Zamilon virophage

| Mimivirus-dependent virus Zamilon | |

|---|---|

| |

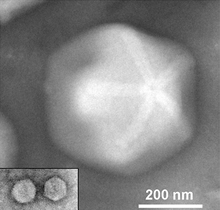

| Two Zamilon virophages (inset) to scale with their associated giant virus Megavirus [1] | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Preplasmiviricota |

| Class: | Maveriviricetes |

| Order: | Priklausovirales |

| Family: | Lavidaviridae |

| Genus: | Sputnikvirus |

| Species: | Mimivirus-dependent virus Zamilon

|

Mimivirus-dependent virus Zamilon, or Zamilon, is a virophage, a group of small DNA viruses that infect protists and require a helper virus to replicate; they are a type of satellite virus.[2] Discovered in 2013 in Tunisia, infecting Acanthamoeba polyphaga amoebae, Zamilon most closely resembles Sputnik, the first virophage to be discovered. The name is Arabic for "the neighbour".[3] Its spherical particle is 50–60 nm in diameter, and contains a circular double-stranded DNA genome of around 17 kb, which is predicted to encode 20 polypeptides. A related strain, Zamilon 2, has been identified in North America.

All known virophages are associated with helpers in the giant DNA virus family Mimiviridae. Zamilon is restricted in its range of helper viruses; it can be supported by viruses from Mimivirus-like Mimiviridae lineages B and C, but not from lineage A. This appears to be a consequence of a rudimentary immune system of the helper virus, termed MIMIVIRE (mimivirus virophage resistance element), akin to the CRISPR-Cas pathway.[4] Unlike the Sputnik virophage, Zamilon does not appear to impair the replication of its helper virus.

Discovery and related virophages

Zamilon was discovered in 2013, in Acanthamoeba polyphaga amoebae co-infected with the giant virus Mont1, isolated from a Tunisian soil sample.[2][3][5] As of 2015, Zamilon is one of three virophages to have been isolated physically, the others being Sputnik and Mavirus; several other virophage DNAs have been discovered using metagenomics but have not been characterised physically.[2][6] A related strain, named Zamilon 2, was discovered by metagenomic analysis of a North American poplar wood chip bioreactor in 2015.[7] Another virophage, Rio Negro, is also closely related to Sputnik.[2]

Taxonomy

Zamilon virophage has been classified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses into the species Mimivirus-dependent virus Zamilon within the genus Sputnikvirus in the family Lavidaviridae.[2]

Virology

A Zamilon virion is spherical with a diameter of 50–60 nm, and is similar in appearance to those of Sputnik and Mavirus.[3] Its circular double-stranded DNA genome is 17,276 base pairs in length.[2][3] Virophages typically have particles whose diameter is in the range 40–80 nm, with genomes in the range 17–30 kb.[2] The virophage most closely related to Zamilon is Sputnik, with which it shares 76% sequence identity, although part of the Zamilon sequence is reversed compared with Sputnik.[2][3] Zamilon's DNA is rich in adenine and thymine bases; the proportion of guanine and cytosine bases is 29.7%.[3]

Open reading frames

The Zamilon genome is predicted to contain 20 open reading frames (ORFs), of between 222 bases and 2337 bases in length. Of the 20 predicted products, 15 are similar to those of Sputnik, and three are similar to Mimiviridae: two to Megavirus chilensis and another to the transpoviron of Moumouvirus monve. One Zamilon ORF additionally shows some similarity to Mavirus, and another to Organic Lake virophage and a Phaeocystis globosa virophage, which are both associated with algae rather than amoebae. The remaining two predicted products show limited similarity to other known proteins. Putative functions of the products include transposase, helicase, integrase, cysteine protease, DNA primase–polymerase and DNA-packaging ATPase enzymes, major and minor capsid proteins, a structural protein and a collagen-like protein.[3] ORF6 is very similar to the Sputnik major capsid protein, which has a double "jelly-roll" fold.[3][8]

| ORF[a] | Predicted size (amino acids) |

Related product | Similarity (%) |

Predicted function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 111 | none | – | – |

| 2 | 73 | none | – | – |

| 3 | 135 | Megavirus chilensis mg3 gene product | 67 | – |

| 4 | 221 | Sputnik virophage 2 putative IS3 family transposase A protein | 40 | putative transposase |

| 5 | 376 | Sputnik virophage 2 minor virion protein | 66 | minor virion protein |

| 6 | 609 | Sputnik virophage capsid protein V20 | 86 | capsid protein |

| 7 | 442 | Sputnik virophage V21 | 70 | – |

| 8 | 81 | Moumouvirus monve hypothetical protein tv_L8 | 72 | – |

| 9 | 778 | Sputnik virophage V13 | 67 | putative helicase |

| 10 | 168 | Sputnik virophage V11 | 53 | – |

| 11 | 247 | Sputnik virophage V10 | 58 | putative integrase |

| 12 | 175 | Sputnik virophage V9 | 77 | – |

| 13 | 184 | Sputnik virophage V8 | 71 | structural protein |

| 14 | 241 | Sputnik virophage V7 | 80 | – |

| 15 | 305 | Sputnik virophage V6 | 75 | collagen-like protein |

| 16 | 121 | Sputnik virophage V5 | 59 | – |

| 17 | 133 | Sputnik virophage V4 | 55 | – |

| 18 | 245 | Sputnik virophage V3 | 81 | DNA-packaging ATPase |

| 19 | 147 | Megavirus chilensis mg664 gene product | 50 | – |

| 20 | 147 | Sputnik virophage V1 | 60 | – |

Life cycle and helper virus

Like all other virophages, Zamilon replicates in the cytoplasm, within the virus factory of its helper, which acts as its host.[3] Zamilon was first isolated in association with Mont1, a Mimivirus-like Mimiviridae classified in lineage C by its polymerase B gene sequence. The virophage has subsequently been shown to be capable of replicating in association with Moumouvirus and Monve, two Mimiviridae from lineage B, as well as with Terra1 and Courdo11 from lineage C; however, it cannot replicate in association with either Mimivirus or Mamavirus, classified as lineage A.[3][9] This is unlike Sputnik, which can replicate in association with any Mimivirus-like member of Mimiviridae.[3]

Zamilon does not appear to inhibit the ability of its helper virus to replicate significantly, nor to lyse its host amoebae cells. Although the helper virus formed a high proportion of abnormal virions in the presence of Zamilon, these were also observed at a comparable level in the virophage's absence.[3] This is again unlike Sputnik, which reduces its helper virus's infectivity, inhibits its lysis of amoeba, and is associated with the generation of an increased proportion of abnormal Mimiviridae virions.[2][3] Bernard La Scola and colleagues, who isolated both Sputnik and Zamilon, state that, if confirmed, this "would question the concept of virophage", which has been considered to be differentiated from most other satellite viruses in having a deleterious effect on its helper virus.[3]

-

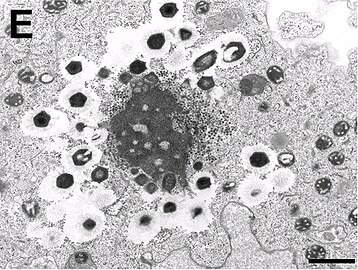

Electron micrograph of a virus factory in an amoeba co-infected with Mimivirus-dependent virus Zamilon (small particles) and Mont1. Arrows show abnormal Mont1 particles (scale bar: 0.1 μm)

-

Electron micrograph of virus factory in an amoeba co-infected with Zamilon and Mont1 (scale bar: 0.1 μm)

References

- ^ Duponchel, S. and Fischer, M.G. (2019) "Viva lavidaviruses! Five features of virophages that parasitize giant DNA viruses". PLoS pathogens, 15(3). doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1007592.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Krupovic M, Kuhn JH, Fischer MG (2016), "A classification system for virophages and satellite viruses", Archives of Virology, 161 (1): 233–47, doi:10.1007/s00705-015-2622-9, PMID 26446887

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gaia M, Benamar S, Boughalmi M, Pagnier I, Croce O, Colson P, Raoult D, La Scola B (2014), "Zamilon, a Novel Virophage with Mimiviridae Host Specificity", PLOS One, 9 (4): e94923, Bibcode:2014PLoSO...994923G, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094923, PMC 3991649, PMID 24747414

- ^ Levasseur A, Bekliz M, Chabrière E, Pontarotti P, La Scola B, Raoult D (2016), "MIMIVIRE is a defence system in mimivirus that confers resistance to virophage", Nature, 531 (7593): 249–252, Bibcode:2016Natur.531..249L, doi:10.1038/nature17146, PMID 26934229, S2CID 4382855

- ^ Boughalmi M, Saadi H, Pagnier I, Colson P, Fournous G, Raoult D, La Scola B (2013), "High-throughput isolation of giant viruses of the Mimiviridae and Marseilleviridae families in the Tunisian environment", Environmental Microbiology, 15 (7): 2000–7, doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12068, PMID 23298151

- ^ Yutin N, Kapitonov VV, Koonin EV (2015), "A new family of hybrid virophages from an animal gut metagenome", Biology Direct, 10: 19, doi:10.1186/s13062-015-0054-9, PMC 4409740, PMID 25909276

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bekliz M, Verneau J, Benamar S, Raoult D, La Scola B, Colson P (2015), "A New Zamilon-like Virophage Partial Genome Assembled from a Bioreactor Metagenome", Frontiers in Microbiology, 6: 1308, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01308, PMC 4661282, PMID 26640459

- ^ Zhang X, Sun S, Xiang Y, Wong J, Klose T, Raoult D, Rossmann MG (2012), "Structure of Sputnik, a virophage, at 3.5-Å resolution", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109 (45): 18431–36, Bibcode:2012PNAS..10918431Z, doi:10.1073/pnas.1211702109, PMC 3494952, PMID 23091035

- ^ Aherfia S, La Scola B, Pagniera I, Raoult D, Colson P (2014), "The expanding family Marseilleviridae", Virology, 466–467: 27–37, doi:10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.014, PMID 25104553