hawaiian legislature, for the district of Lahaina on the island of Maui.[13][17] In his first term, he was elected as a member of the National Reform Party. This party had been established in opposition to the Reform Party (consisting of many descendants of American missionaries[18]), which had forced King Kalākaua to sign the unpopular Bayonet Constitution of 1887.[19][20] After the 1890 bi-annual session commenced, Kalakaua died while in San Francisco and was succeeded by his sister Queen Liliʻuokalani.[21]

Legislature of 1892–93

In the election of 1892 White changed party alliance and ran as a candidate for the newly created National Liberal Party, defeating Reform candidate John W. Kalua for the seat of Lahaina in the House of Representatives.[22] The Liberal Party advocated for a constitutional convention to draft a new constitution to replace the unpopular Bayonet Constitution. However, the party was divided between radicals and more conciliatory groups. Joseph Nāwahī (the representative of Hilo) and White soon became the leaders of the factions of the Liberals loyal to the queen against the more radical members including John E. Bush and Robert William Wilcox, who were advocating for drastic changes such increased power for the people and a republican form of government.[23] From May 28, 1892, to January 14, 1893, the legislature of the Kingdom convened for an unprecedented 171 days, which later historian Albertine Loomis dubbed the "Longest Legislature".[24] This session was characterized by a series of resolutions of want of confidence, resulting in the ousting of a number of Queen Liliʻuokalani's appointed cabinet ministers, and debates over the passage of the controversial lottery and opium bills.[25]

During this session, White presented petitions for a new constitution from his constituents and introduced a bill on June 29 to convene a constitutional convention that was referred to a selected committee. He supported the lottery bill and the opium bill, which were intended to alleviate the economic depression on the islands' sugar industry caused by the passage of the McKinley Tariff. The bills were controversial, and divisive issues among the members. He was one of three legislators to introduce an opium licensing bill (July 9) for legislative debate although the final bill adopted was another version written by Clarence W. Ashford. On August 30, he introduced the lottery bill, aimed at creating a national lottery system for raising governmental revenue, which was supported by the queen. According to Liliʻuokalani, White "watched his opportunity and railroaded the last two bills through the house". Both these bills passed the legislature after contentious debates.[26]

Along with his political ally Nāwahī, White was decorated with the honor of Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua, at a ceremony in the Blue Room of ʻIolani Palace, on the morning of January 14, for his work and patriotism during the legislative session.[27][28] The legislative assembly was prorogued on the same day, two hours later, at a noon ceremony officiated by the queen at Aliʻiōlani Hale, which was situated across the street from the palace. The Daily Bulletin newspaper noted: "All of the Hawaiian members of the Legislature were present, and one of them, Rep. White, displayed a star of the Order of Kalakaua".[29]

During the overthrow

A strong proponent for a new constitution, White helped Queen Liliʻuokalani draft the 1893 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Nāwahī was the other principal author, and Samuel Nowlein, captain of the Household Guard, was another contributor. These three had been meeting with the queen in secret since August 1892 after attempts to abrogate the Bayonet Constitution by legislative decision through a constitutional convention had proved largely unsuccessful. The proposed constitution would increase the power of the monarchy, restore voting rights to economically disenfranchised Native Hawaiians and Asians, and remove the property qualification for suffrage imposed by the Bayonet Constitution, among other changes. On the afternoon of January 14, after the knighting ceremony of White and Nāwahī and the prorogation of the legislature, members of Hui Kālaiʻāina and a delegation of native leaders marched to ʻIolani Palace with a sealed package containing the constitution. According to William DeWitt Alexander, this was pre-planned by the queen to take place while she met with her newly appointed cabinet ministers in the Blue Room of the palace. She was attempting to promulgate the constitution during the recess of the legislative assembly. However, these ministers, including Samuel Parker, William H. Cornwell, John F. Colburn, and Arthur P. Peterson, were either opposed to or reluctant to support the new constitution.[30]

Crowds of citizens had gathered outside the steps and gates of ʻIolani Palace expecting the announcement of a new constitution. Among the crowds were White and members of Hui Kālaiʻāina who had presented a sealed package containing the constitution.[31][32] After the ministers' refusal to sign the new constitution, the queen stepped out onto the balcony asking the assembled people to return home, declaring "their wishes for a new constitution could not be granted just then, but will be some future day". Representative White also gave a speech to this crowd on the palace steps although the exact nature of what he said is disputed.[33] Opponents of the monarchy, especially the conservatives in the Reform Party, later claimed he gave an inflammatory and violent speech inciting the crowd to storm the palace and "go in and kill and bury" either the queen or her cabinet ministers. The speech may have been in Hawaiian and was only paraphrased in the English press.[31][34] On January 16, The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, an English newspaper in Honolulu, sympathetic to the Reformer, reported:

Rep. White then proceeded to the steps of the Palace and began an address. He told the crowd that the Queen and the Cabinet had betrayed them, and that instead of going home peaceably they should go into the Palace and kill and bury her. Attempts were made to stop him which he resisted, saying that he would never close his mouth until the new Constitution was granted. Finally he yielded to the expostulations of Col. Boyd and others, threw up his hands and declared that he was pau, for the present. After this the audience assembled dispersed.[31][note 1]

The political fallout of the queen's actions led to citywide political rallies and meetings in Honolulu. Anti-monarchists, annexationists, and leading Reformist politicians including Lorrin A. Thurston formed the Committee of Safety in protest of the "revolutionary" action of the queen and conspired to depose her. In response, royalists formed the Committee of Law and Order and met at the palace square on January 16. White, Nāwahī, Bush, Wilcox, and Antone Rosa and other pro-monarchist leaders gave speeches in support for the queen and the government. However, in their attempts to be cautious and not provoke the opposition, they adopted a resolution stating that "the Government does not and will not seek any modification of the Constitution by any other means than those provided in the organic law".[11][36] In this mass meeting, White also gave a speech denying the violent charges printed in the press against him, claiming that "the other fellows, meaning the Reformers, are crying out before they are hurt" (another paraphrasing published in The Daily Bulletin).[11] Minister Cornwell (one of the individuals the papers claimed he intended to harm) later stated in his testimony in the Blount Report:

A few remarks were made by the Hon. William White, the representative for Lahaina, to the effect that, while the people regretted the Queen's inability to grant the wishes of the people, they accept the assurances of the Queen and await the proper time, which, if they were successful at the next election to be held, would be at the meeting of the Legislature in 1894. The insurgents have falsely reported the remarks of Mr. White, and in their press and otherwise represented him as making an incendiary and threatening speech. The falsehood of such statement, well known to us who were witnesses at the scene, will shortly be proven in the courts of justice, as Mr. White has retained counsel for the purpose of bringing a damage suit for malicious libel[note 2] against the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, the principal organ of the reform party.[37]

Opposing the overthrow and annexation

These actions and the radicalized political climate eventually led to the overthrow of the monarchy, on January 17, 1893, by the Committee of Safety, with the covert support of United States Minister John L. Stevens and the landing of American forces from the USS Boston. After a brief transition under the Provisional Government, the oligarchical Republic of Hawaii was established on July 4, 1894, with Sanford B. Dole as president. During this period, the de facto government, which was composed largely of residents of American and European ancestry, sought to annex the islands to the United States against the wishes of the Native Hawaiians who wanted to remain an independent nation ruled by the monarchy.[38][39]

Resistance on Maui

Residents of Maui began circulating petitions protesting the establishment of the Provisional Government in the districts of Wailuku and Makawao. White was still in Honolulu during the events of the coup d'état, and The Hawaiian Gazette reported rumors that he was one of the candidates for a Hawaiian embassy to Washington, DC, to ask for the restoration of the monarchy under the queen's niece Princess Kaʻiulani.[40] Departing Honolulu on February 7, he returned to Lahaina on the inter-island steamer Waialeale.[41] White remained a royalist and agent to the deposed monarch on Maui and wrote "to the Queen and others about covert issues surrounding her possible re-instatement".[6][34]

In May 1893 he organized the native community of Lahaina in removing the pro-annexationist Reverend Adam Pali of Waineʻe Church, who was asked to vacate the pastor's residence owned by church by July 8. However, these efforts were undone by the central authority in Honolulu and the Maui Presbytery. During their meeting in June, the Hawaiian Evangelical Association (HEA) ruled against the vote of the native congregation. In July the Maui Presbytery reinstated Pali and excommunicated the members of the congregation, including White, who had voted to remove him.[42] The English press in Honolulu cast White in a negative light, claiming he had proved to be a "negative influence over the simple people of the parish".[7] On July 8 a confrontation took place between the leaders of the congregation, who held control of church, and supporters of Rev. Pali, which included Lahaina Circuit Judge Daniel Kahāʻulelio. Using his official position, Judge Kahāʻulelio ordered the arrest of White and the four other leaders of the congregation on charges of "riot and unlawful assembly". They were imprisoned in the local jail to await trial. Represented by John Richardson, the personal attorney of the queen, their trial lasted three days, from August 2 to August 5, 1893. Judge William H. Daniels, of the Wailuku Circuit Court, found no evidence that the defendants had organized or provoked a confrontation and acquitted them of the charges. Consequently, after Rev. Pali's reinstatement, church attendance at Waineʻe plummeted from seventy-five to thirteen members. The excommunicated members continued their resistance and worshipped at the nearby Hale Aloha Church instead.[43]

Waineʻe Church was burned down on June 28, 1894, after sparks from a rubbish fire ignited the wooden belfry of the church. Although the fire was accidental, annexationist Sereno Edwards Bishop, writing in 1897, blamed the Hawaiian royalists and those who had opposed Rev. Pali for the burning of the building. He stated: "The excellent pastor of this church, Reverend A. Pali, had become obnoxious to a majority of his people on account of politics. He had favored the abolition of monarchy, having become, like a majority of his colleagues in the pastorate, exceedingly disgusted with the increasing heathenish tendencies of the court. The dissension arising from Pali's attitude had led to the burning of the fine old stone church by partisans of the Royalist side, and the people were too weak to rebuild." This biased, false report has been repeated in the conventional history of Hawaii written with the use English language sources. The church was later rebuilt and destroyed multiple times and was renamed Waiola Church in 1953.[44][45]

Returning to Honolulu

White became a member of Hui Aloha ʻĀina o Na Kane (Hawaiian Patriotic League for Men), a patriotic group founded shortly after the overthrow of the monarchy to oppose annexation and support the deposed queen. A corresponding female league was also founded as well. The ranks of the men's group were largely composed of the leading native politicians of the former monarchy, including Nāwahī, who served as the president of the group. A delegation (not including White) was elected by its members to represent the case of the monarchy and the Hawaiian people to the United States Commissioner James Henderson Blount sent by President Grover Cleveland to investigate the overthrow.[46] During this politically uncertain time, White traveled to Honolulu at the end of 1893 on the steamer W. G. Hall upon hearing rumors of the monarchy's restoration and returned to Lahaina in January when he discovered the reports were false.[47] The native resistance, the results of the Blount Report, and President Cleveland's refusal to annex the island stopped the annexationist scheme, prompted the Provisional Government to establish an oligarchical government, styling itself the Republic of Hawaii, until a more favorable political climate emerged in Washington.[48] In April 1894 White and John Richardson gave a speech at Lahaina opposing the new regime and asking the people not to participate in the election of delegates to the constitutional convention in Honolulu. Members of Hui Aloha ʻĀina gave speeches and held meetings across much of the island, and it was reported that foreigners and natives alike in Maui (with the exception of Hana) were strongly against the attempts to establish a republic.[49]

At the beginning of January 1895, Robert William Wilcox launched a counter-revolution against the forces of the Republic. Its ultimate failure led to the arrest of many sympathizers of Wilcox and the militant efforts to restore the queen, including Liliʻuokalani and Nāwahī, who were arrested for misprision of treason. Nāwahī died in 1896 from tuberculosis complications contracted during his imprisonment.[50] After Nāwahī's death, White and other Hui Aloha ʻĀina delegates from the different island branches congregated in Honolulu for the election of a new leadership council. On November 28, 1896, in a meeting in which White presided as chairman, James Keauiluna Kaulia was elected as the new president. Two days later, White was chosen as the honorary president of Hui Aloha ʻĀina, over Edward Kamakau Lilikalani, by a majority of the assembled members. The Hawaiian Star reported, "In accepting the position Mr. White thanked the members for the honor and pledged himself to labor for the best interests of the society. He called upon the delegates to inform their constituents of his election and ask them to give him their cordial aid in his work."[51]

In 1897 White became the editor of Ke Ahailono o Hawaii (translated as The Hawaiian Herald), a Hawaiian language newspaper founded by Hui Kālaiʻāina. After the overthrow, this Hawaiian political group switched its political agenda toward opposing annexation to the United States and restoring Liliʻuokalani.[3][14] White co-owned the paper with David Keku and John Kahahawai.[52] The assistant editor was Samuel K. Pua, a colleague of White's in the 1892–93 legislature from Oahu, although Pua would resign in October of the same year.[53] At the conception of Ke Ahailono o Hawaii, the English newspaper The Independent noted that "The New venture under the control of Messrs. White and Pua, should indeed be a White Flower[note 3] of journalism, although the genial 'Sam' could change the euphony by adding another terminal vowel to his name."[55] The paper was published at Honolulu's Makaainana Printing House, owned by F. J. Testa.[55][56] Weekly issues were published from June 4 to October 29, 1897.[52]

Shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898, President William McKinley signed the treaty of annexation for the Republic of Hawaii, but it failed to pass in the United States Senate after the Kūʻē Petitions were submitted by Kaulia and three other Hawaiian delegates as evidence of the strong resistance of the Native Hawaiian community to annexation. Members of Hui Aloha ʻĀina collected over 21,000 signatures opposing an annexation treaty. Another 17,000 signatures were collected by members of Hui Kālaiʻāina but not submitted to Congress because they were asking for the restoration of the queen. After the failure of the treaty, Hawaii was instead annexed by means of a joint resolution called the Newlands Resolution.[14]

Territorial government

After the establishment of the Territory of Hawaii, White became a member of the Home Rule Party, which consisted of former royalists and Native Hawaiians leaders during the monarchy such as Robert William Wilcox, who was elected the first congressional delegate from Hawaii under the Home Rule ticket.[57] In 1901 White was elected to the inaugural Territorial legislature, established after the Hawaiian Organic Act, as a senator from the Second District (corresponding to Maui, Molokaʻi. Lānaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe).[13][58] His brother-in-law, Joseph Apukai Akina, served as Speaker of the House of Representatives.[17]

During this session, the Native Hawaiian legislators' attempted to pass new laws in the interest of the local people including Hawaiian taro farmers and the victims of the 1900 Chinatown fire, among others. However, their agenda was obstructed by the Republicans and the appointed members of territorial government especially Governor Sanford B. Dole, the former president of the Republic. They attempted to decentralized control away from the governor and empower the local government by passing a bill creating the first counties in Hawaii. This county bill, would have created five counties named after former Hawaiian aliʻi, but it was defeated by Dole through a pocket veto before the prorogation of the session.[59] The legislative assembly was later mockingly dubbed the "Lady Dog Legislature" because of extensive legislative debate on the repealing of an 1898 tax on ownership of female dogs. The difficulties of the 1901 legislature would later be used as evidence of the incompetence of Native Hawaiian political leadership.[60][61] Historian Ronald William, Jr., noted:

Hawaiʻi's first territorial legislature has been disparaged in modern published sources with its native leadership characterized as incompetent, ineffective, and shallow. In contrast, the primary-source record of that body reveals a competent, prepared, and engaged native leadership addressing foundational concerns of their constituents through the drafting and support of numerous legislative bills. It conveys a story of legislative leaders hamstrung by a territorial system in which two of the three governmental branches, the judiciary and executive, were appointed. A bitter struggle between these appointed and elected factions resulted in the neutering of much of the agenda of the native-led legislature.[61]

In the next election for the 1903 legislature, White ran again for senator on the Home Rule ticket. Despite expecting an easy victory, he was defeated by Republican candidate Charles H. Dickey due to a split vote caused by the third-party Democrats. White accepted the defeat graciously.[62] A second county bill was passed by the 1903 legislature and approved by Governor Dole, forming Maui County and four other counties on the main Hawaiian Islands.[63][note 4] The first local territorial elections for the county boards of Maui and the other counties were held in November 3.[65] In this election, White ran as the Home Rule candidate for Sheriff of Maui County and defeated the Republican candidate Lincoln M. Baldwin, who had held the previously appointed position of sheriff. The Home Rule Party ended up dominating in the local elections on Maui.[66][note 5] Shortly after his election, White and David H. Kahaulelio, the elected county clerk for Maui, wrote to Dole's successor, Governor George R. Carter, asking him to assemble a conference where the newly elected county officials across the territory could discuss how the county governments should be conducted.[68]

The county act came into effect on January 4.[63][69] However, it was soon placed on file by the Hawaii Supreme Court, awaiting a ruling on its constitutionality. Acting under the instruction of the Governor, High Sheriff Arthur M. Brown ordered the former appointed sheriffs to resume their posts from the elected officials. Brown sent a telegraph, on January 14, to Sheriff Baldwin ordering him to resume his former position and ask White to vacate his office.[70] They expected some amount of difficulty from White and Brown considered sending a force from Honolulu under Deputy High Sheriff Charles F. Chillingsworth to quell any possible insurrection. Baldwin assembled men from his former police force and retook the sheriff's office but White refused to relinquish his position insisting that he wanted "further advice from the Attorney General as to what he should do". The Board of Supervisors met and decided that White should hold office until there was an official notification from Honolulu on the matter. Both Baldwin and Whie agreed to wait. On January 16, 1904, the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled the second county bill as unconstitutional because it ran counter to the Organic Act, effectively voiding the previous local elections. When the official decision was received, White resigned as sheriff.[63][71]

In 1906, he ran for the territorial senate for a third time, as a Home Ruler. His supporters described him as "Safe, sane, and conservative" in their petition letters nominating him for the election. However, the party had been steadily losing powers to the Republican since 1903, and White was defeated by Republican candidate W. J. Coelho by a narrow margin of 1225 to 1281. He ran as a Democrat in the 1908 election for the senate seat from Maui, and was defeated by a margin of 1152 to 1158. After relocating to Honolulu, he ran unsuccessfully in the elections of 1910, 1912, and 1914, as a senator of the fourth and fifth district of Oahu, on the Home Rule ticket. The Home Rule Party formally disbanded in 1912, although a few candidates including White ran in the primary elections of 1914.[72][73]

Death and legacy

From 1901 to 1903, White was the proprietor of the Kalei Nani Sloon in Lahaina, which was advertised in The Maui News.[74] In later life, he moved to Honolulu from Lahaina in 1907. After an illness of eight months, he died on November 2, 1925, at his home at 604 Kalihi near North Queen, in Honolulu.[1] He was buried an unmarked grave at the Kaʻahumanu Society Cemetery, next to where his widow would later be laid to rest.[75]

Despite his popularity in the native community, White was portrayed negatively in the English-language press in his lifetime and in the published histories after his death.[34] As a consequence of his opposition to the powers that overthrew the monarchy and later annexed the islands to the United States, White remains obscure in Hawaiian history.[6] Recent research efforts in Hawaiian academia using Hawaiian language sources have shed more light on White and many other early Native Hawaiian leaders like him.[34][76]

In Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Liliʻuokalani praised the work of Nāwahī and White:

The behavior of these two patriots during the trying scenes of this session, in such marked contrast to that of many others, won them profound respect. They could never be induced to compromise principles, nor did they for one moment falter or hesitate in advocating boldly a new constitution which should accord equal rights to the Hawaiians, as well as protect the interests of the foreigners. The true patriotism and love of country of these men had been recognized by me, and I had decorated them with the order of Knight Commander of Kalakaua.[77]

Honors

Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua.[27]

Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua.[27]

Notes

- ^ William DeWitt Alexander wrote an almost verbatim account in his 1896 book History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy:

"Representative White then proceeded to the front steps of the Palace and began an address. He told the crowd that the Cabinet had betrayed them, and that instead of going home peaceably, they should go into the Palace and kill and bury them. Attempts were made to stop him which he resisted, saying he would never close his mouth until the new Constitution was granted. Finally he yielded to the expostulations of Col. Jas. H. Boyd and others, threw up his hands and said that he was "pau," done for the present. After this the audience dispersed and the Hui Kalaiaina filed out, appearing very much dejected. A few minutes later Messrs. Parker and Cornwell came over to the Government building together, looking as though they had passed through a very severe ordeal. As they entered the building they were complimented by several persons for the stand which they had made."[35]

- ^ No such case has been founded.[34]

- ^ Pua means flower in Hawaiian.[54]

- ^ The main territorial difference between these early counties and the current county system is the division of Hawaii Island (now part of Hawaii County) into West Hawaii County and East Hawaii County. Maui County was made up of the four islands of Maui, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe and Molokaʻi with the exception of the area which formed Kalawao County, the leprosy settlement which remained an independent division without an elected government.[63][64]

- ^ The Home Rulers were able to sweep the county elections for Maui and East Hawaii while the Republicans dominated in the elections of the other counties.[67]

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Former Political Leader Passes". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. November 3, 1925.

- ^ a b Williams 2013, p. 107; Kuykendall 1967, p. 593; "Calm Before Storm". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. May 28, 1892. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Williams, Ronald, Jr. "William Pūnohuaweoweoulaokalani White (1851–1925)". Hawaii Alive. Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 1910 United States Census

- ^ 1866 Census for the Kingdom of Hawaii

- ^ a b c d Williams, Ronald, Jr. "Ola Nā Iwi: Building Future Leaders By Linking Students To The Past" (PDF). Waiola Church. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Smooth William White". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 3, 1894. p. 2.; "Smooth William White". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. February 6, 1894. p. 3.

- ^ a b Cushing 1985, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Torbert, Linton L. (January 31, 1852). "Paper Read By L. L. Torbert, Before the Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society". The Polynesian. Honolulu. p. 1.; "A Veteran Gone To His Rest". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. August 13, 1857. p. 2.; "Decease of an old Resident". The Polynesian. Honolulu. August 15, 1857. p. 2.

- ^ McKinzie 1986, pp. 92–93

- ^ a b c "Popular Meeting – Over Two Thousand Person Assemble on Palace Square – They Pass a Resolution Upholding the Queen and the Government". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. January 17, 1893. p. 2.

- ^ 1890 Census for the Kingdom of Hawaii

- ^ a b c "White, William office record", state archives digital collections, state of Hawaii

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ a b c Silva 2004, pp. 123–163; Silva, Noenoe K. "The 1897 Petitions Protesting Annexation". The Annexation Of Hawaii: A Collection Of Document. University of Hawaii at Manoa. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ Williams 2015, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Earle 1993, p. 75.

- ^ a b Hawaii & Lydecker 1918, pp. 178, 182, 263, 265

- ^ Blount 1895, p. 669.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 448–455

- ^ "The New Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 14, 1890. p. 3.; "Legislative Assembly of 1890". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. May 21, 1890. p. 3.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 474–475

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 514–522, 549; Hawaii & Lydecker 1918, p. 182; Blount 1895, p. 1138; "List Of Candidates". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 3, 1892. p. 4.; "Legislature Of 1892". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 26, 1892. p. 1.

- ^ Williams 2015, p. 24; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 514–522, 547, 554–555; Andrade 1996, pp. 99, 108

- ^ Loomis 1963, pp. 7–27

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 543–545, 549–559.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 543–545, 548, 550; Loomis 1963, pp. 17–18, 23; Blount 1895, p. 862; Twigg-Smith 1998, p. 58

- ^ a b Liliuokalani 1898, p. 300; Kuykendall 1967, p. 581; Williams 2013, p. 80; Williams 2015, p. 25

- ^ "Local And General". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 16, 1893. p. 3.; "Local And General News". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. January 16, 1893. p. 3.; "Local And General News". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. January 17, 1893. p. 9.

- ^ Williams 2013, p. 80; Alexander 1896, pp. 30–31; "The Legislature". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. January 14, 1893. p. 3.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 582–586; Allen 1982, pp. 281–282; Twigg-Smith 1998, pp. 64–67; Williams 2015, pp. 25; Alexander 1896, pp. 29–36

- ^ a b c "Revolution!". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 16, 1893. p. 4.; "Revolution!". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. January 17, 1893. p. 9.; "New Constitution – Presented by the Hui Kalaiaina To-day – Movements of Cabinet Ministers and Foreign Representatives". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. January 14, 1893. p. 3.; "A Revolution In Hawaii". The New York Times. New York. January 29, 1893. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 13, 2001.

- ^ Alexander 1896, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 585–586; Blount 1895, pp. 494, 838, 961; Allen 1982, pp. 290; Williams 2008, p. 114

- ^ a b c d e Williams 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Alexander 1896, p. 35.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 586–594; Menton & Tamura 1999, pp. 21–23; Alexander 1896, pp. 37–51

- ^ Blount 1895, pp. 494, 838, 961

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 586–605, 649; Loomis 1963, pp. 25–26

- ^ Silva 2004, pp. 129–163.

- ^ "Maui News – Politics". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. January 31, 1893. p. 9.

- ^ "Departures". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 8, 1893. p. 3.; "Departures". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. February 14, 1893. p. 12.

- ^ Williams 2008, pp. 27, 47, 69–71, 141.

- ^ Williams 2008, pp. 122–165.

- ^ Williams 2008, pp. 38–73.

- ^ "Waiola Church History, Lahaina Maui". Waiola Church. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ Blount 1895, pp. 1294–1298; "Patriotic Leaguers – They Determine On Secret Actions – A Demand for the Restoration of the Monarchy Favored". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. May 2, 1893. p. 5.

- ^ "Local And General". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. December 20, 1893. p. 3.; "Local Brevities". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 4, 1894. p. 7.; "Local And General News". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. January 3, 1894. p. 3.; "Local Brevities". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. January 5, 1894. p. 5.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 605–606, 623–631.

- ^ "Maui Politics". Hawaii Holomua Progress. Honolulu. April 9, 1894. p. 3.

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 300–304.

- ^ "Local Brevities". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. November 27, 1896. p. 9.; "The Endorsement". The Independent. Honolulu. December 3, 1896. p. 2.; "Hui Aloha Aina – Meet in Arion Hall to Choose a President". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. November 30, 1896. p. 8.; "The Hui Aloha Aina – 'Oily' Bill White Of Lahaina Is Honored By Election". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. November 30, 1896. p. 1.; "Ahahui Aloha Aina". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. December 1, 1896. p. 1.

- ^ a b Chapin 2000, p. 5.

- ^ "Local And General News". The Independent. Honolulu. July 17, 1897. p. 3.; "Local And General News". The Independent. Honolulu. October 28, 1897. p. 3.

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui; Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of pua". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ a b "Ke Ahailono o Hawaii". The Independent. Honolulu. June 3, 1897. p. 2.; "Local And General News". The Independent. Honolulu. June 7, 1897. p. 3.; "Local Brevities". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. June 8, 1897. p. 7.; "Local And General News". The Independent. Honolulu. January 15, 1898. p. 3.

- ^ Hawaii. Supreme Court (1900). F. J. Testa v. J. P. Kahahawai, W. White, D. L. Keku, D. K. Kalauokalani and D. Kalauokalani. Honolulu: Hawaiian Gazette Company Print. pp. 254–258.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Williams 2015, pp. 13–16.

- ^ George & Bachman 1934, p. 11; Andrade 1996, p. 202; Williams 2015, pp. 23–25

- ^ Williams 2015, pp. 25–39.

- ^ Andrade 1996, p. 209.

- ^ a b Williams 2015, pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Maui Republicans Swept All Before Them With Exception of Lanai". Evening Bulletin. Honolulu. November 7, 1902. p. 1.; "Bill White To Pogue". Evening Bulletin. Honolulu. November 18, 1902. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Ogura 1935, pp. 7–8.

- ^ George & Bachman 1934, pp. 22–33.

- ^ "By Authority". The Maui News. Wailuku. October 31, 1903. p. 3.

- ^ "Politics On Maui – 'Oily Bill' White Heads the List as Sheriff". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. September 28, 1903. p. 6.; "The result of the county election..." The Maui News. Wailuku. November 7, 1903. p. 3.; "Precinct Returns Of Maui County". Evening Bulletin. Honolulu. November 10, 1903. p. 3.; "Officials of Maui County". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. November 11, 1903. p. 1.; "County Government Starts". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. January 4, 1904. p. 5.; Thrum, Thomas G., ed. (1903). "Hawaiian Register and Directory for 1904". Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1904. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 243. hdl:10524/31853.

- ^ "Chronology of the Year 1903 (November 3)". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 1, 1904. p. 12.

- ^ "Governor Not Favorable". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. December 2, 1903. p. 2.

- ^ "The New Administration". The Maui News. Wailuku. January 9, 1904. p. 3.; "Maui Has Trouble". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 11, 1904. p. 3.

- ^ "Old Sheriffs Are Recalled". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 14, 1904. p. 4.

- ^ "Oily Bill Poured Oil On Political Waters". The Maui News. Wailuku. January 15, 1904. p. 1.; "The New Administration Is Pau". The Maui News. Wailuku. January 16, 1904. p. 3.; "Bill White Won't Give Up". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. January 15, 1904. p. 5.; "Maui Also Gives Up". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 18, 1904. p. 2.; "Maui Had Two Sheriffs – White Hit Hard by the Court's Decision". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. January 18, 1904. p. 3.

- ^ Menton & Tamura 1999, pp. 128–139.

- ^ "Safe, Sane And Conservative". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. October 1, 1906. p. 5.; "Complete Vote Of Maui County". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. November 8, 1906. p. 7.; "Election Returns, Maui County, Nov. 3, 1908". The Maui News. Wailuku. November 7, 1908. p. 1.; "Returns For The Island Of Oahu". The Hawaiian Star. Honolulu. November 9, 1910. p. 5.; "First Complete Election Returns From Oahu And Territory". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. November 6, 1912. p. 5.; "Detailed Precinct Returns Show Great Republican Strength". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. September 14, 1914. p. 8.; "Complete Primary Election Returns Shown For The Islands – Precinct Vote On Oahu Shows How New Nominating Method Worked". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. September 19, 1914. p. 11.

- ^ "May Extend The Limits – Liquor Licenses Issued This Year". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. November 18, 1901. pp. 9, 14.; "Kalei Nani Saloon". The Maui News. Wailuku. December 7, 1902. p. 2.; "Kalei Nani Saloon". The Maui News. Wailuku. January 24, 1903. p. 2.

- ^ Burial records of the Kaʻahumanu Society Cemetery

- ^ Williams 2011, p. 84.

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 300.

Bibliography

- Alexander, William DeWitt (1896). History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the Revolution of 1893. Honolulu: Hawaiian Gazette Company. OCLC 11843616.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allen, Helena G. (1982). The Betrayal of Liliuokalani: Last Queen of Hawaii, 1838–1917. Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0-87062-144-4. OCLC 9576325.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Andrade, Ernest (1996). Unconquerable Rebel: Robert W. Wilcox and Hawaiian Politics, 1880–1903. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado. pp. 99, 101, 104, 108, 113, 117, 202–203, 206, 215, 223. ISBN 978-0-87081-417-4. OCLC 247224388.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blount, James Henderson (1895). The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the Third Session of the Fifty-Third Congress, 1893–'94 in Thirty-Five Volumes. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 191710879.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chapin, Helen G. (2000). Guide to Newspapers of Hawaiʻi: 1834–2000. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. hdl:10524/1444. OCLC 45330644.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cushing, Robert L. (1985). Beginnings of Sugar Production in Hawaiʻi. Vol. 19. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. pp. 17–34. hdl:10524/508. OCLC 60626541.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Earle, David Williams (December 1993). "Coalition Politics in Hawaiʻi· 1887–90: Hui Kālaiʻāina and the Mechanics and Workingmen's Political Protective Union" (PDF). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/21097.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - George, William Henry; Bachman, Paul Stanton (1934). The Government of Hawaii, Federal, Territorial and County. Honolulu: University of Hawaii. OCLC 13513151.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hawaii (1918). Lydecker, Robert Colfax (ed.). Roster Legislatures of Hawaii, 1841–1918. Honolulu: Hawaiian Gazette Company. OCLC 60737418.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1874–1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty. Vol. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1. OCLC 500374815.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Liliuokalani (1898). Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Liliuokalani. Boston: Lee and Shepard. ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2. OCLC 2387226.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loomis, Albertine (1963). "The Longest Legislature" (PDF). Seventy-First Annual Report of the Hawaiian Historical Society for the Year 1962. 71. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 7–27. hdl:10524/35.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKinzie, Edith Kawelohea (1986). Stagner, Ishmael W. (ed.). Hawaiian Genealogies: Extracted from Hawaiian Language Newspapers. Vol. 2. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-939154-37-1. OCLC 12555087.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Menton, Linda K.; Tamura, Eileen (1999). A History of Hawaii, Student Book. Honolulu: Curriculum Research & Development Group. ISBN 978-0-937049-94-5. OCLC 49753910.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ogura, Shiku Ito (1935). County Government in Hawaii. Hilo, HI: Hawaii News Print Shop. OCLC 12499255.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Silva, Noenoe K. (2004). Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-8622-4. OCLC 191222123.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Twigg-Smith, Thurston (1998). Hawaiian Sovereignty: Do the Facts Matter? (PDF). Honolulu: Goodale Pub. ISBN 978-0-9662945-0-7. OCLC 39090004.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, Ronald, Jr. (May 2008). "ʻOnipaʻa Ka ʻOiaʻiʻo – Hearing Voices: Long Ignored Indigenous-Language Testimony Challenges The Current Historiography of Hawaiʻi Nei" (PDF). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/20822.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Williams, Ronald, Jr. (2011). "ʻIke Mо̄akaaka, Seeing a Path Forward: Historiography in Hawaiʻi" (PDF). Hūlili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being. 7. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools: 67–90. OCLC 906020258.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Williams, Ronald, Jr. (December 2013). "Claiming Christianity: The Struggle Over God and Nation in Hawaiʻi, 1880–1900" (PDF). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/42321.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Williams, Ronald, Jr. (2015). "Race, Power, and the Dilemma of Democracy: Hawaiʻi's First Territorial Legislature, 1901". The Hawaiian Journal of History. 49. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 1–45. OCLC 60626541 – via Project MUSE.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- "Journal of the House of Representatives, 1890". Ka Huli Ao Digital Archives.

- "Journal of the House of Representatives, 1892, Volume 1". Ka Huli Ao Digital Archives.

- "Journal of the House of Representatives, 1892, Volume 2". Ka Huli Ao Digital Archives.

- Journal of Proceedings of the House of Representatives – Regular and Extra Session of 1901 – First Legislature of the Territory of Hawaii. Honolulu: Bulletin Publishing Company. 1901. OCLC 819532926.

- First Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Hawaii, 1901 – Senate Journal – In Extra Session. Honolulu: The Grieve Publishing Company, Ltd. 1901. OCLC 12791672.

External links

Media related to William Pūnohu White at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Pūnohu White at Wikimedia Commons

- 1851 births

- 1925 deaths

- People from Lahaina, Hawaii

- Hawaii lawyers

- Newspaper editors

- Native Hawaiian politicians

- Kingdom of Hawaii politicians

- Members of the Kingdom of Hawaii House of Representatives

- Members of the Hawaii Territorial Legislature

- 20th-century American politicians

- National Reform Party (Hawaii) politicians

- Hawaiian National Liberal Party politicians

- Home Rule Party of Hawaii politicians

- Editors of Hawaii newspapers

- Hawaiian people of English descent

- Royal School (Hawaii) alumni

- Hawaiian insurgents and supporters

- Hawaii sheriffs