Fred Snodgrass

| Fred Snodgrass | |

|---|---|

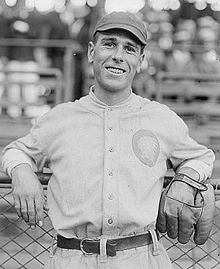

Snodgrass in 1916 | |

| Outfielder | |

| Born: October 19, 1887 Ventura, California, U.S. | |

| Died: April 5, 1974 (aged 86) Ventura, California, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| June 4, 1908, for the New York Giants | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 5, 1916, for the Boston Braves | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .275 |

| Home runs | 11 |

| Runs batted in | 353 |

| Teams | |

Frederick Carlisle Snodgrass (October 19, 1887 – April 5, 1974) was an American center fielder in Major League Baseball from 1908 to 1916. He is best known for dropping a key fly ball in the 1912 World Series.

New York Giants

Early years

Snodgrass was originally a catcher when he joined the New York Giants in 1908 at twenty years old. He made his major league debut on June 4, and collected his first major league hit and run batted in off the St. Louis Cardinals' Slim Sallee.[1]

With Hall of Famer Roger Bresnahan manning catching duties for manager John McGraw, Snodgrass saw very little action. On December 12, 1908, the Giants traded Bresnahan to the St. Louis Cardinals for Red Murray, Bugs Raymond and Admiral Schlei. Snodgrass appeared in his first two games of 1909 behind the plate (hitting his first career home run off Jake Boultes in his second game[2]), but Schlei and rookie Chief Meyers shared catching duties in 1909, with Snodgrass shifting to the outfield.

Snodgrass began to emerge as a star in 1910, finishing fourth in the National League with a career high .321 batting average his first full season with the Giants. In 1911, his average dipped to .294, however, he drove in a career best 77 runs. He also stole 51 of the 347 bases McGraw's Giants stole that season. Along with Fred Merkle and Larry Doyle, Snodgrass formed a core of sluggers behind aces Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard that led the Giants to three straight pennants from 1911 to 1913.

Snodgrass' regular season success did not translate to success on the World Series, however. Philadelphia Athletics catcher Ira Thomas caught the usually speedy runner stealing twice in the first game.[3] Jack Coombs, who led the American League with 28 wins, along with Hall of Famers Eddie Plank and Chief Bender, held Snodgrass to just two hits with seven strikeouts in nineteen at bats over the course of the Giants' six game loss to the A's in the 1911 World Series.[4]

1912 World Series

In 1912, Snodgrass scored a career high 91 runs for a Giants team that won 103 games on its way to a second consecutive pennant. The Boston Red Sox held a three games to two lead in the 1912 World Series, as it headed into its seventh game (game 2 ended in a tie[5]). Facing elimination, the Giants faced Smoky Joe Wood, who went 34-5 with a 1.91 earned run average and ten shutouts for the AL champions, and won games one[6] and four[7] of the World Series. Toeing the rubber for the Giants was rookie Jeff Tesreau, the losing pitcher in both of those games.

To the surprise of the Fenway crowd, the Giants lit up Wood for six runs in the first inning. Snodgrass drove in the first two Giants runs with a double to right that scored Josh Devore and Larry Doyle. He then came around to score the third run of the inning on Fred Merkle's single. Wood lasted just the one inning, while Tesreau pitched a complete game to even the series for the Giants.[8]

Game eight featured a rematch between game five starters Christy Mathewson and Hugh Bedient. In game five, the Bosox rookie outdueled Mathewson, 2-1,[9] and game eight was following a similar pitchers' duel storyline. Bedient exited after seven innings trailing 1-0, but in the bottom of the seventh, Olaf Henriksen's run-scoring double tied the game. Wood returned to the mound for the Red Sox in the eighth, and held the Giants scoreless heading into the tenth inning. Snodgrass led off the tenth by grounding back to the pitcher, but Red Murray followed with a double, and was driven in by the next batter, Fred Merkle.

The Giants headed into the bottom of the tenth with a 2-1 lead on the verge of winning their first World Series since 1905. Pinch hitter Clyde Engle led off the bottom of the tenth with a fly ball toward right-center. The ball was hit more toward Murray in right field, but Snodgrass, coming from center field, called Murray off. He then dropped it for a two base error. He proceeded to make a spectacular game-saving catch on the next play, a deep fly ball to center by Harry Hooper, but Tris Speaker then followed with a single to tie the game. A Larry Gardner sacrifice fly drove in the World Series winning run for the Red Sox.[10]

Giants manager John McGraw was not among those who blamed Snodgrass for the loss. In his book My Thirty Years in Baseball, McGraw remarked, "Often I have been asked what I did to Fred Snodgrass after he dropped that fly ball in the World Series of 1912...I will tell you exactly what I did: I raised his salary $1,000."[11] Just the same, the error became known as "Snodgrass's Muff" and also, the "$30,000 Muff."[12]

1913 and 1914

While Snodgrass batted a solid .291 with 49 runs batted in and 65 runs scored in 1913, McGraw decided to use Tillie Shafer, who could play multiple positions, in center field in place of Snodgrass in the 1913 World Series. The strategy didn't work, as the Giants were beaten in five games by the A's. Snodgrass had one hit in three at bats.[13] In 1914, the Giants' record dipped to 84-70, as they missed their first World Series in four years.

Snodgrass' final at bat as a Giant came on August 17, 1915 as a pinch hitter.[14] After the game, he was released with a .194 batting average, with first baseman Fred Merkle assuming center field duties over the rest of the season.

Boston Braves

Shortly after his release from the Giants, Snodgrass signed with the Boston Braves. He rebounded nicely for his new club, batting .278 the rest of the season. He returned to the Polo Grounds for a three game set September 6 through 7, and collected one hit in twelve at bats.

1916 was Snodgrass' final major league season. The Braves finished in third place, three games ahead of the Giants, with a 89-63 record. For his part, Snodgrass batted .249 with 32 runs batted in, while playing his usual steady center field for the Braves. In 1917, Snodgrass returned home to California, and spent one final season with the Pacific Coast League's Vernon Tigers before retiring from the game.

Personal life

Snodgrass was born in Ventura, California, the son of Andrew Jackson Snodgrass and his wife Addie (McCoy). He married the former Josephine Vickers on August 12, 1909. While playing for the Giants, he and Josephine lived in New York City. In 1912, Nellie Frakes sued him for $75,000 for breach of promise (to marry her) and seduction.[15] After Snodgrass petitioned for a change of venue to Ventura, the Los Angeles Times reported that Nellie Frakes impressed the audience with her "comeliness" (and smiled often to Mrs. Snodgrass) but lost the case to Snodgrass.[16] He and Josephine had two daughters, Eleanor Jean in 1917, and Elizabeth "Betty" Ann in 1921.

Snodgrass attended St. Vincent's College in Los Angeles before joining the Giants. Later, he became a successful banker and was a popular city councilman and mayor in Oxnard, the largest city in his native Ventura County.

In the early 1960s, a half-century after his infamous dropped ball, Snodgrass was immortalized in the Lawrence Ritter 1966 book The Glory of Their Times, which featured oral accounts by 26 of the game's oldest surviving players. Snodgrass' recount of the error in an interview with Ritter was included in Ritter's renowned baseball book.[17]

I yelled that I'll take it, and waved Murray off and, well, I dropped the darn thing.

His error in the 1912 World Series remained with him until his death. When he died on April 5, 1974, his obituary in The New York Times was headlined "Fred Snodgrass, 86, Dead; Ball Player Muffed 1912 Fly."[17][18] Snodgrass was buried in Ventura's Ivy Lawn Memorial Park.

See also

References

- ^ "St. Louis Cardinals 7, New York Giants 5". Baseball-Reference.com. June 4, 1908.

- ^ "New York Giants 12, Boston Doves 5". Baseball-Reference.com. June 24, 1909.

- ^ "1911 World Series, Game 1". Baseball-Reference.com. October 14, 1911.

- ^ "1911 World Series". Baseball-Reference.com. October 14–26, 1911.

- ^ "1912 World Series, Game 2". Baseball-Reference.com. October 9, 1912.

- ^ "1912 World Series, Game 1". Baseball-Reference.com. October 8, 1912.

- ^ "1912 World Series, Game 4". Baseball-Reference.com. October 11, 1912.

- ^ "1912 World Series, Game 7". Baseball-Reference.com. October 15, 1912.

- ^ "1912 World Series, Game 5". Baseball-Reference.com. October 12, 1912.

- ^ "1912 World Series, Game 8". Baseball-Reference.com. October 16, 1912.

- ^ George Plimpton (1992). The Norton Book of Sports. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 310. ISBN 0393030407. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

fred-snodgrass 1912 book.

- ^ Wilbert, Warren N. (2002). A Cunning Kind of Play: the Cubs-Giants Rivalry, 1876–1932. McFarland. p. 122. ISBN 0786411562. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ "1913 World Series". Baseball-Reference.com. October 7–11, 1913.

- ^ "Brooklyn Robins 3, New York Giants 2". Baseball-Reference.com. August 17, 1915.

- ^ "Snodgrass Will Fight Breach of Promise Suit". Sacramento Union. December 19, 1912.

- ^ Lynch, Mike (March 8, 2010). "More Interesting Research Finds". Baseball Prospectus.

- ^ a b Gay, Timothy M. (2005). Tris Speaker: The Rough-and-Tumble Life of a Baseball Legend. University of Nebraska Press. p. 19. ISBN 0803222068.

- ^ "Fred Snodgrass, 86, Dead; Ball Player Muffed 1912 Fly". The New York Times. April 6, 1974.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Fred Snodgrass - Baseballbiography.com

- Fred Snodgrass at Society for American Baseball Research

- Fred Snodgrass at Find a Grave

- 1887 births

- 1974 deaths

- Major League Baseball center fielders

- New York Giants (NL) players

- Boston Braves players

- Major League Baseball controversies

- Los Angeles Angels (minor league) players

- Vernon Tigers players

- Sportspeople from Ventura, California

- Mayors of places in California

- Baseball players from Oxnard, California

- Burials at Ivy Lawn Cemetery

- Los Angeles High School alumni