Safi al-Din al-Urmawi

Safi al-Din al-Urmawi al-Baghdadi (Persian: صفی الدین اورموی) or Safi al-Din Abd al-Mu'min ibn Yusuf ibn al-Fakhir al-Urmawi al-Baghdadi (born c. 1216 AD in Urmia, died in 1294 AD in Baghdad) was a renowned musician and writer on the theory of music.[1][2]

Background and life

Safi al-Din Abd al-Muʾmin ibn Yusof ibn Fakhir al-Ormawi al-Baghdadi (Sufi al-Dīn in some Ottoman sources), renowned musician and writer on the theory of music, was born c. 613 AH (1216 AD), probably in Urmiya (Iran). He died in Baghdad on 28 Ṣafar 693 AH (28 January 1294 AD), at the age of about 80. According to the Encyclopedia of Islam[3] "The sources are silent about the ethnic origin of his family. He may have been of Persian descent Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi calls him afdal-i Īrān (A sage of Iran)". Based on its terminology, Al-Urmawi's 'international' modal system was intended to represent the predominant Arab and Persian local traditions.[4]

In his youth, he went to Baghdad and was educated in the Arabic language, literature, history and penmanship. He made a name for himself as an excellent calligrapher and was appointed copyist at the new library built by the Abbasid caliph al-Mustaṣim.

He had also studied Shafii law [3] and comparative law (Khilaf Fiqh) at the Mustansiriyya Madrasa which opened in 631 AH (1234 AD). This qualified him to assume a post in al-Mustaʿsim's juridical administration and, after 656 AH (1258), to head the supervision of the foundations (naẓariyyat al-waqf) in Iraq until 665 AH (1267), when Nasir al-Din Tusi took over.

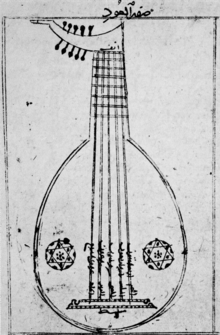

al-Urmawi became known as a musician and excellent lute (‘Ud) player and accepted as a member of the private circle of boon companions, thanks to one of his music students, the caliph's favoured songstress Luḥaẓ. His musical talent made him survive the fall of Baghdad, by generously accommodating one of Hulagu’s officer. Hulagu the Mongol ruler was impressed by al-Urmawi and doubled his income relative to the Abbasid era.

His musical career, however, seems to have been supported mainly by the Juvayni family, especially by Shams al-Din Juvayni and his son Sharaf al-Din Harun Juvayni who was put to death in 685 AH (1285). After the demise of his patrons, he fell into oblivion and poverty. He was placed under arrest on account of a debt of 300 dinars. He died in the Shafi'i Madrasat al-Khalil in Baghdad.

Music and music theory

As a composer, al-Urmawi cultivated the vocal forms of ṣawt, qawl and nawba. In the anonymous Persian Kanz al-tuḥaf of the 8th century AH (14th century AD), he is also credited with the invention of two stringed musical instruments, the nuzha and the mughnī.[5]

Al-Urmawi's most important work are two books in Arabic Language on music theory, the Kitab al-Adwār[6] and Risālah al-Sharafiyyah fi 'l-nisab al-taʾlifiyyah. The first book was written while he still worked in the library of al-Mustasim. The Abbasid caliph was well known for his addiction to music. The second book was dedicated to Sharaf al-Din Harun Juvayni who ordered him to compile it.

The Kitab al-Adwār is the first extant work on scientific music theory after the writings on music of Avicenna.[3] It contains valuable information on the practice and theory of music in the Perso-ʿIraqi[3] area, such as the factual establishment of the five-stringed lute (still an exception in Avicenna’s time), the final stage in the division of the octave into 17 steps, the complete nomenclature and definition of the scales constituting the system of the twelve Makams (called shudūd) and the six Awāz modes.[3] It also contains precise depictions of contemporary musical metres, and the use of letters and numbers for the notation of melodies. It is the first time that this occurs in history, making it a unique work of greatest value.[3] Al-Urmawi's 'international' modal system was intended to represent the predominant Arab and Persian local musical traditions.[7]

By its conciseness it became the most popular and influential book on music for centuries. No other Arabic (Persian or Ottoman Turkish) music treatise was so often copied, commented upon and translated into Oriental (and Western) languages.[3] The Kitab al-Adwār was conceived as a compendium (mukhtasar) of the standard musical knowledge of its time.

The Kitab al-Adwār was translated several times into Persian language and there also exists an Ottoman Turkish translation.[3]

Al-Urmawi’s second book, Risāla al-Sharafiyya, was written around 665 AH (1267 AD).[3] It is dedicated to his student and later patron, Sharaf al-Din Harun Juvayni (Juvayn is a town in Khorasan). He was part of the scientific, literary and artistic circle of the Juvayni family. Through these gatherings, al-Urmawi was in contact with the Persian scholar Nasir al-Din Tusi. Nasir al-Din Tusi, who left a short treatise on the proportions of musical intervals perceivable in the pulse may have stimulated al-Urmawī's interest in Greek science and music theory.[3]

These two major books have become the foundation of academic discourse on Arabic music, most notably modern works by Briton Owen Wright.[8] [9] Commentaries on these theoretical works were written as early as the 1370s.[10][11]

Musical modes of Urmawi

The list of the modes and āwaz (singing) modes are taken from (E. Neubaer, "Music in the Islamic Environment" in Clifford Edmund Bosworth, M.S.Asimov, "History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 4, Part 2", ilal Banarsidass Publ., 2003 - 745 pages. pg 597.).[12] The majority of the modes have Iranian/Persian names and the rest have Arabic names (some with Persian suffix 'i').

Parda

- 'Ushshāq (Arabic name)

- nawā (Iranian name)

- busalik (also called AbuSalik)

- rāst (Iranian name)

- 'irāq (Arabic name)

- isfahān (Iranian name)

- zirāfkand (Iranian name)

- buzurk (buzurg) (Iranian name)

- zankulā (zangulā) (Iranian name)

- rāhawi (rāhavi) (Iranian name)

- husayni (Arabic name with Iranian suffix i)

- hijazi (Arabic name with Iranian suffix i)

Āwāz mode

- kardāniya (gardāniya) (Iranian name)

- kawāsht (gawāsht) (Iranian name)

- nawruz (Iranian name)

- māya (Iranian name)

- shahnāz (Iranian name)

- salmak (Iranian name)

See also

References

- ^ Bosworth, C.E., ed. (1995). Ṣanʻaʼ - Ṣawtiyya (New ed.). Leiden [u.a.]: Brill [u.a.] p. 805. ISBN 978-9004098343.

He may have been of Persian descent (Kutb al-Din Shirazi [q.v.] calls him afdal-i Iran)

- ^ van Gelder, Geert Jan (1 January 2012). "SING ME TO SLEEP: ṢAFĪ AL-DĪN AL-URMAWĪ, HÜLEGÜ, AND THE POWER OF MUSIC". Quaderni di Studi Arabi. 7: 1–9.

His ethnic origin is uncertain; he may have been of Persian descent.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j E., Neubauer. "ṢAFĪ al-DĪN al-URMAWĪ". Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_sim_6447.

- ^ E. Neubaer, "Music in the Islamic World", in Clifford Edmund Bosworth, M.S.Asimov, "History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 4, Part 2", pg 596. [1]. excerpt: "To judge from its terminology, al-Urmawi's international modal system was intended to represent the predominant Arab and Persian local traditions.

- ^ See H. G. Farmer, Studies in oriental musical instruments, First Series, London 1931.

- ^ "Kitāb al-Adwār fī al-mūsīqá.; Adwār fī al-mūsīqá - Colenda Digital Repository". colenda.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "History of Civilizations of Central Asia", Contributor Clifford Edmund Bosworth, M.S. Asimov,.Motilal Banarsidass Publ, 2002. pg 596

- ^ Wright, O. (1 January 1995). "'Abd al-Qādir al-Marāghī and 'Alī b. Muḥammad Binā'ī: Two Fifteenth-Century Examples of Notation Part 2: Commentary". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 58 (1): 17–39. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00011836. JSTOR 619996.

- ^ Wright, O. (1 January 1995). "A Preliminary Version of the "kitāb al-Adwār"". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 58 (3): 455–478. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00012908. JSTOR 620103.

- ^ "Commentaire anonyme du Kitāb al-adwār : édition critique, traduction et présentation des lectures arabes de l’oeuvre de Ṣafī al-Dīn al-Urmawī" Anas GHRAB, 2009, thèse de doctorat, Université Paris-Sorbonne. http://anas.ghrab.tn/static/web/fichiers/2009_these.pdf

- ^ Feldman, Walter (1 January 1990). "Cultural Authority and Authenticity in the Turkish Repertoire". Asian Music. 22 (1): 73–111. doi:10.2307/834291. JSTOR 834291.

- ^ E. Neubaer, "Music in the Islamic Environment" in Clifford Edmund Bosworth, M.S.Asimov, "History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 4, Part 2", ilal Banarsidass Publ., 2003 - 745 pages. page 597)

External links

- musicologie.org – Full score (French)

- al-Urmawi's manuscript, Adilnor Collection