Lisztomania

Lisztomania or Liszt fever was the intense fan frenzy directed toward Hungarian composer Franz Liszt during his performances. This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote on April 25, 1844, discussing the 1844 Parisian concert season. Lisztomania was characterized by intense levels of hysteria demonstrated by fans, akin to the treatment of celebrity musicians today – but in a time not known for such musical excitement.

Background

Franz Liszt began receiving piano lessons at the age of seven from his father Adam Liszt, a talented musician who played the piano, violin, cello, and guitar, and who knew Joseph Haydn, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and Ludwig van Beethoven personally. By age eleven, Franz Liszt was already composing music and appearing in concerts. As he grew older, Liszt continued to study and develop his expertise at playing piano.

In 1839, Liszt began an extensive tour of Europe, which he continued for the next eight years. This period was Liszt's most brilliant as a concert pianist and he received many honours and much adulation during his tours. Scholars have called these years a period of "transcendental execution" for Liszt.[1] During this period, the first reports of intense responses from Liszt's fans appeared, which became referred to as Lisztomania.

Liszt arrived in Berlin around Christmas 1841, and word of his arrival soon spread.[2] That night, a group of thirty students serenaded him with a performance of his song "Rheinweinlied".[2] He later played his first recital in Berlin on December 27, 1841, at the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin to an enthusiastic crowd. This performance would later be marked as the beginning of Lisztomania, which would sweep generally across all of Europe after 1842.[2][3]

Characteristics

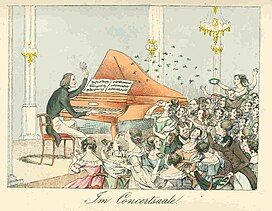

Lisztomania was characterized by a hysterical reaction to Liszt and his concerts.[2][3] Liszt's playing was reported to raise the mood of the audience to a level of mystical ecstasy.[3] Admirers of Liszt would swarm over him, fighting over his handkerchiefs and gloves.[3] Fans would wear his portrait on brooches and cameos.[2][4] Women would try to get locks of his hair, and whenever he broke a piano string, admirers would try to obtain it in order to make a bracelet.[4] Some female admirers would even carry glass phials into which they poured his coffee dregs.[2] According to one report:

Liszt once threw away an old cigar stump in the street under the watchful eyes of an infatuated lady-in-waiting, who reverently picked the offensive weed out of the gutter, had it encased in a locket and surrounded with the monogram "F.L." in diamonds, and went about her courtly duties unaware of the sickly odour it gave forth.[4]

Creation and use of the term

The writer Heinrich Heine coined the term Lisztomania to describe the outpouring of emotion that accompanied Liszt and his performances. Heine wrote a series of musical feuilletons over several different music seasons discussing the music of the day. His review of the musical season of 1844, written in Paris on April 25, 1844, is the first place where he uses the term Lisztomania:

When formerly I heard of the fainting spells which broke out in Germany and specially in Berlin, when Liszt showed himself there, I shrugged my shoulders pityingly and thought: quiet sabbatarian Germany does not wish to lose the opportunity of getting the little necessary exercise permitted it... In their case, thought I, it is a matter of the spectacle for the spectacle's sake...Thus I explained this Lisztomania, and looked on it as a sign of the politically unfree conditions existing beyond the Rhine. Yet I was mistaken, after all, and I did not notice it until last week, at the Italian Opera House, where Liszt gave his first concert...This was truly no Germanically sentimental, sentimentalizing Berlinate audience, before which Liszt played, quite alone, or rather, accompanied solely by his genius. And yet, how convulsively his mere appearance affected them! How boisterous was the applause which rang to meet him!...[W]hat acclaim it was! A veritable insanity, one unheard of in the annals of furore![5]

Musicologist Dana Gooley argues that Heine's use of the term "Lisztomania" was not used in the same way that "Beatlemania" was used to describe the intense emotion generated towards The Beatles in the 20th century. Instead, Lisztomania had much more of a medical emphasis because the term "mania" was a much stronger term in the 1840s, whereas in the 20th century "mania" could refer to something as mild as a new fashion craze. Lisztomania was considered by some a genuine contagious medical condition and critics recommended measures to immunize the public.[6]

Some critics of the day thought that Lisztomania, or "Liszt fever" as it was sometimes called, was mainly a reflection of the attitudes of Berliners and Northern Germans and that Southern German cities would not have such episodes of Lisztomania because of the difference in constitutions of the populace. As one report stated in a Munich paper in 1843:

Liszt fever, a contagion that breaks out in every city our artist visits, and which neither age nor wisdom can protect, seems to appear here only sporadically, and asphyxiating cases such as appeared so often in northern capitals need not be feared by our residents, with their strong constitutions.[6]

In 1891, American poet Nathan Haskell Dole used the term in a relatively neutral context, to describe pianists' momentary fixation on Liszt's compositions:

It is therefore not an uncommon phenomenon to see pianists outgrowing their Liszt enthusiasms and to look back upon their "Lisztomania" as only a phase of development, of which they are not ashamed, but rather proud.[7]

Causes

There was no known cause for Lisztomania, but there were attempts to explain the condition. Heine tried to explain the cause of Lisztomania in the same letter in which he first used the term. In that letter he wrote:

What is the reason of this phenomenon? The solution of this question belongs to the domain of pathology rather than that of aesthetics. A physician, whose specialty is female diseases, and whom I asked to explain the magic our Liszt exerted upon the public, smiled in the strangest manner, and at the same time said all sorts of things about magnetism, galvanism, electricity, of the contagion of the close hall filled with countless wax lights and several hundred perfumed and perspiring human beings, of historical epilepsy, of the phenomenon of tickling, of musical cantherides, and other scabrous things, which, I believe have reference to the mysteries of the bona dea. Perhaps the solution of the question is not buried in such adventurous depths, but floats on a very prosaic surface. It seems to me at times that all this sorcery may be explained by the fact that no one on earth knows so well how to organize his successes, or rather their mise en scene, as our Franz Liszt.[5]

Dana Gooley argues that different people attributed the cause of Lisztomania in Berlin audiences in a different manner based on their political leanings at the time; furthermore, those who had a progressive view of affairs thought that the outpouring of emotions by Berlin audiences was largely a side effect of the repressive and censorious state and that the enthusiasm for Liszt was "compensatory, an illusory substitute for the lack of agency and public participation among Berliners". The opposing positive view of Lisztomania was that it was a response to Liszt's great benevolence and charity.[6] This view was explained as follows:

Friedrich Wilhelm IV's optimistic and popular political rhetoric, with its promise of liberal social reforms, predisposed the Berlin public to appreciate Liszt's various gestures in support of charitable, humanitarian causes, as they saw themselves and their monarch echoes in Liszt's benevolence. But significantly, they found evidence of it not solely in his donations. His personal openness, his behavior towards audiences, and his performing style all became emblems of "charity" as well.[6]

One contributing factor to Lisztomania is also assumed to have been that Liszt, in his younger years, was known to be a handsome man.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Keller, Johanna (14 January 2001). "In Search of a Liszt to Be Loved". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Walker 1987, p. 371

- ^ a b c d Walker 1987, p. 289

- ^ a b c Walker 1987, p. 372

- ^ a b Sonneck, Oscar George Theodore (1922). "Henrick Heine's Musical Feuilletons". The Musical Quarterly. 8 (3): 457–458. doi:10.1093/mq/viii.3.435. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d Gooley, Dana Andrew (2004). The Virtuoso Liszt. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–235. ISBN 0-521-83443-0.

- ^ Dole, Nathan Haskell (1891). A Score of Famous Composers. T. Y. Crowell & Company.

- ^ BBC Culture – "Forget The Beatles – Liszt was music's first 'superstar.'" August 17, 2016. Read May 4, 2019.

Sources

- Walker, Alan (1987). Franz Liszt, The Virtuoso Years (1811–1847) (revised ed.). Cornell University Press.

External links

- Lisztomania 2011 Festival, Burgenland, Austria

- Lisztomania 2011, festival of seven concerts at New England Conservatory, Boston

- "How Franz Liszt Became The World's First Rock Star", NPR story about Lisztomania