Opera house

An opera house is a theatre building used for opera performances that consists of a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and set building. While some venues are constructed specifically for operas, other opera houses are part of larger performing arts centers.

History

The first public opera house came into existence in 1637 as the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice, Italy, in a country where opera has been popular through the centuries among ordinary people as well as wealthy patrons; it still has a large number of working opera houses.[1] In contrast, there was no opera house in London when Henry Purcell was composing and the first opera house in Germany was built in Hamburg in 1678. Early United States opera houses served a variety of functions in towns and cities, hosting community dances, fairs, plays, and vaudeville shows as well as operas and other musical events.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, opera houses were often financed by rulers, nobles, and wealthy people who used patronage of the arts to endorse their political ambitions and social positions or prestige. With the rise of bourgeois and capitalist social forms in the 19th century, European culture moved away from its patronage system to a publicly supported system. In the 2000s, most opera and theatre companies raise funds from a combination of government and institutional grants, ticket sales, and private donations.

Features

The Teatro San Carlo in Naples introduces the plant horseshoe, the oldest in the world, a model for the Italian theater. On this model were built following theaters of Italy and Europe, among others, the court theater of the Palace of Caserta, who will become the model for other theaters. Given the popularity of opera in 18th and 19th century Europe, opera houses are usually large, with generally more than 1,000 seats and often several thousand. Traditionally, Europe's major opera houses built in the 19th century contained between about 1,500 to 3,000 seats, examples being Brussels' La Monnaie (after renovations, with 1,700 seats), Odessa Opera and Ballet Theater (with 1,636), Warsaw's Grand Theatre (the main auditorium with 1,841), Paris' Opéra Garnier (with 2,200), the Royal Opera House in London (with 2,268) and the Vienna State Opera (the new auditorium with reduced capacity of 2,280). Modern opera houses of the twentieth century such as New York's Metropolitan Opera (with 3,800) and the San Francisco Opera (with 3,146) are larger. Many operas are better suited to being presented in smaller theatres, such as Venice's La Fenice with about 1,000 seats.

In a traditional opera house, the auditorium is U-shaped, with the length of the sides determining the audience capacity. Around this are tiers of balconies, and often, nearer to the stage, are boxes (small partitioned sections of a balcony).

Since the latter part of the nineteenth century, opera houses generally have an orchestra pit, where a large number of orchestra players may be seated at a level below the audience, so that they can play without overwhelming the singing voices. This is especially true of Wagner's Bayreuth Festspielhaus where the pit is almost completely covered.

The size of an opera orchestra varies, but for some operas, oratorios and other works, it may be very large; for some romantic period works (or for many of the operas of Richard Strauss), it can be well over 100 players. Similarly, an opera may have a large cast of characters, chorus, dancers and supernumeraries. Therefore, a major opera house will have extensive dressing room facilities. Opera houses often have on-premises set and costume building shops and facilities for storage of costumes, make-up, masks, and stage properties, and may also have rehearsal spaces.

Major opera houses throughout the world often have highly mechanized stages, with large stage elevators permitting heavy sets to be changed rapidly. At the Metropolitan Opera, for instance, sets are often changed during the action, as the audience watches, with singers rising or descending as they sing. This occurs in the Met's productions of operas such as Aida and Tales of Hoffman. London's Royal Opera House, which was remodeled in the late 1990s, retained the original 1858 auditorium at its core, but added completely new backstage and wing spaces in addition to an additional performance space and public areas. Much the same happened in the remodeling of Milan's La Scala opera house between 2002 and 2004.

Although stage, lighting and other production aspects of opera houses often make use of the latest technology, traditional opera houses have not used sound reinforcement systems with microphones and loudspeakers to amplify the singers, since trained opera singers are normally able to project their unamplified voices in the hall. Since the 1990s, however, many opera houses have begun using a subtle form of sound reinforcement called acoustic enhancement (see below).

Often, operas are presented in their original languages, which may be different from the first language of the audience. For example, a Wagnerian opera presented in London may be in German. Therefore, since the 1980s modern opera houses have assisted the audience by providing translated supertitles, projections of the words above or near to the stage. More recently, electronic libretto systems have begun to be used in some opera houses, including New York's Metropolitan Opera, Milan's La Scala, and the Crosby Theatre of The Santa Fe Opera, which provide two lines of text on individual screens attached to the backs of the seats so as to not interfere with the visual aspects of the performance.

Acoustic enhancement with loudspeakers

A subtle type of sound reinforcement called acoustic enhancement is used in some opera houses. Acoustic enhancement systems help give a more even sound in the hall and prevent "dead spots" in the audience seating area by "...augment[ing] a hall's intrinsic acoustic characteristics." The systems use "...an array of microphones connected to a computer [which is] connected to an array of loudspeakers." However, as concertgoers have become aware of the use of these systems, debates have arisen, because "...purists maintain that the natural acoustic sound of [Classical] voices [or] instruments in a given hall should not be altered."[2]

Kai Harada [3] states that opera houses have begun using electronic acoustic enhancement systems "...to compensate for flaws in a venue's acoustical architecture." Despite the uproar that has arisen amongst operagoers, Harada points out that none of the opera houses using acoustic enhancement systems "...use traditional, Broadway-style sound reinforcement, in which most if not all singers are equipped with radio microphones mixed to a series of unsightly loudspeakers scattered throughout the theatre." Instead, most opera houses use the sound reinforcement system for acoustic enhancement, and for subtle boosting of offstage voices, onstage dialogue, and sound effects (e.g., church bells in Tosca or thunder in Wagnerian operas).

One example of the use of this kind of enhancement is the New York State Theater when it was used by the New York City Opera company.

Other uses of the term

In the 19th-century United States, many theaters were given the name "opera house," even ones where opera was seldom if ever performed. Opera was viewed as a more respectable art form than theater; calling a local theater an "opera house" therefore served to elevate it and overcome objections from those who found the theater morally objectionable.[4][5]

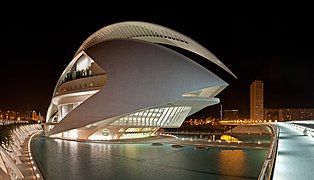

Gallery

-

Bayerisches Nationaltheater from 1818 in Munich, Bavaria, Germany; one of the world's most renowned opera houses, burnt down / reconstructed twice: 1823–25 and after WW II from 1958–63.

-

Bolshoi Theatre, in Moscow, Russia, is one of the world's most recognisable opera houses and home for the most famous ballet company in the world

-

The Cairo Opera House in Egypt

-

The Copenhagen Opera House in Denmark

-

The Sydney Opera House is one of the world's most recognizable opera houses and landmarks

-

The Berlin Staatsoper on Unter den Linden

-

The Alexandria Opera House in Alexandria, Egypt

-

Amazon Theatre in Manaus, Brazil

-

Theatro da Paz, Belém, Brazil

-

Ópera de Arame, Curitiba, Brazil

See also

References

Notes

- ^ BBC website

- ^ Kai Harada, "Why do you need a Sound System?", 2005

- ^ Kai Harada, "Opera's Dirty Little Secret", Entertainment Design website, Mar 1, 2001

- ^ Condee, William Faricy (2005). Coal and Culture: Opera Houses in Appalachia. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-8214-1588-3.

The term 'opera house' is indeed misleading, and intentionally so; it provides a veneer of social and cultural respectability and avoids the stigma of the title 'theater.'

- ^ "The Name Opera House". Dramatic Mirror. March 7, 1885.

Sources

- Allison, John (ed.), Great Opera Houses of the World, supplement to Opera Magazine, London 2003

- Beauvert, Thierry, Opera Houses of the World, The Vendome Press, New York, 1995. ISBN 0-86565-978-8

- Beranek, Leo. Concert Halls and Opera Houses: Music, Acoustics, and Architecture, New York: Springer, 2004. ISBN 0-387-95524-0

- Hughes, Spike. Great Opera Houses; A Traveller's Guide to Their History and Traditions, London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1956.

- Kaldor, Andras. Great Opera Houses (Masterpieces of Architecture) Antique Collectors Club, 2002. ISBN 1-85149-363-8

- Lynn, Karyl Charna, Opera: the Guide to Western Europe's Great Houses, Santa Fe, New Mexico: John Muir Publications, 1991. ISBN 0-945465-81-5

- Lynn, Karyl Charna, Italian Opera Houses and Festivals, Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-8108-5359-0

- Plantamura, Carol, The Opera Lover's Guide to Europe, Citadel Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8065-1842-1

- Sicca, Luigi Maria, "The management of opera houses: The Italian experience of the Enti Autonomi", Taylor & Francis, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 1997, ISSN 1028-6632