Rapides Cemetery

Rapides Cemetery | |

Sign at entry of Rapides Cemetery in 2012 | |

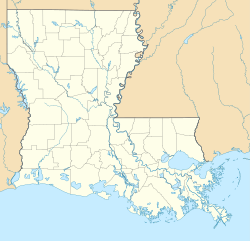

| Location | Hardtner and Main Sts., Pineville, Louisiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°19′0″N 92°26′30″W / 31.31667°N 92.44167°W |

| Area | 7 acres (2.8 ha) |

| Architectural style | Victorian Gothic Funerary |

| NRHP reference No. | 79001088 |

| Added to NRHP | 15 June 1979[1] |

Rapides Cemetery is a historic burial ground located in Pineville, Louisiana at the site of the colonial era Post of Rapides.

History

[edit]The area on the bluffs has been the location of European colonial activity since 1722 and remains an active cemetery.

Colonial era

[edit]The site was the location of a simple Spanish colonial military post in 1722 or 1723. It was in use as graveyard in c. 1769. The Post du Rapide was lightly manned by the French during the French colonial period when the primary activity was trade with the Native Americans. After 1762 when France ceded Louisiana to Spain a small settlement developed around the Post El Rapido. A report to the Spanish Governor O'Reilly in 1769 found 33 whites, 18 slaves, a small Native American village of 26 men and 18 women. In 1799 the settlement had grown to a population of 760 and in 1805 it became known as Pineville. The site that was to become the Rapides Cemetery was in use at that time, known simply as the public cemetery.[2]

After the Civil War

[edit]The Rapides Parish, Louisiana courthouse records were destroyed by fire in 1864 so records of burials before the American Civil War are not extant. In 1872 the Rapides Cemetery Association was founded to clean up, improve and maintain the cemetery. The property was donated to the association in 1874 by Thomas H. Maddox in a deed of 10 acres (4.0 ha). The next year the president of the association Robert P. Hunter signed a deed returning about 3 acres (1.2 ha). As of 1979[update] the graveyard was in use for burials. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 15, 1979.[2]

Funerary ornament

[edit]The cast iron fencing around the three significant plots in the cemetery represent an elaborate example of the use of ornamental Victorian style cast iron graveyard fences rivaling or exceeding those found in New Orleans. The Ashley plot fencing displays its tree motif not just on the gates but in the fencing all the way around the plot. The gothic gates of the Thomas–Flint–Casson plot were made in Philadelphia. T.M. Lincoln and Company of Hartford, Connecticut, manufactured the cast-iron fence for the Mead plot. This fence is composed of ovals, round arches and ball drops. The Mead plot also contains a 25-foot (7.6 m) granite obelisk, the granite for which had to be imported.[2]

Notable interments

[edit]- Pierre Paul Baillio (1771–1824) who built the Kent Plantation House

- Henry Boyce (1797–1873) for whom Boyce, Louisiana is named

- George M. Graham (1807–1891) "Father of Louisiana State University"

- Josiah S. Johnson (1784–1833) US Senator and Congressman

- Isaac Thomas (1784–1859) US Congressman

- John R. Thornton (1846–1917) US Senator

- James Madison Wells (1808–1899) Governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction.[2][3][4]

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System – Rapides Cemetery (#79001088)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Holloman, Ethel G. (15 Jun 1979). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Rapides Cemetery". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved 9 Feb 2020. With 12 photos from 1975 and 1979.

- ^ Barnidge, James L. (1969). "George Mason Graham: The Father of Louisiana State University". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 10 (3): 225–40. JSTOR 4231075.

- ^ Matthews, Jeff (17 Nov 2014). "Old Rapides Cemetery: A 'hidden treasure'". TownTalk. USAToday. Retrieved 9 Feb 2020.

External links

[edit]- Historic Rapides Cemetery Preservation Society

- "First Annual Preservation Project Photo Contest: Prize Winners" (PDF). Historic Rapides Cemetery Preservation Society. 2015

- Rapides Cemetery at Find a Grave