Henry I, Duke of Brabant

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2023) |

Henry I | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Brabant Duke of Lothier | |

| |

| Born | c. 1165 |

| Died | 5 September 1235 Cologne, Kingdom of Germany, Holy Roman Empire |

| Buried | St. Peter's Church, Leuven |

| Noble family | House of Reginar |

| Spouse(s) | Matilda of Boulogne Marie of France |

| Issue | Maria of Brabant, Holy Roman Empress Adelaide Margaret Matilda Henry II, Duke of Brabant Godfrey Elizabeth Marie |

| Father | Godfrey III, Count of Leuven |

| Mother | Margaret of Limburg |

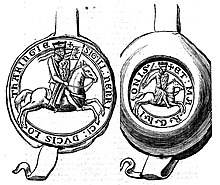

Henry I (Template:Lang-nl, Template:Lang-fr; c. 1165 – 5 September 1235), named "The Courageous", was a member of the House of Reginar and first duke of Brabant from 1183/84 until his death.

Early life

Henry was possibly born in Leuven (Louvain), the son of Count Godfrey III of Louvain[1] and his wife Margaret, daughter of Duke Henry II of Limburg. His father also held the title of a landgrave of Brabant, duke of Lower Lorraine and margrave of Antwerp. Henry early appeared as a co-ruler of his father. In 1180,[2] he married Matilda of Boulogne, daughter of Marie of Boulogne and Matthew of Alsace[1] and on this occasion received the County of Brussels from his father. He acted as a regent while Count Godfrey III went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem from 1182 to 1184.[citation needed]

Career

In 1183, Henry took the title of duke of Brabant. Upon the death of his father in 1190, King Henry VI confirmed the elevation of Brabant, while he de facto abolished the Duchy of Lower Lorraine by creating the empty title of a Duke of Lothier. Duke Henry sought to expand his power and soon picked several quarrels with the Count Baldwin V of Hainaut. He also was in opposition to the German king (emperor from 1191) when his brother Albert of Louvain was elected bishop of Liège and murdered shortly afterwards.

Further conflicts with Duke Henry III of Limburg and Count Otto I of Guelders followed, before in mid-1197 Henry of Brabant joined the Crusade of Henry VI as one of the leaders. In October of the same year he took part in the recapture of Beirut and, then moved to Jaffa with the crusaders: however, before reaching the city he got news of the death of the King of Jerusalem, Henry II, Count of Champagne, and he returned to Acre. Here he acted as regent until the arrival of the new king, Amalric II.

Back in Germany after the emperor's death in September 1197, Duke Henry supported the election of the Welf candidate Otto IV, the fiancé of his daughter Maria, who rivalled with the Hohenstaufen scion Philip of Swabia. He fought against Philip's seconders Count Dirk VII of Holland and Count Otto of Guelders, however, he switched sides in 1204,[3] when he and King Philip II of France backed Philip against Otto. In 1208, after the assassination of Philip, Henry was proposed as successor by King Philip II. In the war which followed, he finally reached a reconciliation with Emperor Otto IV. Together they fought against King Philip in the 1214 Battle of Bouvines,[4] but the two were defeated.

In 1213, Duke Henry also suffered a heavy defeat against the Bishopric of Liège in the Battle of Steppes.[5] From 1217 to 1218 he joined the Fifth Crusade to Egypt.[6]

Under Henry I, there was town policy and town planning. His attention went out to those regions that lent themselves to the extension of his sovereignty and in some locations he used the creation of a new town as an instrument in the political organisation of the area. Among the towns to which the duke gave city rights and trade privileges were 's-Hertogenbosch and Eindhoven.

In 1234, he participated in the Stedinger Crusade. In 1235, Emperor Frederick II appointed Henry to travel to England to bring him his fiancée Isabella, daughter of King John of England. Henry fell ill on his way back and died at Cologne. He was buried in Saint Peter's Church at Leuven where his Late Romanesque effigy can still be seen.

Marriages

Henry had six children by his first marriage with Mathilde of Boulogne:

- Maria (c. 1190–1260), married in Maastricht after May 19, 1214 Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor,[1] married July 1220 William I, Count of Holland[7]

- Adelaide (b. c. 1190), married 1206 Arnold III, Count of Looz, married 1225 William X of Auvergne (c. 1195–1247), married before April 21, 1251 Arnold van Wesemaele (d. aft. 1288)

- Margaret (1192–1231), married January 1206 Gerhard III, Count of Guelders (d. 1229)[8]

- Mathilde (c. 1200–1267), married in Aachen in 1212 Henry VI, Count Palatine of the Rhine (d. 1214), married on December 6, 1214 Floris IV, Count of Holland[8]

- Henry II of Brabant (1207–1248)[8]

- Godfrey (1209–1254), Lord of Gaesbeek, married Marie van Oudenaarde

His second marriage was at April 22, 1213 in Soissons to Marie, daughter of King Philip II of France.[9] They had two children:

- Ysabeau (Elizabeth) (d. 1272), married in Leuven March 19, 1233 Count Dietrich of Cleves, Lord of Dinslaken (c. 1214–1244),[10] married 1246, Gerhard II, Count of Wassenberg (d. 1255)

- Marie, died young

Death, burial, and tomb

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (January 2023) |

In 1235, Henry I was commissioned by the German emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen to accompany the imperial fiancée Isabella Plantagenet from England to Germany. However, he died en route in Cologne, before he could complete his assignment.

His tomb in Saint Peter's Church, Leuven is the oldest surviving of its kind. The image of Henry I has been idealized in the relief: he is depicted as a smiling young man. In addition, he lies on a high base, wears a long robe and the duke's cloak, and holds a scepter; his left hand plays with the cord of the mantle. The archangels Raphaël and Michael wave the censer at his head. In addition to the tomb of Hendrik I van Brabant, there are also the tombs of his wife Mathilde van Boulogne and his daughter, Maria van Brabant.

Originally, the tomb was at the altar. This was a privilege reserved only for prominent families and high clergy. The initially Romanesque church was replaced by a Gothic church in the fifteenth century. It was then that Hendrik's grave was moved and given a place of honor in front of the high altar. During the French occupation in the eighteenth century, the grave was destroyed and its remains were buried under the tower.

Only in the mid-19th century was the burial monument restored and placed in the chapel of Saint John of Latheran. The bones of Hendrik I were dug up in 1929 and only a few decades later, namely in 1998, were they put back in the tomb. In the meantime, the monument has been relocated and is back in its original place: in front of the high altar.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b c George 1875, p. table XXIX.

- ^ Lambert of Ardres 2007, p. 229.

- ^ Wihoda 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Wilkinson 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Schnerb 2010, pp. 309–311.

- ^ Wilson 2021, p. 114.

- ^ Wilkinson 2012, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Baldwin 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Pollock 2015, p. 53.

- ^ Behm 1908, p. 41.

- ^ 'Grafmonument van hertog Hendrik I', Erfgoedplus.be (https://www.erfgoedplus.be/details/24062A51.priref.17497)

Sources

- Baldwin, Philip B. (2014). Pope Gregory X and the Crusades. The Boydell Press.

- Behm, Otto (1908). Die ältesten clevischen chroniken und ihr verhältnis zu einander: Wisseler (in German). Druck von Emil Eisele.

- George, Hereford Brooke (1875). Genealogical Tables Illustrative of Modern History. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

- Lambert of Ardres (2007). The History of The Counts of Guines and Lords of Ardres. Translated by Shopkow, Leah. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Pollock, M. A. (2015). Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy, 1204-1296. The Boydell Press.

- Schnerb, Bertrand (2010). "Battle of Steppes". In Rogers, Clifford J. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 309–311.

- Wihoda, Martin (2016). Vladislaus Henry: The Formation of Moravian Identity. Brill.

- Wilkinson, Louise J. (2012). Eleanor de Montfort: A Rebel Countess in Medieval England. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Wilson, Jonathan (2021). The Conquest of Santarém and Goswin’s Song of the Conquest of Alcácer do Sal. Routledge.

- Chronique des Ducs de Brabant, Adrian van Baerland, Antwerp (1612).