Mammuthus meridionalis

| Mammuthus meridionalis Temporal range: Early Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | †Mammuthus |

| Species: | †M. meridionalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Mammuthus meridionalis (Nesti, 1825)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

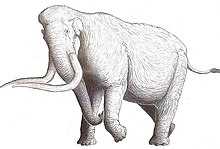

Mammuthus meridionalis, or the southern mammoth, is an extinct species of mammoth native to Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene, living from around 2.5 million years ago to 800,000 years ago.

Taxonomy

The taxonomy of extinct elephants was complicated by the early 20th century, and in 1942, Henry Fairfield Osborn's posthumous monograph on the Proboscidea was published, wherein he used various taxon names that had previously been proposed for mammoth species, including replacing Mammuthus with Mammonteus, as he believed the former name to be invalidly published.[1] Mammoth taxonomy was simplified by various researchers from the 1970s onwards, all species were retained in the genus Mammuthus, and many proposed differences between species were instead interpreted as intraspecific variation.[2] The name Archidiskodon meridionalis is retained by some Russian researchers.[3][4]

Description

With large individuals reaching a shoulder height of about 3.97–4.05 m (13.0–13.3 ft) and an estimated weight of 10.7–11.4 tonnes (11.8–12.6 short tons), M. meridionalis was a large proboscidean, exceeding the size of the largest known modern elephants.[5][6] The average male has been estimated to have had a shoulder height of 4 m (13.1 ft) and a weight of 11 tonnes (12.1 short tons).[5] Cranium fossils of the M. meridionalis found in Italy show the length of the skull to be 1.25 - 1.54 meters long.[7] It had robust twisted tusks, common of mammoths. Its molars had low crowns[8] and around 13 thick enamel ridges (lamellae), substantialy lower than the number in later mammoth species.[9] It lived on a relatively warm climate, which makes it more probable that it lacked dense fur.[8]

Diet

Dental microwear of the teeth of M. meridionalis suggest that the species was a variable mixed feeder, that consumed both grass and browse, with its diet varying according to local conditions, with some populations exhibiting browse-dominated mixed feeding, while others grass-dominant.[10]

Evolution

Since many remains of each species of mammoth are known from several localities, it is possible to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the genus through morphological studies. Mammoth species can be identified from the number of enamel ridges (or lamellar plates) on their molars: primitive species had few ridges, and the number increased gradually as new species evolved to feed on more abrasive food items. The crowns of the teeth became deeper in height and the skulls became taller to accommodate this. At the same time, the skulls became shorter from front to back to minimise the weight of the head.[11][12]

The first known members of the genus Mammuthus are the African species M. subplanifrons from the Pliocene, and M. africanavus from the Pleistocene. The former is thought to be the ancestor of later forms. Mammoths entered Europe around 3 million years ago. The earliest European mammoth has been named M. rumanus; it spread across Europe and China. Only its molars are known, which show that it had 8–10 enamel ridges. A population evolved 12–14 ridges, splitting off from and replacing the earlier type, becoming M. meridionalis about 2–1.7 million years ago. In turn, a population of M. meridionalis evolved into the steppe mammoth (M. trogontherii) with 18–20 ridges, in eastern Asia around 2–1.5 million years ago.[11] The Columbian mammoth (M. columbi) evolved from a population of M. trogontherii that had crossed the Bering Strait and entered North America about 1.5 million years ago, and not M. meridionalis as had been suggested earlier.[9] This was confirmed by a 2016 a genetic study of North American mammoth specimens.[13] Steppe mammoths replaced M. meridionalis in Europe in a diachronous mosaic pattern between 1 and 0.8-0.7 million years ago.[11]

Distribution and habitat

Fossilized plants found with the remains show that M. meridionalis was living in a time of mild climate, generally as warm or slightly warmer than Europe experiences today. Deciduous mixed wood provided its habitat and food, which consisted mostly of tree-browse: oak, ash, beech and other familiar European trees, as well as some that are now exotic to the region, such as hemlock, wing nut and hickory. Complete skeletons are in Stavropol State Museum in Russia, in L'Aquila National Museum and in Firenze at the Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze in Italy. Further east, discoveries at Ubeidiya (Israel) and Dmanisi (Georgia) show the early mammoth living in a partially open habitat with grassy areas.[8]

During the early part of its existence in Europe, it existed alongside the "tetralophodont gomphothere" Anancus arvernensis. Dietary analysis based on microwear suggests that there was niche partitioning between the two species, with M. meridonalis occupying more open habitats.[14]

Relationship with humans

At the Fuente Nueva-3 and Barranc de la Boella sites in Spain, dating to approximately 1.3 and 1-0.8 million years ago respectively, remains of M. meridionalis are associated with stone tools (in the latter site of the Acheulean type), primarily lithic flakes. At Barranc de la Boella, some rib bones possibly bear cut marks, but at Fuente Nueva-3, which has poorly preserved bone surfaces, no cuts marks have been found. Both sites are suggested to represent evidence of butchery by archaic humans.[15]

References

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1942). Percy, M. R. (ed.). Proboscidea: A monograph of the discovery, evolution, migration and extinction of the mastodonts and elephants of the world. Vol. 2. New York: J. Pierpont Morgan Fund. pp. 1116–1169.

- ^ Maglio, V. J. (1973). "Origin and evolution of the Elephantidae". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 63 (3): 1–149. doi:10.2307/1379357. JSTOR 1379357.

- ^ Shchelinsky, V.E. (April 2020). "Large mammal hunting and use of aquatic food resources in the Early Palaeolithic (finds from Early Acheulean sites in the southern Azov Sea region)". Quaternary International. 541: 182–188. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.04.008. S2CID 216338569.

- ^ Baigusheva, Vera S.; Titov, Vadim V.; Foronova, Irina V. (October 2016). "Teeth of early generations of Early Pleistocene elephants (Mammalia, Elephantidae) from Sinyaya Balka/Bogatyri site (Sea of Azov Region, Russia)". Quaternary International. 420: 306–318. Bibcode:2016QuInt.420..306B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.007. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ a b Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- ^ Romano, Marco; Manucci, Fabio; Antonelli, Matteo; Rossi, Maria Adelaide; Agostini, Silvano; Palombo, Maria Rita (2022-07-14). "In vivo restoration and volumetric body mass estimate of Mammuthus meridionalis from Madonna della Strada (Scoppito, L'Aquila)". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 128 (3). doi:10.54103/2039-4942/16665. ISSN 2039-4942. S2CID 250580462.

- ^ Ferretti, Marco P. (1999). "Mammuthus meridionalis (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Elephantidae) from the 'Sabbie Gialle' of Oriolo (Cava La Salita, Faenza, Northern Italy) and other European late populations of southern mammoth". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetia. 92 (3): 503–515.

- ^ a b c Lister, Adrian; Bahn, Paul (2007). Mammoths: giants of the ice age. Frances Lincoln LTD. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780711228016.

- ^ a b Lister, A. M.; Sher, A. V. (2015-11-13). "Evolution and dispersal of mammoths across the Northern Hemisphere". Science. 350 (6262): 805–809. Bibcode:2015Sci...350..805L. doi:10.1126/science.aac5660. PMID 26564853. S2CID 206639522.

- ^ Rivals, Florent; Semprebon, Gina M.; Lister, Adrian M. (September 2019). "Feeding traits and dietary variation in Pleistocene proboscideans: A tooth microwear review". Quaternary Science Reviews. 219: 145–153. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.06.027. S2CID 200073388.

- ^ a b c Lister, A. M.; Sher, A. V.; Van Essen, H.; Wei, G. (2005). "The pattern and process of mammoth evolution in Eurasia" (PDF). Quaternary International. 126–128: 49–64. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126...49L. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.014.

- ^ Ferretti, M. P. (2003). "Structure and evolution of mammoth molar enamel". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 3. 48: 383–396.

- ^ Enk, J.; Devault, A.; Widga, C.; Saunders, J.; Szpak, P.; Southon, J.; Rouillard, J. M.; Shapiro, B.; Golding, G. B.; Zazula, G.; Froese, D.; Fisher, D. C.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Poinar, H. (2016). "Mammuthus population dynamics in Late Pleistocene North America: divergence, phylogeography, and introgression". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00042.

- ^ Rivals, Florent; Mol, Dick; Lacombat, Frédéric; Lister, Adrian M.; Semprebon, Gina M. (2015-08-27). "Resource partitioning and niche separation between mammoths (Mammuthus rumanus and Mammuthus meridionalis) and gomphotheres (Anancus arvernensis) in the Early Pleistocene of Europe". Quaternary International. Mammoths and their Relatives: VIth International Conference, Grevena-Siatista, Greece, part 1. 379: 164–170. Bibcode:2015QuInt.379..164R. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.12.031. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Haynes, Gary (March 2022). "Late Quaternary Proboscidean Sites in Africa and Eurasia with Possible or Probable Evidence for Hominin Involvement". Quaternary. 5 (1): 18. doi:10.3390/quat5010018. ISSN 2571-550X.

Bibliography

- Lister, A.; Bahn, P. (2007). Mammoths - Giants of the Ice Age (3 ed.). London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-520-26160-0.

External links

![]() Media related to Mammuthus meridionalis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mammuthus meridionalis at Wikimedia Commons