Ted Hughes: Difference between revisions

clean up, typepad blogs not reliable sources |

|||

| Line 217: | Line 217: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|2}} |

||

==Bibliography== |

==Bibliography== |

||

Revision as of 21:59, 16 July 2010

- For the Canadian judge, see Ted Hughes (judge).

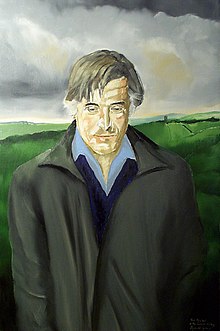

Ted Hughes | |

|---|---|

| 1500*1800 | |

| Occupation | poet |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse | Sylvia Plath (m. 1956-1963) Carol Orchard (m. 1970-1998) |

| Partner | Assia Wevill (?-1969) |

| Children | Frieda Hughes Nicholas Hughes (deceased) Alexandra (deceased) |

Edward James Hughes OM (17 August 1930–28 October 1998) was an English poet and children's writer, known as Ted Hughes. Critics routinely rank him as one of the best poets of his generation.[1] Hughes was British Poet Laureate from 1984 until his death.

Hughes was married to the American poet Sylvia Plath, from 1956 until her death.[2] She committed suicide in 1963 at the age of 30. His part in the relationship became controversial to some feminists and (particularly) American admirers of Plath. Hughes himself never publicly entered the debate, but his last poetic work, Birthday Letters (1998), explored their complex relationship; to some it put him in a significantly better light whereas, to others, it seemed a failed attempt to deflect blame from himself and onto a neurotic father fixation he ascribed to Plath.[3][4]

In 2008, The Times ranked Hughes fourth on their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[5]

On 22 March 2010, it was announced that Hughes would be commemorated with a memorial in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey, to be installed in early 2011.[6]

Early life

Hughes was born on 17 August 1930 at 1 Aspinal Street, in Mytholmroyd, West Yorkshire to William Henry and Edith (née Farrar) Hughes[7] and raised among the local farms in the area. According to Hughes, "My first 6 years shaped everything."[8] When Hughes was seven his family moved to Mexborough, South Yorkshire, where they ran a newsagents and tobacco shop. His brother Gerald was 10 years older and his sister Olwyn, two years older. He attended Mexborough Grammar School, where his teachers encouraged him to write. In 1946 one of his early poems, "Wild West" and a short story were published in the grammar school magazine The Don and Dearne, followed by further poems in 1948.

During the same year Hughes won an Open Exhibition in English at Pembroke College, Cambridge, but chose to do his National Service first.[9] His two years of National Service (1949–51) passed comparatively easily. Hughes was stationed as a ground wireless mechanic in the RAF on an isolated three-man station in east Yorkshire — a time of which he mentions that he had nothing to do but read and reread Shakespeare and watch the grass grow.

Career

Hughes studied English, anthropology and archaeology at Pembroke College.[10] At this time his first published poetry appeared in the journal he started with fellow students, St. Botolph's Review, and at a party to launch the magazine he met Sylvia Plath. He and Plath married at St George the Martyr Holborn on 16 June 1956, four months after they had first met.

Hughes and Plath had two children, Frieda Rebecca and Nicholas Farrar, but separated in the autumn of 1962. He continued to live at Court Green, North Tawton, Devon irregularly with his lover Assia Wevill after Plath's death on 11 February 1963. As Plath's widower, Hughes became the executor of Plath’s personal and literary estates. He oversaw the publication of her manuscripts, including Ariel (1966). He also claimed to have destroyed the final volume of Plath’s journal, detailing their last few months together. In his foreword to The Journals of Sylvia Plath, he defends his actions as a consideration for the couple's young children.

On 25 March 1969, six years after Plath's suicide by asphyxiation from a gas stove, Assia Wevill committed suicide in the same way. Wevill also killed her child, Alexandra Tatiana Elise (nicknamed Shura), the four-year-old daughter of Hughes, born on 3 March 1965.[11]

In August 1970 Hughes married Carol Orchard, a nurse, and they remained together until his death.

Death

He was appointed a member of the Order of Merit by Queen Elizabeth II just before he died. Hughes continued to live at the house in Devon, until his fatal myocardial infarction in a Southwark, London[12] hospital on 28 October 1998, while undergoing treatment for colon cancer.

His funeral was held on 3 November 1998, at North Tawton church, and he was cremated in Exeter. Speaking at the funeral, fellow poet Séamus Heaney, said:

No death outside my immediate family has left me feeling more bereft. No death in my lifetime has hurt poets more. He was a tower of tenderness and strength, a great arch under which the least of poetry's children could enter and feel secure. His creative powers were, as Shakespeare said, still crescent. By his death, the veil of poetry is rent and the walls of learning broken. [13]

A memorial walk was inaugurated in 2005, leading from the Devon village of Belstone to Hughes' memorial stone above the River Taw, on Dartmoor.[14][15]

Nicholas Hughes, the son of Hughes and Plath, committed suicide on 16 March 2009 after battling depression.[16]

Writings

Hughes' earlier poetic work is rooted in nature and, in particular, the innocent savagery of animals, an interest from an early age. He wrote frequently of the mixture of beauty and violence in the natural world. Animals serve as a metaphor for his view on life: animals live out a struggle for the survival of the fittest in the same way that humans strive for ascendancy and success. A classic example is the poem "Hawk Roosting."

His later work is deeply reliant upon myth and the British bardic tradition, heavily inflected with a modernist, and ecological viewpoint. Hughes' first collection, Hawk in the Rain (1957) attracted considerable critical acclaim. In 1959 he won the Galbraith prize which brought $5,000. His most significant work is perhaps Crow (1970), which whilst it has been widely acclaimed also divided critics, combining an apocalyptic, bitter, cynical and surreal view of the universe with what appears to be simple verse. Hughes worked for 10 years on a prose poem, "Gaudete", which he hoped to have made into a film. It tells the story of the vicar of an English village who is carried off by elemental spirits, and replaced in the village by his enantiodromic double, a changeling, fashioned from a log, who nevertheless has the same memories as the original vicar. The double is a force of nature who organises the women of the village into a "love coven" in order that he may father a new messiah. When the male members of the community discover what is going on, they murder him. The epilogue conists of a series of lyrics spoken by the restored priest in praise of a nature goddess, inspired by Robert Graves's white goddess. It was printed in 1977. Hughes was very interested in the relationship between his poetry and the book arts and many of his books were produced by notable presses and in collaborative editions with artists, for instance with Leonard Baskin.[17] In Birthday Letters, his last collection, Hughes broke his silence on Plath, detailing aspects of their life together and his own behaviour at the time. The cover artwork was by their daughter Frieda.

In addition to his own poetry, Hughes wrote a number of translations of European plays, mainly classical ones. HisTales from Ovid (1997) contains a selection of free verse translations from Ovid's Metamorphoses. He also wrote both poetry and prose for children, one of his most successful books being The Iron Man, written to comfort his children after Sylvia Plath's suicide. It later became the basis of Pete Townshend's rock opera of the same name.

Hughes was appointed as Poet Laureate in 1984 following the death of John Betjeman. It was later known that Hughes was second choice for the appointment after Philip Larkin, the preferred nominee, declined, because of ill health and writer's block. Hughes served in this position until his death in 1998. In 1993 his monumental work inspired by Graves' The White Goddess was published. Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being is considered to be a unique work among Shakespeare studies. His definitive 1,333-page Collected Poems (Faber & Faber) appeared in 2003.

Archive

Hughes archival material is held by institutions such as Emory University, Atlanta, Exeter University. The British Library also has a large collection comprising over 220 files containing manuscripts, letters, journals, personal diaries and correspondence. From 2010 the library archive will be accessible through the British Library website.[citation needed]

Selected works

Poetry collections

- 1957 — The Hawk in the Rain

- 1960 — Lupercal

- 1967 — Wodwo

- 1970 — Crow: From the Life and the Songs of the Crow

- 1972 — Selected Poems 1957-1967

- 1975 — Cave Birds

- 1977 — Gaudete

- 1979 — Remains of Elmet (with photographs by Fay Godwin)

- 1979 — Moortown

- 1983 — River

- 1986 — Flowers and Insects

- 1989 — Wolfwatching

- 1992 — Rain-charm for the Duchy

- 1994 — New Selected Poems 1957-1994

- 1997 — Tales from Ovid

- 1998 — Birthday Letters — winner of the 1998 Forward Poetry Prize for best collection, the 1998 T. S. Eliot Prize, and the 1999 British Book of the Year award.

- 2003 — Collected Poems

Translations

- The Oresteia by Aeschylus

- Spring Awakening by Frank Wedekind

- Oedipus by Seneca the Younger

- Blood Wedding by Federico García Lorca

- Phedre by Jean Racine

- Alcestis by Euripides

- Amen by Yehuda Amichai

Anthologies edited by Hughes

- Selected Poems of Emily Dickinson

- Selected Poems of Sylvia Plath

- Selected Verse of Shakespeare

- A Choice of Coleridge's Verse

- The Rattle Bag (edited with Séamus Heaney) ISBN 0-571-11976-X

- The School Bag (edited with Séamus Heaney)

- By Heart: 101 Poems to Remember

- The Mays

Prose

- A Dancer to God

- Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being

- Winter Pollen: Occasional Prose

- Difficulties of a Bridegroom

- Poetry in the Making

Books for children

- Meet my Folks!

- How the Whale Became

- The Earth Owl and Other Moon-People

- Nessie the Mannerless Monster

- Poetry Is ISBN 0-385-03477-6

- The Iron Man

- Coming of the Kings and Other Plays

- Season Songs

- Moon-Whales

- Moon-Bells

- Under the North Star

- Ffangs the Vampire Bat and the Kiss of Truth

- Tales of the Early World

- The Iron Woman

- The Dreamfighter and Other Creation Tales

- Collected Animal Poems: Vols. 1–4

- The Mermaid's Purse

- The Cat and the Cuckoo

Plays

- The House of Aries (radio play), broadcast, 1960.

- The Calm produced in Boston, MA, 1961.

- A Houseful of Women (radio play), broadcast, 1961.

- The Wound (radio play; also see below), broadcast, 1962

- Difficulties of a Bridegroom (radio play), broadcast, 1963.

- Epithalamium produced in London, 1963.

- Dogs (radio play), broadcast, 1964.

- The House of Donkeys (radio play), broadcast, 1965.

- The Head of Gold (radio play), broadcast, 1967.

- The Coming of the Kings and Other Plays (juvenile)

- The Price of a Bride (juvenile; radio play), broadcast, 1966.

- Adapted Seneca's Oedipus (produced in London 1968)

- Orghast produced in Persepolis, Iran, 1971.

- Eat Crow Rainbow Press (London, England), 1971.

- The Iron Man (based on his juvenile book; televised, 1972).

- Orpheus 1973.

Limited editions

- The Burning of the Brothel (Turret Books, 1966)

- Recklings (Turret Books, 1967)

- Scapegoats and Rabies (Poet & Printer, 1967)

- Animal Poems (Richard Gilbertson, 1967)

- A Crow Hymn (Sceptre Press, 1970)

- The Martyrdom of Bishop Farrar (Richard Gilbertson, 1970)

- Crow Wakes (Poet & Printer, 1971)

- Shakespeare's Poem (Lexham Press, 1971)

- Eat Crow (Rainbow Press, 1971)

- Prometheus on His Crag (Rainbow Press, 1973)

- Crow: From the Life and the Songs of the Crow (Illustrated by Leonard Baskin, published by Faber & Faber, 1973)

- Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter (Rainbow Press,1974)

- Cave Birds (Illustrated by Leonard Baskin, published by Scolar Press, 1975)

- Earth-Moon (Illustrated by Ted Hughes, published by Rainbow Press, 1976)

- Eclipse (Sceptre Press, 1976)

- Sunstruck (Sceptre Press, 1977)

- A Solstice (Sceptre Press, 1978)

- Orts (Rainbow Press, 1978)

- Moortown Elegies (Rainbow Press, 1978)

- The Threshold (Illustrated by Ralph Steadman, published by Steam Press, 1979)

- Adam and the Sacred Nine (Rainbow Press, 1979)

- Four Tales Told by an Idiot (Sceptre Press, 1979)

- The Cat and the Cuckoo (Illustrated by R.J. Lloyd, published by Sunstone Press, 1987)

- A Primer of Birds: Poems (Illustrated by Leonard Baskin, published by Gehenna Press, 1989)

- Capriccio (Illustrated by Leonard Baskin, published by Gehenna Press, 1990)

- The Mermaid's Purse (Illustrated by R.J. Lloyd, published by Sunstone Press, 1993)

- Howls and Whispers (Illustrated by Leonard Baskin, published by Gehenna Press, 1998)

Many of Ted Hughes' poems have been published as limited-edition broadsides.[18]

References

- ^ Daily Telegraph, "Philip Hensher reviews Collected Works of Ted Hughes, plus other reviews", April 2004

- ^ Joanny Moulin (2004). Ted Hughes: alternative horizons. p.17. Routledge, 2004

- ^ Middlebrook, D. Her Husband: Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, A Marriage. London, Penguin: 2003.

- ^ "''Ted Hughes: A Talented Murderer'': Guardian journalist Nadeem Azam, writing in 1Lit.com, 2006". 1lit.tripod.com. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ (5 January 2008). The 50 greatest British writers since 1945. The Times. Retrieved on 2010-02-01.

- ^ Poets' Corner memorial for Ted Hughes, BBC News, 22 March 2010

- ^ "Ted Hughes Homepage". ann.skea.com. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Ted Hughes: Timeline". Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ Keith M. Sagar (1981). Ted Hughes p.9. University of Michigan

- ^ "Ted Hughes". www.kirjasto.sci.fi. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ Yehuda Koren and Eilat Negev. "''Written out of history'' Guardian article on Wevill and Hughes 19 October 2006". Guardian. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "Deaths England and Wales 1984-2006". Findmypast.com. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ |title=Centre for Ted Hughes Studies - Ted Hughes timeline Accessdate 2010-04-27

- ^ BBC Devon article - Walking with words on park trail. 28 April 2006

- ^ Ted Hughes Memorial Walk (2008-01-31). "BBC Devon - Ted Hughes memorial". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "Tragic poet Sylvia Plath's son kills himself". CNN. March 23, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ "Richard Price, Ted Hughes and the Book Arts". Hydrohotel.net. 1930-08-17. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Keith Sagar & Stephen Tabor, Ted Hughes: A bibliography 1946-1980 Mansell Publishing, 1983

Bibliography

- The Epic Poise: a celebration of Ted Hughes, edited by Nick Gammage, Faber and Faber, 1999.

- Ted Hughes: the life of a poet, by Elaine Feinstein, W.W. Norton, 2001.

- Bound to Please, by Michael Dirda pp 17–21, W.W. Norton, 2005.

- Ted Hughes: a literary life, by Neil Roberts, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

External links

- British Library - modern British Collections on Ted Hughes accessed 2010-02-22

- British Library - acquisition of archive press release 2008 accessed 2010-02-22

- British Library Hughes cataloguing blog accessed 2010-02-22

- Ted Hughes archive at Emory University accessed 2010-02-22

- Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath collection at University of Victoria, Special Collections accessed 2010-02-22

- Ted Hughes website with bibliography, biographical information, essays etc accessed 2010-02-22

- Ted Hughes resource by Ann Skea accessed 2010-02-22

- Biography of Ted Hughes accessed 2010-02-22

- Ted Hughes resource accessed 2010-02-22

- The Elmet Trust celebrating Ted Hughes accessed 2010-02-22

- essay on Ted Hughes and Schopenhauer: the poetry of the will

- Guardian article Son of poets Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes kills himself 23 March 2009 accessed 2010-02-22

- Guardian article on Wevill and Hughes' relationship 19 October 2006 accessed 2010-02-22

- 1930 births

- 1998 deaths

- Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge

- Cancer deaths in England

- Cardiovascular disease deaths in England

- Deaths from colorectal cancer

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- English astrologers

- English children's writers

- English poets

- English Poets Laureate

- Guardian award winners

- Members of the Order of Merit

- People from Mytholmroyd

- Sylvia Plath