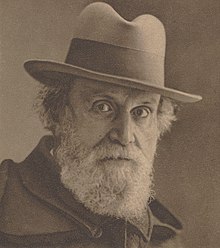

Tadeusz Stefan Zieliński

Tadeusz Stefan Zieliński | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 14, 1859 |

| Died | May 8, 1944 (aged 84) |

Tadeusz Stefan Zieliński (Polish: [taˈdɛ.uʐ ʑɛˈlij̃skʲi]; Russian: Фадде́й Фра́нцевич Зели́нский; [Faddei Frantsevich] September 14, 1859 – May 8, 1944) was a prominent Polish classical philologist, historian, and translator of Sophocles, Euripides and other classical authors into Russian.[1] His most well-known works are Die Gliederung der altattischen Komoedie, Tragodumenon libri tres, and Iresione, the last of which is a collection of essays.[2]

Life and career

He was born on 14 September 1859 in Skrzypczyńce, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) to father Franciszek and mother Ludwika (née Grudzińska), both of them of Polish descent.[3] Between 1869 and 1876 he attended secondary school in Saint Petersburg and subsequently in the years 1876–1881 he studied in Leipzig, Munich and Vienna. In 1880 he earned his doctorate from the University of Leipzig for his dissertation, Die Gliederung der altattischen Komoedie.[3] He was author of works on the history of ancient Greek culture and religion, classical education, and popularization of classical studies (published largely in Russian and German).

In 1884 he became a professor at the University of St. Petersburg, and following Polish independence he held the chair of Classical Studies at Warsaw University for 17 years (1922–1939) during the interwar period.[4] He was the recipient of honorary doctorates from the Jagiellonian University, Kraków (1930), and twelve western European universities. Between 1933 and 1939 Zieliński was a member of the prestigious Polish Academy of Literature.[5]

His daughter became the wife of Prof. Vladimir Beneshevich, executed by the Soviet regime in 1938. Adrian Piotrovsky, his natural son, was arrested by the NKVD in November 1937 and executed.[6]

After the outbreak of World War II, Zieliński left Poland to live with his son in Bavaria, where he lived until he died in 1944 after completing Religions of the Ancient World, which he considered to be his magnum opus.[7]

Scholarly work

Although Zieliński was active in many areas of classical scholarship, one of the studies for which he is best known in the West is his investigation of the prose rhythm of Cicero, published in 1904, which is still often referred to today.[8] (See Clausula (rhetoric)). He was also an early mentor to Mikhail Bakhtin. Zieliński's concept of pliaska, in which logocentricism is challenged by incorporating gesture and dance into speech, is referenced in Bakhtin's communication theories that emphasize group participation in the interpretation of meaning between self and other.[9]

His work Tragodumena: De trimetri Euripidei evolutione is a primary reference work for chronology, style, and resolution within Euripides' individual plays as well as across Euripides' body of work, and employs an early narratological methodology.[10]

In 1903, he held a series of lectures to the graduates of St. Petersburg gymnasia and Realschulen about the educational significance of classical antiquity. At that time, public attacks on classical education, not only in Russia but also in central and western Europe, reached a peak, and its dominant position in the school system was shaken. Zieliński structured his lectures as defense speeches and showed with many vivid examples that classical education not only serves the idea of progress, but that its values are quite compatible with those of the natural sciences and even Darwin's theory of evolution. Based on these lectures, Zieliński's book "Our Debt to Antiquity" (in Russian: "Drevnij mir i my") has been published in 1905 and instantly became an intellectual bestseller. By 1911, it was translated into French, English, Czech and Italian, and its German translation appeared in the third edition.[11]

Works

- Cicero im Wandel der Jahrhunderte. (Leipzig 1897, 2nd ed. 1908)

- Das Clauselgesetz in Ciceros Reden. Grundzüge einer oratorischen Rhythmik (1904)

- Der Constructive Rhythmus in Ciceros Reden. Der oratorischen Rhythmik zweiter Teil (1913)

- Rzym i jego religia (1920, Polish) OCLC 119328185

- Chrześcijaństwo starożytne a filozofia rzymska (1921, Polish)

- Grecja. Budownictwo, plastyka, krajobraz (1923, Polish)

- Literatura starożytnej Grecji epoki niepodległości (1923, Polish)

- Rozwój moralności w świecie starożytnym od Homera do czasów Chrystusa (1927, Polish)

- Filheleńskie poematy Byrona (1928, Polish)

- Kleopatra (1929, Polish)

- Zieliński, Tadeusz. "Homeric psychology" (PDF).

- Zieliński, Tadeusz (1971) [1909]. Our debt to antiquity. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-1205-0. LCCN 75113317. OCLC 109089.

- Zielinski, Thaddeus (1970) [1926]. The Religion of Ancient Greece: An Outline [from original in Polish: Religya starożytnej Grecji]. Translation by Noyes, George Rapall. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 978-0-8369-5222-3. LCCN 76107838. OCLC 61443. OCLC-number for the translated edition: OCLC 753279017

References

- ^ Zieliński's identity as a Polish scholar is discussed by E. A. Rostovtsev in "The Poles in the academic corporation of St. Petersburg Imperial University (the 19th-the beginning of the 20th century." Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana 2.16 (2014):196-7, 199-200.

- ^ Kucharski Jan. (2011). Thaddaeus Zieliński in the eyes of a modern Hellenist. Scripta Classica. (Vol. 8 (2011), s. 101).

- ^ a b Sirotkina, I. (2015). "Conversion to Dionysianism: Tadeusz Zieliński and Heptachor." Models of personal conversion in Russian cultural history of the 19th and 20th centuries. 106.

- ^ Kucharski (2011): 99.

- ^ "Polska Akademia Literatury". Encyklopedia Onet.pl, Grupa Onet.pl SA. 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ Clark, Katerina (1995) Petersburg: Crucible of Cultural Revolution, Cambridge, MA: Harvard, pp. 291-2.

- ^ Kucharski (2011). 100.

- ^ Srebrny (1947 (2013)), p. 149.

- ^ Sirotkina. 109.

- ^ Kucharski (2011). 100.

- ^ Jakobidze-Gitman, Alexander (2022-09-03). "Classical education and Darwinism: Tadeusz Zielinski's attempt at reconciliation". History of Education. 51 (5): 611–630. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2021.2012602. ISSN 0046-760X. S2CID 248286187.

Further reading

- Barta, Peter I.; Larmour, David H. J.; Miller, Paul Allen (1996). Russian Literature and the Classics. Studies in Russian and European Literature. Vol. 1. Langhorne, PA: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3-7186-0605-4. OCLC 35157594.

- Srebrny, Stefan (1947 (2013)) Tadeusz Zieliński (1859-1944). (English translation of Polish original; contains photograph.)

- R. Zaborowski, "Tadeusz Zieliński (1859-1944) - sa vie et son œuvre." In: Annales du Centre Scientifique à Paris de l’Académie Polonaise des Sciences 12, 2009, pp. 207–222.

- 1859 births

- 1944 deaths

- People from Cherkasy Oblast

- Polish classical philologists

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Polish classical scholars

- Leipzig University alumni

- Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni

- University of Vienna alumni

- Academic staff of Saint Petersburg State University

- Academic staff of the University of Warsaw

- Members of the Polish Academy of Literature

- Members of the Lwów Scientific Society

- Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Corresponding Fellows of the British Academy

- Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities

- Philologists from the Russian Empire