Rabbit hemorrhagic disease

A request that this article title be changed is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

| Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus | |

|---|---|

| |

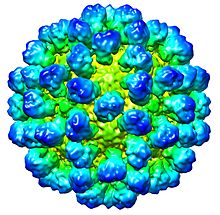

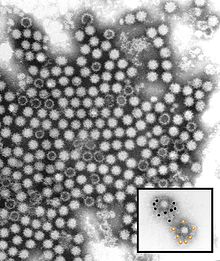

| CryoEM reconstruction of the virus capsid. EMDB entry EMD-1933[2] | |

| Virus classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus |

| Isolates[1] | |

| |

Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD), also known as viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD), is a highly infectious and lethal form of viral hepatitis that affects European rabbits. Some viral strains also affect hares and cottontail rabbits. Mortality rates generally range from 70 to 100 percent.[3] The disease is caused by strains of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV), a lagovirus in the family Caliciviridae.

RHDVa and RHDV-2

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease viruses (RHDV) are single strand RNA viruses in the genus Lagovirus and the family Caliciviridae. In the course of its evolution RHDV split into six distinct genotypes,[4] all of which are highly pathogenic. In addition, non-pathogenic rabbit caliciviruses related to but distinct from RHDV have been identified in Europe and Australia.[5] Rabbit lagoviruses also include related caliciviruses such as European brown hare syndrome virus.[6]

The two strains of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus currently of medical significance are RHDVa and RHDV-2. RHDVa (also referred to as RHDV, RHDV1, or as classical RHD) only affects adult European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). This virus was first reported in China in 1984,[7] from which it spread to much of Asia, Europe, Australia, and elsewhere.[8] There have been a few isolated outbreaks of RHDVa in the United States and Mexico, but they remained localized and were eradicated.

In 2010, a new lagovirus with a distinct antigenic profile was identified in France. This virus also caused rabbit haemorrhagic disease but behaved differently from RHDVa in that it affected vaccinated and young European rabbits as well as hares (Lepus spp.).[3] All these features strongly suggested that the virus was not derived from RHDVa but from some other unknown source.[3] The new virus was named rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (abbreviated as RHDV-2 or RHDVb). RHDV-2 is distinct enough from RHDVa that the two require different vaccines, which are only partially cross protective. RHDV-2 has since spread to the majority of Europe as well as to Australia, Canada, and the United States.

Epidemiology and transmission

Both viruses causing RHD are extremely contagious. Transmission occurs by direct contact with infected animals, carcasses, bodily fluids (urine, feces, respiratory secretions), and hair. Surviving rabbits may be contagious for up to 2 months.[6] Contaminated fomites such as clothing, food, cages, bedding, feeders and water also spread the virus. Flies, fleas, and mosquitoes can carry the virus between rabbits.[8] Predators and scavengers can also spread the virus by shedding it in their feces.[8] Caliciviruses are highly resistant in the environment, and can survive freezing for prolonged periods. Virus can persist in infected meat for months, and for prolonged periods in decomposing carcasses. Importation of rabbit meat may be a major contributor in the spread of the virus to new geographic regions.[6]

RHD outbreaks tend to be seasonal in wild rabbit populations, where most adults have survived infection and are immune. As young kits grow up and stop nursing, they no longer receive the antibodies provided in their mother's milk and become susceptible to infection. Thus RHD epizootics occur more often during the rabbits' breeding season.[8]

There is generally high host specificity among lagoviruses.[6] Classic RHDVa only affects European rabbits, a species native to Europe and from which the domestic rabbit is descended. The new variant RHDV-2 affects European rabbits as well but also causes fatal RHD in various Lepus species, including Sardinian Cape hares (Lepus capensis mediterraneus), Italian hares (Lepus corsicanus) and mountain hares (Lepus timidus). [9] Reports of RHD in Sylvilagus species have been coming from the current outbreak in the United States.[10]

RHD caused by classic RHDVa demonstrates high morbidity (up to 100%) and mortality (70-90%) in adult European rabbits. Young rabbits that are 6-8 weeks old are less likely to be infected, and kits younger than 4 weeks old do not become ill.[6] The more recently emerged RHDV-2 causes death and disease in rabbits as young as 15 to 20 days old. Mortality rates from RHDV-2 were initially only 20-30%, but over time the virulence of the strain has been increasing and is now similar to that found with RHDVa. Deaths from RHDV-2 have been confirmed in rabbits previously vaccinated against RHDVa.[6]

Pathophysiology

Both viral strains of RHDV replicate in the liver, causing hepatic necrosis and liver failure. Liver failure can in turn lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic encephalopathy, and nephrosis.[8] Bleeding may occur as clotting factors and platelets are used up.

Clinical signs

Rabbit haemorrhagic disease causes hepatitis. The incubation period for RHDVa is one to two days, and for RHDV-2 three to five days. Rabbits infected with RHDV-2 are more likely to show subacute or chronic signs than are those infected with RHDVa.[6] In rabbitries, an epidemic with high mortality rates in adult and subadult rabbits is typical.[8] If the outbreak is caused by RHDV-2 than deaths will also occur in young rabbits.

RHD can vary in how quickly or slowly clinical signs occur. In peracute cases rabbits are usually found dead with no premonitory symptoms.[9] Rabbits may be observed grazing normally immediately before death.[8]

In acute cases rabbits are inactive and reluctant to move. They may develop a fever of up to 42° C (107.6° F) and have increased heart and respiratory rates. Bloody discharge from the nose, mouth, or vulva is common, as is blood in the feces or urine. Lateral recumbency, coma, and convulsions may be observed before death.[8] Rabbits with the acute form generally die within 12 to 36 hours from the onset of fever.[9]

Subacute to chronic RHD has a more protracted clinical course, and is more commonly noted with RHDV-2 infections. Clinical signs include lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, and jaundice. Gastrointestinal dilation, cardiac arrhythmias, heart murmurs, and neurologic abnormalities can also occur.[6] Death, if it occurs, usually happens 1 to 2 weeks after the onset of symptoms, and is due to liver failure. [9]

Not all rabbits exposed to RHDVa or RHDV-2 become overtly ill. A small proportion of infected rabbits clear the virus without developing signs of disease.[8] Asymptomatic carriers also occur, and can continue to shed virus for months, thereby infecting other animals. Surviving rabbits develop a strong immunity to the specific viral variant they were infected with.[6]

Diagnosis

A presumptive diagnosis of RHD can often be made based on clinical presentation, infection pattern within a population, and post-mortem lesions. Definitive diagnosis requires detection of the virus. As most caliciviruses cannot be grown in cell culture, molecular and serologic methods of viral detection are often used.[6]

Complete blood counts from rabbits with RHD often show low levels of white blood cells and platelets, and chemistry panels show elevated liver enzymes. Evidence of liver failure may also be present, including increased bile acids and bilirubin, and decreased glucose and cholesterol. Prolonged prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times are typical. Urinalysis can show bilirubinuria, proteinuria, and high urinary GGT.[6]

The classic postmortem lesion seen in rabbits with RHD is extensive hepatic necrosis and jaundice. There may also be multifocal hemorrhages, splenomegaly, bronchopneumonia, pulmonary hemorrhage or edema, and myocardial necrosis. [6]

A variety of molecular tests can be used to identify RHD viruses. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests are a commonly used and accurate testing modality for viruses. Other tests used include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), electron microscopy, immunostaining, Western blot, and in situ hybridization.[6] The tissue of choice for molecular testing is fresh or frozen liver, as it usually contains the largest amount of virus, but if this is not available spleen and serum can also be used. It is important to identify the strain of RHDV so that vaccination protocols can be adjusted accordingly.

Prevention and control

Vaccines

There are a number of vaccines available against RHD that are sold in countries where the disease is endemic. All last for 12 months and contain inactivated strains of RHDV.

Vaccines against only the classic RHDVa strain are as follows: Cylap® RCD Vaccine, made by Fort Dodge Animal Health,[11] protects rabbits from two different strains of RHDVa (v351 and K5) that are used for wild rabbit control in Australia.[12] CUNIPRAVAC RHD®,[13] manufactured by HIPRA, protects against the RHDVa strains found in Europe. Nobivac Myxo-RHD,[14] made by MSD Animal Health, is a live myxoma-vectored vaccine that offers one year duration of immunity against both RHDVa and myxomatosis.

Vaccines against only the newer RHDV-2 strain are as follows: Eravac® vaccine, manufactured by HIPRA,[15] protects rabbits against RHDV-2 for one year.

Vaccines that protect against both RHDVa and RHDV-2 strains are as follows: FILAVAC VHD K C+V®,[16] manufactured by Filavie, protects against both classical RHDVa and RHDV-2.[17] It is available in single dose as well as multidose vials. A soon to be released vaccine from MSD Animal Health, Nobivac Myxo-RHD PLUS®, is a live recombinant vector vaccine active against both RHDVa and RHDV-2, as well as myxomatosis.[18]

Countries in which RHD is not considered endemic may place restrictions on importation of RHDV vaccines. Importation of these vaccines into the United States can only be done with the approval of the United States Department of Agriculture[19] and the appropriate state veterinarian.[20]

Quarantine and other measures

Because of the highly infectious nature of the disease, strict quarantine is necessary when outbreaks occur. Depopulation, disinfection, vaccination, surveillance and quarantine are the only way to properly and effectively eradicate the disease. Good disinfectants include 10% sodium hydroxide, 1-2% formalin, 2% One-Stroke Environ, and 10% household bleach. The RHD virus is resistant to ethers and chloroform. Deceased rabbits must be removed immediately and discarded in a safe manner. Surviving rabbits should be quarantined or humanely euthanized. Test rabbits may be used to monitor the virus on vaccinated farms.[21]

Geographic distribution

RHD was first reported in 1984 in The People's Republic of China, and two years later in Europe. To date, RHD has been reported in over 40 countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania, and is endemic in most parts of the world.[22]

Asia

The first reported outbreak of rabbit haemorrhagic disease caused by RHDVa occurred in 1984 in the Jiangsu Province of the People's Republic of China.[7] The outbreak occurred in a group of Angora rabbits that had been imported from Germany. The cause of the disease was determined to be a small non-enveloped RNA virus. An inactivated vaccine was developed that proved effective in preventing disease.[7] In less than a year, the disease spread over an area of 50,000 square kilometers in China and killed 140 million domestic rabbits.[23]

South Korea was the next country to report RHD outbreaks following the importation of rabbit fur from China.[23][24] RHD has since spread to and become endemic in many countries in Asia, including India and the Middle East.

Europe

From China, RHDVa spread westward to Europe. The first report of RHD in Europe came from in Italy in 1986.[23] From there it spread to much of Europe. Spain's first reported case was in 1988,[23] and France, Belgium, and Scandinavia followed in 1990. Spain experienced a large die-off of wild rabbits, which in turn caused a population decline in predators that normally ate rabbits, including the Iberian lynx and Spanish imperial eagle.[25][26]

RHD caused by RHDVa was reported for the first time in the United Kingdom in 1992.[27] This initial epidemic was brought under control in the late 1990s using a combination of vaccination, strict biosecurity, and good husbandry.[9] The newer viral strain RHDV-2 was first detected in England and Wales in 2014, and soon spread to Scotland and Ireland.[9]

In 2010, a new virus variant called rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (RHDV-2) emerged in France.[28] RHDV-2 has since spread from France to the rest of Europe, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand. Outbreaks of RHDV-2 started occurring in the United States and Vancouver Island Canada in 2019. In 2020, RHDV-2 has been reported in Washington State, New York, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Texas.

RHD was detected for the first time in Finland in 2016. The outbreak occurred in feral European rabbits, and genetic testing identified the viral strain as RHDV-2. Cases of viral transmission to domesticated pet rabbits have been confirmed, and vaccinating rabbits has been recommended.[29]

Australia

In 1991 a strain of the RHDVa virus, Czech CAPM 351RHDV, was imported to Australia[30] under strict quarantine conditions to research the safety and usefulness of the virus if it was used as a biological control agent against Australia and New Zealand's rabbit pest problem. Testing of the virus was undertaken on Wardang Island in Spencer Gulf off the coast of the Yorke Peninsula, South Australia. In 1995 the virus escaped quarantine and subsequently killed 10 million rabbits within 8 weeks of its release.[31]

In March 2017 a new Korean strain known as RHDV K5 was successfully released in a deliberate manner after almost a decade of research. This strain was chosen in part because it functions better in cool, wet regions where the previous Calicivirus was less effective.[32]

New Zealand

In July 1997, after considering over 800 public submissions, the New Zealand Ministry of Health decided not to allow RHDVa to be imported into New Zealand to control rabbit populations. This was backed up in an early August review of the decision by the Director-General of Agriculture. However, in late August it was confirmed that RHDVa had been deliberately and illegally introduced to the Cromwell area of the South Island. An unsuccessful attempt was made by New Zealand officials to control the spread of the disease. It was, however, being intentionally spread, and several farmers (notably in the Mackenzie Basin area) admitted to processing rabbits that had died from the disease in kitchen blenders for further spreading.

Had the disease been introduced at a better time, there would have been a more effective control of the population. However, it was released after breeding had commenced for the season, and rabbits under 2 weeks old at the time of the introduction were resistant to the disease. These young rabbits were therefore able to survive and breed rabbit numbers back up. Ten years on, rabbit populations (in the Mackenzie Basin in particular) are beginning to reach near pre-plague proportions once again though they have not yet returned to pre RCD levels.[33][34]

Resistance to RHD in New Zealand rabbits has led to the widespread use of Compound 1080 (Sodium fluoroacetate). The Government and department of Conservation are having to increase their use of 1080 to protect Reserve land from rabbits and preserve the gains made in recent years through the use of RHD.[35]

North and South America

Isolated outbreaks of RHDVa in domestic rabbits have occurred in the United States, the first of which was in Iowa in 2000.[36] In 2001 outbreaks occurred in Utah, Illinois, and New York.[37][38][39]) More recent outbreaks of RHDVa have occurred in 2005 in Indiana, and 2018 in Pennsylvania.[40][41]). Each of these outbreaks was contained and was the result of separate but indeterminable introductions of RHDVa.[8] RHDVa does not affect the native cottontail and jackrabbits in the United States, and so the virus did not become endemic.[21]

The first report of RHDV-2 virus in North America was on a farm in Québec, Canada, in 2016. In 2018 a larger outbreak occurred in feral European rabbits on Delta and Vancouver Islands, Canada.[42] The disease was confirmed later that year in a pet rabbit in Ohio.[43] In July 2019, the first case of RHDV-2 in Washington State was confirmed in a pet rabbit from Orcas Island[44] In 2020, outbreaks of RHD have been reported in Washington state, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, and New York. The source of these outbreaks is unknown.[45] The outbreak in the Southwest is affecting wild jackrabbit and cottontail populations as well as domestic pet species.[46] This outbreak is spreading, and is unlikely to be contained.

Mexico experienced an outbreak RHDVa in domestic rabbits from 1989 to 1991, presumably following the importation of rabbit meat from the People's Republic of China.[47] Strict quarantine and depopulation measures were able to eradicate the virus.[21] A second outbreak of RHD in domestic rabbits began in the state of Chihuahua in April of 2020 and is ongoing; the viral strain responsible has yet to be determined. However, reports of dead wild rabbits in the vicinity makes it likely to be RHDV-2.[48]

Since 1993, RHDVa has been endemic in Cuba. Four epizootics involving domesticated rabbits were reported in 1993, 1997, 2000-2001 and 2004-2005. As consequence, thousands of rabbits have died or have been slaughtered each time.[49] The virus is also believed to be thriving in Bolivia.

See also

References

- ^ "ICTV 9th Report (2011) Caliciviridae" (html). International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Luque, D; González, JM; Gómez-Blanco, J; et al. (2012). "Epitope Insertion at the N-Terminal Molecular Switch of the Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus T=3 Capsid Protein Leads to Larger T=4 Capsids". Journal of Virology. 86 (12): 6470–6480. doi:10.1128/JVI.07050-11.

- ^ a b c Capucci, L; Cavadini, P; Schiavitto, M; et al. (29 April 2017). "Increased pathogenicity in rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (RHDV2)". Veterinary Record. 180 (17): 426. doi:10.1136/vr.104132.

- ^ Kerr, PJ; Kitchen, A; Holmes, EC (16 September 2009). "Origin and Phylodynamics of Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus". Journal of Virology. 83 (23): 12129–12138. doi:10.1128/JVI.01523-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Capucci, L; Fusi, P; Lavazza, A; et al. (December 1996). "Detection and preliminary characterization of a new rabbit calicivirus related to rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus but nonpathogenic". Journal of Virology. 70 (12): 8614–8623.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gleeson, M; Petritz, OA (May 2020). "Emerging Infectious Diseases of Rabbits". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 23 (2): 249–261. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2020.01.008.

- ^ a b c Liu, SJ; Xue, HP; Pu, BQ; et al. (1984). "A new viral disease in rabbits". Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine (Xumu yu Shouyi). 16 (6): 253–255.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kerr, Peter J.; Donnelly, Thomas M. (May 2013). "Viral Infections of Rabbits". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (2): 437–468. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.02.002.

- ^ a b c d e f Rocchi, Mara S.; Dagleish, Mark P. (27 January 2018). "Diagnosis and prevention of rabbit viral haemorrhagic disease 2". In Practice. 40 (1): 11–16. doi:10.1136/inp.k54.

- ^ "Southwest US faces lethal rabbit disease outbreak". Veterinary Information Network. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "Cylap® RCD Vaccine". www.zoetis.com.au. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Read, AJ; Kirkland, PD (July 2017). "Efficacy of a commercial vaccine against different strains of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus". Australian Veterinary Journal. 95 (7): 223–226. doi:10.1111/avj.12600.

- ^ "CUNIPRAVAC RHD". HiPRA. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Nobivac Myxo RHD® | Overview". MSD Animal Health. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Eravac". NOAH Compendium. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "FILAVAC VHD K C+V". NOAH Compendium. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Le Minor, O.; Boucher, S.; Joudou, L.; Mellet, R.; Sourice, M.; Le Moullec, T.; Nicolier, A.; Beilvert, F.; Sigognault-Flochlay, A. (2019). "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease: experimental study of a recent highly pathogenic GI.2/RHDV2/b strain and evaluation of vaccine efficacy". World Rabbit Science. 27 (3): 143. doi:10.4995/wrs.2019.11082.

- ^ "Nobivac Myxo-RHD PLUS". NOAH Compendium. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "APHIS Form 2005" (PDF). USDA APHIS. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "State Animal Health Officials" (PDF). USAHA. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Spickler, Anna. "Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease" (PDF). The Center for Food Security and Public Health. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease" (PDF). OIE Technical Disease Cards. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Abrantes, J; van der Loo, W; Le Pendu, J; Esteves, PJ (10 February 2012). "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV): a review". Veterinary Research. 43: 12. doi:10.1186/1297-9716-43-12. PMC 3331820. PMID 22325049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lee, Cha Soo; Park, Cheong Kyu; Shin, Tae Kyun; Cho, Yong Joon; Jyeong, Jong Sik (1990). "An outbreak of rabbit sudden death in Korea suspected of a new viral hepatitis". The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science. 52 (5): 1135–1137. doi:10.1292/jvms1939.52.1135.

- ^ "Iberian Lynx Depends On Rabbits for Survival". Science Daily. 5 July 2011.

- ^ Platt, John R. (12 July 2011). "Deadly Rabbit Disease May Have Doomed Iberian Lynx". Scientific American.

- ^ Chasey, D. (1994). "Possible origin of rabbit haemorrhagic disease in the United Kingdom". Veterinary Record. 135 (21): 469–499.

- ^ Le Gall-Reculé, Ghislaine; Lavazza, Antonio; Marchandeau, Stéphane; Bertagnoli, Stéphane; Zwingelstein, Françoise; Cavadini, Patrizia; Martinelli, Nicola; Lombardi, Guerino; Guérin, Jean-Luc (2013-09-08). "Emergence of a new lagovirus related to rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus". Veterinary Research. 44 (1): 81. doi:10.1186/1297-9716-44-81. PMC 3848706. PMID 24011218.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Isomursu, Marja; Neimanis, Aleksija; Karkamo, Veera; Nylund, Minna; Holopainen, Riikka; Nokireki, Tiina; Gadd, Tuija (October 2018). "An Outbreak of Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease in Finland". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 54 (4): 838–842. doi:10.7589/2017-11-286.

- ^ Cooke, Brian Douglas (2014). Australia's War Against Rabbits. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9780643096127.

- ^ Strive, Tanja (16 July 2008). "Rabbit Calicivirus Disease (RCD)". Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. Archived from the original (pdf) on April 15, 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Adams, Prue (1 April 2017). "K5 rabbit virus an early success, researchers say". ABC News. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ Munro, Robert K.; Williams, Richard T., eds. (1994). Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease: Issues in Assessment for biological control. Canberra: Bureau of Resource Sciences. ISBN 9780644335126.

- ^ Williams, David (26 May 2009). "Plan for 1080 drops in MacKenzie Basin". The Press. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ "Welcome to 1080: The Facts". 1080facts.co.nz. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ "Rabbit calicivirus infection confirmed in Iowa rabbitry". www.avma.org. American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Viral Hemorrhagic Disease of Rabbits_ Utah 8_28_01". www.aphis.usda.gov. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Campagnolo, Enzo R.; Ernst, Mark J.; Berniger, Mary L.; Gregg, Douglas A.; Shumaker, Thomas J.; Boghossian, Aida M. (October 2003). "Outbreak of rabbit hemorrhagic disease in domestic lagomorphs". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 223 (8): 1151–5. doi:10.2460/javma.2003.223.1151.

- ^ "Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease (Calicivirus) in the US" (PDF). AgLearn. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease_ Indiana". www.aphis.usda.gov. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease, United States of America (Jefferson County, Pennsylvania report)". OiE. World Organization for Animal Health. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Rabbit hemorrhagic disease in British Columbia, Canada" (PDF). USDA. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "First report of Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Type 2 In US found in Ohio". Ohio Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ McGann, Chris (19 June 2019). "Deadly rabbit disease confirmed on Orcas Island" (Press release). Olympia, WA: Washington State Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease, United States of America". www.oie.int. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Cause for Rabbit Mortality". New Mexico Department of Game & Fish. 7 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Gregg, D.A.; House, C.; Berninger, M. (1 June 1991). "Viral haemorrhagic disease of rabbits in Mexico : epidemiology and viral characterization". Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 10 (2): 435–451. doi:10.20506/rst.10.2.556.

- ^ "Rabbit haemorrhagic disease, Mexico". OIE. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Farnós, O; Fernández, E; Chiong, M; et al. (2009). "Virus-like particles of the Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus obtained in yeast are able to induce protective immunity against classical strains and a viral subtype circulating in Cuba". Biotecnología Aplicada. 26 (3).

- New outbreak in Canada reported on Vancouver Island "B.C. Issues warning to pet rabbit owners as virus spreads to Lower Mainland | CBC News".