Economics of car use

Compared to other popular modes of passenger transportation, the car has a relatively high cost per person-distance traveled.[1] The income elasticity for cars ranges from very elastic in poor countries, to inelastic in rich nations. [2] The advantages of car usage include on-demand and door-to-door travel, and are not easily substituted by cheaper alternative modes of transport, with the present level and type of auto specific infrastructure in the countries with high auto usage.

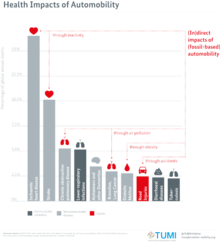

Public costs related to the car are several including congestion and effects related to emissions.

Private benefits

[edit]The benefits of using a car differ by many factors, in regard to location and culture. One general benefit is availability of use which, when coupled with public support via infrastructure (such as roads or fuel stations), can allow highly flexible movement and transportation. Because public transportations are not as well omnipresent and normally don't run at certain day periods, they might not be an option. Car allows a certain freedom of movement, that other means of transport do not. Another private benefit car owners enjoy, is comfort. The car allows the transportation of the driver (and passengers) from a certain point A, to another point B, within an acclimatized and protected interior.

Private costs

[edit]According to the RAC[3] motorists in the UK spend an average of GBP 5,000 (US$ 9,000) per year on their car, or roughly 1/3 of the average net wage; while the RACV suggests[4] roughly AUD $10,000 per year, compared to AUD $26,000 median income among all Australian adults or AUD $66,000 median income among all Australian households.[5] This situation is reflected in most other Western nations. For the average car owner, depreciation constitutes about half the cost of running a car.[3] The typical motorist underestimates this fixed cost by big margin, or even ignores it altogether, according to a survey by the RAC.[6]

There are a number of reasons for the high cost of car transport:

- The typical private car spends most of its lifetime idle and for some vehicles, depreciation is a significant proportion of the total cost.

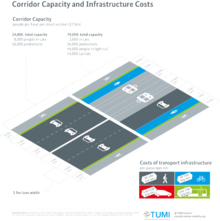

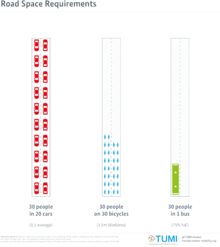

- Compared to bulk-carrying vehicles such as airplanes, buses, and trains, individual vehicles have worse economies of scale.

- Capacity utilisation is low. The average occupancy of cars is below 1.5 passengers in most parts of the world. Measures such as High-occupancy vehicle lanes try to address this issue.

- The car energy efficiency is one of the lowest amongst several means of transportation.

- Government taxes[7]

The costs of running a car can be broken down as follows (in no particular order):

- Fuel (including fuel tax)

- Repairs

- Maintenance

- Financing

- Insurance

- Parking

- Tolls on Roads, Bridges and Tunnels

- Vehicle tax

- Vehicle inspection

- Registration

- Car washes

In the UK car travel has steadily become cheaper over the past five decades. According to the Department for Transport, the real cost of running a car has dropped by 9% between 1980 and 2007. [8] This development is in part due to more cost effective manufacturing technologies, and in part due to engines becoming more fuel-efficient.

Of the annual running costs of a car for an average person, 70–75%[9] are fixed costs (with respect to distance travelled): a 10% increase or decrease in usage should result in a 2.5–3% increase or decrease in annual running costs.

Some of the annual running costs of a car, which are important in the economics of ownership, concern the service life; a major factor for this deals with the uncertainty of the car lifespan. Many cars, particularly taxis, have achieved very high-mileage (miles driven) status, indicating that maintenance which can extend the car service life may reduce the overall running cost.

Public benefits

[edit]In countries deprived from wide door-to-door public transport and with low density, such as Australia, the automobile plays an important role on the mobility of citizens. Public transport, by comparison, becomes increasingly uneconomic with lower population densities. Hence cars tend to dominate in rural and suburban environments with public economic gains.

The automobile industry, mainly in the beginning of the 20th century when the high motorization rates were not an issue, had also an important public role, which was the creation of jobs. In 1907, 45,000 cars were produced in The United States, but 28 years later in 1935 3,971,000 were produced, nearly 100 times as many. This increase in production required a large, new work force. In 1913 13,623 people worked at Ford Motor Company, but by 1915 18,028 people worked there.[10] Bradford DeLong, author of The Roaring Twenties, tells us that, "Many more lined up outside the Ford factory for chances to work at what appeared to them to be (and, for those who did not mind the pace of the assembly line much, was) an incredible boondoggle of a job.[10]" There was a surge in the need for workers at big, new high-technology companies such as Ford. Employment largely increased.

Public costs

[edit]

The external costs of automobiles, as similarly other economic externalities, are the measurable costs for other parties except the car proprietor, such costs not being taken into account when the proprietor opts to drive their car. According to the Harvard University,[11] the main externalities of driving are local and global pollution, oil dependence, traffic congestion and traffic accidents; while according to a meta-study conducted by the Delft University[12] these externalities are congestion and scarcity costs, accident costs, air pollution costs, noise costs, climate change costs, costs for nature and landscape, costs for water pollution, costs for soil pollution and costs of energy dependency. The existence of the car allows on-demand travel, given, that the necessary infrastructure is in place. This infrastructure represents a monetary cost, but also cost in terms of common assets that are difficult to represent monetarily, such as land use and air pollution.

The car allowed a shift in residential locations, as civil engineering grew to handle the infrastructure requirements, allowing the growth of the suburbs. As shown by Ford, the car changed the economic landscape. The efforts to resolve costs that have ensued from the influence of the car, such as pollution and fuel costs, will have a similar impact on the economic landscape. For instance, providing carpooling lanes to cars with multiple passengers has received attention as it helps reduce traffic. Sharing one or more cars between many people reduces the fixed costs per person and limits extraneous vehicles; the use of fleet vehicles affords savings through joint use of a set of autos by a very large group of persons either for business or pleasure.

Since cars demand a high land use, they become increasingly uneconomic with higher population densities. This can either manifest itself in higher costs of driving in densely populated areas (parking fees and road pricing), or, in the absence of a price mechanism, in a shortage in the form of traffic jams.

A study attempted to quantify the costs of cars (i.e. of car-use and related decisions and activity such as production and transport/infrastructure policy) in conventional currency, finding that the total lifetime cost of cars in Germany is between 0.6 and 1.0 million euros with the share of this cost born by society being between 41% (€4674 per year) and 29% (€5273 per year). This suggests that cars consume "a large share of disposable income", creating "complexities in perceptions of transport costs, the economic viability of alternative transport modes, or the justification of taxes".[13]

See also

[edit]- Automotive industry (includes production statistics)

- Car costs

- Effects of the car on societies

References

[edit]- ^ Diesendorf, Mark. "The Effect of Land Costs on the Economics of Urban Transportation Systems" (PDF). Proceedings of Third International Conference on Traffic and Transportation Studies (ICTTS2002). pp. 1422–1429. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-19. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ Dargay, Joyce; Dermot Gately (1998-12-21). "Income's effect on car and vehicle ownership, worldwide: 1960–2015". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 33 (2). Elsevier Science: 101–138. doi:10.1016/S0965-8564(98)00026-3.

- ^ a b Osborne, Hilary (2006-10-20). "Cost of running a car 'exceeds £5,000'". The Guardian. London.

- ^ How much does it cost to own a car?

- ^ The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey

- ^ Meek, James (2004-12-20). "The slow and the furious". The Guardian. London.

- ^ M. Maibach, C. Schreyer, D. Sutter (INFRAS), Delft University. "Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnett, Antony (2007-03-21). "How to make the countryside sustainable". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Based on the breakdown of costs given in the above mentioned RACV study

- ^ a b DeLong, Bradford. "The Roaring Twenties." Slouching Towards Utopia? The Economic History of the Twentieth Century". Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ IAN W. H. PARRY; et al. (June 2007). "Automobile Externalities and Policies" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature: 30. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- ^ M. Maibach; et al. (February 2008). "Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector" (PDF). Delft, February. p. 332. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- ^ Gössling, Stefan; Kees, Jessica; Litman, Todd (1 April 2022). "The lifetime cost of driving a car". Ecological Economics. 194: 107335. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107335. ISSN 0921-8009.