Diana Thater

Diana Thater | |

|---|---|

| Born | May 14, 1962 |

| Education | New York University, Art Center College of Design |

| Known for | Film, Video art, Installation art |

| Awards | John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts fellowship |

Diana Thater (born May 14, 1962, in San Francisco) is an American artist, curator, writer, and educator. She has been a pioneering creator of film, video, and installation art since the early 1990s. She lives and works in Los Angeles, California.[1]

Education and career

Thater studied Art History at New York University and earned her BA in 1984.[2] In 1990 she was awarded an MFA from Art Center College of Design.[2]

Since 2000, Thater has been the artist-in-residence for The Dolphin Project, a non-profit organization that protects cetaceans from slaughter, captivity, and abuse. In 2009, Diana Thater taught art at the European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland.[1]

Work

Thater's work explores the temporal qualities of video and film while literally expanding it into space. She is best known for her site-specific installations in which she manipulates architectural space through forced interaction with projected images and tinted light, such as knots + surfaces (2001) and Delphine (1999) in the Kulturkirche St. Stephani (2009) and the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart (2010).

Thater's primary interest lies in exploring the relationship between humans and the natural world and the distinctions between untouched and manipulated nature. Despite nods to structural film, Thater's underlying reference points are closer to panoramic landscape painting.[3] Thater's stated belief is that film and video are not by definition narrative media, and that abstraction can, and does exist in representational moving images.[4]

Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden

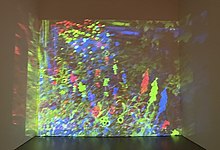

One of Thater's earliest works is Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden (1992), a two part video installation exhibited for the first time in 1992. Thater lived for a time at Claude Monet's former home in Giverny, where she filmed videos on her walks in the home's gardens. The piece is composed of footage of those walks, separated into its component reds, greens and blues; Part I of Oo Fifi is an installation of the three color-separated videos projected on a wall not quite aligned with one another, creating a multi-color effect, while Part II shows the three videos aligned, so the video appears nearly perfectly clear and accurately colored. The third component of the work is wall text listing the scientific names of the plants found in the garden at Monet's home, in addition to a pink light installed in the space where the work is shown.[5][6][7]

Thater had recently finished her MFA and was living in Los Angeles when Oo Fifi was first shown in 1992, over the course of two shows. Thater has said that much of the form of early works like this came from necessity; she was unable to afford screens for the work, so she projected the videos onto a wall in the exhibition space and covered the windows with gels.[5]

Delphine

Delphine is one of Thater's most well-known works and was exhibited not only within the United States but also in several different locations around the world, including France, Germany, Switzerland and Austria.[8] The Delphine exhibition consists of the simultaneous projection of multiple footages of underwater and dolphins.[9] The footages are projected on various surfaces, not just the walls, to create an enveloping and engaging space for the viewers.[9] Thater also placed the projectors in a way that the viewer's silhouette created due to the projector light can physically be part of the work and interact with the subjects within her footages.[9] Unlike some films or videos dealing with animals, Thater's Delphine does not include narration. Thater left out narrations and avoided inserting specific narrative because she believes that animals do not live their lives narratively.[10] Thater wanted to show the animals as they are without enforcing human perspective on them.[10]

Science, Fiction

Exhibited in 2015, Thater's Science, Fiction is a video installation that is divided into two parts.[11] The two parts are placed in separate rooms, but both rooms have blue hue due to the light beams attached on the floor corners.[11] The first part consists of two monitors, facing each other, showcasing footages of planetarium from Griffith Observatory, which is located in Los Angeles.[12] The second part consists of huge box, size of a small room, that has a projection of dung beetles above it and intense yellow light under it.[12] The purpose behind this exhibition was to visually show the recent scientific discovery that dung beetles use starlight during night time to navigate themselves.[11] Through her exhibition, Thater commented on impact of light pollution on wildlife.[11]

Chernobyl

First exhibited in 2011, Thater's Chernobyl showcases multiple footages recorded in Prypiat in Chernobyl.[13] The exhibition consists of simultaneous display of multiple footages of different locations in Prypiat.[13] The center of the exhibition is the footage of a movie theater and all four sides of the movie theater are projected on the gallery space.[13] Over the projection of the movie theater, the other footages, such as buildings, animals and nature, are projected as well.[13] This exhibition is not only about showing negative human impact on nature, but to also show how life still persists even under such condition.[14]

Exhibitions

Since her first solo show in 1991, Thater has staged many exhibitions in museums and galleries in the United States and internationally. Her notable solo shows include Stan Douglas and Diana Thater (1994), Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, Netherlands;[15] China (1995), Renaissance Society, Chicago;[16] electric mind (1996), Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg, Austria;[17] Selected Works 1992–1996 (1996), Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland;[18] Orchids in the Land of Technology (1997), Walker Art Center, Minneapolis;[19] The best animals are the flat animals (1998), MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles;[20] Projects 64: Diana Thater (1998), Museum of Modern Art, New York;[21] Knots + Surfaces (2001-2003), Dia Chelsea, New York;[22] gorillagorillagorilla (2009), Kunsthaus Graz, Austria;[23] Between Science and Magic (2010), Santa Monica Museum of Art (former; now Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles);[24] and Chernobyl (2011-2012), Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia.[25]

Her numerous group exhibitions include the Whitney Biennial (1995,[26] 1997,[27] 2006)[28] and the Carnegie International (1999).[29]

The artist is represented by David Zwirner, New York.

Awards

In 2011, Thater received an Award for Artistic Innovation from the Center for Cultural Innovation in Los Angeles.[30] She used the grant to complete Chernobyl, a large-scale installation project which documents the post-human landscape at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant site in the Ukraine, marking the 25th anniversary of the explosion in 2011.[31] She has been the recipient of other notable awards, including the Phelan Award in Film and Video (2006), a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship (2005),[32] an Étant-donnés Foundation Grant (1996), and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship (1993).

Notable works in public collections

- Nature Black Square #3 (broken glass with four pink flowers) (1990), Whitney Museum, New York[33]

- Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden, Part 1 (1992), Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[34]

- Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden, Part 2 (1992), Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.;[34] and Los Angeles County Museum of Art[35]

- Abyss of Light (1993), Los Angeles County Museum of Art[36]

- The Bad Infinite (1993), Whitney Museum, New York[37]

- Late and Soon (Occident Trotting) (1993), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York[38]

- Moluccan Cockatoo Molly #1 (1995), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[39]

- Moluccan Cockatoo Molly Numbers 1-10 (1995), Art Institute of Chicago[40]

- Scarlet Macaw Crayons (1995), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[41]

- Wicked Witch (1996), Orange County Museum of Art, Costa Mesa, California[42]

- The Best Space is Deep Space (1998), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh;[43] and Los Angeles County Museum of Art[44]

- The Caucus Race (1998), Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles[45]

- Delphine (1999), Art Institute of Chicago;[46] and Kunsthalle Bremen, Germany[47]

- Red-Green-Blue Sun (2000), Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, California[48]

- Six-Color Video Wall (2000), Whitney Museum, New York[49]

- RGB Windows for MOCA (2001), Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles[50]

- Perfect Devotion Six (2006), Los Angeles County Museum of Art[51]

- Blitz (2008), The Broad, Los Angeles[52]

- Untitled (Butterfly Video Wall #1) (2008), Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California[53]

- Untitled (Butterfly Video Wall #2) (2008), San Jose Museum of Art, California[54]

- Female Gyr-Peregrine Falcon (Shumla) (2012), Art Institute of Chicago[55]

References

- ^ a b "Diana Thater Faculty Page at European Graduate School (Biography, bibliography and video lectures)". European Graduate School. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ a b The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2011.

- ^ Liz Kotz in Zoya Kocur, Simon Leung, Theory in Contemporary Art Since 1985, Blackwell Publishing, 2005, p104. ISBN 0-631-22867-5

- ^ "David Zwirner" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ^ a b Butler, Brian (22 February 2021). "What Makes Artist-Run Spaces Flourish". frieze (216). Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Diana Thater: Oo Fifi, Five Day's in Claude Monet's Garden, Part I and II, 1992". 1301pe. Archived from the original on 17 September 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "A Conversation with Diana Thater". Unframed LACMA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 7 December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "DIANA THATER STUDIO". www.thaterstudio.com. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ a b c "Diana Thater | icaboston.org". www.icaboston.org. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ a b "DIANA THEATER // THE SYMPATHETIC IMAGINATION". THE SEEN | Chicago's International Online Journal. 2016-09-20. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Ken (2015-01-29). "Diana Thater: 'Science, Fiction'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ a b "Diana Thater, reviewed by Jonathan T.D. Neil / ArtReview". artreview.com. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Roberta (2012-11-15). "Diana Thater: 'Chernobyl'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ "Art Review, Diana Thater: Chernobyl, David Zwirner, New York, 2012 / ArtReview". artreview.com. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ "Stan Douglas and Diana Thater". Kunstinstituut Melly. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "China". Renaissance Society. University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "electric mind". Salzburger Kunstverein. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Selected Works 1992-1996". Kunsthalle Basel (in German). Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Staniszewski, Mary Anne (May 1997). "Diana Thater". Artforum. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "The best animals are the flat animals". MAKCenter. Schindler House. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Projects 64: Diana Thater". MoMA. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Knots + Surfaces". DiaArt. Dia Art Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "gorillagorillagorilla". Kunsthaus Graz. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Diane Thater: Between Science and Magic". Santa Monica Museum of Art. Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Chernobyl". IMA. Institute of Modern Art. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Whitney Biennial 1995". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Whitney Biennial 1997". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Whitney Biennial 2006". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Siegel, Katy (January 2000). "1999 Carnegie International". Artforum. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Center for Cultural Innovation Press Release

- ^ Diana Thater - Center for Cultural Innovation

- ^ gf.org Archived 2006-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nature Black Square #3 (broken glass with four pink flowers)". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden, Parts 1 and 2". Hirshhorn. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden, Part 2". LACMA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Abyss of Light". LACMA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "The Bad Infinite". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Late and Soon (Occident Trotting)". Guggenheim. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Moluccan Cockatoo Molly #1". MetMuseum. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Moluccan Cockatoo Molly Numbers 1-10". ArtIC. Art Institute of Chicago. 1995. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Scarlet Macraw Crayons". MetMuseum. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Wicked Witch". OCMA. Orange County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ "The best space is the deep space". CMOA. Carnegie Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "The Best Space is Deep Space". LACMA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "The Caucus Race". MOCA. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Delphine". ArtIC. Art Institute of Chicago. 1999. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Delphine". Kunsthalle Bremen (in German). Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Red-Green-Blue Sun". Berkeley. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ "Six-Color Video Wall". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "RGB Windows for MOCA". MOCA. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Perfect Devotion Six". LACMA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Blitz". The Broad. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Untitled (Butterfly Video Wall #1)". SBMA. Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ "Untitled (Butterfly Video Wall #2)". SJMusArt. San Jose Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Female Gyr-Peregrine Falcon (Shumla)". ArtIC. Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

External links

- Diana Thater. Faculty page at European Graduate School (Biography, filmography, photos and video lectures)

- Diana Thater at David Zwirner. Gallery. New York. (Biography, press and selected Works)

- Diana Thater Studio

- Diana Thater's GorillaGorillaGorilla at Kunsthaus Graz, 2009

- Diana Thater's knots + surfaces at Dia, 2001

- Diana Thater at Carnegie Museum of Art

- The Dolphin Project

- Hauser & Wirth, London & Zurich

- Diana Thater's profile at Kadist Art Foundation