Data type

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

In computer science and computer programming, a data type (or simply type) is a collection or grouping of data values, usually specified by a set of possible values, a set of allowed operations on these values, and/or a representation of these values as machine types.[1] A data type specification in a program constrains the possible values that an expression, such as a variable or a function call, might take. On literal data, it tells the compiler or interpreter how the programmer intends to use the data. Most programming languages support basic data types of integer numbers (of varying sizes), floating-point numbers (which approximate real numbers), characters and Booleans.[2][3]

Concept

A data type may be specified for many reasons: similarity, convenience, or to focus the attention. It is frequently a matter of good organization that aids the understanding of complex definitions. Almost all programming languages explicitly include the notion of data type, though the possible data types are often restricted by considerations of simplicity, computability, or regularity. An explicit data type declaration typically allows the compiler to choose an efficient machine representation, but the conceptual organization offered by data types should not be discounted.[4]

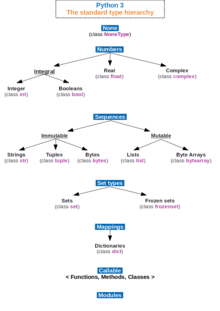

Different languages may use different data types or similar types with different semantics. For example, in the Python programming language, int represents an arbitrary-precision integer which has the traditional numeric operations such as addition, subtraction, and multiplication. However, in the Java programming language, the type int represents the set of 32-bit integers ranging in value from −2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647, with arithmetic operations that wrap on overflow. In Rust this 32-bit integer type is denoted i32 and panics on overflow in debug mode.[5]

Most programming languages also allow the programmer to define additional data types, usually by combining multiple elements of other types and defining the valid operations of the new data type. For example, a programmer might create a new data type named "complex number" that would include real and imaginary parts, or a color data type represented by three bytes denoting the amounts each of red, green, and blue, and a string representing the color's name.

Data types are used within type systems, which offer various ways of defining, implementing, and using them. In a type system, a data type represents a constraint placed upon the interpretation of data, describing representation, interpretation and structure of values or objects stored in computer memory. The type system uses data type information to check correctness of computer programs that access or manipulate the data. A compiler may use the static type of a value to optimize the storage it needs and the choice of algorithms for operations on the value. In many C compilers the float data type, for example, is represented in 32 bits, in accord with the IEEE specification for single-precision floating point numbers. They will thus use floating-point-specific microprocessor operations on those values (floating-point addition, multiplication, etc.).

Most data types in statistics have comparable types in computer programming, and vice versa, as shown in the following table:

| Statistics | Programming |

|---|---|

| real-valued (interval scale) | floating-point |

| real-valued (ratio scale) | |

| count data (usually non-negative) | integer |

| binary data | Boolean |

| categorical data | enumerated type |

| random vector | list or array |

| random matrix | two-dimensional array |

| random tree | tree |

Definition

Parnas, Shore & Weiss (1976) identified five definitions of a "type" that were used—sometimes implicitly—in the literature:

- Syntactic

- A type is a purely syntactic label associated with a variable when it is declared. Although useful for advanced type systems such as substructural type systems, such definitions provide no intuitive meaning of the types.

- Representation

- A type is defined in terms of a composition of more primitive types—often machine types.

- Representation and behaviour

- A type is defined as its representation and a set of operators manipulating these representations.

- Value space

- A type is a set of possible values which a variable can possess. Such definitions make it possible to speak about (disjoint) unions or Cartesian products of types.

- Value space and behaviour

- A type is a set of values which a variable can possess and a set of functions that one can apply to these values.

The definition in terms of a representation was often done in imperative languages such as ALGOL and Pascal, while the definition in terms of a value space and behaviour was used in higher-level languages such as Simula and CLU. Types including behavior align more closely with object-oriented models, whereas a structured programming model would tend to not include code, and are called plain old data structures.

Classification

Data types may be categorized according to several factors:

- Primitive data types or built-in data types are types that are built-in to a language implementation. User-defined data types are non-primitive types. For example, Java's numeric types are primitive, while classes are user-defined.

- A value of an atomic type is a single data item that cannot be broken into component parts. A value of a composite type or aggregate type is a collection of data items that can be accessed individually.[6] For example, an integer is generally considered atomic, although it consists of a sequence of bits, while an array of integers is certainly composite.

- Basic data types or fundamental data types are defined axiomatically from fundamental notions or by enumeration of their elements. Generated data types or derived data types are specified, and partly defined, in terms of other data types. All basic types are atomic.[7] For example, integers are a basic type defined in mathematics, while an array of integers is the result of applying an array type generator to the integer type.

The terminology varies - in the literature, primitive, built-in, basic, atomic, and fundamental may be used interchangeably.[8]

Examples

Machine data types

All data in computers based on digital electronics is represented as bits (alternatives 0 and 1) on the lowest level. The smallest addressable unit of data is usually a group of bits called a byte (usually an octet, which is 8 bits). The unit processed by machine code instructions is called a word (as of 2011[update], typically 32 or 64 bits).

Machine data types expose or make available fine-grained control over hardware, but this can also expose implementation details that make code less portable. Hence machine types are mainly used in systems programming or low-level programming languages. In higher-level languages most data types are abstracted in that they do not have a language-defined machine representation. The C programming language, for instance, supplies types such as booleans, integers, floating-point numbers, etc., but the precise bit representations of these types are implementation-defined. The only C type with a precise machine representation is the char type that represents a byte.[9]

Boolean type

The Boolean type represents the values true and false. Although only two values are possible, they are more often represented as a word rather as a single bit as it requires more machine instructions to store and retrieve an individual bit. Many programming languages do not have an explicit Boolean type, instead using an integer type and interpreting (for instance) 0 as false and other values as true. Boolean data refers to the logical structure of how the language is interpreted to the machine language. In this case a Boolean 0 refers to the logic False. True is always a non zero, especially a one which is known as Boolean 1.

Numeric types

Almost all programming languages supply one or more integer data types. They may either supply a small number of predefined subtypes restricted to certain ranges (such as short and long and their corresponding unsigned variants in C/C++); or allow users to freely define subranges such as 1..12 (e.g. Pascal/Ada). If a corresponding native type does not exist on the target platform, the compiler will break them down into code using types that do exist. For instance, if a 32-bit integer is requested on a 16 bit platform, the compiler will tacitly treat it as an array of two 16 bit integers.

Floating point data types represent certain fractional values (rational numbers, mathematically). Although they have predefined limits on both their maximum values and their precision, they are sometimes misleadingly called reals (evocative of mathematical real numbers). They are typically stored internally in the form a × 2b (where a and b are integers), but displayed in familiar decimal form.

Fixed point data types are convenient for representing monetary values. They are often implemented internally as integers, leading to predefined limits.

For independence from architecture details, a Bignum or arbitrary precision numeric type might be supplied. This represents an integer or rational to a precision limited only by the available memory and computational resources on the system. Bignum implementations of arithmetic operations on machine-sized values are significantly slower than the corresponding machine operations.[10]

Enumerations

The enumerated type has distinct values, which can be compared and assigned, but which do not necessarily have any particular concrete representation in the computer's memory; compilers and interpreters can represent them arbitrarily. For example, the four suits in a deck of playing cards may be four enumerators named CLUB, DIAMOND, HEART, SPADE, belonging to an enumerated type named suit. If a variable V is declared having suit as its data type, one can assign any of those four values to it. Some implementations allow programmers to assign integer values to the enumeration values, or even treat them as type-equivalent to integers.

String and text types

Strings are a sequence of characters used to store words or plain text, most often textual markup languages representing formatted text. Characters may be a letter of some alphabet, a digit, a blank space, a punctuation mark, etc. Characters are drawn from a character set such as ASCII. Character and string types can have different subtypes according to the character encoding. The original 7-bit wide ASCII was found to be limited, and superseded by 8, 16 and 32-bit sets, which can encode a wide variety of non-Latin alphabets (such as Hebrew and Chinese) and other symbols. Strings may be of either variable length or fixed length, and some programming languages have both types. They may also be subtyped by their maximum size.

Since most character sets include the digits, it is possible to have a numeric string, such as "1234". These numeric strings are usually considered distinct from numeric values such as 1234, although some languages automatically convert between them.

Union types

A union type definition will specify which of a number of permitted subtypes may be stored in its instances, e.g. "float or long integer". In contrast with a record, which could be defined to contain a float and an integer, a union may only contain one subtype at a time.

A tagged union (also called a variant, variant record, discriminated union, or disjoint union) contains an additional field indicating its current type for enhanced type safety.

Algebraic data types

An algebraic data type (ADT) is a possibly recursive sum type of product types. A value of an ADT consists of a constructor tag together with zero or more field values, with the number and type of the field values fixed by the constructor. The set of all possible values of an ADT is the set-theoretic disjoint union (sum), of the sets of all possible values of its variants (product of fields). Values of algebraic types are analyzed with pattern matching, which identifies a value's constructor and extracts the fields it contains.

If there is only one constructor, then the ADT corresponds to a product type similar to a tuple or record. A constructor with no fields corresponds to the empty product (unit type). If all constructors have no fields then the ADT corresponds to an enumerated type.

One common ADT is the option type, defined in Haskell as data Maybe a = Nothing | Just a.[11]

Data structures

Some types are very useful for storing and retrieving data and are called data structures. Common data structures include:

- An array (also called vector, list, or sequence) stores a number of elements and provides random access to individual elements. The elements of an array are typically (but not in all contexts) required to be of the same type. Arrays may be fixed-length or expandable. Indices into an array are typically required to be integers (if not, one may stress this relaxation by speaking about an associative array) from a specific range (if not all indices in that range correspond to elements, it may be a sparse array).

- Record (also called tuple or struct) Records are among the simplest data structures. A record is a value that contains other values, typically in fixed number and sequence and typically indexed by names. The elements of records are usually called fields or members.

- An object contains a number of data fields, like a record, and also offers a number of subroutines for accessing or modifying them, called methods.

- the singly linked list, which can be used to implement a queue and is defined in Haskell as the ADT

data List a = Nil | Cons a (List a), and - the binary tree, which allows fast searching, and can be defined in Haskell as the ADT

data BTree a = Nil | Node (BTree a) a (BTree a)[12]

Abstract data types

An abstract data type is a data type that does not specify the concrete representation of the data. Instead, a formal specification based on the data type's operations is used to describe it. Any implementation of a specification must fulfill the rules given. For example, a stack has push/pop operations that follow a Last-In-First-Out rule, and can be concretely implemented using either a list or an array. Another example is a set which stores values, without any particular order, and no repeated values. Values themselves are not retrieved from sets, rather one tests a value for membership to obtain a boolean "in" or "not in".

Abstract data types are used in formal semantics and program verification and, less strictly, in design. Beyond verification, a specification might immediately be turned into an implementation. The OBJ family of programming languages for instance bases on this option using equations for specification and rewriting to run them. Algebraic specification[13] was an important subject of research in CS around 1980 and almost a synonym for abstract data types at that time. It has a mathematical foundation in universal algebra.[14] The specification language can be made more expressive by allowing other formulas than only equations.

A more involved example is the Boom hierarchy of the binary tree, list, bag and set abstract data types.[15] All these data types can be declared by three operations: null, which constructs the empty container, single, which constructs a container from a single element and append, which combines two containers of the same type. The complete specification for the four data types can then be given by successively adding the following rules over these operations:

| - null is the left and right neutral for a tree: | append(null,A) = A, append(A,null) = A. |

| - lists add that append is associative: | append(append(A,B),C) = append(A,append(B,C)). |

| - bags add commutativity: | append(B,A) = append(A,B). |

| - finally, sets are also idempotent: | append(A,A) = A. |

Access to the data can be specified by pattern-matching over the three operations, e.g. a member function for these containers by:

| - member(X,single(Y)) = eq(X,Y) |

| - member(X,null) = false |

| - member(X,append(A,B)) = or(member(X,A), member(X,B)) |

Care must be taken to ensure that the function is invariant under the relevant rules for the data type. Within each of the equivalence classes implied by the chosen subset of equations, it has to yield the same result for all of its members.

Pointers and references

The main non-composite, derived type is the pointer, a data type whose value refers directly to (or "points to") another value stored elsewhere in the computer memory using its address. It is a primitive kind of reference. (In everyday terms, a page number in a book could be considered a piece of data that refers to another one). Pointers are often stored in a format similar to an integer; however, attempting to dereference or "look up" a pointer whose value was never a valid memory address would cause a program to crash. To ameliorate this potential problem, pointers are considered a separate type to the type of data they point to, even if the underlying representation is the same.

Function types

Functional programming languages treat functions as a distinct datatype and allow values of this type to be stored in variables and passed to functions. Some multi-paradigm languages such as JavaScript also have mechanisms for treating functions as data.[16] Most contemporary type systems go beyond JavaScript's simple type "function object" and have a family of function types differentiated by argument and return types, such as the type Int -> Bool denoting functions taking an integer and returning a boolean. In C, a function is not a first-class data type but function pointers can be manipulated by the program. Java and C++ originally did not have function values but have added them in C++11 and Java 8.

Type constructors

A type constructor builds new types from old ones, and can be thought of as an operator taking zero or more types as arguments and producing a type. Product types, function types, power types and list types can be made into type constructors.

Quantified types

Universally-quantified and existentially-quantified types are based on predicate logic. Universal quantification is written as or forall x. f x and is the intersection over all types x of the body f x, i.e. the value is of type f x for every x. Existential quantification written as or exists x. f x and is the union over all types x of the body f x, i.e. the value is of type f x for some x.

In Haskell, universal quantification is commonly used, but existential types must be encoded by transforming exists a. f a to forall r. (forall a. f a -> r) -> r or a similar type.

Refinement types

A refinement type is a type endowed with a predicate which is assumed to hold for any element of the refined type. For instance, the type of natural numbers greater than 5 may be written as

Dependent types

A dependent type is a type whose definition depends on a value. Two common examples of dependent types are dependent functions and dependent pairs. The return type of a dependent function may depend on the value (not just type) of one of its arguments. A dependent pair may have a second value of which the type depends on the first value.

Intersection types

An intersection type is a type containing those values that are members of two specified types. For example, in Java the class Boolean implements both the Serializable and the Comparable interfaces. Therefore, an object of type Boolean is a member of the type Serializable & Comparable. Considering types as sets of values, the intersection type is the set-theoretic intersection of and . It is also possible to define a dependent intersection type, denoted , where the type may depend on the term variable .[17]

Meta types

Some programming languages represent the type information as data, enabling type introspection and reflection. In contrast, higher order type systems, while allowing types to be constructed from other types and passed to functions as values, typically avoid basing computational decisions on them.[citation needed]

Convenience types

For convenience, high-level languages and databases may supply ready-made "real world" data types, for instance times, dates, and monetary values (currency).[18][19] These may be built-in to the language or implemented as composite types in a library.[20]

See also

- C data types

- Data dictionary

- Functional programming

- Kind

- Type (model theory)

- Type theory for the mathematical models of types

- Type system for different choices in programming language typing

- Type conversion

- ISO/IEC 11404, General Purpose Datatypes

References

- ^ Parnas, Shore & Weiss 1976.

- ^ type at the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing

- ^ Shaffer, C. A. (2011). Data Structures & Algorithm Analysis in C++ (3rd ed.). Mineola, NY: Dover. 1.2. ISBN 978-0-486-48582-9.

- ^ Scott, Dana (September 1976). "Data Types as Lattices". SIAM Journal on Computing. 5 (3): 540–541. doi:10.1137/0205037.

- ^ "Rust RFCs - Integer Overflow". The Rust Programming Language. 12 August 2022.

- ^ Dale, Nell B.; Weems, Chip; Headington, Mark R. (1998). Programming in C++. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-7637-0537-4.

- ^ ISO/IEC 11404, 6.4

- ^ BHATNAGAR, SEEMA (19 August 2008). TEXTBOOK OF COMPUTER SCIENCE FOR CLASS XI. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 182. ISBN 978-81-203-2993-5.

- ^ "SC22/WG14 N2176" (PDF). Wayback Machine. Section 6.2.6.2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2018.

Which of [sign and magnitude, two's complement, one's complement] applies is implementation-defined

- ^ "Integer benchmarks — mp++ 0.27 documentation". bluescarni.github.io.

- ^ "6 Predefined Types and Classes". www.haskell.org. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- ^ Suresh, S P. "Programming in Haskell: Lecture 22" (PDF). Chennai Mathematical Institute. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Ehrig, H. (1985). Fundamentals of Algebraic Specification 1 - Equations and Initial Semantics. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-13718-1.

- ^ Wechler, Wolfgang (1992). Universal Algebra for Computer Scientists. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-54280-9.

- ^ Bunkenburg, Alexander (1994). "The Boom Hierarchy". Functional Programming, Glasgow 1993. Workshops in Computing: 1–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.49.3252. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-3236-3_1. ISBN 978-3-540-19879-6.

- ^ Flanagan, David (1997). "6.2 Functions as Data Types". JavaScript: the definitive guide (2nd ed.). Cambridge: O'Reilly & Associates. ISBN 9781565922341.

- ^ Kopylov, Alexei (2003). "Dependent intersection: A new way of defining records in type theory". 18th IEEE Symposium on Logic in Computer Science. LICS 2003. IEEE Computer Society. pp. 86–95. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.89.4223. doi:10.1109/LICS.2003.1210048.

- ^ West, Randolph (27 May 2020). "How SQL Server stores data types: money". Born SQL. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

Some time ago I described MONEY as a "convenience" data type which is effectively the same as DECIMAL(19,4), [...]

- ^ "Introduction to data types and field properties". support.microsoft.com. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Wickham, Hadley (2017). "16 Dates and times". R for data science: import, tidy, transform, visualize, and model data. Sebastopol, CA. ISBN 978-1491910399. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Parnas, David L.; Shore, John E.; Weiss, David (1976). "Abstract types defined as classes of variables". Proceedings of the 1976 conference on Data : Abstraction, definition and structure -. pp. 149–154. doi:10.1145/800237.807133. S2CID 14448258.

- Cardelli, Luca; Wegner, Peter (December 1985). "On Understanding Types, Data Abstraction, and Polymorphism" (PDF). ACM Computing Surveys. 17 (4): 471–523. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.117.695. doi:10.1145/6041.6042. ISSN 0360-0300. S2CID 2921816. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-03.

- Cleaveland, J. Craig (1986). An Introduction to Data Types. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0201119404.

External links

Media related to Data types at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Data types at Wikimedia Commons