John Francis Jackson

John Francis Jackson | |

|---|---|

Flight Lieutenant Jackson in North Africa, 1941 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Old John" |

| Born | 23 February 1908 Brisbane, Queensland |

| Died | 28 April 1942 (aged 34) Port Moresby, Territory of Papua |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service | Royal Australian Air Force |

| Years of service | 1936–1942 |

| Rank | Squadron Leader |

| Unit |

|

| Commands | No. 75 Squadron (1942) |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

| Relations | Les Jackson (brother) |

| Other work | Grazier, businessman |

John Francis Jackson, DFC (23 February 1908 – 28 April 1942) was an Australian fighter ace and squadron commander of World War II. He was credited with eight aerial victories, and led No. 75 Squadron during the Battle of Port Moresby in 1942. Born in Brisbane, he was a grazier and businessman, who also operated his own private plane, when he joined the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Reserve in 1936. Called up for active service following the outbreak of war in 1939, Jackson served with No. 23 Squadron in Australia before he was posted to the Middle East in November 1940. As a fighter pilot with No. 3 Squadron he flew Gloster Gladiators, Hawker Hurricanes and P-40 Tomahawks during the North African and Syria–Lebanon campaigns.

Jackson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and mentioned in despatches for his actions in the Middle East. Posted to the South West Pacific theatre, he was promoted to squadron leader in March 1942 and given command of No. 75 Squadron, operating P-40 Kittyhawks, at Port Moresby in Papua. Described as "rugged, simple" and "true as steel",[1] Jackson was nicknamed "Old John" in affectionate tribute to his thirty-four years. He earned praise for his leadership during the defence of Port Moresby before his death in combat on 28 April. His younger brother Les took over No. 75 Squadron, and also became a fighter ace. Jacksons International Airport, Port Moresby, is named in John Jackson's honour.

Early career

John Jackson was born on 23 February 1908 in the Brisbane suburb of New Farm, Queensland, the eldest son of businessman William Jackson and his wife Edith. Educated at Brisbane Grammar School and The Scots College, Warwick, Jackson joined the Young Australia League, with which he visited Europe.[1] After leaving school he ran a grazing property in St George.[2] By the early 1930s, he was in business as a stock and station agent, and had interests in engineering and financial concerns. He was inspired by the 1934 London to Melbourne Air Race to take up flying, and purchased a Klemm Swallow monoplane.[1][3] In 1936, he took part in the South Australian centenary air race, flying from Brisbane to Adelaide.[1] That August, he joined the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Reserve, or Citizen Air Force.[2][4] In 1937, he upgraded his aircraft to a Beechcraft Staggerwing, a type that was faster than many in the RAAF's inventory.[3]

On 17 February 1938, Jackson married Elisabeth Thompson at Christ Church, North Adelaide; the couple had a son and a daughter.[1] Following the outbreak of World War II, Jackson was called up for active duty and commissioned as a pilot officer in the RAAF on 2 October 1939.[4][5] His twenty-year-old brother Arthur, also a pilot and keen to join the Air Force, was killed in a flying accident later that month.[6][7] Two other brothers, Edward and Leslie, joined the RAAF in November.[8][9][10] John Jackson served initially with No. 23 Squadron, which operated CAC Wirraways at Archerfield, Queensland.[4][11] He was promoted to flying officer in April 1940.[12] That October, he was posted to join No. 3 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, which had been based in Egypt since August. He arrived in the Middle East in November 1940.[12][13]

Combat service

Middle East

Jackson first saw action with No. 3 Squadron in the North African campaign at the controls of a Gloster Gladiator. Soon after he arrived, he had an accident taking off that finished with the biplane on its nose.[14] Though he considered himself a "full-blown operational pilot", his experience in air-to-air gunnery was "practically nil", and he essentially learned the skills of being a fighter pilot as he went along.[3] Once the unit had converted to Hawker Hurricanes, he began to score victories in quick succession. He shot down three Junkers Ju 87s in a single sortie near Mersa Matruh on 18 February 1941, the same action in which Gordon Steege claimed three.[4][15]

On 5 April 1941, Jackson fired several bursts at a Ju 87 before his guns jammed; he then made two dummy attacks and forced the German plane to crash land in a wadi, thus claiming his fourth victory.[4][16] After converting to P-40 Tomahawks, No. 3 Squadron took part in the Syria–Lebanon campaign. Jackson became an ace on 25 June, when he destroyed a Potez 630 light bomber (possibly a misidentified LeO 451) of the Vichy French air force. He claimed a Dewoitine D.520 fighter on 10 July. The next day Jackson shared in the destruction of another D.520 with Bobby Gibbes; the pair tossed a coin to take full credit for it; Gibbes won to claim his first "kill".[2][17]

Jackson was promoted to flight lieutenant on 1 July 1941.[12] By now his younger brother Ed had been posted to No. 3 Squadron and was serving with him in Palestine.[18][19] With the campaign in Syria concluding in mid-July, the unit undertook no operations in August and personnel went on leave before returning to action in Egypt the next month.[20] The rural-bred Jackson took to the night life in Alexandria, but his stay at a first-class hotel left him bewildered as to the purpose of the room's bidet, which he eventually determined was "some feminine arrangement".[3] Peter Ewer, in Storm Over Kokoda, observed: "There was something of the patrician about John Jackson, but his well-to-do background had a distinctly Australian tinge to it. He liked a game of cards, with a bet on the outcome."[3] In Whispering Death, Mark Johnston noted that although "tall and blue-eyed", he "did not have the air of a 'boy's own' or movie star pilot", but rather was "balding, ambling and no extrovert".[18] Jackson returned to Australia in November 1941.[1][12][Note 1] He was mentioned in despatches, and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his "marked keenness and determination" during operations with No. 3 Squadron in the Middle East.[12][21] The former award was promulgated in the London Gazette on 1 January 1942 and the latter, which listed him as "John Henry Jackson", on 7 April.[22][23] The DFC was presented to Jackson's widow Elisabeth, after his death.[24]

South West Pacific

Following his return from the Middle East, Jackson was briefly an instructor at No. 1 Service Flying Training School, based at RAAF Station Point Cook, Victoria. He wrote to his wife, "I just loathe this joint. This training is a tough job and I take my hat off to the boys who have been doing it since war broke out ... every one of these instructors is longing to be sent overseas, but I doubt if they have any chance of ever getting there—they are so valuable here."[12][25] In January 1942, he was posted to No. 4 Squadron, which operated Wirraways in Canberra.[12][26]

As the Japanese advanced towards New Guinea in early 1942, the RAAF urgently established three new fighter units for Australia's northern defence, Nos. 75, 76 and 77 Squadrons.[27] Jackson was promoted to acting squadron leader and appointed commanding officer (CO) of No. 75 Squadron on 19 March, barely two weeks after the unit was formed at Townsville, Queensland.[2][28] He took over from Wing Commander Peter Jeffrey, who had led No. 3 Squadron in the Middle East and been given the task of preparing No. 75 for operations at Port Moresby, where the local Australian Army garrison was under regular attack by Japanese bombers.[27][29] Jeffrey later recalled chiding Jackson for his eagerness to return to combat despite having already done enough in the war, to which the latter replied, "What are you fighting for? King and country? Well, I'm fighting for my wife and kids and no Jap bastard's going to get them!"[30] On 21 March, Jackson led the squadron's main force to Seven Mile Aerodrome to take part in the defence of Port Moresby, a crucial early battle in the New Guinea campaign,[27] and what military aviation historian Andrew Thomas called "one of the most gallant episodes in the history of the RAAF".[28] The unit was equipped with P-40 Kittyhawks, whose long-awaited arrival had seen them irreverently dubbed "Tomorrowhawks", "Neverhawks", and "Mythhawks" by the beleaguered garrison at Moresby.[29] Jackson's age of thirty-four was considered advanced for a fighter pilot, and he was affectionately known as "Old John" to his men, one of whom was his younger brother Les, now a flight lieutenant. As CO, Jackson's leadership was to prove inspirational to his pilots, many of whom had received only nine days of training in fighter tactics, and fired their guns just once.[27][29]

On 22 March, the day after he arrived in New Guinea, Jackson took No. 75 Squadron on a dawn raid against the Japanese airfield at Lae. Rather than attacking directly from the south, he led the Kittyhawks in from the east, where they would not be expected and where the rising sun would hide their approach. Achieving the surprise he had hoped for, Jackson made two strafing passes over the airfield, ignoring standard practice that called for only one such pass to reduce the risk from anti-aircraft fire.[29][31] The Australians claimed a dozen Japanese planes destroyed on the ground and five more damaged.[2][27] They also shot down two Mitsubishi Zero fighters in the air, and lost two Kittyhawks over Lae, along with one that had crash-landed on takeoff from Moresby.[29][31] The Japanese struck back the next day, destroying two Kittyhawks at Seven Mile Aerodrome. With his losses mounting, Jackson was given permission to withdraw the squadron to Horn Island in Far North Queensland, but refused.[28][29] On 4 April, Jackson made a solo reconnaissance over Lae, after which he led another four Kittyhawks on a raid against the airfield, claiming seven enemy aircraft destroyed on the ground without loss to themselves; Japanese sources credited the Australians with only two machines destroyed, but seventeen others damaged. Two days later, Les Jackson was forced to ditch his aircraft on a coral reef, but made it to shore with the aid of a life jacket that John dropped to him, not realising at the time that the downed pilot was his younger brother.[32][33]

Jackson himself had to ditch into the sea on 10 April, when he was shot down after being surprised by three Zeros during another of his solo reconnaissance missions near Lae.[1][28] After playing dead beside his crashed plane to discourage the Japanese fighters from machine-gunning him, he swam to shore and made his way through jungle for over a week to Wau, with the help of two New Guinea natives. When he arrived back at Port Moresby in a US Douglas Dauntless on 23 April, a Japanese air raid was in progress and a bullet cut off the tip of his right index finger.[27][34] Having survived his trek through the jungle, he dismissed the wound as "a mere scratch".[35] On 27 April, Jackson met with his pilots and revealed that some senior RAAF officers had expressed dissatisfaction with the way in which No. 75 Squadron was avoiding dogfighting with the Japanese Zeros. Jackson and his men had generally eschewed such tactics owing to the Zero's superiority to the Kittyhawk in close combat. The senior officers' comments had evidently stung him, as he declared to his pilots: "Tomorrow I'm going to show you how".[36][37] According to journalist Osmar White, who saw him on the night of the 27th, Jackson's "hands and eyes were still and rock steady" but he appeared "weary in soul" and "too long in the shadows". White concluded: "He had done more than conquer fear—he had killed it".[38] The next day, Jackson led No. 75 Squadron's five remaining airworthy Kittyhawks to intercept a force of Japanese bombers and their escort. He destroyed an enemy fighter before being shot down and killed.[27][28][39][Note 2] His aircraft hit the side of a mountain and embedded itself six feet; Jackson was identified only by his size-ten boots and the revolver he habitually wore.[37][40] His final tally of aerial victories during the war was eight.[2][4][12][41]

Legacy

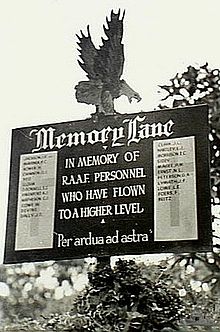

Les Jackson took over command of No. 75 Squadron the day after his brother was killed.[42] Although the squadron was no longer an effective fighting unit, it had checked Japan's attempts to overpower Port Moresby by air attack, and the town continued to function as an important Allied base.[27][43] John Jackson was survived by his wife and children, and interred in Moresby's Bomana War Cemetery.[1][44] His estate was sworn for probate at a value of £29,780 ($1,870,800 in 2011).[45][46] His name appears on panel 104 of the Commemorative Area at the Australian War Memorial (AWM), Canberra.[47] Jackson was a keen amateur film maker, and a four-minute reel of 16 mm footage that he shot in Port Moresby is held by the AWM.[48][49] Moresby's Seven Mile Aerodrome was renamed Jackson's Strip in his honour; it later became Jacksons International Airport.[1][29] In a 1989 interview, fellow No. 75 Squadron member Flight Lieutenant Albert Tucker commented, "I would say that had John F. Jackson not existed, the squadron would not have been effective in that defence role for as long as it was ... So the whole spirit of John F's leadership, and I suppose his final sacrifice, was the thing that made 75 Squadron."[50] In March 2003, the St George township erected a monument to Jackson and another local RAAF identity, Aboriginal fighter pilot Len Waters.[51]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Garrisson gives Jackson credit for destroying a Macchi C.200 fighter on 8 January 1942, but this is contradicted by his Record of Service and the Australian Dictionary of Biography, as both sources state that Jackson returned from the Middle East in November the previous year.

- ^ Gillison (1962), Newton (1996) and Garrisson (1999) express doubt as to whether responsibility for the destruction of the Japanese fighter on 28 April 1942 belonged to Jackson or to another Australian shot down in the same battle. The most recent works cited, Stephens (2001/2006), Thomas (2005), and Johnston (2011), all unequivocally ascribe this last victory to Jackson.

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jackson, John Francis at Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Newton, Australian Air Aces, p. 92

- ^ a b c d e Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, pp. 116–117

- ^ a b c d e f Garrisson, Australian Fighter Aces, pp. 140–141

- ^ Jackson, John Francis Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at World War 2 Nominal Roll Archived 5 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, p. 40

- ^ "Killed when training". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 15 December 1939. p. 10. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ "Legal notices". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 14 January 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Edward Hamilton Bell Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at World War 2 Nominal Roll. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Leslie Douglas Archived 16 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine at World War 2 Nominal Roll. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ 23 Squadron RAAF at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jackson, John Francis – Record of Service, p. 7 at National Archives of Australia. Retrieved on 12 February 2011.

- ^ Herington, Air War Against Germany and Italy, pp. 57–58 Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas, Gloster Gladiator Aces, p. 45

- ^ Thomas, Hurricane Aces 1941–45, p. 49

- ^ Thomas, Hurricane Aces 1941–45, p. 50

- ^ Thomas, Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces, p. 9

- ^ a b Johnston, Whispering Death, pp. 158–159

- ^ Item 008320 Archived 8 July 2012 at archive.today at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ Herington, Air War Against Germany and Italy, p. 95

- ^ Awarded: Mention in Despatches at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ "No. 35399". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1942. pp. 42–48.

- ^ "No. 35514". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 April 1942. p. 1556.

- ^ Recommended: Distinguished Flying Cross at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, pp. 35, 466

- ^ 4 Squadron RAAF at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 139–141

- ^ a b c d e Thomas, Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces, pp. 50–55

- ^ a b c d e f g Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 458–462

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, pp. 155–156, 470

- ^ a b Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, p. 122–127

- ^ Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, pp. 155–157

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, p. 169

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 543–546 Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Defence of Moresby Archived 27 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine at Australia's War 1939–1945 Archived 21 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2 February 2012.

- ^ Ewers, Storm Over Kokoda, pp. 187, 200

- ^ a b Johnston, Whispering Death, pp. 174–176

- ^ Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, p. 202

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, p. 452

- ^ Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, p. 204

- ^ Thomas, Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces, p. 103. Listed as seven plus one shared.

- ^ Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force, p. 547 Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Johnston, Whispering Death, p. 180

- ^ Jackson, John Francis at Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ "Airman leaves £29,780 estate". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 1 July 1943. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Pre-Decimal Inflation Calculator at Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Roll of Honour – John Francis Jackson at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 6 December 2010.

- ^ Ewer, Storm Over Kokoda, p. 152

- ^ Scenes at Port Moresby March–April 1942 taken by Squadron Leader J F Jackson DFC Archived 7 July 2012 at archive.today at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ Arthur Douglas Tucker, 75 Squadron RAAF, interviewed by Edward Stokes, p. 30 at Australian War Memorial. Retrieved on 30 January 2012.

- ^ Waters, Patrick (8 July 2005). "A tough landing". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: Queensland Newspapers. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

References

- Ewer, Peter (2011). Storm Over Kokoda: Australia's Epic Battle for the Skies of New Guinea, 1942. Miller's Point, New South Wales: Murdoch Books. ISBN 978-1-74266-095-0.

- Garrisson, A.D. (1999). Australian Fighter Aces 1914–1953. Fairbairn, Australian Capital Territory: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26540-2. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Herington, John (1954). Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series Three (Air) Volume III – Air War Against Germany and Italy 1939–1943. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3633363.

- Johnston, Mark (2011). Whispering Death: Australian Airmen in the Pacific War. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-901-3.

- Newton, Dennis (1996). Australian Air Aces. Fyshwyck, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-25-0.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Thomas, Andrew (2002). Gloster Gladiator Aces. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-289-0.

- Thomas, Andrew (2003). Hurricane Aces 1941–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-610-2.

- Thomas, Andrew (2005). Tomahawk and Kittyhawk Aces of the RAF and Commonwealth. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-083-4.

Further reading

- Wilson, David (1988). Jackson's Few: 75 Squadron RAAF, Port Moresby, March/May 1942. Chisholm, Australian Capital Territory: Self-published. ISBN 0-7316-3406-3.

- 1908 births

- 1942 deaths

- Australian military personnel killed in World War II

- Australian World War II flying aces

- Aviators killed by being shot down

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom)

- Royal Australian Air Force officers

- Royal Australian Air Force personnel of World War II

- Military personnel from Brisbane