Timeline of peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori

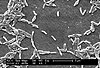

This is a timeline of the events relating to the discovery that peptic ulcer disease is caused by H. pylori. In 2005, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery that peptic ulcer disease (PUD) was primarily caused by Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium with affinity for acidic enivironments, such as the stomach. As a result, PUD that is associated with H. pylori is currently treated with antibiotics used to eradicate the infection. For 30 years prior to their discovery it was widely believed that PUD was caused by excess acid in the stomach. During this time, acid control was the primary method of treatment for PUD, to only partial success; among other effects, we now know that acid suppression alters the stomach milieu to make it less amenable to H. pylori infection.

Before the 1950s, there were many microbiological descriptions of bacteria in the stomach and in gastric acid secretions, lending credence to both the infective theory and the hyperacidity theory as being causes of peptic ulcer disease. A single study, conducted in 1954, did not find evidence of bacteria on biopsies of the stomach stained traditionally; this effectively established the acid theory as dogma. This paradigm was altered when Warren and Marshall effectively proved Koch's postulates for causation of PUD by H. pylori through a series of experiments in the 1980s; however, an extensive effort was required to convince the medical community of the relevance of their work. Now, all major gastrointestinal societies agree that H. pylori is the primary non-drug cause of PUD worldwide, and advocate its eradication as essential to treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Additionally, H. pylori has been associated with lymphomas and adenocarcinomas of the stomach, and has been classified by the World Health Organization as a carcinogen. Advances in molecular biology in the late twentieth century led to the sequencing of the H. pylori genome, resulting in a better understanding of virulence factors responsible for its colonization and infection, on the DNA level.

| Year | Events | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre 16th century |

|

|

| 1586 |

|

|

| 1688 |

| |

| 1728 | ||

| 1761 |

| |

| 1799 |

| |

| 1812 | ||

| 1821 |

| |

| 1822 |

| |

| 1868 |

| |

| 1875 | ||

| 1880 |

| |

| 1881 |

| |

| 1889 |

| |

| 1892 |

| |

| 1896 |

|

|

| 1905 |

| |

| 1906 | ||

| 1907 |

| |

| 1910 | ||

| 1913 |

|

|

| 1915 | ||

| 1919 |

| |

| 1921 |

| |

| 1924 | ||

| 1925 |

| |

| 1936 |

| |

| 1939 |

| |

| 1940 |

| |

| 1948 | ||

| 1951 |

|

|

| 1953 |

| |

| 1954 | ||

| 1955 |

| |

| 1957 | ||

| 1958 |

| |

| 1959 |

| |

| 1960 |

|

|

| 1962 |

| |

| 1964 |

| |

| 1966 |

| |

| 1967 |

| |

| 1968 |

| |

| 1971 |

| |

| 1972 |

| |

| 1974 | ||

| 1975 |

|

|

| 1978 |

| |

| 1979 |

|

|

| 1981 |

| |

| 1982 |

| |

| 1983 |

|

|

| 1984 |

| |

| 1985 |

| |

| 1987 |

| |

| 1990 |

| |

| 1992 |

| |

| 1994 |

|

|

| 1997 |

| |

| 2001 |

| |

| 2002 |

| |

| 2005 |

| |

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kidd, Mark (1998). "A century of Helicobacter pylori". Digestion. 59: 1–15. PMID 9468093.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Unge, Peter (2002). "Helicobacter pylori treatment in the past and in the 21st century". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 203–213. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ a b c Buckley, Martin J.M (1998). "Helicobacter biology - discovery". British Medical Bulletin. 54 (1): 7–16. PMID 9604426.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Fukuda, Yoshihiro (2002). "Kasai, Kobayashi and Koch's postulates in the history of Helicobacter pylori". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 1–13. ISBN 0867930357.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bizzozero, Giulio (1893). "Ueber die schlauchförmigen Drüsen des Magendarmkanals und die Beziehungen ihres Epitheles zu dem Oberflächenepithel der Schleimhaut". Archiv für mikroskopische Anatomie. 42: 82–152.

- ^ Figura, Natale (2002). "Helicobacters were discovered in Italy in 1892: An episode in the scientific life of an eclectic pathologist, Giulio Bizzozero.". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 1–13. ISBN 0867930357.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Turck, F.B. J.M (1906). "Ulcer of the stomach: Pathogenesis and pathology: Experiments in producing artificial gastric ulcer and genuine induced peptic ulcer". Journal of the American Medical Association. 46: 872.

- ^ Rosenow, E.C. J.M (1913). "The production of ulcer of the stomach by injection of streptococci". Journal of the American Medical Association. 61: 1947.

- ^ Rosenow, E.C. (1915). "The Bacteriology of Ulcer of the Stomach and Duodenum in Man". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 15: 219–226.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kasai, K. (1919). "The stomach Spirochete Occurring in Mammals". Journal of Parasitology (6): 1–11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Luck (1924). "Gastric Urease". Biochemical Journal. 37: 1227–1231.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hoffman, A (1925). "Experimental gastric duodenal inflammation and ulcer, produced with a specific organism fulfilling Koch's postulates". American Journal of Medical Science. 170: 212.

- ^ a b c d e Morozov, Igor A. "Helicobacter pylori was discovered in Russia in 1974". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 105–118. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ Freedberg, A. Stone. "=An Early Study of Human Stomach Bacteria". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 25–28. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ Doenges, James (1939). "Spirochaetes in the gastric glands of the Macaus Rhesus and Human without definite history of related disease". Archives of Pathology. 27: 469–477.

- ^ Freedberg, A.S. (1940). "The presence of spirochaetes in human gastric mucosa". American Journal of Digestive Diseases. 7: 443–445.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ O'Connor, Humphrey J. "Gastric urease in ulcer patients in the 1940s: The Irish connection". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 25–28. ISBN 0867930357.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dintzis, R.Z. (1953). "The effect of Antibiotics on Urea Breakdown in Mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 39: 571–8. PMID 16589306.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Palmer, E.D. (1954). "Investigation of the gastric mucosa spirochetes of the human". Gastroenterology. 27 (2): 218–220. PMID 13183283.

- ^ Kornberg, H.L. (1955). "Gastric Urease". Physiology Review. 35 (1): 169–177. PMID 14356931.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lieber, C.S. (1957). "Effect of oxytetracycline on acidity, ammonia, and urea in gastric juice in normal and uremic subjects". Comptes Rendus des Séances et Mémoires de la Société de Biologie. 151 (5): 1038–1042. PMID 13500735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Rigas, Basil. "John Lykoudis: The general practitioner in Greece who in 1958 discovered etiology of, and a treatment for, peptic ulcer disease". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 375–84. ISBN 0867930357.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lieber, Charles S. J. "How it was discovered in Belgium and the USA (1955-1976) that Gastric Urease was Caused by a Bacterial Infection". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 39–52. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ Lieber, C.S. (1959). "Ammonia as a source of gastric hypoacidity in patients with uremia". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 38: 1271–7. PMID 13673083.

{{cite journal}}: Text "issue8" ignored (help) - ^ Conway, E.J. (1959). "The location and origin of gastric urease". Gastroenterology. 37: 449–56. PMID 13811656.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vital, J.D. (1960). "Electron microscope observations on the fine structure of parietal cells". Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 7: 367–72. PMID 13842039.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Susser, M. (1962). "Civilization and peptic ulcer". Lancet. 1: 115–9. PMID 13918500.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). Reprinted as Susser M, Stein Z (2002). "Civilization and peptic ulcer. 1962". International Journal of Epidemiology. 31 (1): 13–7. PMID 11914283. - ^ Ito, Susumu (1967). "Anatomic structure of the gastric mucosa". In Heidel, US and Code, CF (ed.). Handbook of Physiology Section 6 Volume 2. American Physiological Society. pp. 705–741.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b Steer, Howard W. (2002). "The discover of Helicobacter pylori in England in the 1970s". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 119–129. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ a b c Xiao, Shu-Dong (2002). "How we discovered in China in 1972 that antibiotics cure peptic ulcer". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 165–202. ISBN 0867930357.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Patrick, W.J.A. (1974). "Mucous change in the human duodenum: a light and electron microscopic study and correlation with disease and gastric acid secretion". Gut. 15 (10): 767–76. PMID 4434919.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Steer, H.W. (1975). "Mucosal changes in gastric ulceration and their response to carbenoxolone sodium". Gut. 16 (8): 590–7. PMID 810394.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Peterson, Walter L. (2002). "The Dallas experience with acute Helicobacter pylori infection". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 143–150. ISBN 0867930357.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramsey, E.J. (1979). "Epidemic gastritis with hypochlorhydria". Gastroenterology. 76 (6): 1449–57. PMID 437444.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, J. Robin (2002). "The discovery of Helicobacter pylori in Perth, Western Australia". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 165–202. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ Fung, W.P. (1979). "Endoscopic, histological and ultrastructural correlations in chronic gastritis". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 71 (3): 269–79. PMID 443229.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Marshall, Barry (2002). "The discovery that Helicobacter pylori, a spiral bacterium, caused peptic ulcer disease.". In Barry Marshall (ed.). Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand Accounts from the Scientists Who Discovered Helicobacters. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Science Asia. pp. 165–202. ISBN 0867930357.

- ^ Satoh, H. (1983). "Role of bacteria in gastric ulceration produced by indomethacin in the rat: cytoprotective action of antibiotics". Gastroenterology. 84 (3): 483–9. PMID 6822322.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, J.R. (1983). "Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis". Lancet. 1 (8336): 1273–5. PMID 6134060.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McNulty, C.A. (1984). "Spiral bacteria of the gastric antrum". The Lancet. 1 (8385): 1068–9. PMID 6143990.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Morris, A. (1987). "Ingestion of Campylobacter pyloridis causes gastritis and raised fasting gastric pH". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 82 (3): 192–9. PMID 3826027.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Coghlan, J.G. (1987). "Campylobacter pylori and recurrence of duodenal ulcers—a 12-month follow-up study". The Lancet. 2 (8568): 109–11. PMID 2890019.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rauws E, Tytgat G (1990). "Cure of duodenal ulcer associated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori". Lancet. 335 (8700): 1233–5. PMID 1971318.

- ^ Rauws, E.A.J. (1990). "Cure of duodenal ulcer associated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori". The Lancet. 335 (8700): 1233–5. PMID 1971318.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Becx M, Janssen A; et al. (1990). "Metronidazole-resistant Helicobacter pylori". Lancet. 335 (8688): 539–40. PMID 1968548.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, O'Morain C; et al. (2002). "Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 16 (2): 167–80. PMID 11860399.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Covacci A, Censini S, Bugnoli M; et al. (1993). "Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 90 (12): 5791–5. PMID 8516329.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "IARC Monograph on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans". Lyon: World Health Organization: 177–240. 1994.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L; et al. (1994). "Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 330 (18): 1267–71. PMID 8145781.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tomb J, White O, Kerlavage A; et al. (1997). "The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori". Nature. 388 (6642): 539–47. PMID 9252185.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aspholm-Hurtig M, Dailide G, Lahmann M; et al. (2004). "Functional adaptation of BabA, the H. pylori ABO blood group antigen binding adhesin". Science. 305 (5683): 519–22. PMID 15273394.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chan F, Chung S, Suen B; et al. (2001). "Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low-dose aspirin or naproxen". N Engl J Med. 344 (13): 967–73. PMID 11274623.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nobel Prize in Medicine 2005". Nobel Foundation.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- Barry J. Marshall (2001). "One hundred years of discovery and rediscovery of Helicobacter pylori and its association with peptic ulcer disease". Chapter 3 of Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics ed. by Harry L. T. Mobley, George L. Mendz, and Stuart L. Hazell. ASM Press. ISBN 1-55581-213-9.