Lerone Bennett Jr.: Difference between revisions

→External links: commons category added |

minor c/e, tweaks to refs |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

===Early life and education=== |

===Early life and education=== |

||

Bennett was born in [[Clarksdale, Mississippi]], on October 17, 1928, the son of Lerone Bennett Sr. and Alma Reed. When he was young, his family moved to [[Jackson, Mississippi]], the capital. His father worked as a chauffeur and |

Bennett was born in [[Clarksdale, Mississippi]], on October 17, 1928, the son of Lerone Bennett Sr. and Alma Reed. When he was young, his family moved to [[Jackson, Mississippi|Jackson]], Mississippi, the capital. His father worked as a chauffeur and.his mother was a maid but they divorced when he was a child. At twelve he began writing for ''[[The Mississippi Enterprise]]'', a Jackson, Mississippi, black owned paper. He recalled once getting in trouble for being distracted from an errand when he happened upon a newspaper to read. He attended segregated schools as a child under the state system, and graduated from [[Lanier High School (Jackson, Mississippi)|Lanier High School]].<ref name=Genzlinger>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/obituaries/lerone-bennett-jr-historian-of-black-america-dies-at-89.html |title=Lerone Bennett Jr., Historian of Black America, Dies at 89 |last=Genzlinger |first=Neil |date=2018-02-16 |work=The New York Times |access-date=2018-03-01 |language=en-US |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> Bennett attended [[Morehouse College]] in [[Atlanta]], Georgia, where he was classmates with [[Martin Luther King Jr.]] Graduating in 1949, Bennett recalled that this period was integral to his intellectual development. He also joined the [[Kappa Alpha Psi]] fraternity. |

||

===Career=== |

===Career=== |

||

Bennett served as a soldier during the [[Korean War]], and later pursued graduate studies. He was a journalist for the ''[[Atlanta Daily World]]'' from 1949 until 1953. He also worked as city editor for ''[[Jet (magazine)|JET]]'' magazine from 1952 to 1953.<ref name="aar">[http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/lerone-bennett-jr-classical-author "Lerone Bennett Jr. A Classical Author"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141023135947/http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/lerone-bennett-jr-classical-author |date=October 23, 2014 }} |

Bennett served as a soldier during the [[Korean War]], and later pursued graduate studies. He was a journalist for the ''[[Atlanta Daily World]]'' from 1949 until 1953. He also worked as city editor for ''[[Jet (magazine)|JET]]'' magazine from 1952 to 1953.<ref name="aar">[http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/lerone-bennett-jr-classical-author "Lerone Bennett Jr., A Classical Author"], African-American Registry {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141023135947/http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/lerone-bennett-jr-classical-author |date=October 23, 2014 }}.</ref> The magazine had been established in 1945 by [[John H. Johnson]], who founded its parent magazine, ''[[Ebony (magazine)|Ebony]]'', that same year. In 1953, Bennett became associate editor of ''Ebony'' magazine and then executive editor from 1958. The magazine served as his base for the publication of a series of articles on African-American history. Some were collected and published as books. |

||

Bennett wrote a 1954 article "Thomas Jefferson's Negro Grandchildren |

Bennett wrote a 1954 article "Thomas Jefferson's Negro Grandchildren",<ref name="bennett">{{cite magazine|first=Lerone|last=Bennett|title=Thomas Jefferson's Negro Grandchildren|magazine=[[EBONY]]|volume= X |date=November 1954|pages= 78–80}}</ref> about the 20th-century lives of individuals claiming descent from [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]] and his slave [[Sally Hemings]]. It brought black oral history into the public world of journalism and published histories. This [[Jefferson–Hemings controversy|relationship was long denied]] by Jefferson's daughter and two of her children, and mainline historians relied on their account. But new works published in the 1970s and 1990s challenged the conventional story. Since a 1998 [[DNA]] study demonstrated a match between an [[Eston Hemings]] descendant and the Jefferson male line, the historic consensus has shifted (including the position of the [[Thomas Jefferson Foundation]] at [[Monticello]]) to acknowledging that Jefferson likely had a 38-year relationship with Hemings and fathered all six of her children of record, four of whom survived to adulthood.<ref name="Study">[http://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/vi-conclusions "Conclusions"], ''Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings'', Monticello, January 2000. Retrieved March 9, 2011. Quote: "The DNA study, combined with multiple strands of currently available documentary and statistical evidence, indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings, and that he most likely was the father of all six of Sally Hemings's children appearing in Jefferson's records. Those children are Harriet, who died in infancy; Beverly; an unnamed daughter who died in infancy; Harriet; Madison; and Eston."</ref><ref name="Brief">{{cite web|title=Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account|url=http://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/thomas-jefferson-and-sally-hemings-brief-account|work=Monticello|publisher=Thomas Jefferson Foundation|accessdate=November 4, 2011}}</ref> |

||

{{external media| float = right| video2 = [https://www.c-span.org/video/?159690-1/forced-glory Panel discussion on ''Forced Into Glory'', September 24, 2000], [[C-SPAN]]| video1 = [https://www.c-span.org/video/?158187-1/forced-glory ''Booknotes'' interview with Bennett on ''Forced Into Glory'', September 10, 2000], [[C-SPAN]]}} |

{{external media| float = right| video2 = [https://www.c-span.org/video/?159690-1/forced-glory Panel discussion on ''Forced Into Glory'', September 24, 2000], [[C-SPAN]]| video1 = [https://www.c-span.org/video/?158187-1/forced-glory ''Booknotes'' interview with Bennett on ''Forced Into Glory'', September 10, 2000], [[C-SPAN]]}} |

||

Bennett served as a visiting professor of history at [[Northwestern University]].<ref name="Goldsborough">{{Cite news|last=Goldsborough|first=Bob|date=February 16, 2018|title=Lerone Bennett, historian and former executive editor of Ebony magazine, dies|language=en-US|work=Chicago Tribune|url=http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/obituaries/ct-met-lerone-bennett-obituary-20180216-story.html|access-date=2018-03-01}}</ref> He authored several books, including multiple histories of the African-American experience. These include his first work, ''Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America, 1619–1962'' (1962), which discusses the contributions of African Americans in the United States from its earliest years. His 2000 book, ''[[Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream]]'', questions [[Abraham Lincoln]]'s role as the "Great Emancipator". This last work was described by one reviewer as a "flawed mirror", and it was criticized by historians of the Civil War period, such as [[James M. McPherson|James McPherson]] and [[Eric Foner]].<ref>{{cite journal|first=John M. |last=Barr|title=Holding Up a Flawed Mirror to the American Soul: Abraham Lincoln in the Writings of Lerone Bennett Jr.|journal=Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association|number= 35|date=Winter 2014|pages= 43–65}}</ref> Bennett is credited with the phrase: "Image Sees, Image Feels, Image Acts," meaning the images that people see influence how they feel, and ultimately how they act.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} |

|||

A longtime resident of [[Kenwood, Chicago]], Bennett died of natural causes at his home there on 14 February 2018, aged 89.<ref name="Goldsborough" /> |

A longtime resident of [[Kenwood, Chicago]], Bennett died of natural causes at his home there on 14 February 2018, aged 89.<ref name="Goldsborough" /> |

||

==Personal life== |

==Personal life== |

||

A [[Catholic Church|Catholic]], Bennett married Gloria Sylvester (1930–2009) on July 21, 1956, at St. Columbanus Church in Chicago.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Strausberg|first=Chinta|date=2018-02-21|title=Funeral services set for Lerone Bennett, Jr.|url=https://chicagocrusader.com/funeral-services-set-for-lerone-bennett-jr/|access-date=2021-05-08|website=Chicago Crusader|language=en-US}}</ref> They met while working together at ''JET''. The couple had four children: Alma Joy, Constance, Courtney, and Lerone III (1960–2013).<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/atlanta/obituary.aspx?n=lerone-bennett&pid=162622673&fhid=5381 |title=Lerone BENNETT III |

A [[Catholic Church|Catholic]], Bennett married Gloria Sylvester (1930–2009) on July 21, 1956, at St. Columbanus Church in Chicago.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Strausberg|first=Chinta|date=2018-02-21|title=Funeral services set for Lerone Bennett, Jr.|url=https://chicagocrusader.com/funeral-services-set-for-lerone-bennett-jr/|access-date=2021-05-08|website=Chicago Crusader|language=en-US}}</ref> They met while working together at ''JET''. The couple had four children: Alma Joy, Constance, Courtney, and Lerone III (1960–2013).<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/atlanta/obituary.aspx?n=lerone-bennett&pid=162622673&fhid=5381 |title=Lerone BENNETT III Obituary |newspaper= Atlanta Journal-Constitution |date=January 25, 2013 |access-date=2018-03-01}}</ref> |

||

==Legacy and honors== |

==Legacy and honors== |

||

*2003 – [[Carter G. Woodson]] Lifetime Achievement Award from [[Association for the Study of African American Life and History]]<ref>[http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HST/is_1_6/ai_112084296/ |

*2003 – [[Carter G. Woodson]] Lifetime Achievement Award from [[Association for the Study of African American Life and History]]<ref>Dawkins, Wayne, [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HST/is_1_6/ai_112084296/ "Black America's popular historian: Lerone Bennett Jr. almost retired after 50 years at Ebony. Now his next five books, like his first 10 works, will have to be written after hours, too - spotlight"], ''[[Black Issues Book Review]]'', January–February 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2009. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060406083550/http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HST/is_1_6/ai_112084296 |date=April 6, 2006 }}.</ref> |

||

*1978 – Literature Award of the [[American Academy of Arts and Letters]] |

*1978 – Literature Award of the [[American Academy of Arts and Letters]] |

||

*1965 – Patron Saints Award from the Society of Midland Authors |

*1965 – Patron Saints Award from the Society of Midland Authors |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{commons category|Lerone Bennett, Jr.}} |

{{commons category|Lerone Bennett, Jr.}} |

||

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20150318173327/http://www.nathanielturner.com/leronebennettbio.htm Bennett |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20150318173327/http://www.nathanielturner.com/leronebennettbio.htm "Lerone Bennett, Jr. Bio"], ''ChickenBones: A Journal''. |

||

*[http://www.visionaryproject.com/bennettlerone Lerone Bennett Jr.'s oral history video excerpts] at The National Visionary Leadership Project |

*[http://www.visionaryproject.com/bennettlerone Lerone Bennett Jr.'s oral history video excerpts] at The National Visionary Leadership Project |

||

*{{C-SPAN|84824}} |

*{{C-SPAN|84824}} |

||

*[http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/cr2j9 Lerone Bennett Jr. Papers] at [https://rose.library.emory.edu/ Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University] |

*[http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/cr2j9 Lerone Bennett Jr. Papers] at [https://rose.library.emory.edu/ Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University] |

||

*[https://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip_529-3t9d50h089 Discussion panel featuring Lerone Bennett Jr.] at the 22nd annual convention of the [[National Association of Black Journalists]] on [[KUT]]'s "[[In Black America]]" radio program, September 1, 1998, at the [[American Archive of Public Broadcasting]] |

*[https://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip_529-3t9d50h089 Discussion panel featuring Lerone Bennett Jr.] at the 22nd annual convention of the [[National Association of Black Journalists]] on [[KUT]]'s "[[In Black America]]" radio program, September 1, 1998, at the [[American Archive of Public Broadcasting]]. |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

[[Category:1928 births]] |

[[Category:1928 births]] |

||

[[Category:2018 deaths]] |

[[Category:2018 deaths]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century African-American people]] |

||

[[Category:21st-century African-American people]] |

|||

[[Category:African-American Catholics]] |

|||

[[Category:African-American historians]] |

[[Category:African-American historians]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Johnson Publishing Company]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:African-American journalists]] |

[[Category:African-American journalists]] |

||

[[Category:Journalists from Georgia (U.S. state)]] |

|||

[[Category:American Book Award winners]] |

[[Category:American Book Award winners]] |

||

[[Category:Deaths from dementia in Illinois]] |

[[Category:Deaths from dementia in Illinois]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Historians from Mississippi]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Johnson Publishing Company]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Journalists from Georgia (U.S. state)]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Latest revision as of 14:23, 28 April 2024

Lerone Bennett Jr. | |

|---|---|

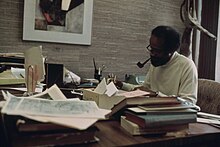

Bennett in his office at Johnson Publishing Company headquarters, 1973. Photo by John H. White. | |

| Born | October 17, 1928 Clarksdale, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | February 14, 2018 (aged 89) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1949–2018 |

| Known for | Before the Mayflower (1962) Forced into Glory (2000) |

| Spouse |

Gloria Sylvester

(m. 1956; died 2009) |

| Children | 4 |

Lerone Bennett Jr. (October 17, 1928 – February 14, 2018) was an African-American scholar, author and social historian who analyzed race relations in the United States. His works included Before the Mayflower (1962) and Forced into Glory (2000), a book about U.S. President Abraham Lincoln.

Born and raised in Mississippi, Bennett graduated from Morehouse College. He served in the Korean War and began a career in journalism at the Atlanta Daily World before being recruited by Johnson Publishing Company to work for JET magazine. Later, Bennett was the long-time executive editor of Ebony magazine. He was associated with the publication for more than 50 years. Bennett also served as a visiting professor of history at Northwestern University.

Biography[edit]

Early life and education[edit]

Bennett was born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, on October 17, 1928, the son of Lerone Bennett Sr. and Alma Reed. When he was young, his family moved to Jackson, Mississippi, the capital. His father worked as a chauffeur and.his mother was a maid but they divorced when he was a child. At twelve he began writing for The Mississippi Enterprise, a Jackson, Mississippi, black owned paper. He recalled once getting in trouble for being distracted from an errand when he happened upon a newspaper to read. He attended segregated schools as a child under the state system, and graduated from Lanier High School.[1] Bennett attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, where he was classmates with Martin Luther King Jr. Graduating in 1949, Bennett recalled that this period was integral to his intellectual development. He also joined the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity.

Career[edit]

Bennett served as a soldier during the Korean War, and later pursued graduate studies. He was a journalist for the Atlanta Daily World from 1949 until 1953. He also worked as city editor for JET magazine from 1952 to 1953.[2] The magazine had been established in 1945 by John H. Johnson, who founded its parent magazine, Ebony, that same year. In 1953, Bennett became associate editor of Ebony magazine and then executive editor from 1958. The magazine served as his base for the publication of a series of articles on African-American history. Some were collected and published as books.

Bennett wrote a 1954 article "Thomas Jefferson's Negro Grandchildren",[3] about the 20th-century lives of individuals claiming descent from Jefferson and his slave Sally Hemings. It brought black oral history into the public world of journalism and published histories. This relationship was long denied by Jefferson's daughter and two of her children, and mainline historians relied on their account. But new works published in the 1970s and 1990s challenged the conventional story. Since a 1998 DNA study demonstrated a match between an Eston Hemings descendant and the Jefferson male line, the historic consensus has shifted (including the position of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello) to acknowledging that Jefferson likely had a 38-year relationship with Hemings and fathered all six of her children of record, four of whom survived to adulthood.[4][5]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Bennett served as a visiting professor of history at Northwestern University.[6] He authored several books, including multiple histories of the African-American experience. These include his first work, Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America, 1619–1962 (1962), which discusses the contributions of African Americans in the United States from its earliest years. His 2000 book, Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream, questions Abraham Lincoln's role as the "Great Emancipator". This last work was described by one reviewer as a "flawed mirror", and it was criticized by historians of the Civil War period, such as James McPherson and Eric Foner.[7] Bennett is credited with the phrase: "Image Sees, Image Feels, Image Acts," meaning the images that people see influence how they feel, and ultimately how they act.[citation needed]

A longtime resident of Kenwood, Chicago, Bennett died of natural causes at his home there on 14 February 2018, aged 89.[6]

Personal life[edit]

A Catholic, Bennett married Gloria Sylvester (1930–2009) on July 21, 1956, at St. Columbanus Church in Chicago.[8] They met while working together at JET. The couple had four children: Alma Joy, Constance, Courtney, and Lerone III (1960–2013).[9]

Legacy and honors[edit]

- 2003 – Carter G. Woodson Lifetime Achievement Award from Association for the Study of African American Life and History[10]

- 1978 – Literature Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1965 – Patron Saints Award from the Society of Midland Authors

- 1963 – Book of the Year Award from Capital Press Club

- 1982 – Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women[11]

- Honorary degrees from Morehouse College, Wilberforce University, Marquette University, Voorhees College, Morgan State University, University of Illinois, Lincoln College, and Dillard University.

Bibliography[edit]

- Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America, 1619–1962 (1962)

- What Manner of Man: A Biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964)

- Confrontation: Black and White (1965)

- Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction 1867–1877 (1967)

- Pioneers In Protest: Black Power U.S.A. (1968)

- The Challenge of Blackness (1972)

- The Shaping of Black America (1975)

- Wade in the Water: Great Moments in Black History (1979)

- Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream (2000), Chicago: Johnson Pub. Co. (review by Eric Foner)

References[edit]

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (February 16, 2018). "Lerone Bennett Jr., Historian of Black America, Dies at 89". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Lerone Bennett Jr., A Classical Author", African-American Registry Archived October 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Bennett, Lerone (November 1954). "Thomas Jefferson's Negro Grandchildren". EBONY. Vol. X. pp. 78–80.

- ^ "Conclusions", Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Monticello, January 2000. Retrieved March 9, 2011. Quote: "The DNA study, combined with multiple strands of currently available documentary and statistical evidence, indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston Hemings, and that he most likely was the father of all six of Sally Hemings's children appearing in Jefferson's records. Those children are Harriet, who died in infancy; Beverly; an unnamed daughter who died in infancy; Harriet; Madison; and Eston."

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account". Monticello. Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Goldsborough, Bob (February 16, 2018). "Lerone Bennett, historian and former executive editor of Ebony magazine, dies". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Barr, John M. (Winter 2014). "Holding Up a Flawed Mirror to the American Soul: Abraham Lincoln in the Writings of Lerone Bennett Jr". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association (35): 43–65.

- ^ Strausberg, Chinta (February 21, 2018). "Funeral services set for Lerone Bennett, Jr". Chicago Crusader. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Lerone BENNETT III Obituary". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. January 25, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Dawkins, Wayne, "Black America's popular historian: Lerone Bennett Jr. almost retired after 50 years at Ebony. Now his next five books, like his first 10 works, will have to be written after hours, too - spotlight", Black Issues Book Review, January–February 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2009. Archived April 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Candace Award Recipients 1982–1990, Page 1". National Coalition of 100 Black Women. Archived from the original on March 14, 2003.

Further reading[edit]

- Barr, John M. "Holding Up a Flawed Mirror to the American Soul: Abraham Lincoln in the Writings of Lerone Bennett Jr." Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 35.1 (2014): 43–65. online

- West, E. James. "Lerone Bennett, Jr.: A Life in Popular Black History." The Black Scholar 47.4 (2017): 3–17.

- West, E. James. Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr.: Popular Black History in Postwar America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020).

External links[edit]

- "Lerone Bennett, Jr. Bio", ChickenBones: A Journal.

- Lerone Bennett Jr.'s oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Lerone Bennett Jr. Papers at Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

- Discussion panel featuring Lerone Bennett Jr. at the 22nd annual convention of the National Association of Black Journalists on KUT's "In Black America" radio program, September 1, 1998, at the American Archive of Public Broadcasting.

- 1928 births

- 2018 deaths

- 20th-century African-American people

- 21st-century African-American people

- African-American Catholics

- African-American historians

- African-American journalists

- American Book Award winners

- Deaths from dementia in Illinois

- Historians from Mississippi

- Johnson Publishing Company

- Journalists from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Journalists from Mississippi

- Morehouse College alumni

- People from Clarksdale, Mississippi

- Writers from Georgia (U.S. state)