Bali tiger

| Bali tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

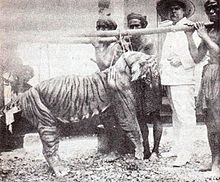

| A Bali tiger killed in 1920s | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †P. t. sondaica

|

| Trinomial name | |

| †Panthera tigris sondaica (Temminck, 1844)

| |

| |

| Former range of the Bali tiger | |

| Synonyms | |

|

P. t. balica (Schwarz, 1912) | |

The Bali tiger was a population of Panthera tigris sondaica, which lived in the Indonesian island of Bali.[2] This population has been extinct since the 1950s.[1]

It was formerly regarded as a distinct tiger subspecies, under the scientific name Panthera tigris balica, which had been assessed as extinct on the IUCN Red List in 2008.[1] In 2017, felid taxonomy was revised and this subspecies subordinated to P. t. sondaica, which also includes the still surviving Sumatran tiger.[2]

Results of mitochondrial DNA analysis of 23 tiger samples from museum collections indicate that tigers colonized the Sunda Islands throughout the last glacial period 11,000–12,000 years ago.[3] In Bali, the last tigers were recorded in the late 1930s. A few individuals likely survived into the 1940s and possibly 1950s. This population was hunted to extirpation and its natural habitat converted for human use.[4]

Balinese names for the tiger are harimau Bali and samong.[5]

Taxonomic history

In 1912, the German zoologist Ernst Schwarz described a skin and a skull of an adult female tiger in the Senckenberg Museum collection, that had originated in Bali. He named it Felis tigris balica and argued that it is distinct from the Javan tiger by its brighter fur colour and smaller skull with narrower zygomatic arches.[6] In 1969, the distinctiveness of the Bali tiger was questioned, since morphological analysis of several tiger skulls from Bali revealed that size variation is similar to Javan tiger skulls. Hue and striping pattern of fur neither differs significantly.[7] A comparison of mitochondrial DNA sequences from 23 museum specimens of Bali and Javan tigers with other living tiger subspecies revealed a close genetic resemblance of the tigers in the Sunda Islands. They form a monophyletic group distinct and equidistant from tigers in mainland Asia.[8]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy, and now recognizes the extinct Bali and Javan tiger populations, as well as the Sumatran tiger population as P. t. sondaica.[2]

Characteristics

The Bali tiger was described as the smallest tiger in the Sunda islands.[6] In the 20th century, only seven skins and skulls of tigers from Bali were known to be preserved in museum collections. The common feature of these skulls is the narrow occipital plane, which is analogous with the shape of tiger skulls from Java.[9] Skins of males measured between the pegs are 220 to 230 cm (87 to 91 in) long from head to end of tail; those of females 190 to 210 cm (75 to 83 in). The weight of males ranged from 90 to 100 kg (200 to 220 lb), and of females from 65 to 80 kg (143 to 176 lb).[10]

Habitat and ecology

Most of the known Bali tiger zoological specimens originated in western Bali, where mangrove forests, dunes and savannah vegetation existed. The main prey of the Bali tiger was likely Javan rusa.[11]

Extirpation

At the end of the 19th century, palm plantations and irrigated rice fields were established foremost on Bali's rich volcanic northern slopes and the alluvial strip around the island. Tiger hunting started after the Dutch gained control over Bali.[11] During the Dutch colonial period, hunting trips were conducted by European sportsmen coming from Java, who had a romantic but disastrous Victorian hunting mentality and were equipped with high-powered rifles. The preferred method of hunting tigers was to catch them with a large, heavy steel foot trap hidden under bait, a goat or a muntjac, and then shoot them at close range. Surabayan gunmaker E. Munaut is confirmed to have killed over 20 tigers in only a few years.[12] In 1941, the first game reserve, today's West Bali National Park, was established in western Bali, but too late to save Bali's tiger population from extinction. It was probably eliminated by the end of World War II. A few tigers may have survived until the 1950s, but no specimen reached museum collections after the war.[11]

A few tiger skulls, skins and bones are preserved in museums. The British Museum in London has the largest collection, with two skins and three skulls; others include the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt, the Naturkunde Museum in Stuttgart, the Naturalis museum in Leiden and the Zoological Museum of Bogor, Indonesia, which owns the remnants of the last known Bali tiger. In 1997, a skull emerged in the old collection of the Hungarian Natural History Museum and was scientifically studied and properly documented.[13]

Cultural significance

The tiger had a well-defined position in Balinese folkloric beliefs and magic. It is mentioned in folk tales and depicted in traditional arts, as in the Kamasan paintings of the Klungkung kingdom. The Balinese considered the ground powder of tiger whiskers to be a potent and undetectable poison for one's foe. A Balinese baby was given a protective amulet necklace with black coral and "a tiger's tooth or a piece of tiger bone".[14] The traditional Balinese Barong dance preserves a figure with the mask of a tiger called Barong Macan.[15]

Balinese people are fond of wearing tiger parts as jewelry for status or spiritual reasons, such as power and protection. Necklaces of teeth and claws or male rings cabochoned with polished tiger tooth ivory still exist in everyday use. Since the tiger has disappeared on both Bali and neighboring Java, old parts have been recycled, or leopard and sun bear body parts have been used instead.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y. & Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66–68.

- ^ Xue, H.R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Driscoll, C.A.; Han, Y.; Bar-Gal, G.K.; Zhuang, Y.; Mazak, J.H.; Macdonald, D.W.; O’Brien, S.J.; Luo, S.J. (2015). "Genetic ancestry of the extinct Javan and Bali tigers". Journal of Heredity. 106 (3): 247–257. doi:10.1093/jhered/esv002. PMC 4406268. PMID 25754539.

- ^ Seidensticker, J. (1987). "Bearing witness: observations on the extinction of Panthera tigris balica and Panthera tigris sondaica". In Tilson, R. L.; Seal, U. S. (eds.). Tigers of the world: the biology, biopolitics, management, and conservation of an endangered species. New Jersey: Noyes Publications. pp. 1–8. ISBN 9780815511335.

- ^ Crawfurd, J. (1820). History of The Indian Archipelago, Volume II. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable & Co.

- ^ a b Schwarz, E. (1912). "Notes on Malay tigers, with description of a new form from Bali". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Series 8 Volume 10 (57): 324–326. doi:10.1080/00222931208693243.

- ^ Hemmer, H. (1969). "Zur Stellung des Tigers (Panthera tigris) der Insel Bali". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 34: 216–223.

- ^ Xue, H.R. (2015). "Genetic Ancestry of the extinct Javan and Bali Tigers". Journal of Hereditary. 106 (3): 247–257. doi:10.1093/jhered/esv002. PMID 25754539.

- ^ "Skin and Skull of the Bali Tiger, and a list of preserved specimens of Panthera tigris balica (Schwarz, 1912)". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde – International Journal of Mammalian Biology 43 (2): 108–113. 1978.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 152 (152): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004. JSTOR 3504004.

- ^ a b c Seidensticker, J. (1986). "Large carnivores and the consequences of habitat insularization: ecology and conservation of tigers in Indonesia and Bangladesh". In S. D. Miller; D. D. Everett (eds.). Cats of the World: biology, conservation, and management. Washington DC: National Wildlife Federation. pp. 1–41.

- ^ Vojnich, G. (1913). A Kelet-Indiai Szigetcsoporton [in the East Indian Archipelago]. Budapest: Singer és Wolfner.

- ^ Buzas, B. and Farkas, B. (1997). An additional skull of the Bali tiger, Panthera tigris balica (Schwarz) in the Hungarian Natural History Museum. Miscellanea Zoologica Hungarica Volume 11: 101–105.

- ^ Covarrubias, M. (1937). Island Of Bali. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc. p. 105.

- ^ Bandem, I. M. (1976). "Barong Dance". The World of Music. 1 (3): 45–52. JSTOR 43563555.

External links

- "Tiger Bali tiger (P. t. balica)". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Death of the Bali Tiger". Save The Tiger Fund. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11.