Ruzbahan

Ruzbahan | |

|---|---|

| Native name | روزبهان |

| Born | 10th-century Daylam |

| Died | 957 Near Baghdad |

| Allegiance | Buyid dynasty (until 955) |

Ruzbahan ibn Vindadh-Khurshid (Persian: روزبهان بن ونداد خورشید), better known as Ruzbahan (also spelled as Rezbahan), was a Daylamite military officer who served the Buyid dynasty. A native of Daylam, Ruzbahan began serving the Buyids at an unknown date and quickly rose into high ranks. After constant pressure from king Mu'izz al-Dawla to conquer Batihah, he, along with his two brothers, started a rebellion lasting from 955 to 957. After the end of the rebellion, Ruzbahan was imprisoned and shortly executed.

Biography

Early life and career

Ruzbahan was the son of a certain Vindadh-Khurshid, and had two brothers named Asfar and Bullaka. Like his Buyid overlords, Ruzbahan was a Daylamite. However, unlike the Buyids, he probably belonged to a family of noble origin. When the Buyid ruler Mu'izz al-Dawla conquered Iraq in 945, Ruzbahan was appointed as the tax collector of the Sawad.[1] Ruzbahan was originally a low rank officer who served a Buyid officer named Musa Fayadhah.[2] However, under Mu'izz al-Dawla he rapidly rose to higher ranks and became a favourite of Mu'izz al-Dawla.[3]

In 948/949, during negotiations between Mu'izz al-Dawla's and the Sallarid ruler Marzuban's ambassadors, Marzuban was greatly insulted, and became enraged; he tried to avenge himself by marching towards Ray, which was under the control of Mu'izz al-Dawla's brother Rukn al-Dawla. Rukn al-Dawla, however, managed to trick and slow Marzuban down by diplomatic means,[4] while he was receiving aid from Mu'izz al-Dawla, who sent an army under Sebük-Tegin, which also included other officer such as Ruzbahan, Burarish, Ibrahim ibn al-Mutawwaq, 'Ammar "the Mad", and Ahmad ibn Salih Kilabi.[5] However, when the army was close to Dinavar, Burarish, who disliked Sebük-Tegin and refused to obey the orders of the latter, mutinied along with most of the Daylamites in the army, except Ruzbahan and other Daylamite officers. Burarish shortly heavily wounded Sebük-Tegin, who, however, managed to flee from the latter.[5] For unknown reasons, Burarish shortly fled, but was quickly captured by the supporters of Sebük-Tegin.[5] The army of Sebük-Tegin then continued to Ray, and at the same time, reinforcements arrived from Shiraz. Rukn al-Dawla shortly managed to defeat and capture Marzuban.

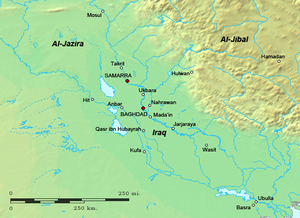

In 949, Mu'izz al-Dawla sent Ruzbahan on an expedition against the Batihah ruler 'Imran ibn Shahin. Ruzbahan discovered 'Imran's location and attacked him, but was heavily defeated and forced to withdraw. 'Imran then became even more bold, with his subjects demanding protection money from anyone, including government officials, that crossed their path, and the path to Basra by water was effectively closed off. Mu'izz al-Dawla, after receiving numerous complaints from his officers, sent another army in 950 or 951, under the joint command of Ruzbahan and the amir's vizier al-Muhallabi.

Ruzbahan, who disliked the vizier, convinced him to directly attack 'Imran. He kept his forces in the rear and fled as soon as fighting between the two sides began. 'Imran used the terrain effectively, laying ambushes and confusing al-Muhallabi's army. Many of the vizier's soldiers died in the fighting and he himself only narrowly escaped capture, swimming to safety. Mu'izz al-Dawla then came to terms with 'Imran, acceding to his terms. Prisoners were exchanged and 'Imran was made a vassal of the Buyids, being instated as governor of the Batihah.

Rebellion

Peace lasted for approximately five years between the two sides. During this period, a marriage was being arranged between a daughter of Ruzbahan and Mu'izz al-Dawla's son Izz al-Dawla.[6] A false rumor of Mu'izz al-Dawla's death in 955, however, prompted 'Imran to seize a Buyid convoy traveling from Ahvaz to Baghdad. Mu'izz demanded that the items confiscated be returned, at which point 'Imran returned the money gained, but kept the goods taken. Ruzbahan was then for a third time sent to the swamp, but shortly revolted along with his brother Asfar and spared 'Imran from a new attack.[7][3] Ruzbahan's other brother, Bullaka, joined the rebellion and revolted at Shiraz. Ruzbahan was further joined by the Daylamite soldiers of al-Muhallabi. Ruzbahan quickly marched towards Ahvaz, where al-Muhallabi was preparing a counter-attack. However, the troops of al-Muhallabi quickly deserted him and joined Ruzbahan.[2] Ruzbahan then marched towards Mu'izz al-Dawla, who sent an army under his Daylamite general Shirzil, who, however, shortly, along with his army, joined the rebellion of Ruzbahan. In 956, Mu'izz al-Dawla left Baghdad in order to fight Ruzbahan himself. Meanwhile, the Hamdanid ruler Nasir al-Dawla used this opportunity to seize Baghdad.

In 957, Ruzbahan fought a final battle against Mu'izz al-Dawla. Ruzbahan almost managed to win the battle, but was defeated by Mu'izz al-Dawla's ghulams. The defeat marked the end of Ruzbahan's rebellion.[8] Ruzbahan was captured during the battle and was imprisoned in a fortress known as Sarat.[9]

Captivity and death

The Daylamite supporters of Ruzbahan then began planning to capture the fortress and rescue Ruzbahan. However, Abu'l-Abbas Musafir, an officer of Mu'izz al-Dawla, managed to discover of the Daylamite's plan, and quickly urged Mu'izz al-Dawla to have Ruzbahan killed. Mu'izz al-Dawla, however, did not agree with him. A number of Mu'izz al-Dawla's officer shortly told him the same, which made him agree with them. When it became night, the guards of Mu'izz al-Dawla took Ruzbahan to the Tigris river, where he was drowned.[10][9]

References

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 37.

- ^ a b Amedroz & Margoliouth 1921, p. 173.

- ^ a b Donohue 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 234.

- ^ a b c Amedroz & Margoliouth 1921, p. 122.

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 64.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 221.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 217.

- ^ a b Amedroz & Margoliouth 1921, p. 178.

- ^ Kabir 1964, p. 13.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (1975). "Iran under the Būyids". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–305. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Donohue, John J. (2003). The Buwayhid Dynasty in Iraq 334 H./945 to 403 H./1012: Shaping Institutions for the Future. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12860-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kabir, Mafizullah (1964). The Buwayhid Dynasty of Baghdad, 334/946-447/1055. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Amedroz, Henry F.; Margoliouth, David S., eds. (1921). The Eclipse of the 'Abbasid Caliphate. Original Chronicles of the Fourth Islamic Century, Vol. V: The concluding portion of The Experiences of Nations by Miskawaihi, Vol. II: Reigns of Muttaqi, Mustakfi, Muzi and Ta'i. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.