Talagunda pillar inscription

Talagunda pillar inscription

Talagunda | |

|---|---|

village | |

455–470 CE Talagunda Pillar Sanskrit inscription, Pranavesvara temple ruins, Karnataka Talagunda pillar | |

| Coordinates: 14°25′22″N 75°15′13″E / 14.422754899747806°N 75.25356570997508°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Karnataka |

| District | Shimoga District |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Kannada |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 577 450 |

| Telephone code | 08187 |

| Vehicle registration | KA-14 |

The Tālagunda pillar inscription of Kakusthavarman is an epigraphic record in Sanskrit found in the ruined Pranavalingeshwara temple northwest of village Talagunda, Karnataka, India.[1] It is engraved on hard grey granite and dated to between 455 and 470 CE.[1][2] It gives an account of a Kadamba dynasty and the times of king Śāntivarma in northwest Karnataka.

Location

The pillar is located in front of the ruined and partially restored Prāṇaveśvara Śiva temple – also called Pranavalingeshwara temple – in Talagunda village, Shikaripur taluk in Shimoga district, Karnataka, India.[2] It is close to the Karnataka State Highway 1, about 90 kilometers west of Davanagere and 80 kilometers northwest of Shivamogga city.

Publication

The inscription was discovered in 1894 by B. L. Rice, then Director of Archaeological Researches in Mysore and a celebrated pioneer of historical studies in Karṇāṭaka. He gave a photograph to the colonial era Indologist Buhler, who published it 1895. The inscription's historical significance caught the attention of the epigraphist Fleet who published some notes.[2]

Rice published a translation of the inscription in 1902, in volume 7 of Epigraphia Carnatica.[3] A more accurate reading of the inscription and more exhaustive interpretation and translation was published by the Sanskrit scholar Kielhorn in Epigraphia Indica in 1906.[2] Sircar included the record in his Select Inscriptions.[4] More recent collections have included the inscription again, notably those by B. R. Gopal,[5] and G. S. Gai.[6]

Description

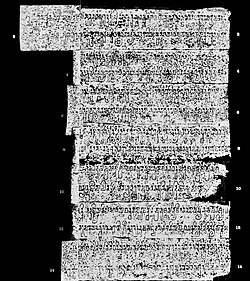

The inscription is engraved into a hard grey granite pillar and installed in front of a 5th-century Shiva temple. However, the temple was largely destroyed and only ruins had survived when the pillar was rediscovered in late 19th-century. The pillar is 1.635 metres (5.36 ft) high with a 0.4 metres (1.3 ft) square top.[2] It is octagonal shaft that slightly tapers and narrows as it goes up. The width of the octagonal face is 0.178 metres (0.58 ft). The inscription is on all faces, but on 7 of the 8 faces, it consists of two vertical lines that start at the bottom of the pillar. On the eighth face, there is just one short line.[2] The inscription begins with Siddham like numerous early inscriptions in India, and it invokes "Namo Shivaya".[2]

The language is excellent classical Sanskrit (Paninian Sanskrit). The script is Kannada and the font is floral box-type.[1][2]

The inscription consists of 34 poetic verses that respect the chanda rules of Sanskrit. However, it uses a mix of meters such as Pushpitagra, Indravajra, Vasantatilaka, Prachita and others. Each verse has four padas. The inscription's first 24 verses are the earliest known use of matrasamaka meter. These features suggest that the author(s) of this inscription had an intimate expertise in classical Sanskrit and Vedic literature on prosody.[2]

Translations

The earliest translation of the inscription was published in a prose form by B.L. Rice.[3] A more detailed verse by verse translation was published later by F. Kielhorn.

- B.L. Rice 1902 translation (Epigrahica Carnatica, Volume 7 Part 1, Inscription 176)

Early prose form translation

|

|---|

|

Siddham. Obeisance to Siva. Victorious is the one form filled with all the combination of vedas, the eternal, Sthanu, adorned with shining matted hair intermingled with the light of the moon. After him the Brahmins, the most excellent of the twice-born, reciters of the Sama, Rig and Yajur vedas ; whose favour daily preserves the three worlds from the fear of sin. By degrees the equal of Surendra in wealth, was the king Kakusthavarmma, of great intellect, the Kadamba Senani (or god of war), the moon in the sky of a great race (brihad-anvaya). Now there was a family of the twice-born, the circle of the moonlight of whose virtues was widely extended, born in the gotra of the Haritipatra, the chief rishi Manavya of the path of three rishis. Their hair was wet with constant bathing in the holy water of the final ablutions after many kinds of sacrifices, perfect (masters of learning) in having performed the avagaha (bath on completion of vedic study), maintaining the (sacred) fire according to precept, and drinking soma juice. The interior of their house resounded with the six modes of reading (the sacred books), preceded by the syllable Om, and they grew fat on full Chatturmasya homas, sacrificial animals and the funeral offerings at the parvas. Their house was the daily resort of guests, and they performed the bathing and daily rites at the three times. They had one Kadamba tree, sprung up and blossoming in the space near their house from tending which they acquired the name and qualities of that tree, and it was the general designation of that group of Brahmins. In the Kadamba family thus descended, was an illustrious one, an eminent twice-born, named MayuraSarma, adorned with sacred learning, good disposition, purity and other such (virtues). He set out for the city of the Pallava kings, together with his guru Virasarmma, and desiring to be proficient in pravachana, entered into all religious centres (ghatika) and (so) became a quick (or ready) debater (or disputant). There, being enraged by a sharp quarrel connected with the Pallava horse (or stables), he said — In this Kali-yuga, Oh! shame ; through the Kshatras Brahmanhood is (reduced to mere) grass, if, even though with perfect devotion to the race of gurus he strive to study the sakha (or branch of the Veda to which he belongs), the fruition of the vedas (brahma-siddhi) be dependent on kings. What can be more painful than this? Therefore, with the hand accustomed to handle kusa grass, (sacrificial) fuel, stone, ladle, ghee and oblations of grain, he seized flashing weapons, resolved to conquer the world. Quickly overcoming in fight the frontier guards of the Pallava kings, he took up his abode in an inaccessible forest situated in the middle of Sriparvata. He levied many taxes from the great Bana and other kings, from which causes the Pallava kings were made to frown. But they (those causes) also helped him to make good his resolution and carry out his designs; and he shone surrounded by them as with ornaments, aud with the preparations for a vigorous campaign. The kings of Kanchi, his enemies, coming (against him) eagerly bent upon war, he journeyed under difficult disguises and penetrating to their camping grounds by night, came upon their ocean of an army and smote them down like a powerful falcon. Eating the food of disaster and being helpless, he made them bear (after him) the sword in his hand. The Pallava kings having experienced his power, saying (to themselves)-—Even (our) valour and ancestry are not (found) worthy of salvation — quickly accepted friendship with him. By his brave deeds in battle he brought honour to the kings who followed him, and he (himself) obtained from the Pallavas the honour of a crown borne in the sprouts (pallava) of their hands ; as well as a territory bounded by the water of the dancing waves, retiring and advancing, of the Amararnnava, as far as to the limit of Premara, with an undertaking that it should not be entered (or invaded) by others. And having meditated on Senapati, together with the Mothers, he was anointed by Shadanana, whose feet are illumined by the crowns of the host of gods. His son was Kanguvarmma, surrounded on high by the sacrifices of great wars, all kings bowing before him, his head fanned by beautiful white chamaras. His son, made the sole lord of the lady the Kadambaland, was Bhagiratha, the great Sagara himself secretly born in the Kadamba-kula. Then the son of that honoured king, of widespread fame, the king Raghu, of great good fortune, like Prithu having defeated his enemies by his valour, caused the earth (prithvi) to be enjoyed by his owu race. His face marked with the weapons of his enemies in combat with opposing warriors, smiter of enemies who withstood him, versed in the path of the s'mti, a poet, liberal, skilled in many arts, and beloved by his subjects. His brother, of handsome form, his voice like the sound from the clouds, diligent in (striving for) moksha and the three objects of human desire, affectionate to his family, the king Bhagirathi, in sport the king of beasts, his fame proclaimed him throughout the world as Kakustha. Whose war, with the best (jyaya), kindness to the needy, just protection of his subjects, lifting up of the humble, honouring the chief twice-born with the best of his wealth, — his intelligence being the greatest ornament to this king who was an ornament to his family, — caused the kings to consider him as Kakustha, the friend of the gods, come here. As herds of deer tormented by the heat, entering into groups of trees, take refuge in their shade and obtain relief for their panting minds, so relatives and dependents exposed to injury from superiors (jyaya) obtained comfort to their troubled minds by entering his country. With their accumulation of all manner of the essence of wealth, with gateways scented with the ichor from lordly lusty elephants, with the sweet sounds of songs, — the goddess of Fortune contentedly (or steadily) enjoys herself in his houses for a long time. This sun among kings, by the rays his daughters roused up the beds of lotus the families of the Gupta and other kings, whose filaments are affection, regard, love and respect, served like bees by many princes. He had the help of the gods, was surrounded by the prosperous, possessed the three energies, and was seated on a throne, reverenced by head-jewels of feudatories not to be subdued by the other five qualities. He, here, — in the Siddhi-giving temple of the divine Bhava, the original god, served by the hosts of siddha, gandharvvas and rakshasas, ever praised by Brahmans devoted to the various modes of niyama, homa and diksha, and by these who have completed study, with auspicious repetition of mantras; worshipped with devotion by Satakarni and other fortunate kings seeking to obtain moksha for themselves, — in order that it might with great ease be provided with water, — king Kakusthavarmma — made this auspicious tank. Being ordered by his son, the King Santivarma — of wide fame from new-found happiness, of a beautiful form adorned with the acquisition of three crowns, — Kubja had his own poem inscribed on the surface of this stone. Obeisance to the divine Mahadeva, dweller in Sthanaknndur. Prosperity to this place to which all from all sides come. Be it well with its people. |

- F Kielhorn 1906 translation (Epigraphica Indica, Volume 8)[2]

(Be it) accomplished ! Obeisance to Shiva

(Verse 1.) Victorious is the eternal Sthanu, whose one body is framed by the coalescence of all the gods ; who is adorned with a mass of matted hair, lustrous because inlaid with the rays of the moon.

(V. 2.) After him, (victorious are) the gods on earth, the chief of the twice-born, who recite the Sama-, Rig- and Yajur-vedas; whose favour constantly guards the three worlds from the fear of evil.

(V. 3.) And next, (victorious is) Kakusthavarman, whose form is like that of the lord of the gods (and) whose intelligence is vast; the king who is the moon in the firmament of the great lineage of the Kadamba leaders of armies.

(V. 4.) There was a high family of twice-born, the circle of whose virtues, resembling the moon's rays, was (ever) expanding; in which the sons of H&riti trod the path of the three Vedas, (and) which had sprung from the gotta of Manavya, the foremost of Rishis.

(V. 5.) Where the hair was wet from being constantly sprinkled with the holy water of the purificatory rites of manifold sacrifices; which well knew how to dive into the sacred lore, kindled the fire and drank the Soma according to precept.

(V. 6.) Where the interiors of the houses loudly resounded with the sixfold subjects of study preceded by the word Om; which promoted the increase of ample chaturmasya sacrifices, burnt-offerings, oblations, animal sacrifices, new- and full-moon and sraddha rites.

(V. 7.) Where the dwellings were ever resorted to by guests (and) the regular rites not wanting in the three libations; (and) where on a spot near the house there grew one tree with blooming Kadamba flowers.

(V. 8.) Then, as the (family) tended this tree, so there came about that sameness of name with it of (these) Brahman fellow-students, currently (accepted) as distinguishing them.

(V. 9.) In the Kadamba family thus arisen there was an illustrious chief of the twice-born named Mayurasarman, adorned with sacred knowledge, good disposition, purity and the rest.

(V. 10.) With his preceptor Virasarman he went to the city of the Pallava lords, and, eager to study the whole sacred lore, quickly entered the ghatika as a mendicant.

(Vv. 11 and 12.) There, enraged by a fierce quarrel with a Pallava horseman (he reflected): Alas, that in this Kali-age the Brahmans should be so much feebler than the Kshatriyas! For, if to one, who has duly served his preceptor's family and earnestly studied his branch of the Veda, the perfection in holiness depends on a king, what can there be more painful than this? And so

(V. 13.) With the hand dexterous in grasping the kusa-grass, the fuel, the stones, the ladle, the melted butter and the oblation-vessel, he unsheathed a flaming sword, eager to conquer the earth.

(V. 14.) Having swiftly defeated in battle the frontier-guards of the Pallava lords, he occupied the inaccessible forest stretching to the gates of Sriparvata.

(V.15 and 16.) He levied many taxes from the circle of kings headed by the Great Bana. So he shone, as with ornaments, by these exploits of his which made the Paliava lords knit their brows — exploits which were charming since his vow began to be fulfilled thereby and which secured his purpose — as well as by the starting of a powerful raid.

(V.17 and 18.) When the enemies, the kings of Kanchi, came in strength to fight him, he — in the nights when they were marching or resting in rough country, in places fit for assault — lighted upon the ocean of their army and struck it like a hawk, full of strength. (So) he bore that trouble, relying solely on the sword of his arm.

(V. 19.) The Pallava lords, having found out this strength of his as well as his valour and lineage, said that to ruin him would be no advantage, and so they quickly chose him even for a friend.

(Y. 20.) Then entering the kings' service, he pleased them by his acts of bravery in battles and obtained the honour of being crowned with a fillet, offered by the Pallavas with the sprouts (pallava) of their hands.

(V. 21.) And (he) also (received) a territory, bordered by the water of the western sea which dances with the rising and falling of its curved waves, and bounded by the (?) prehara, secured to him under the compact that others should not enter it.

(V.22 and 23.) Of him — whom Shadanana, whose lotus-feet are polished by the crowns of the assembly of the gods, anointed after meditating on Senapati with the Mothers — the son was Kangavarman, who performed lofty great exploits in terrible wars, (and) whose diadem was shaken by the white chowries - of all the chiefs of districts who bowed down (before him).

(V. 24.) His son was Bhagiratha, the one lord dear to the bride — the Kadamba country, Sagara's chief descendant in person, secretly born in the Kadamba family as king.

(V. 26.) Now the son of him who was honoured by kings was the earth's highly prosperous ruler Raghu, of widespread fame ; who, having subdued the enemies, by his valour, like Prithu, caused the earth to be enjoyed by his race.

(V. 26.) Who in fearful battles, his face slashed by the swords of the enemy, struck down the adversaries facing him ; who was well versed in the ways of sacred lore, a poet, a donor, skilled in manifold arts, and beloved of the people.

(V. 27.) His brother was Bhagiratha's son Kakustha, of beautiful form, with a voice deep as the cloud's, clever in the pursuit of salvation and the three objects of life, and kind to his lineage; a lord of men with the lion's gait, whose fame was proclaimed on the orb of the earth.

(V. 28.) Him, to whom war with the stronger, compassion for the needy, proper protection of the people, relief of the distressed; honour paid to the chief twice-born by (the bestowal of) pre-eminent wealth, were the rational ornament of a ruler (who wished to be) an ornament of his family, kings thought to be indeed Kakustha, the friend of the gods, descended here.

(V. 29.) As herds of deer, oppressed by the heat, when they enter a cluster of trees, have their minds delighted by the enjoyment of the shade and find comfort, so kinsmen with their belongings, who were waylaid by the stronger, had their minds relieved and found shelter, when they entered his territory.

(V. 30.) And in his house which contained manifold collections of choice wealth, the gateways of which were perfumed with the rutting juice of lordly elephants in rut, (and) which gaily resounded with music, the lady Fortune delighted to stay steadfast, for very long.

(V. 31.) This sun of a king by means of his rays — his daughters — caused to expand the splendid lotus-groups — the royal families of the Guptas and others, the filaments of which were attachment, respect, love and reverence (for him), and which were cherished by many bees — the kings (who served them)?

(V. 32.) Now to him, favoured by destiny, of no mean energy, endowed with the three powers, the crest-jewels of neighbouring princes bowed down (even) while he was sitting quiet — they who could not be subdued by the other five measures of royal policy together.

(V. 33.) Here, at the home of perfection of the holy primeval god Bhava, which is frequented by groups of Siddhas, Gandharvas and Rakshas, which is ever praised with auspicious recitations of sacred texts by Brahman students solely devoted to manifold vows, sacrifices and initiatory rites, (and) which was worshipped with faith by Satakarni and other pious kings seeking salvation for themselves, that king Kakuathavarman has caused to be made this great tank, a reservoir for the supply of abundant water.

(V. 34.) Abiding by the excellent commands of that (king's) own son, the wide-famed glorious king Santivarman whose beautiful body is made radiant by the putting on of three fillets, Kubja has written this poem of his own on the surface of the stone.

Obeisance to the holy Mahadeva who dwells at Sthanakundura ! May joy attend this place, inhabited by men come from all the neighbourhood ! Blessed be the people !

Significance and analysis

The Talagunda pillar inscription is composed in "wonderful literary Sanskrit", states the Sanskrit scholar Sheldon Pollock.[1] The pillar also confirms that the spread of classical Sanskrit into South India was complete by or before about 455–470 CE.[1]

The inscription attests to the importance of Kanchipuram as a center (ghatika) for advanced studies in ancient India, where the already learned Brahmin Mayurasarman from Talagunda goes with his counsellor to study the whole Veda.[7] Other inscriptions and literary evidence suggests that ghatikas were associated with Hindu temples and mathas (monasteries) in ancient India, and educated hundreds of students in different fields of knowledge. These schools received support from various kingdoms.[7][8] According to M.G.S. Narayanan, the mention of the conflict of Mayurasarman with Pallava cavalry at the ghatika suggests that the higher studies center in Kanchi was involved in military arts, and Mayursarman must have acquired his weapons and skills of war there since Mayurasarman did successfully found and establish a kingdom.[9]

The inscription is also significant for being the earliest epigraphical evidence found in Karnataka about the existence of a Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva in Talagunda, the construction of a temple water tank, and the practice of worshipping the Shiva Linga before about 450 CE.[10][11][12]

The inscription mentions many cultural values in 5th-century India with the mention of "music" and goddess of wealth (Lakshmi),[13] the practice of marriage between north Indian kingdoms and South Indian ones, cherishing a king who has "compassion for the needy, proper protection of the people, relief of the distressed" and these as "rational ornament of a ruler".[14] The inscription compares the Kadamba king to Kakutstha, or "divine Rama" of the Ramayana fame. The inscription also weaves the social and political role of a dynasty that views itself as a Brahmin, and as a generous wealth donors, benefactors to religious and social causes, while being Kashtriya-like soldiers willing to wage war against others they view as persecutors and enemy of the people.[14]

According to Michael Willis, the Talagunda inscription presents "rather more militant" form of Brahmins who had taken up the sword to address the problems of the Kali-age. Willis adds that the Talagunda inscription may also significant to helping date Manavadharmasastra (Manusmriti) to sometime in the 4th-century, and its spread in and after the 5th-century.[15]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Sheldon Pollock (1996). Jan E. M. Houben (ed.). Ideology and Status of Sanskrit: Contributions to the History of the Sanskrit Language. BRILL. p. 214. ISBN 90-04-10613-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j E. Hultzsch (editor), Epigraphica Indica 8 (1906), pp. 24-36.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Epigraphia Carnatica 7 (Sk.176), p. 200ff.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ D. C. Sircar, Select Inscriptions, p. 450ff.

- ^ B. R. Gopal, Corpus of Kadamba Inscriptions (Mysore, 1985), pp. 10ff.

- ^ G. S. Gai, Inscriptions of the Kadambas (Delhi, 1996), p. 64ff.

- ^ a b Hartmut Scharfe (2018). Education in Ancient India. BRILL. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-90-474-0147-6.

- ^ Herman Tieken and Katsuhiko Sato (2000), The "GHAṬIKĀ" of the twice-born in South Indian Inscriptions, Indo-Iranian Journal, Vol. 43, No. 3 (2000), pp. 213-223

- ^ M.G.S. Narayanan (1970). "Kandalur Salai - New light of the Nature of Aryan Expansion in South India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 32: 125–136.

- ^ George M. Moraes (1990). The Kadamba Kula: A History of Ancient and Mediaeval Karnataka. Asian Educational Services. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-81-206-0595-4.

- ^ K. S. Singh; B. G. Halbar (2003). Karnataka. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 103. ISBN 978-81-85938-98-1.

- ^ Ishwar Chandra Tyagi (1982). Shaivism in Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to C.A.D. 300. Meenakshi. p. 134.

- ^ Mantosh Chandra Choudhury and M. S. Choudhary (1985), Musical Gleanings from Select South Indian Epigraphs, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 46, pp. 671-678

- ^ a b Prachi Sharma (2017), Royal Self-representation in Early Kadamba Inscriptions, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Volume 78, pp. 59-67

- ^ This episode explored, with translation of the relevant passage of the inscription, in Michael Willis, The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual (Cambridge, 2009): pages 203–205