Marketing of electronic cigarettes

The marketing of e-cigarettes is legal in some jurisdictions, and spending is increasing rapidly.[2][3] It may or may not be regulated by existing laws on advertising for nicotine-containing products, recreational drugs, and medical drugs/devices. Controversially, some marketing for e-cigarettes uses false claims and now-banned techniques for marketing older nicotine-containing products.

Scale

In the United States, six large e-cigarette businesses spent $59.3 million on promoting e-cigarettes in 2013.[3] The use of e-cigarettes increased exponentially from 2004 to 2015.[2][4] However, from 2015 to 2016, e-cigarette use by US high school students dropped from 16 percent to 11.3%. Use of any nicotine product also declined, with 79.8% of high school students not using.[5][6]

Methods and claims

A 2014 review said, "the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s."[2] Many aspects of e-cigarette ads are familiar; like ads from the 1800 and 1900s, they show unrepresentatively healthy, well-dressed, high-status people. They may portray users as more popular and social (the ad illustrated here actually asserts that breaking a nicotine addiction will cause you to be disliked). They are likely to imply that users of their product are behaving in an adult manner, making free choices, rebelling against coercive authority, and expressing their identity as part of a group, their individuality and their independence; they are unlikely to mention nicotine addiction or other negative health effects. They also portray the product as an intelligent alternative to quitting for unwilling smokers, and make health claims.[8][9]: 62–63

E-cigarettes are marketed as a cheaper, more pleasant, and more convenient complement or alternative to smoking.[citation needed] Medical claims are also made, including "pharmaceuticalization", presenting e-cigarettes as medical or therapeutic devices,[10] claims formerly also made for combustible cigarettes.[9]: 62–64

Some often implicit marketing claims made both online and by some sales reps in vape shops are that[11][2]

- e-cigarettes are harmless, or even beneficial, to the user, compared with not smoking[12][11][1]

- e-cigarettes are harmless to others breathing the same air[2][13]

- e-cigarettes help smokers quit (weak evidence);[14][11] they are only, or mostly, used by smokers[7]

The evidence for these claims is weak to negative.[15] Nonsmokers are more likely to start vaping if they think e-cigarettes are not very harmful or addictive; beliefs about harmfullness and addiction don't affect the probability that smokers will start vaping.[16][17]

Addictiveness

As nicotine-containing products, e-cigarettes are highly addictive.[18] However, reference to the addictiveness of nicotine is avoided in marketing.[9]: 150

In a survey of American students in grades 6-12, only 33.8% said that they did not know whether e-cigarettes are more or less addictive than cigarettes; 31.2% believed that e-cigarettes were less addictive, and 5.4% believed that they were more addictive. Between 2012 and 2016, belief in the addictiveness (and harmfulness) of e-cigarettes fell among students, and the student's certainty in their beliefs grew. The survey authors attribute this partly to marketing, including youth-targeted advertisements and flavours.[17]

Some users have been unaware that e-cigarettes contain nicotine and are addictive.[19] Some e-fluids that labeled and marketed as containing no nicotine have been found to contain nicotine.[20][21]

Safety

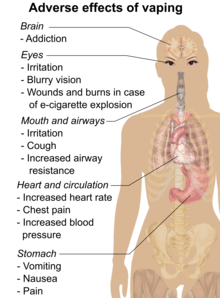

E-cigarettes and nicotine are regularly promoted as safe and beneficial in the media and on brand websites;[12] for instance, with the claim that e-cigarettes emit "only water vapor".[22] However, e-cigarette vapor contains other substances, such as nicotine, carbonyls, heavy metals, and organic volatile compounds, in addition to particulates.[22] It is plausible that vapourizing cigarettes may be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes,[7] but not that they are harmless. There is evidence of short-term harms (see image) and no evidence on the long-term health effects,[14] as e-cigarettes were introduced in 2004 and studies mostly run <12 months.[23]

It is commonly stated that the non-nicotine ingredients in an e-fluid are all deemed safe for food use. However, the Food and Drug Administration has stated that food ingredients it has approved (GRAS, "generally recognized as safe" ingredients) are only approved for eating: "GRAS status for a food additive does not mean that the substance is GRAS when inhaled, since GRAS status does not take inhalation toxicity into account."[11]

Harm to bystanders

E-cigarettes are sometimes marketed as harmless to bystanders. Apart from explicit claims, phrases such as "No second-hand smoke" and "No passive smoking" are also common.[13] Since the emissions of an e-cigarette are not classified by the marketer as smoke, but as vapour, this is technically true. However, the emissions are harmful to the health of people who are using or will use the same air. The World Health Organization's view regarding second hand aerosol (SHA) is "that while there are a limited number of studies in this area, it can be concluded that SHA is a new air contamination source for particulate matter, which includes fine and ultrafine particles, as well as 1,2-propanediol, some VOCs [volatile organic compounds], some heavy metals, and nicotine" and "[i]t is nevertheless reasonable to assume that the increased concentration of toxicants from SHA over background levels poses an increased risk for the health of all bystanders".[24] Public Health England has concluded that "international peer-reviewed evidence indicates that the risk to the health of bystanders from secondhand e-cigarette vapor is extremely low and insufficient to justify prohibiting e-cigarettes".[25] A systematic review concluded, "the absolute impact from passive exposure to EC [electronic cigarette] vapor has the potential to lead to adverse health effects. The risk from being passively exposed to EC vapor is likely to be less than the risk from passive exposure to conventional cigarette smoke."[26]

Claims of healthiness and safety are often made indirectly; for instance, a woman exhales into a baby carriage in a 2013 e-cigarette ad (for Flavor Vapes, UTVG, Inc.) reminiscent of early-twentieth-century cigarette ads.[27] Branding is used to imply healthiness, with brands named "Safe-cigs", "Lung Buddy", "iBreathe", and "E-HealthCigs".[13] Images of doctors are also used.[2]

"Smoke anywhere"

In some cases, marketing messages may also state or imply that users can "smoke anywhere" or need no longer go outside to satisfy nicotine cravings.[28][29] However, many jurisdictions prohibit vaping in some public places, and some ban them everywhere that tobacco cigarettes are banned.[29] As of 2014, vaping in enclosed public places is banned in 30 countries (containing 35% of the global population).[7]

Cessation aid

The promotion of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery systems] comes with at least one of the following messages or a combination of them: a) try to quit smoking and if everything fails use ENDS as the last resort; b) you do not need to quit nicotine addiction, just smoking; and c) you do not need to quit smoking, use ENDS where you cannot smoke. Some of these messages are difficult to harmonize with the core tobacco-control message ["tobacco use should not be started and if started it should be stopped"] and others are simply incompatible.

World Health Organisation report of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control[7]

There is no evidence that tobacco companies are selling e-cigarettes as part of a plan to phase out traditional cigarettes.[2] Most e-cigarettes are sold by manufacturers independent of traditional tobacco companies.

The evidence on the usefulness of e-cigarettes as a aid to breaking a nicotine addiction, or smoking less or no tobacco, is mixed. There are concerns that e-cigarette use may delay and deter quitting, perhaps partly by giving users an excuse to keep using nicotine.[2][4] E-cigarettes have been marketed at a reason not to quit.[30] Only one study comparing e-cigarettes to standard quitting methods has been published. Medical reviews have found both evidence that e-cigarettes increase the chance of quitting and evidence that they reduce the chance of quitting.[14][4]

A 2017 national survey of US e-cigarette users found that smokers were more likely to try to quit using e-cigarettes than using methods with stronger evidence of efficacy, such as talking to their doctor. Most smokers using e-cigarettes in quit attempts also continued to smoke ("dual use"). Dual use is not an effective harm reduction strategy.[31][32]

Use by non-smokers

E-cigarettes are marketed to people who have never smoked.[33] Such use is fairly common; in the US in 2015, 11.4% of adult users, and 40% of users aged 18-25, had never smoked tobacco cigarettes.[34] The World Health Organization is concerned about addiction of non-smokers.[7] Some of the common marketing messages detailed above have an influence on non-smokers, but not smokers: nonsmokers are more likely to start vaping if they think e-cigarettes are not very harmful or addictive; beliefs about harmfullness and addiction don't affect the probability that smokers will start vaping.[16][17]

Stress

E-cigarettes are advertised as good for stress reduction, mood, and insomnia.[35] This claim is true only for those addicted to nicotine, who need nicotine in order to feel normal. Nicotine products such as e-cigarettes temporarily relieve nicotine withdrawal symptoms (which include irritability, anxiety, stress, and depression). However, when people become addicted, they report worsening mood, and people who have broken a nicotine addiction report lasting improvements in mood.[36]

Dieting

E-cigarettes are also advertised as dieting aids. Nicotine may in fact be an appetite suppressant. However, getting addicted to nicotine in order to lose weight is widely discouraged by public health professionals.[37] There is much controversy concerning whether smokers are actually thinner than nonsmokers.[37] Some studies have shown that smokers—including long term and current smokers—weigh less than nonsmokers, and gain less weight over time.[38] Conversely, certain longitudinal studies have not shown correlation between weight loss and smoking.[39]

Cost

A common selling point it that e-cigarettes are cheaper than tobacco cigarettes. Costs of e-cigarettes vary widely by jurisdiction,[29] and high-end products may be more expensive.[11]

Celebrity product endorsements

Celebrity endorsements are also used to encourage e-cigarette use.[2][40] A national US television advertising campaign starred Steven Dorff exhaling a "thick flume" of what the ad describes as "vapor, not tobacco smoke", exhorting smokers with the message "We are all adults here, it's time to take our freedom back."[41] The ads, in a context of longstanding prohibition of tobacco advertising on TV, were criticized by organizations such as Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids as undermining anti-tobacco efforts.[41] Cynthia Hallett of Americans for Non-Smokers' Rights described the US advertising campaign as attempting to "re-establish a norm that smoking is okay, that smoking is glamorous and acceptable".[41] University of Pennsylvania communications professor Joseph Cappella stated that the setting of the ad near an ocean was meant to suggest an association of clean air with the nicotine product.[41]

Marketing targeting youth

"After having made tremendous progress in decreasing smoking rates, we may be now creating a new generation of nicotine addicts who will go on to be lifelong nicotine addicts, have difficulty stopping and perhaps start smoking regular cigs as well"

Dr. Benard Dreyer, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics[19]

E-cigarettes are marketed to young people[42] using cartoon characters and candy flavors,[43] and even claiming endorsement by Santa Claus,[44] in a re-use of older (now widely illegal) strategies used to promote chewing tobacco and cigarettes.[45][3][46] Some e-fluid has been sold packaged with candy and stickers.[47]

E-liquids made to look and smell like lollipops, pocky, sour candies, cookies, whipped cream, and fruit juice have faced regulatory action, partly because a child drinking as little as a few mL (less than one teaspoon) of the fluid could die from nicotine poisoning.[48][49][47][50]

Saying or suggesting that using a product is for adults only, or that an authority orders the target not to use it, or that using it is a way to rebel and be free, have been shown to be effective marketing strategies for persuading young people to use the product.[51]: 190–196 [52]

E-cigarettes are heavily promoted in the United States, mostly via the internet, as a healthy alternative to smoking.[53] E-cigarettes are widely marketed on social media, where age restrictions are often not implemented.[54][55][56] On Facebook, unpaid content, created and sponsored by tobacco companies, is widely used to advertise nicotine-containing products, with photos of the products, "buy now" buttons and a lack of age restrictions, in contravention of ineffectively enforced Facebook policies.[54][55][56] Both Google and Microsoft have policies that prohibit the promotion of tobacco products on their advertising networks.[57][58] However, some tobacco retailers are able to circumvent these policies by creating landing pages that promote tobacco accessories such as cigar humidors and lighters.[citation needed] Easily circumvented age verification at company websites enables young people to access and be exposed to marketing for e-cigarettes.[59]

Purchasing scams

A concentration on health regulation has led to a lack of action against purchasing scams. Some online dealers engages in marketing practises such as bait and switch, false "free trial" offers, automatic and uncancellable order renewals, recurring charges without notice, hidden fees, making it difficult to contact them, vanishing websites, and shipping defective or deficient products. The FTC has received about 600 consumer complaints against over 50 e-cigarette companies as of 2014. It has been recommended that consumers research merchants, read all the terms and conditions, and use a pre-paid credit card to avoid repeated and unwanted charges.[60]

Marketing regulation

While advertising of tobacco products is banned in most countries, and non-advertisment forms of marketing (such as stealth marketing) are regulated in some, fewer countries ban nicotine marketing. As of 2014, 39 countries containing 31% of the world's population have comprehensive e-cigarettes advertising, promotion and sponsorship bans, and 19 countries containing 5% of the world's populations in theory require products like e-cigarettes to be reviewed before being placed on the market.[7]

For regulatory purposes, e-cigarettes may be classified as

- A medical drug/device combination (if used to quit smoking, as an nicotine replacement therapy)

- A nicotine-containing product

- A tobacco product, or equivalent

- An addictive recreational drug

- A consumer product subject to false advertising legislation

In some countries, e-cigarettes may fall through the cracks, not being regulated under any existing legislation.[61]

E-cigarettes have been listed as drug delivery devices in several countries because they contain nicotine, and their advertising has been restricted until safety and efficacy clinical trials are conclusive.[62] Since they do not contain tobacco, television advertising in the United States is not restricted.[63] Some countries have regulated e-cigarettes as a medical product even though they have not approved them as a smoking cessation aid.[64]

Television and radio e-cigarette advertising in some countries may be indirectly encouraging traditional cigarette smoking.[2]

Some vendors have been fined for false advertising, mostly for misleading food and candy-like branding and false health claims or claims of medical endorsement, but also for selling mislabelled and contaminated e-fluid. Diethylene glycol[65] and diacetyl, which causes popcorn lung, have been found as contaminants. Some fluids that claim to contain no nicotine have also been found to contain nicotine.[66][21]

In 2016, e-cigarette companies fought not to have the health and safety of their products evaluated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, arguing that all existing products should be grandfathered in.[67]

In some jurisdictions, it is legal to market and sell e-cigarettes to minors.[3]

See also

References

- ^ a b See also a more cleanly-formatted version of this reference list on the Adverse effects of vaping on the separate page here, and the articles Health effects of tobacco and Nicotine addiction

- Brain

- Addiction "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Tobacco Control Program. California Department of Public Health. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Addiction "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Tobacco Control Program. California Department of Public Health. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2015.

- Eyes:

- Eye irritation Biyani, S; Derkay, CS (28 April 2015). "E-cigarettes: Considerations for the otolaryngologist". International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.032. PMID 25998217. and blurry visionBreland, Alison B.; Spindle, Tory; Weaver, Michael; Eissenberg, Thomas (2014). "Science and Electronic Cigarettes". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 8 (4): 223–233. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000049. ISSN 1932-0620. PMC 4122311. PMID 25089952.

- Corneoscleral lacerations or ocular burns after e-cigarette explosionPaley, Grace L.; Echalier, Elizabeth; Eck, Thomas W.; Hong, Augustine R.; Farooq, Asim V.; Gregory, Darren G.; Lubniewski, Anthony J. (2016). "Corneoscleral Laceration and Ocular Burns Caused by Electronic Cigarette Explosions". Cornea. 35 (7): 1015–1018. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000881. ISSN 0277-3740. PMC 4900417. PMID 27191672.

- Airways:

- Irritation and coughGrana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- Increased airway resistanceEbbert, Jon O.; Agunwamba, Amenah A.; Rutten, Lila J. (2015). "Counseling Patients on the Use of Electronic Cigarettes". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 25572196., Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- Irritation of the pharynxZborovskaya, Y (2017). "E-Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation: A Primer for Oncology Clinicians". Clin J Oncol Nurs. doi:10.1188/17.CJON.54-63. PMID 28107337.

- Stomach:

- Nausea and vomitingGrana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826., Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- Abdominal painBiyani, S; Derkay, CS (28 April 2015). "E-cigarettes: Considerations for the otolaryngologist". International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.032. PMID 25998217. and blurry visionBreland, Alison B.; Spindle, Tory; Weaver, Michael; Eissenberg, Thomas (2014). "Science and Electronic Cigarettes". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 8 (4): 223–233. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000049. ISSN 1932-0620. PMC 4122311. PMID 25089952.

- Heart and circulation:

- Chest painOrellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- Increased blood pressureOrellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- Increased heart rateOrellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- Mortality:

- Death after e-cigarette explosion (small risk)Paley, Grace L.; Echalier, Elizabeth; Eck, Thomas W.; Hong, Augustine R.; Farooq, Asim V.; Gregory, Darren G.; Lubniewski, Anthony J. (2016). "Corneoscleral Laceration and Ocular Burns Caused by Electronic Cigarette Explosions". Cornea. 35 (7): 1015–1018. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000881. ISSN 0277-3740. PMC 4900417. PMID 27191672.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- ^ a b c d "E-Cigarette use among children and young people: the need for regulation". Expert Rev Respir Med. 9: 1–3. 2015. doi:10.1586/17476348.2015.1077120. PMID 26290119.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Kalkhoran, Sara; Glantz, Stanton A (2016). "E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 4: 116–128. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00521-4. PMC 4752870. PMID 26776875.

- ^ McGinley, Laurie (2017-06-15). "Teenagers' tobacco use hits a record low, with a sharp drop in e-cigarettes". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ^ Jamal, Ahmed (2017). "Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6623a1. ISSN 0149-21951545-861X. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ a b c d e f g WHO. "Electronic nicotine delivery systems" (PDF). pp. 1–13. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st437.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img21854.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt053.php&theme_name=Smart,%20Pure%20&%20Fresh&subtheme_name=Smarter

- ^ a b c Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) of the Center for Tobacco Products of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2011-07-21). Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. p. 252. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Hendlin, Yogi Hale; Elias, Jesse; Ling, Pamela M. (2017-08-15). "The Pharmaceuticalization of the Tobacco Industry". Annals of internal medicine. 167 (4): 278–280. doi:10.7326/M17-0759. ISSN 0003-4819. PMC 5568794. PMID 28715843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b c d e "Vape Shops Clouding Issues of Safety". Truth In Advertising. 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ a b England, Lucinda J.; Bunnell, Rebecca E.; Pechacek, Terry F.; Tong, Van T.; McAfee, Tim A. (2015). "Nicotine and the Developing Human". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 49 (2): 286–93. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. ISSN 0749-3797. PMC 4594223. PMID 25794473.

- ^ a b c http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st387.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img17157.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt036.php&theme_name=Healthier&subtheme_name=Second%20Hand

- ^ a b c Hartman-Boyce, Jamie; McRobbie, Hayden; al, et (2016). "Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD010216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub3. PMID 27622384.

- ^ see individual per-bullet-point refs

- ^ a b Cooper, Maria; Loukas, Alexandra; Case, Kathleen R.; Marti, C. Nathan; Perry, Cheryl L. (2018). "A longitudinal study of risk perceptions and e-cigarette initiation among college students: Interactions with smoking status". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 186: 257–263. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.027. ISSN 1879-0046. PMC 5911205. PMID 29626778.

- ^ a b c Amrock, Stephen M.; Lee, Lily; Weitzman, Michael (2016-11-01). "Perceptions of e-Cigarettes and Noncigarette Tobacco Products Among US Youth". Pediatrics. 138 (5): –20154306. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-4306. ISSN 1098-4275 0031-4005, 1098-4275. PMID 27940754. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Tobacco Control Program. California Department of Public Health. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b CNN, Susan Scutti. "Surgeon general sounds the alarm on e-cigarettes". CNN. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Professionals: Educate Your Young Patients About the Risks of E-cigarettes (PDF), retrieved 2018-05-27

- ^ a b Food and drug Administration, Electronic Cigarettes, What is the bottom line (PDF), retrieved 2018-05-26 [:File:Electronic Cigarettes, What is the bottom line CDC.pdf fulltext on commons]

- ^ a b Fernández, Esteve; Ballbè, Montse; Sureda, Xisca; Fu, Marcela; Saltó, Esteve; Martínez-Sánchez, Jose M. (2015). "Particulate Matter from Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Cigarettes: a Systematic Review and Observational Study". Current Environmental Health Reports. 2: 423–9. doi:10.1007/s40572-015-0072-x. ISSN 2196-5412. PMID 26452675.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013-06), Tobacco: harm-reduction approaches to smoking (PDF), UK government

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ WHO (August 2016). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Electronic Non-Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS/ENNDS)" (PDF). pp. 1–11.

- ^ Public Health England. "E-cigarettes in public places and workplaces: a 5-point guide to policy making". uk.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Hess, IM; Lachireddy, K; Capon, A (15 April 2016). "A systematic review of the health risks from passive exposure to electronic cigarette vapour". Public health research & practice. 26 (2). doi:10.17061/phrp2621617. PMID 27734060.

- ^ A woman exhales from an e-cigarette into a baby carriage in this 2013 e-cigarette ad for Flavor Vapes (UTVG, Inc.)

- ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st367.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img16976.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt039.php&theme_name=Social%20Appeal&subtheme_name=Socializing

- ^ a b c Truth in Advertising (2015-09-01). "Smoking Out E-Cigarette Ad Claims". Truth In Advertising. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ see image in article, File:No-one_likes_a_quitter,_e-cigarette_ad.jpg

- ^ https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/index.htm

- ^ Caraballo, Ralph S.; Shafer, Paul R.; Patel, Deesha; Davis, Kevin C.; McAfee, Timothy A. (2017-04-13). "Quit Methods Used by US Adult Cigarette Smokers, 2014–2016". Preventing Chronic Disease. 14. doi:10.5888/pcd14.160600. ISSN 1545-1151. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ^ De, Andrade Marisa; Hastings, Gerard; Angus, Kathryn; Dixon, Diane; Purves, Richard (2013). "The marketing of electronic cigarettes in the uk".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/index.htm

- ^ http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st508.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img21920.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt065.php&theme_name=Health%20Giving&subtheme_name=Calming

- ^ Parrott, Andrew C. (2003-04). "Cigarette-derived nicotine is not a medicine". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry: The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. 4 (2): 49–55. ISSN 1562-2975. PMID 12692774.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Chiolero, A; Faeh, D; Paccaud, F; Cornuz, J (Apr 2008). "Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (4): 801–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. PMID 18400700.

- ^ Albanes, Demetrius, D. Yvonne Jones, Marc Micozzi, and Margaret E. Mattson, “Associations between Smoking and Body Weight in the US Population: Analysis of NHANES II,” American Journal of Public Health 77.4 (1987)

- ^ Nichter, Mimi, Mark Nichter, Nancy Vuckovic, laura Tesler, Shelly Adrian, and Cheryl Ritenbaugh, “Smoking as a Weight-Control Strategy among Adolescent Girls and Young Women: A Reconsideration,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 18.3 (2004): 307

- ^ Linda Bauld; Kathryn Angus; Marisa de Andrade (May 2014). "E-cigarette uptake and marketing" (PDF). Public Health England. pp. 1–19.

- ^ a b c d Daniel Nasaw (5 December 2012). "Electronic cigarettes challenge anti-smoking efforts". BBC News.

- ^ "E-cigarettes and Lung Health". American Lung Association. 2015.

- ^ "Myths and Facts About E-cigarettes". American Lung Association. 2015.

- ^ "E-Cigarettes Hitting Teen Targets?". Truth In Advertising. 2014-03-24. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ Laura Bach, "FLAVORED TOBACCO PRODUCTS ATTRACT KIDS", Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, (April. 2017)

- ^ http://adage.com/article/media/big-tobacco-spending-ads-e-cigarettes/241993/

- ^ a b "Warning Letters - Omnia E-Liquid 5/1/18" (WebContent). Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ "FTC, FDA Take Action Against Companies Marketing E-liquids That Resemble Children's Juice Boxes, Candies, and Cookies". Federal Trade Commission. 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ "FTC, FDA Warn Marketers of E-Liquids That Look Like Kids' Candy". Truth In Advertising. 2018-05-02. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ Affairs, Office of Regulatory. "2018 Warning Letters" (WebContent). Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ Davis, Ronald M.; Gilpin, Elizabeth A.; Loken, Barbara; Viswanath, K.; Wakefield, Melanie A. (2008). The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use (PDF). National Cancer Institute tobacco control monograph series. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. p. 684.

- ^ Grandpre, Joseph; Alvaro, Eusebio M.; Burgoon, Michael; Miller, Claude H.; Hall, John R. (2003-07). "Adolescent Reactance and Anti-Smoking Campaigns: A Theoretical Approach". Health Communication. 15 (3): 349–366. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1503_6. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rom, Oren; Pecorelli, Alessandra; Valacchi, Giuseppe; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2014). "Are E-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1340 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 25557889.

- ^ a b April 5, Ashley Welch CBS News; 2018; Pm, 5:02. "Facebook is used to promote tobacco, despite policies against it, study finds". Retrieved 2018-05-18.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jeter Hansen, Amy. "Tobacco products promoted on Facebook despite policies". News Center. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ a b Hansen, Author Amy Jeter (2018-04-05). "Despite policies, tobacco products marketed on Facebook, Stanford researchers find". Scope. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Advertising.microsoft.com. Advertising.microsoft.com (28 September 2011).

- ^ Adwords.google.com. Adwords.google.com.

- ^ ""Smoking revolution": a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites". Am J Prev Med. 46 (4): 395–403. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. PMC 3989286. PMID 24650842.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Consumers Getting Smoked by E-Cigs". Truth In Advertising. 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ https://www.morganlewis.com/pubs/fda-issues-first-e-cigarette-warning-letters

- ^ Cervellin, Gianfranco; Borghi, Loris; Mattiuzzi, Camilla; Meschi, Tiziana; Favaloro, Emmanuel; Lippi, Giuseppe (2013). "E-Cigarettes and Cardiovascular Risk: Beyond Science and Mysticism". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 40 (01): 060–065. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1363468. ISSN 0094-6176. PMID 24343348.

- ^ Maloney, Erin K.; Cappella, Joseph N. (2015). "Does Vaping in E-Cigarette Advertisements Affect Tobacco Smoking Urge, Intentions, and Perceptions in Daily, Intermittent, and Former Smokers?". Health Communication. 31: 1–10. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.993496. ISSN 1041-0236. PMID 25758192.

- ^ Bekki, Kanae; Uchiyama, Shigehisa; Ohta, Kazushi; Inaba, Yohei; Nakagome, Hideki; Kunugita, Naoki (2014). "Carbonyl Compounds Generated from Electronic Cigarettes". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (11): 11192–11200. doi:10.3390/ijerph111111192. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4245608. PMID 25353061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ FDAecigactions.pdf (PDF), retrieved 2018-05-26

- ^ Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Professionals: Educate Your Young Patients About the Risks of E-cigarettes (PDF), retrieved 2018-05-27

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/03/us/politics/e-cigarettes-vaping-cigars-fda-altria.html

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Biyani2015" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "EbbertAgunwamba2015" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Zborovskaya2017" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "BrelandSpindle2014" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "PaleyEchalier2016" is not used in the content (see the help page).