Clayoquot Sound

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

| Clayoquot Sound | |

|---|---|

| French: Baie Clayoquot | |

| |

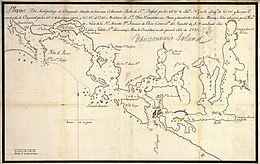

Map of Vancouver Island with inset of Clayoquot Sound region | |

| Location | Vancouver Island, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 49°12′00″N 126°06′00″W / 49.20000°N 126.10000°W |

| Type | Sound |

| Ocean/sea sources | Pacific Ocean |

Clayoquot Sound /ˈklɑːkwɒt/[1][2] is located on the west coast of Vancouver Island in the Canadian province of British Columbia. It is bordered by the Esowista Peninsula to the south, and the Hesquiaht Peninsula to the North. It is a body of water with many inlets and islands. Major inlets include Sydney Inlet, Shelter Inlet, Herbert Inlet, Bedwell Inlet, Lemmens Inlet, and Tofino Inlet. Major islands include Flores Island, Vargas Island, and Meares Island. The name is also used for the larger region of land around the waterbody (essentially its watershed).

Origin of the name

The name Clayoquot is derived from the name of a subgroup of the Nuu-chah-nulth, who lived at Clayoqua, today merged into the multi-group band government known as the Tla-o-qui-aht,[3][4] meaning "different" or "changing".[5][6][7]

History

First Nations have inhabited the area for thousands of years. The oldest dated location within Nuu-cha-nulth territory is 4,200 years (at Yuquot, Nootka Island). However, due to a number of factors, including rising post-glacial sea-level rise, most will date the beginnings of human habitation beyond 9,000 years before present.[8]

In the late 18th century, Clayoquot Sound was explored by various European and American ships, which were mainly involved in the fur trade. In 1791 the complex inner waters were explored and mapped by José María Narváez and Juan Carrasco while their commander, Francisco de Eliza met and befriended Wickaninnish, the chief of the Tla-o-qui-aht peoples.[9][10]

The region's wealth of natural resources was discovered in the 18th century with the arrival of the first European explorers. This wealth attracted growing numbers of foreigners, limiting First Nation access to land, and creating increasing displeasure among the locals. Government support of private company resource extraction allowed for the growth of this industry over time, resulting in the presence of logging companies in the Clayoquot Sound in the 1980s and 1990s.[11]

Logging protests

The differing opinions between these two groups led to the development of Native lobbying organizations and many negotiations regarding policies and general awareness of the conflict. The situation escalated in the late 1980s when MacMillan Bloedel Corporation's permit to log Meares Island was approved.[12]

Opposition to the MacMillan Bloedel Corporation logging in the Clayoquot Sound was expressed in several peaceful protests and blockades of logging roads ranging from 1980-1994. The largest event occurred in the summer of 1993, when over 800 protestors were arrested and many put on trial.[13] Protestors included local residents of the Sound, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and Ahousaht First Nation bands, NDP MP Svend Robinson, and environmentalist groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Clayoquot Sound.[14]

The portrayal of the logging protests and blockades received worldwide mass media attention, creating national support for environmental movements facing British Columbia and fostering strong advocacy for anti-logging campaigns. Media attention was focused around the perceived unfairness of the masses of individuals getting arrested for joining the peaceful protests and blockades. Participants encountered aggression and intimidation from law enforcement, which eventually helped strengthen public support for non-violent protests.[15]

The first significant change in government policies occurred after the 1990 protests. Implementation of this change took place in July 1995, when all 127 unanimous recommendations made by the scientific panel on Clayoquot Sound were accepted by the Forests Minister of British Columbia, Andrew Petter, and the Environment Minister, Elizabeth Cull on behalf of the NDP government.[16] Greenpeace played a significant role in these protests, instigating a boycott of BC forest products in order to apply pressure on the industry. The boycott was called off once the scientific panel's recommendations were accepted by the government, deferring logging until an inventory of pristine areas was completed. The Annual Allowable Cut and clear-cuts in the area were reduced to a maximum of four hectares. In addition, Eco-Based Planning was to occur once biological and cultural inventories were completed.[17]

Salmon farming and related controversy

The sound's ecological features has made it a major site for the farming of salmon, involving floating feedlots consisting of giant fenced pens, and there are roughly twenty such farms currently in operation.[18] A massive die-off of fish, possibly linked to an algal bloom caused by the intensive farming operation, occurred in 2019.[19] The densely packed farms also provide conditions for the rapid spread of disease, and in fact a virus variant found in Norwegian salmon farms has been found in Clayoquot Sound farmed salmon.[20] Environmental advocacy organizations pointed to these events as evidence of the environmental damage associated with this type of fish farming, and in fact the province of British Columbia has begun the process of closing other salmon farming locations on Vancouver Island, e.g., phasing out the practice in the Discovery Islands on Vancouver Island's east side by 2022.[21]

Indigenous peoples and governments

The members of three major First Nations band governments of the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples inhabit the Clayoquot Sound: the Hesquiaht in the North, the Ahousaht in the middle, and the Tla-o-qui-aht in the south, focused on the village of Opitsaht on Meares Island. The village of Tofino lies opposite Opitsaht on the southern promontory of the entrance to the sound.

In 1985 for the first time in British Columbia history the courts froze resource development on crown land surrounding an issue of Aboriginal title claim. This was stimulated by an injunction granted to Chiefs of the Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht first nations halting logging on Meares Island in Clayoquot Sound pending treaty negotiations. These negotiations led to the signing of the Interim Measures Act (IMA) between the provincial government and Nuu-chah-nulth first nations on March 19, 1994 after protests in 1993 pressured the province to come to a resolution. Local land and resource co-management, and economic development strategies are primary enactments made by the IMA.[22]

In recent years the communities surrounding Clayoquot Sound (Tofino, Ucluelet, and Ahousaht) have been developing new sources of income in light of diminished traditional logging jobs. Key areas of focus have been ecotourism and selective logging based on co-management strategies.[23]

Ecology, parks and terrain

The land around Clayoquot Sound includes vast coastal temperate rain forest, rivers, lakes, marine areas and beaches. It includes part of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve and some of Strathcona Provincial Park. The total size of the Clayoquot Sound region, including both land and water, is 350,000 hectares (860,000 acres).[24] More than 200,000 hectares have been part of a multi-year study[25] using Terrestrial Ecosystem Mapping (TEM) to identify areas prone to geologic and geomorphic hazards, in particular, landslides, soil erosion, and sedimentation, as well as identify and characterize terrain conditions associated with these hazards. The region contains the largest area of intact (unlogged) temperate rainforest left on Vancouver Island.[26][4]

Clayoquot Sound is home to wolves, black bears, cougars, grey whales, orcas, porpoises, seals, sea lions, river otters, bald eagles, osprey, marbled murrelets, Pacific loons, Roosevelt elk, martens, and raccoons.

In 2000, Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve[27] was designated as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO.[28] The designation created world recognition of Clayoquot Sound's biological diversity, and a $12M monetary fund to "support research, education and training in the Biosphere region".[29] At the end of July 2006, a new set of Watershed Plans was approved in Clayoquot Sound, opening the door for logging to proceed through 10,000 hectares of the forest, including pristine old-growth valleys.[30][31][32] As of 2007, both logging tenures within Clayoquot Sound are controlled by aboriginal logging companies:[33] Iisaak Forest Resources controls Timber Forest License (TFL) 57 in Clayoquot Sound,[34][35] and MaMook Natural Resources Ltd, in conjunction with Coulson Forest Products, manages TFL54 in Clayoquot Sound.[36][34]

See also

- Kennedy Lake

- Cougar Annie

- Clayoquot Arm Provincial Park

- Clayoquot Plateau Provincial Park

- Great Bear Rainforest

References

- ^ "Clayoquot Arm". BC Geographical Names.

- ^ Kayak Routes of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Edited Peter McGee: "Clayoquot Sound" by Bonny Glambeck and Dan Lewis, pg. 155

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ The Wild Coast: West Coast Vancouver Island, John Kimantis, Whitecap Books, 2005, pg. 259

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ MacMillan, Emergence of the West Coast Culture Type, 1999, pg 105

- ^ McDowell, Jim (1998). José Narváez: The Forgotten Explorer. Spokane, Washington: The Arthur H. Clark Company. pp. 50–60. ISBN 0-87062-265-X.

- ^ Pethick, Derek (1980). The Nootka Connection: Europe and the Northwest Coast 1790-1795. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-88894-279-6.

- ^ Guppy, Walter (1997). Clayoquot Soundings: A History of Clayoquot Sound, 1880s-1980s. Tofino, British Columbia: Grassroots Publication. pp. 7, 55, 66. ISBN 0-9697703-1-6.

- ^ Goetze, Tara C. (2005). "Empowered Co-Management: Towards Power-Sharing and Indigenous Rights in Clayoquot Sound, BC". Anthropologica. 47 (2): 251, 252. JSTOR 25606239.

- ^ Goetze, Tara C. (2005). "Empowered Co-Management: Towards Power-Sharing and Indigenous Rights in Clayoquot Sound, BC". Anthropologica. 47 (2): 252–253. JSTOR 25606239.

- ^ "Clayoquot Land Use Decision, 1993". Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Walter, P. "Adult Learning in New Social Movements: Environmental Protest and the Struggle for the Clayoquot Sound Rainforest." Adult Education Quarterly 57.3 (2007): 248-63.

- ^ Harter, John-Henry (2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Labour / Le Travail. 54: 112. doi:10.2307/25149506. JSTOR 25149506.

- ^ Harter, John-Henry (2004). "Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971-2000". Labour / Le Travail. 54: 113. doi:10.2307/25149506. JSTOR 25149506.

- ^ "Wild Salmon » Friends Of Clayoquot Sound". Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ "Massive salmon farm die-off pollutes British Columbia's Clayoquot Sound". Oceanographic. 2019-11-28. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ Narwhal, The. "Highly contagious virus found in majority of Clayoquot Sound salmon farms: report". The Narwhal. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ "Major setback for BC salmon farming sector". thefishsite.com. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ Holly S. Mabee, D.B. Tindall, George Hoberg, and J.P. Gladu. "Co-management of Forest Lands: The Cases of Clayoquot Sound and Gwaii Haanas." In Aboriginal Peoples and Forest Lands In Canada, edited by Ronald L. Trosper, and Pamela Perreault D.b. Tindall, pp.242-245. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013.

- ^ "Follow-up to Clayoquot Sound." In Falldown Forest Policy in British Columbia, by Scott L. Aycock, Deborah M. Herbert M. Patricia Marchak, pp.127-129. Vancouver: the David Suzuki Foundation and Ecotrust Canada, 1999.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-14. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Aquatic Report Catalogue". A100.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-14. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve. "Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve". Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ^ Grant, Peter. "Clayoquot Sound". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- ^ "Clayoquot Sound". For.gov.bc.ca. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-05-23. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-10-23. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Iisaak.com". Iisaak.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-08-15. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)