St Catherine's Church, Dublin (Church of Ireland)

| St. Catherine's Church, Dublin | |

|---|---|

Thomas Street façade | |

| |

| 53°20′35″N 6°16′52″W / 53.3430°N 6.2812°W | |

| Location | Dublin |

| Country | Ireland |

| Denomination | Church of Ireland |

| Churchmanship | Low Church |

| Website | saintcatherines.ie |

| History | |

| Dedication | St. Catherine |

| Administration | |

| Province | Province of Dublin |

| Diocese | Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough |

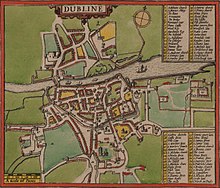

St. Catherine's Church, on Thomas Street, in Dublin, Ireland, was originally built in 1185.[1] It is located on what was once termed the "Slí Mhór" (Irish: Great Way), a key route that ran westwards across Ireland from Dublin. The church was rebuilt in its present form in the 18th century by John Smyth (or Smith).

The church closed in 1966 due to a decrease in the size of the local congregation.[2] The church was de-consecrated the following year, and for a period was used by Dublin Corporation for exhibitions and concerts.[2] After a period of decline, and later of refurbishment, St. Catherine's was re-consecrated and has been the place of worship for the Anglican "CORE" church (City Outreach for Renewal and Evangelism) since then.

History

Parish history

In 1177, the parish of St. James is mentioned as part of the Augustinian abbey of St. Thomas (from which Thomas Street got its name), and the church of St. Catherine was a chapel-of-ease to the abbey. By the end of the 13th century, the western suburbs had so increased in population that a separate parish was deemed necessary. This was provided for by splitting the parish of St. James and setting up an independent parish for St. Catherine's.[3]

Both parishes were still subservient to the Abbey of St. Thomas, but in 1539 the abbey was dissolved with all the monasteries by Henry VIII. In the surrender made by Henry Duffe, last Abbot, were included "the Churches of St. Catherine and St. James near Dublin". Both churches, now independent, had new curates appointed by the crown: Sir John Brace to St. Catherine's (which was shortly taken over by Peter Ledwich (or Ledwidge)) and Sir John Butler to St. James. Over the following hundred years, both churches passed over to the reformed church, while Roman Catholic priests led a precarious existence tending to the larger part of the population, which remained faithful to the old religion.[3]

The parish of St. Catherine appears to have been the only viable one in the area at that time — Roman Catholics eventually got the use of a chapel in Dirty Lane (now Bridgefoot Street) towards the end of the 17th century. Later, another St. Catherine's was founded in Meath Street to cater for the Catholic population.[3]

The two Church of Ireland parishes were separated in 1710.[4]

Building history

The building that stands now was originally built between 1760 and 1769 to the designs of the architect John Smyth[2] (who was also responsible for the interior of St Werburgh's Church, among other works in Dublin at the time).[5]

In 1803 the church was the site of Robert Emmet's execution - and a plaque commemorating this remains today.[6]

Into the 20th century, the Protestant population of the Liberties area of the city declined, and the church closed in September 1966. It was de-consecrated the following year.[2]

St. Catherine's was transferred for a number of years to Dublin Corporation, and was used for exhibitions and concerts - hosting artists such as Christy Moore and The Chieftains.[2] It fell disused in the 1980s however, and the interior was vandalised.[7]

In 1990 Dublin Corporation offered the church for sale as part of an inner city development plan. An Anglican group (City Outreach for Renewal and Evangelism - CORE) took on the refurbishment of the church in 1993, and the interior was largely restored by the end of 1998. In early November 1998 St. Catherine's was reconsecrated and has been an active place of worship since then.[2]

Church architecture

Historian Maurice Craig wrote that St. Catherine's has "the finest façade of any church in Dublin".[8][9] Its façade is built of mountain granite and has in the centre four Doric semi-columns supporting a pediment, and at the extremities coupled pilasters.[7] Originally a spire was intended, but this was not completed due to lack of funds.[4]

Internally, St. Catherine's is a galleried church (a type common in Dublin from the late 17th century)[7] Architects Curdy and Mitchell restored the church in 1877 and during the following decade an interior reordering was undertaken by architect James Franklin Fuller, during which the old box pews were replaced with open ones.

The crypt contains the remains of several Earls of Meath.[7] Christopher Plunkett, 2nd Earl of Fingall, fatally wounded at the Battle of Rathmines, was buried in St Catherine's in August 1649.

Cemetery

The churchyard and cemetery lie to the rear of St. Catherine's. Originally dating to 1552, burials ceased in 1894. The cemetery is now a small public park.[10] There is a plot which was provided by the Protestant Orphan Society for the burial of orphans, in the churchyard. There is a memorial to those took part in the 1803 Rising, and where hanged, some were hanged on Thomas Street.[11]

Clergy

Clergy who have served in St. Catherines have included rectors Rev. James Whitelaw, Rev. John David Hastings, Rev. John Day Hurst[11] and Rev Robert Vance.[citation needed] Rev. Eoghan Heaslip was appointed minister in 2017.[12]

Notable parishioners

- James Whitelaw (1749-1813), historian and statistician, was clergyman in this parish when he died of a fever contracted while visiting afflicted parishioners.[13]

- William Mylne (1734–1790), architect and engineer, who was responsible for the waterworks of Dublin, commemorated by a plaque in the church.[14]

Further reading

- Crawford, Rev. John (1996). St. Catherine's Parish, Dublin, 1840-1900: A Portrait of a Church of Ireland Community. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2593-3.

References

- ^ Gilbert, John (1854). A History of the City of Dublin. Oxford: Oxford University.

- ^ a b c d e f "About us - History". corechurch.ie. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Donnelly, Nicholas (Bishop of Canea). "Part IX - Parishes of St. James & St. Catherine". Short Histories of Dublin Parishes. Catholic Truth Society of Ireland.

- ^ a b G. N. Wright. "An Historical Guide to the City of Dublin". Online book. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "1760 – Provost's House, Trinity College Dublin". Architecture of Dublin City. Archiseek.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Dublin Images - Plaque". robertemmet.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d "St. Catherine's". Database of Irish excavation reports. Excavations.ie. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 7 August 2011 suggested (help) - ^ Craig, Maurice (1969). Dublin: 1660-1860. Dublin: Allen Figgis.

- ^ "Restoring faith in St Catherine's". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 14 September 2000. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "St. Catherine's Park". dublincity.ie. Dublin City Council. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014.

- ^ a b Sean Murphy, ed. (1987). Memorial Inscriptions from St. Catherines Church and Graveyard (PDF). Dublin: Divelina Publications.

- ^ "The Revd Eoghan Heaslip Appointed Minister in Charge of St Catherine's". dublin.anglican.org. United Dioceses of Dublin & Glendalough. 17 January 2017.

- ^ Boylan, Henry (1998). A Dictionary of Irish Biography, 3rd Edition. Dublin: Gill and MacMillan. p. 444. ISBN 0-7171-2945-4.

- ^ Ward, Robert (2007). The Man Who Buried Nelson: The Surprising Life of Robert Mylne. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3922-8.