Proclamation of the Irish Republic

| Proclamation of the Republic | |

|---|---|

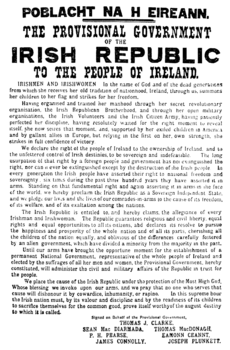

A retouched copy of the original Proclamation | |

| Presented | 24 April 1916 |

| Signatories | 7 members of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic |

| Purpose | To announce separation from the United Kingdom |

The Proclamation of the Republic (Irish: Forógra na Poblachta), also known as the 1916 Proclamation or the Easter Proclamation, was a document issued by the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Rising in Ireland, which began on 24 April 1916.[1][2] In it, the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, writing as the "Provisional Government of the Irish Republic," proclaimed Ireland's independence from the United Kingdom. The reading of the proclamation by Patrick Pearse outside the General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street (now called O'Connell Street), Dublin's main thoroughfare, marked the beginning of the Rising.[3] The proclamation was modelled on a similar independence proclamation issued during the 1803 rebellion by Robert Emmet.[4]

Principles of the proclamation

[edit]Although the Rising failed in military terms, the principles of the Proclamation to varying degrees influenced the thinking of later generations of Irish politicians. The document consisted of a number of assertions:

- the Rising's leaders spoke for Ireland (a claim historically made by Irish insurrectionary movements);

- the Rising marked another wave of attempts to achieve independence through force of arms;

- the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Irish Volunteers, and the Irish Citizen Army were central to the Rising;

- "the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland"

- the form of government was to be a republic;

- a guarantee of "religious and civil liberty, equal rights, and equal opportunities to all its citizens", the first mention of gender equality... Irish women under British law were not allowed to vote;

- a commitment to universal suffrage without distinction of sex, a phenomenon limited at the time to only a handful of countries and which did not yet exist in the UK;

- a promise of "cherishing all the children of the nation equally". Although these words are quoted since the 1990s by children's rights advocates, "children of the nation" refers to all Irish people;[5]

- disputes between nationalists and unionists are attributed to "differences carefully fostered by an alien government", a rejection of what was later dubbed two-nations theory.

The printing and distribution of the text

[edit]The proclamation was printed prior to the Rising on a Summit Wharfedale Stop Cylinder Press in Liberty Hall, Eden Quay (HQ of the Irish Citizen Army). The document had problems with the layout and design because of a shortage of type. It was printed in two-halves, printing first the top, then the bottom on one sheet of paper. The paper was sourced from the Swift Brook Paper Mills in Saggart.[6] The typesetters were Willie O'Brien, Michael Molloy, and Christopher Brady.[7] They lacked a sufficient supply of type in typeface of the same size, and as a result, some parts of the document use an e from a different typeface, which are smaller and do not match.

The language suggested the original copy of the proclamation was signed by the Rising's leaders. However, no evidence is found nor do any contemporary records mention, the existence of an actually signed copy, although if such a copy existed, it could easily be destroyed in the aftermath of the Rising by someone with no appreciation of its historic importance. Molloy says he set the document from a handwritten copy, with signatures on a separate piece of paper which he destroyed by chewing while in prison, but this was disputed by other participants.[8] Molloy also recalled Connolly asked for the document to resemble an auctioneer's notice in general design.[9]

About thirty originals remain, one of which can be viewed in the National Print Museum.[10] Later reproductions are sometimes mis-attributed as originals.[9][11] After British soldiers recaptured Liberty Hall, they found the press with the type of the bottom of the proclamation, and reportedly ran off some copies as souvenirs, leading to a proliferation of these 'half-copies'.[9] James Mosley notes complete originals rapidly became rare in the chaos, and, over a month later, the Dublin police force failed to find any for their files.[9]

The signatories

[edit]The signatories (as their names appeared on the Proclamation):

- Thomas J. Clarke

- Seán Mac Diarmada

- Thomas MacDonagh

- P. H. Pearse

- Éamonn Ceannt

- James Connolly

- Joseph Plunkett

The first name among the signatories is not Pearse but Tom Clarke, a veteran republican. If the arrangement of names were alphabetical, Éamonn Ceannt would appear on top. Clarke's widow maintained it was because the plan was for Clarke, a famed veteran, to become the President of the Provisional Republic. This explanation explains his top position. However, others associated with the Rising dismissed these claims made in her memoirs. Later documents issued by the rebels gave Pearse pride of place, although as 'Commanding in Chief the Forces of the Irish Republic, and President of the Provisional Government,[12] not 'President of the Republic'. Historians continue to speculate whether Clarke was to be a symbolic head of state and Pearse as head of government or Pearse was always to be central but with statements ambiguously describing his title.

All seven signatories of the proclamation were executed by the British military (James Connolly who had been wounded in the fighting was executed sitting down in a chair) in the aftermath of the Rising, being viewed as having committed treason in wartime (i.e. the First World War).[fn 1] British political leaders regarded the executions initially as unwise, later as a catastrophe, with the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and later prime minister David Lloyd George stating that they regretted allowing the British military to treat the matter as a matter of military law in wartime, rather than insisting that the leaders were treated under civilian criminal law. Though initially deeply unsympathetic to the Rising (the leading Irish nationalist newspaper, the Irish Independent called for their execution), Irish public opinion switched and became more sympathetic due to the manner of their treatment and executions.[citation needed] Eventually Asquith's government ordered a halt to the executions and insisted that those not already executed be dealt with through civilian, not military, law. By that stage, all the signatories and a number of others had been executed.

The document today

[edit]

Full copies of the Easter Proclamation are now treated as a revered Irish national icon, and a copy was sold at auction for €390,000 in December 2004.[13] A copy owned (and later signed as a memento) by Rising participant Seán T. O'Kelly was presented by him to the Irish parliament buildings, Leinster House, during his tenure as President of Ireland. It is currently on permanent display in the main foyer. Other copies are on display in the GPO (headquarters of the Rising and the place where the Proclamation was first read), the National Museum of Ireland, the Trinity College Library's Long Room, the GAA Museum in Croke Park, and other museums worldwide. Facsimile copies are sold as souvenirs in Ireland, and copies of the text are often displayed in Irish schools and in Irish pubs throughout the world. The proclamation is read aloud by an Officer of the Irish Defence Forces outside the GPO during the Easter Rising commemorations on Easter Sunday of each year.

Text

[edit]POBLACHT NA hÉIREANN

THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT

OF THE

IRISH REPUBLIC

TO THE PEOPLE OF IRELAND

IRISHMEN AND IRISHWOMEN:

In the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.

Having organised and trained her manhood through her secret revolutionary organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and through her open military organisations, the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army, having patiently perfected her discipline, having resolutely waited for the right moment to reveal itself, she now seizes that moment and supported by her exiled children in America and by gallant allies in Europe, but relying in the first on her own strength, she strikes in full confidence of victory.

We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible. The long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and government has not extinguished the right, nor can it ever be extinguished except by the destruction of the Irish people. In every generation the Irish people have asserted their right to national freedom and sovereignty; six times during the past three hundred years they have asserted it in arms. Standing on that fundamental right and again asserting it in arms in the face of the world, we hereby proclaim the Irish Republic as a Sovereign Independent State, and we pledge our lives and the lives of our comrades in arms to the cause of its freedom, of its welfare, and of its exaltation among the nations.

The Irish Republic is entitled to, and hereby claims, the allegiance of every Irishman and Irishwoman. The Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts, cherishing all the children of the nation equally, and oblivious of the differences carefully fostered by an alien Government, which have divided a minority from the majority in the past.

Until our arms have brought the opportune moment for the establishment of a permanent National Government, representative of the whole people of Ireland and elected by the suffrages of all her men and women, the Provisional Government, hereby constituted, will administer the civil and military affairs of the Republic in trust for the people.

We place the cause of the Irish Republic under the protection of the Most High God, Whose blessing we invoke upon our arms, and we pray that no one who serves that cause will dishonour it by cowardice, inhumanity, or rapine. In this supreme hour the Irish nation must, by its valour and discipline, and by the readiness of its children to sacrifice themselves for the common good, prove itself worthy of the august destiny to which it is called.

- Signed on behalf of the Provisional Government:

- THOMAS J. CLARKE

|

|

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Dublin Gazette, Proclamation of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Wimborne, on 9 May 1916 had proclaimed Dublin under martial law, with the statement that subsequent actions by the Dublin Castle administration would be taken in accordance with that declaration.

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2015) |

- De Paor, Liam (1997). On the Easter Proclamation: And Other Declarations. Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781851823222.

- Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins (ISBN 0-09-174106-8)

- Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera (ISBN 0-09-175030-X)

- Dorothy McCardle, The Irish Republic

- Arthur Mitchell and Padraig Ó Snodaigh, Irish Political Documents: 1916–1949

- John O'Connor, The 1916 Proclamation

- Conor Kostick & Lorcan Collins, The Easter Rising, A Guide to Dublin in 1916 (ISBN 0-86278-638-X)

Citations

[edit]- ^ "CAIN: Proclamation of the Irish Republic, 24 April 1916". cain.ulster.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "BBC - History - 1916 Easter Rising - Insurrection - The Proclamation". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Davidson, Paul. "UCC Library: 1916 Proclamation: Home". libguides.ucc.ie. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Dublin, Trinity College. "The Proclamation – The Spirit of 1916 Captured on a Piece of Paper". www.tcd.ie. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ De Paor 1997, p.74

- ^ "Rewind: Swiftbrook Paper Mills". 9 April 2020.

- ^ Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (1959). Fifty years of Liberty Hall: the golden jubilee of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union 1909–1959. Dublin: Three Candles. p. 69. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "Witness statement WS 716 (Michael J. Molloy)" (PDF). Bureau of Military History. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Mosley, James. "The image of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic 1916". Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Permanent Exhibitions". National Print Museum (Ireland). 2011. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Mosley, James. "The Proclamation of the Irish Republic: notes from Dublin". Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Pamphlet: "The Provisional Government to the Citizens of Dublin on the Momentous occasion of the proclamation of a Sovereign Independent Irish State"". South Dublin Libraries. 1916. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "History under the Hammer". Belfast Telegraph. 8 June 2005.