Nika riots

| Nika riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

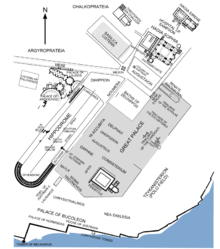

Site of the Hippodrome of Constantinople in Istanbul | |||

| Date | 532 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | See Causes | ||

| Goals | Overthrow Justinian | ||

| Methods | Widespread rioting, property damage, murder | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 30,000 rioters killed[1] | ||

The Nika riots (Template:Lang-el Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They were the most violent riots in the city's history, with nearly half of Constantinople being burned or destroyed and tens of thousands of people killed.

Background

The ancient Roman and Byzantine empires had well-developed associations, known as demes,[2] which supported the different factions (or teams) under which competitors in certain sporting events took part; this was particularly true of chariot racing. There were initially four major factional teams of chariot racing, differentiated by the colour of the uniform in which they competed; the colours were also worn by their supporters. These were the Blues (Veneti), the Greens (Prasini), the Reds (Russati), and the Whites (Albati),[3] although by the Byzantine era the only teams with any influence were the Blues and Greens. Emperor Justinian I was a supporter of the Blues.

The team associations had become a focus for various social and political issues for which the general Byzantine population lacked other forms of outlet.[4] They combined aspects of street gangs and political parties, taking positions on current issues, notably theological problems or claimants to the throne. They frequently tried to affect the policy of the emperors by shouting political demands between races. The imperial forces and guards in the city could not keep order without the cooperation of the circus factions which were in turn backed by the aristocratic families of the city; these included some families who believed they had a more rightful claim to the throne than Justinian.[citation needed]

In 531 some members of the Blues and Greens had been arrested for murder in connection with deaths that occurred during rioting after a recent chariot race.[5] Relatively limited riots were not unknown at chariot races, similar to the football hooliganism that occasionally erupts after association football matches in modern times. The murderers were to be executed, and most of them were.[6] But on January 10, 532, two of them, a Blue and a Green, escaped and were taking refuge in the sanctuary of a church surrounded by an angry mob.

Justinian was nervous: he was in the midst of negotiating with the Persians over peace in the east at the end of the Iberian War and now he faced a potential crisis in his city. Facing this, he declared that a chariot race would be held on January 13 and commuted the sentences to imprisonment. The Blues and the Greens responded by demanding that the two men be pardoned entirely.[citation needed]

Causes

Justinian and two of his leading officials, John the Cappadocian and Tribonian, were extremely unpopular because of the high taxes they levied,[7] the corruption of the latter two[7] and John's cruelty against debtors.[7][8] John and Justinian had also reduced spending on the civil service and combated the corruption of the civil service.[8] The many nobles who had lost their power and fortune when removed from the smaller, less corrupt civil service joined the ranks of the Greens.[8] Justinian was also reducing the power of both teams, the Greens seeing this as further imperial oppression akin to the reforms in the civil service, while the Blues felt betrayed.[8] The Roman legal code had a popular image as the biggest distinguishing feature of the civilized Romans as compared to "barbarians" (Template:Lang-la).[9] The law code was also religiously important as the Romans were believed to be "chosen by God", it being a symbol of justice.[9] As such it brought legitimacy with it if an emperor successfully made significant legal reforms but if this process bogged down it showed divine anger.[9] What had taken nine years for the Theodosian code took Justinian just thirteen months.[9]

Just before the Nika riots of January 532, however, the pace of reforms had slowed to a crawl.[9] At the same time Justinian was fighting an unsuccessful war against the Persians; while Byzantine victories at Dara (spring of 530) and Satala (summer of 530) had fostered his legitimacy for a short while, the defeat at Calinicum (531) and negative strategic situation damaged the emperor's reputation.[9] On top of that the legal reforms were unpopular with the aristocracy from the start, as they made it impossible to use obscure laws and jurisprudence to avoid unfavorable verdicts, further angering the aristocracy.[9] On top of this both Justinian and his wife Theodora were of low birth - late Roman and Byzantine society was not as class driven as the feudal-dominated society of the west.[9] The Greens were a Monophysite group and represented the interest of the moneyed non-landowners, Justinian being neither of those.[10] When Justinian refused to pardon the two arrested rioters there was already a deep-seated resentment among the general populace as well as among the aristocracy.

Riots

On January 13, 532, a tense and angry populace arrived at the Hippodrome for the races.[citation needed] The Hippodrome was next to the palace complex, and thus Justinian could watch from the safety of his box in the palace and preside over the races. From the start, the crowd had been hurling insults at Justinian. By the end of the day, at race 22, the partisan chants had changed from "Blue" or "Green" to a unified Nίκα ("Nika", meaning "Win!" "Victory!" or "Conquer!"), and the crowds broke out and began to assault the palace. For the next five days, the palace was under siege.[citation needed] The fires that started during the tumult resulted in the destruction of much of the city, including the city's foremost church, the Hagia Sophia (which Justinian would later rebuild).

Some of the senators saw this as an opportunity to overthrow Justinian, as they were opposed to his new taxes and his lack of support for the nobility.[citation needed] The rioters, now armed and probably controlled by their allies in the Senate, also demanded that Justinian dismiss the prefect John the Cappadocian and the quaestor Tribonian. They then declared a new emperor, Hypatius, who was a nephew of former Emperor Anastasius I.[citation needed]

Justinian, in despair, considered fleeing, but his wife Theodora is said to have dissuaded him, saying, "Those who have worn the crown should never survive its loss. Never will I see the day when I am not saluted as empress."[11] She is also credited with adding, "[W]ho is born into the light of day must sooner or later die; and how could an Emperor ever allow himself to be a fugitive."[12] Although an escape route across the sea lay open for the emperor, Theodora insisted that she would stay in the city, quoting an ancient saying, "Royalty is a fine burial shroud," or perhaps, "[the royal color] Purple makes a fine winding sheet."[13]

As Justinian rallied himself, he created a plan that involved Narses, a popular eunuch, as well as the generals Belisarius and Mundus. Carrying a bag of gold given to him by Justinian, the slightly built eunuch entered the Hippodrome alone and unarmed against a murderous mob that had already killed hundreds. Narses went directly to the Blues' section, where he approached the important Blues and reminded them that Emperor Justinian supported them over the Greens. He also reminded them that Hypatius, the man they crowned, was a Green. Then, he distributed the gold. The Blue leaders spoke quietly with each other and then they spoke to their followers. Then, in the middle of Hypatius' coronation, the Blues stormed out of the Hippodrome. The Greens sat, stunned. Then, Imperial troops led by Belisarius and Mundus stormed into the Hippodrome, killing any remaining rebels indiscriminately be they Blues or Greens.[12]

About thirty thousand rioters were reportedly killed.[14] Justinian also had Hypatius executed and exiled the senators who had supported the riot. He then rebuilt Constantinople and the Hagia Sophia and was free to establish his rule.

See also

References

- ^ This is the number given by Procopius, Wars (Internet Medieval Sourcebook Archived 2006-02-12 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Joseph Henry Dahmus (1968). The Middle Ages: A Popular History. Doubleday. p. 86.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1867). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Bell & Daldy. p. 301.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Hugh Chisholm; James Louis Garvin (1926). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature & General Information. Encyclopædia Britannica Company, Limited. p. 121.

- ^ "CLIO History Journal - Justinian and the nike riots". Cliojournal.wikispaces.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-19. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1999). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc. p. 64. ISBN 0-679-77269-3.

- ^ a b c Charles River Editors (2014-11-11). The Dark Ages 476-918 these taxes were levied against the rich.A.JUSTINIAN THE GREAT: THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF THE BYZANTINE EMPEROR. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781503190375.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d Hughes, Ian (Historian) (2009). Belisarius : the last Roman general. Yardley, Pa.: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-59416-085-1. OCLC 294885267.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Heather, P. J. (Peter J.) (2018). Rome resurgent : war and empire in the age of Justinian. New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-936274-5. OCLC 1007044617.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^

Charles River Editors (2014-11-11). JUSTINIAN THE GREAT: THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF THE BYZANTINE EMPEROR. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781503190375.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Diehl, Charles. Theodora, Empress of Byzantium (1972). Frederick Ungar Publishing (translated by S. R. Rosenbaum from the original French Theodora, Imperatice de Byzance), p.87.

- ^ a b Norwich, John Julius (1999). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc. p. 64. ISBN 0-679-77269-3.

- ^ Procopius, Wars 1.24.32–37. For the possibility of Theodora's stirring remarks being an invention by Procopius (otherwise an unflattering chronicler of Theodora's life), see John Moorhead, Justinian (London/NY 1994), pp. 46–47, with a reference to J. Evans, "The 'Nika' rebellion and the empress Theodora", in: Byzantion 54 (1984), pp. 380–382.

- ^ This is the number given by Procopius, Wars (Internet Medieval Sourcebook Archived 2006-02-12 at the Wayback Machine.)

Sources

- Diehl, Charles (1972). Theodora, Empress of Byzantium. Frederick Ungar Publishing, Inc. Popular account based on the author's extensive scholarly research.

- Weir, William. 50 Battles That Changed the World: The Conflicts That Most Influenced the Course of History. Savage, Md: Barnes and Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-6609-6.

External links

- Procopius, "Justinian Suppresses the Nika Revolt, 532", from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- J. B. Bury, "The Nika Revolt", chapter XV part 5 from History of the Later Roman Empire (1923).

- James Grout: "The Nika Riot", part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Samuel Vancea: "Justinian and the Nike Riots", published in Clio History Journal