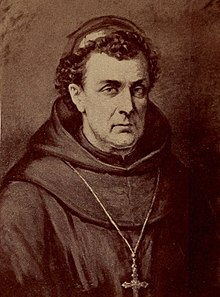

Michael Francis Egan

Michael Francis Egan | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Philadelphia | |

| |

| Province | Baltimore |

| Diocese | Philadelphia |

| Appointed | April 8, 1808 |

| Installed | October 28, 1810 |

| Term ended | July 22, 1814 |

| Predecessor | New diocese |

| Successor | Henry Conwell |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1785 or 1786 |

| Consecration | October 28, 1810 by John Carroll |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 29, 1761 Ireland |

| Died | July 22, 1814 (aged 52) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

Michael Francis Egan OFM (September 29, 1761 – July 22, 1814) was an Irish, later American, prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He was born in Ireland in 1761, and joined the Franciscan Order at a young age. He served as a priest in Rome, Ireland, and Pennsylvania and became known as a gifted preacher. In 1808, Egan was appointed the first Bishop of Philadelphia, and held that position until his death in 1814.[1] Egan's tenure as bishop saw the construction of new churches and the expansion of the Catholic Church membership in his diocese, but much of his time was consumed by disputes with the lay trustees of his pro-cathedral, St. Mary's Church in Philadelphia. He died in Philadelphia, probably of tuberculosis, in 1814.

Early life and priesthood

Michael Francis Egan was born in Ireland on September 29, 1761.[2] The exact location of his birth is disputed. Early biographers believed Egan was possibly born in Galway;[3] more recent scholarship suggests it was Limerick.[1][4] He joined the Order of Friars Minor (commonly known as the Franciscans) and studied at the Old University of Leuven and Charles University in Prague.[1] Egan received minor orders, subdiaconate, and diaconate at Mechelen, in modern-day Belgium.[5] He was ordained a priest, probably in Prague, in 1785 or 1786.[1][2] While studying on the continent, Egan became fluent in German.[5]

Egan advanced rapidly to positions of responsibility in the Franciscan order.[6] He was appointed custos ("guardian") of the province of Munster in Ireland in March 1787.[7] Later that year, he was also appointed custos of the Pontifical College at Sant’Isidoro a Capo le Case, the home of Irish Franciscans in Rome.[7] Egan remained there until 1790, when he returned to Ireland and was appointed custos of Ennis. He remained in Ireland until 1787 or 1788, when he may have made a visit to the United States.[7] After several more years as a missionary in Ireland, Egan came (or returned) to the United States in 1802.[6]

Priest in Pennsylvania

Accepting an invitation from the Catholics near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Egan arrived in the United States in January 1802 to serve as assistant pastor to Louis de Barth at Conewago Chapel in Adams County.[8] When the state legislature sat in Lancaster that year, word of Egan's preaching abilities traveled back to Philadelphia, and soon the parishioners of that city's St. Mary's Church petitioned Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore to send Egan to them. (At that time, the Bishop of Baltimore had jurisdiction over the entire Catholic Church in the United States.)[9]

In 1803, Egan became one of the pastors of St. Mary's Church at Philadelphia.[9] The move coincided with a yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia. Though less virulent than Philadelphia's famous 1793 outbreak of the disease, there were nonetheless many deaths, and Egan presided over many funerals that year—St. Mary's had 77 interments between June and November 1803.[10] In 1804, Egan received permission to establish a province of Franciscans in the United States for the first time, independent of the Irish Franciscans who were then supervising the American mission.[11][12] Two years later, a parishioner willed Egan some land along the Yellow Creek in Indiana County, for the establishment of a Franciscan church.[12] Due to the order's vows of poverty, Egan asked Carroll to hold the land in his name.[13] Egan's dream was never realized, as he was unable to attract Franciscans from Europe to establish the planned church.[14]

Egan and the trustees of St. Mary's established a singing school in 1804, with the goal of improving the quality of the choir there.[15] The following year was consumed by another yellow fever outbreak, and Egan joined John Rossiter, the pastor of another of Philadelphia's four Catholic churches, St. Joseph's, in ministering to the sick.[16] In 1806, they worked with the parishioners of a third church, Holy Trinity, to found an orphanage, as the problem of orphaned children had been made worse by the yellow fever deaths.[17]

Bishop of Philadelphia

Ordination

The Catholic population in the United States was growing, and Bishop John Carroll had for some time wished for his vast diocese to be divided into more manageable territories.[18] On April 8, 1808, Pope Pius VII granted Carroll's request, erecting four new sees in the United States and elevating Baltimore to an archdiocese. Among the new sees was the Diocese of Philadelphia, which included the states of Pennsylvania and Delaware as well as the western and southern parts of New Jersey.[18] Even before the diocese was created, Carroll had determined to recommend Egan for the post, writing to Rome that Egan "was truly pious, learned, religious, remarkable for his great humility, but deficient, perhaps, in firmness and without great experience in the direction of affairs".[19]

As a result of disruptions caused by the Napoleonic Wars, the papal bull nominating Egan did not reach the United States until 1810.[6] When it arrived, Egan traveled to St. Peter's Pro-cathedral in Baltimore, where he was ordained bishop by Carroll, assisted by Benedict Joseph Flaget and Jean-Louis de Cheverus, who had been appointed to bishoprics but had not yet been consecrated.[a][2] Egan chose St. Mary's to serve as his pro-cathedral in Philadelphia.[1] Even before Egan's installation, Philadelphia Catholics began to raise funds to expand the church in accordance with its new prominence in the diocese.[20] After their ordinations, the new bishops planned a council of the American church leadership for the near future; in fact, they did not meet until 1829, long after Egan's death.[14]

Trusteeism dispute

Egan's elevation to the episcopate worsened an existing conflict in the American church: the dispute over trusteeism. In Europe, the Church owned property and directly controlled its parishes through the clergy. In the United States, however, early Catholic churches were typically founded by laymen who purchased the property and erected the church buildings. The laypeople accordingly demanded some control over the administration of the parish, even after the arrival of clergy from Europe who, like Egan, held the traditional view of parish organization.[21] The dispute also had nationalist elements to it, as the heavily German parish of Holy Trinity resented the imposition of an Irish bishop instead of one of their own.[22] When Holy Trinity's pastor left for a new assignment in Maryland in 1811, the trustees there were perturbed at Egan's temporary appointment of an Irish priest, Patrick Kenny, to lead the parish, until a German priest could be found (a German priest, Francis Roloff, was assigned the following year).[23][24]

Egan's own research into the issue showed that the trustees had conveyed St. Mary's Church to the previous pastor, Robert Harding, and then to his heirs, but the trustees did not consider that property transfer to have extinguished their role in the church's leadership.[25] By 1811, Egan's worsening health caused him to accept the assistance of two priests at St. Mary's, James Harold and his nephew, William Vincent Harold.[25] Egan and the trustees became further embroiled in a dispute about clerical salaries, a situation possibly made worse by the decline in shipping income in the port city caused by the outbreak of the War of 1812.[26] Egan also came to believe the Harolds were making the situation worse by taking pro-clergy positions that were more extreme than Egan's own and by the younger Harold's scheming to be named Egan's coadjutor bishop.[27] He appealed to the trustees for compromise, and offered to bring his cousin (also a priest) over from Ireland to replace the elder Harold.[27] By 1813, Egan and the trustees had reconciled and together resolved to remove the Harolds, who agreed to resign later that year and relocate to England.[28]

Death and burial

Although the main complaints between bishop and trustees were resolved, some salary disputes lingered into 1813.[29] The conditions at St. Mary's worsened in 1814 with the election of new trustees who were more in conflict with Egan than the previous ones.[30] Elsewhere in the diocese, Egan was more successful. In about 1811, he made his most extensive visitation of his diocese, travelling as far west as Pittsburgh after stopping in Lancaster and Conewago.[31] He continued to raise funds for the Catholic orphanage and opened a new parish, Sacred Heart, in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1813, bringing the total number of churches in the diocese to sixteen.[24][32]

Egan's health continued to decline, and he died on July 22, 1814.[33] While 19th-century chroniclers suggest that it "may be said in all truth that Bishop Egan died of a broken heart",[33] modern biographers believe his health troubles more closely resembled tuberculosis.[1][12] Egan was buried in St. Mary's churchyard.[34] In 1869, after the construction of the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul on Logan Square, his remains were removed there and reburied in a crypt along with those of his successor in the see of Philadelphia, Henry Conwell.[35] Conwell-Egan Catholic High School in Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania, is named in honor of Egan and his successor.

Notes

- ^ Although three bishops are typically required for ordination, the Pope may issue a dispensation when co-consecrators are unavailable. See Canon 1014.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Friend 2010.

- ^ a b c Bransom 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ennis 1976, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Ennis 1976, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Loughlin 1909.

- ^ a b c Griffin 1893, p. 4.

- ^ Griffin 1893, p. 5.

- ^ a b Griffin 1893, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Griffin 1893, p. 9.

- ^ Griffin 1893, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Ennis 1976, p. 66.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Ennis 1976, p. 67.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Shea 1888, pp. 617–622.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kurjack 1953, p. 207.

- ^ Carey 1978, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Carey 1978, p. 361.

- ^ Griffin 1893, p. 58.

- ^ a b Ennis 1976, p. 70.

- ^ a b Griffin 1893, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Ennis 1976, p. 68.

- ^ a b Griffin 1893, pp. 68–70, 79.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 74–82.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 87–96.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 103–107.

- ^ Ennis 1976, p. 69.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Shea 1888, p. 661.

- ^ Griffin 1893, p. 112.

- ^ Griffin 1893, pp. 126–127.

Sources

Books

- Bransom, Charles N. (1990). Ordinations of U.S. Catholic Bishops, 1790–1989. Washington, D.C.: United States Catholic Conference. ISBN 978-1-55586-323-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ennis, Arthur J. (1976). "Chapter Two: The New Diocese". In Connelly, James F. (ed.). The History of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Wynnewood, Pennsylvania: Unigraphics Incorporated. pp. 63–112. OCLC 4192313.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Griffin, Martin I. J. (1893). History of Rt. Rev. Michael Egan, D.D., First Bishop of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. OCLC 7637383.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Loughlin, James (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shea, John Gilmary (1888). History of the Catholic Church in the United States. Vol. 2. Akron, Ohio: D.H. McBride & Co. OCLC 3211384.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Articles

- Carey, Patrick (July 1978). "The Laity's Understanding of the Trustee System, 1785–1855". The Catholic Historical Review. 64 (3): 357–376. JSTOR 25020365.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friend, Christine (February 2010). "Philadelphia's First Bishop". Philadelphia Archdiocesan Historical Research Center.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kurjack, Dennis C. (1953). "St. Joseph's and St. Mary's Churches". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 43 (1): 199–209. doi:10.2307/1005672. JSTOR 1005672.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- 1761 births

- 1814 deaths

- 19th-century Roman Catholic bishops

- Roman Catholic bishops of Philadelphia

- American Roman Catholic bishops

- American Roman Catholic clergy of Irish descent

- Irish emigrants to the United States (before 1923)

- Charles University alumni

- 18th-century Irish people

- 19th-century Irish people

- People from County Galway

- People from County Limerick

- Burials at the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul (Philadelphia)