Digital identity

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Digital identity refers to the information utilized by computer systems to represent external entities, including a person, organization, application, or device. When used to describe an individual, it encompasses a person's compiled information and plays a crucial role in automating access to computer-based services, verifying identity online, and enabling computers to mediate relationships between entities. Digital identity for individuals is an aspect of a person's social identity and can also be referred to as online identity.

The widespread use of digital identities can include the entire collection of information generated by a person's online activity. This includes usernames, passwords, search history, birthday, social security number, and purchase history. When publicly available, this data can be used by others to discover a person's civil identity. It can also be harvested to create what has been called a "data double", an aggregated profile based on the user's data trail across databases. In turn, these data doubles serve to facilitate personalization methods on the web and across various applications.[1][2]

If personal information is no longer the currency that people give for online content and services, something else must take its place. Media publishers, app makers, and e-commerce shops are now exploring different paths to surviving a privacy-conscious internet, in some cases overturning their business models. Many are choosing to make people pay for what they get online by levying subscription fees and other charges instead of using their personal data.[3]

An individual's digital identity is often linked to their civil or national identity and many countries have instituted national digital identity systems that provide digital identities to their citizenry.

The legal and social effects of digital identity are complex and challenging. Faking a legal identity in the digital world may present many threats to a digital society and raises the opportunity for criminals, thieves, and terrorists to commit various crimes. These crimes may occur in either the online world, real world, or both.[4]

Background

A critical problem in cyberspace is knowing with whom one is interacting. Using only static identifiers such as passwords and email, there is no way to precisely determine the identity of a person in cyberspace because this information can be stolen or used by many individuals acting as one. Digital identity based on dynamic entity relationships captured from behavioral history across multiple websites and mobile apps can verify and authenticate identity with up to 95% accuracy.

By comparing a set of entity relationships between a new event (e.g., login) and past events, a pattern of convergence can verify or authenticate the identity as legitimate whereas divergence indicates an attempt to mask an identity. Data used for digital identity is generally anonymized using a one-way hash, thereby avoiding privacy concerns. Because it is based on behavioral history, a digital identity is very hard to fake or steal.

Related information

A digital identity may also be referred to as a digital subject or digital entity. They are the digital representation of a set of claims made by one party about itself or another person, group, thing, or concept. A digital twin[5] which is also commonly known as a data double or virtual twin is a secondary version of the original user's data. Which is used both as a way to surveillance what said user does on the internet as well as customize a more personalized internet experience.[citation needed] Due to the collection of personal data, there have been many social, political, and legal controversies tying into data doubles.

Attributes, preferences, and traits

The attributes of a digital identity are acquired and contain information about a user, such as medical history, purchasing behavior, bank balance, age, and so on. Preferences retain a subject's choices such as favorite brand of shoes, and preferred currency. Traits are features of the user that are inherent, such as eye color, nationality, and place of birth. Although attributes of a user can change easily, traits change slowly, if at all. A digital identity also has entity relationships derived from the devices, environment, and locations from which an individual is active on the Internet. Some of those include facial recognition, fingerprints, photos, and so many more personal attributes/preferences.[6]

Technical aspects

Issuance

Digital identities can be issued through digital certificates. These certificates contain data associated with a user and are issued with legal guarantees by recognized certification authorities.

Trust, authentication and authorization

In order to assign a digital representation to an entity, the attributing party must trust that the claim of an attribute (such as name, location, role as an employee, or age) is correct and associated with the person or thing presenting the attribute. Conversely, the individual claiming an attribute may only grant selective access to its information (e.g., proving identity in a bar or PayPal authentication for payment at a website). In this way, digital identity is better understood as a particular viewpoint within a mutually-agreed relationship than as an objective property.[citation needed]

Authentication

Authentication is the assurance of the identity of one entity to another. It is a key aspect of digital trust. In general, business-to-business authentication is designed for security, but user-to-business authentication is designed for simplicity.

Authentication techniques include the presentation of a unique object such as a bank credit card, the provision of confidential information such as a password or the answer to a pre-arranged question, the confirmation of ownership of an email address, and more robust but costly techniques using encryption. Physical authentication techniques include iris scanning, fingerprinting, and voice recognition; those techniques are called biometrics. The use of both static identifiers (e.g., username and password) and personal unique attributes (e.g., biometrics) is called multi-factor authentication and is more secure than the use of one component alone.

Whilst technological progress in authentication continues to evolve, these systems do not prevent aliases from being used. The introduction of strong authentication[citation needed] for online payment transactions within the European Union now links a verified person to an account, where such person has been identified in accordance with statutory requirements prior to account being opened. Verifying a person opening an account online typically requires a form of device binding to the credentials being used. This verifies that the device that stands in for a person on the Internet is actually the individual's device and not the device of someone simply claiming to be the individual. The concept of reliance authentication makes use of pre-existing accounts, to piggy back further services upon those accounts, providing that the original source is reliable. The concept of reliability comes from various anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism funding legislation in the US,[7] EU28,[8] Australia,[9] Singapore and New Zealand[10] where second parties may place reliance on the customer due diligence process of the first party, where the first party is say a financial institution. An example of reliance authentication is PayPal's verification method.

Authorization

Authorization is the determination of any entity that controls resources that the authenticated can access those resources. Authorization depends on authentication, because authorization requires that the critical attribute (i.e., the attribute that determines the authorizer's decision) must be verified.[citation needed] For example, authorization on a credit card gives access to the resources owned by Amazon, e.g., Amazon sends one a product. Authorization of an employee will provide that employee with access to network resources, such as printers, files, or software. For example, a database management system might be designed so as to provide certain specified individuals with the ability to retrieve information from a database but not the ability to change data stored in the database, while giving other individuals the ability to change data.[citation needed]

Consider the person who rents a car and checks into a hotel with a credit card. The car rental and hotel company may request authentication that there is credit enough for an accident, or profligate spending on room service. Thus a card may later be refused when trying to purchase an activity such as a balloon trip. Though there is adequate credit to pay for the rental, the hotel, and the balloon trip, there is an insufficient amount to also cover the authorizations. The actual charges are authorized after leaving the hotel and returning the car, which may be too late for the balloon trip.

Valid online authorization requires analysis of information related to the digital event including device and environmental variables. These are generally derived from the data exchanged between a device and a business server over the Internet.[11]

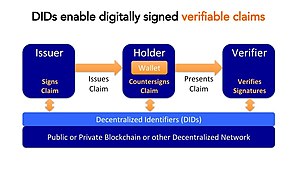

Digital identifiers

Digital identity requires digital identifiers—strings or tokens that are unique within a given scope (globally or locally within a specific domain, community, directory, application, etc.).

Identifiers may be classified as omnidirectional or unidirectional.[12] Omnidirectional identifiers are public and easily discoverable, whereas unidirectional identifiers are intended to be private and used only in the context of a specific identity relationship.

Identifiers may also be classified as resolvable or non-resolvable. Resolvable identifiers, such as a domain name or email address, may be easily dereferenced into the entity they represent, or some current state data providing relevant attributes of that entity. Non-resolvable identifiers, such as a person's real name, or the name of a subject or topic, can be compared for equivalence but are not otherwise machine-understandable.

There are many different schemes and formats for digital identifiers. Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) and the internationalized version Internationalized Resource Identifier (IRI) are the standard for identifiers for websites on the World Wide Web. OpenID and Light-weight Identity are two web authentication protocols that use standard HTTP URIs (often called URLs). A Uniform Resource Name is a persistent, location-independent identifier assigned within the defined namespace.

Digital object architecture

Digital object architecture[13] is a means of managing digital information in a network environment. In digital object architecture, a digital object has a machine and platform independent structure that allows it to be identified, accessed and protected, as appropriate. A digital object may incorporate not only informational elements, i.e., a digitized version of a paper, movie or sound recording, but also the unique identifier of the digital object and other metadata about the digital object. The metadata may include restrictions on access to digital objects, notices of ownership, and identifiers for licensing agreements, if appropriate.

Handle System

The Handle System is a general purpose distributed information system that provides efficient, extensible, and secure identifier and resolution services for use on networks such as the internet. It includes an open set of protocols, a namespace, and a reference implementation of the protocols. The protocols enable a distributed computer system to store identifiers, known as handles, of arbitrary resources and resolve those handles into the information necessary to locate, access, contact, authenticate, or otherwise make use of the resources. This information can be changed as needed to reflect the current state of the identified resource without changing its identifier, thus allowing the name of the item to persist over changes of location and other related state information. The original version of the Handle System technology was developed with support from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

Extensible resource identifiers

A new OASIS standard for abstract, structured identifiers, XRI (Extensible Resource Identifiers), adds new features to URIs and IRIs that are especially useful for digital identity systems. OpenID also supports XRIs, which are the basis for i-names.

Risk-based authentication

Risk-based authentication is an application of digital identity whereby multiple entity relationship from the device (e.g., operating system), environment (e.g., DNS Server) and data entered by a user for any given transaction is evaluated for correlation with events from known behaviors for the same identity.[14] Analysis are performed based on quantifiable metrics, such as transaction velocity, locale settings (or attempts to obfuscate), and user-input data (such as ship-to address). Correlation and deviation are mapped to tolerances and scored, then aggregated across multiple entities to compute a transaction risk-score, which assess the risk posed to an organization.

Policy aspects

There are proponents of treating self-determination and freedom of expression of digital identity as a new human right. Some have speculated that digital identities could become a new form of legal entity.[15] As technology develops so does the intelligence of certain digital identities, moving forward many believe that there should be more developments in legal aspects that regulate online presences and collection.

Taxonomies of identity

Digital identity attributes exist within the context of ontologies.

The development of digital identity network solutions that can interoperate taxonomically diverse representations of digital identity is a contemporary challenge. Free-tagging has emerged recently as an effective way of circumventing this challenge (to date, primarily with application to the identity of digital entities such as bookmarks and photos) by effectively flattening identity attributes into a single, unstructured layer. However, the organic integration of the benefits of both structured and fluid approaches to identity attribute management remains elusive.

Networked identity

Identity relationships within a digital network may include multiple identity entities. However, in a decentralized network like the Internet, such extended identity relationships effectively requires both the existence of independent trust relationships between each pair of entities in the relationship and a means of reliably integrating the paired relationships into larger relational units. And if identity relationships are to reach beyond the context of a single, federated ontology of identity (see Taxonomies of identity above), identity attributes must somehow be matched across diverse ontologies. The development of network approaches that can embody such integrated "compound" trust relationships is currently a topic of much debate in the blogosphere.

Integrated compound trust relationships allow, for example, entity A to accept an assertion or claim about entity B by entity C. C thus vouches for an aspect of B's identity to A.

A key feature of "compound" trust relationships is the possibility of selective disclosure from one entity to another of locally relevant information. As an illustration of the potential application of selective disclosure, let us suppose a certain Diana wished to book a hire car without disclosing irrelevant personal information (using a notional digital identity network that supports compound trust relationships). As an adult, UK resident with a current driving license, Diana might have the UK's Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency vouch for her driving qualification, age, and nationality to a car-rental company without having her name or contact details disclosed. Similarly, Diana's bank might assert just her banking details to the rental company. Selective disclosure allows for appropriate privacy of information within a network of identity relationships.

A classic form of networked digital identity based on international standards is the "White Pages".

An electronic white pages links various devices, like computers and telephones, to an individual or organization. Various attributes such as X.509v3 digital certificates for secure cryptographic communications are captured under a schema, and published in an LDAP or X.500 directory. Changes to the LDAP standard are managed by working groups in the IETF, and changes in X.500 are managed by the ISO. The ITU did significant analysis of gaps in digital identity interoperability via the FGidm (ƒfocus group on identity management).

Implementations of X.500[2005] and LDAPv3 have occurred worldwide but are primarily located in major data centers with administrative policy boundaries regarding sharing of personal information. Since combined X.500 [2005] and LDAPv3 directories can hold millions of unique objects for rapid access, it is expected to play a continued role for large scale secure identity access services. LDAPv3 can act as a lightweight standalone server, or in the original design as a TCP-IP based Lightweight Directory Access Protocol compatible with making queries to a X.500 mesh of servers which can run the native OSI protocol.

This will be done by scaling individual servers into larger groupings that represent defined "administrative domains", (such as the country level digital object) which can add value not present in the original "White Pages" that was used to look up phone numbers and email addresses, largely now available through non-authoritative search engines.

The ability to leverage and extend a networked digital identity is made more practicable by the expression of the level of trust associated with the given identity through a common Identity Assurance Framework.

Security and privacy issues

Several writers have pointed out the tension between services that use digital identity on the one hand and user privacy on the other.[1][2][3][4][5] Services that gather and store data linked to a digital identity, which in turn can be linked to a user's real identity, can learn a great deal about individuals. GDPR is one attempt to address this concern using the regulation. This regulation tactic was introduced by the European Union (EU) in 2018 for addressing concerns about the privacy and personal data of EU citizens. GDPR applies to all companies, regardless of location, that handle users within the EU. Any company that collects, stores, and operates with data from EU citizens must disclose key details about the management of that data to EU individuals. EU citizens can also request for certain aspects of their collected data to be deleted.[16] To help enforce GDPR, the EU has applied penalties to companies that operate with data from EU citizens but fail to follow the regulations[17]

Many systems provide privacy-related mitigations when analyzing data linked to digital identities. One common mitigation is data anonymization, such as hashing user identifiers with a cryptographic hash function. Another popular technique is adding statistical noise to a data set to reduce identifiability, such as in differential privacy. Although a digital identity allows consumers to transact from anywhere and more easily manage various ID cards, it also poses a potential single point of compromise that malicious hackers can use to steal all of that personal information.[6]

Hence, several different account authentication methods have been created to protect users. Initially, these authentication methods will require a setup from the user to enable these security features when attempting a login.

- Two-factor Authentication: This form of authentication is a two-layered security process. The first layer will require the password for the account the user is trying to access. Following a successful password input, the second layer of security will then prompt the user to prove that they have access to something which they would only have. Typically, these are unique one-time generated security codes that will be sent to the email or phone number registered on the account. Successful input of these unique one-time generated security codes will then grant the user permission into the account. There are also maybe options for answering security questions that will grant access to the account, something which only the actual user would know the answers too.[18] The second layer of the two-factor authentication process can also include face biometric factors such as facial scans, fingerprints, or a voice print rather than one-time generates security codes or answering security questions. It is important to note that two-factor authentication will typically be required every time when attempting a login to an account[19]

- Certificate-Based Authentication: This form of authentication prioritizes the use of digital certificates, typically an individual's driver's license or a passport as a form of an electronic document. A certification authority will then prove ownership of a public key to the owner of that digital certificate. Certificate-based authorities will prioritize these electronic documents to identify a user. When signing into a server, the individual presents their digital certificate, the server will then verify the credibility of that digital certificate through cryptography, and the authentication process is finally complete when that private key is certified[20]

Social aspects

Digital rhetoric[importance?]

This subsection is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (June 2022) |

The term 'digital identity' is utilized within the academic field of digital rhetoric to refer to identity as a 'rhetorical construction'.[21] Digital rhetoric explores how identities are formed, negotiated, influenced, or challenged within the ever-evolving digital environments. Understanding different rhetorical situations in digital spaces is complex but crucial for effective communication, as scholars argue that the ability to evaluate such situations is necessary for constructing appropriate identities in varying rhetorical contexts.[22][23][24] Furthermore, it is important to recognize that physical and digital identities are intertwined, and the visual elements in online spaces shape the representation of one's physical identity.[25] As Bay suggests, 'what we do online now requires more continuity—or at least fluidity—between our online and offline selves'.[25]

Regarding the positioning of digital identity in rhetoric, scholars pay close attention to how issues of race, gender, agency, and power manifest in digital spaces. While some radical theorists initially posited that cyberspace would liberate individuals from their bodies and blur the lines between humans and technology,[26] others theorized that this 'disembodied' communication could potentially free society from discrimination based on race, sex, gender, sexuality, or class.[27] Moreover, the construction of digital identity is intricately tied to the network. This is evident in the practices of reputation management companies, which aim to create a positive online identity to increase visibility in various search engines.[21]

Impacts of Digital Identity in a Social and Governmental Aspect

Digital identity has numerous impacts on society, individuals, and nations. One of the most significant impacts is on privacy. Digital identities can be used to track an individual's online activities and gather information about their interests, behaviors, and preferences. This information can then be used by companies and governments to target individuals with personalized ads and messages or to monitor their activities for security or law enforcement purposes. As Chaffer and Goldston (2022) argue, this raises important questions about the balance between privacy and security, and the rights of individuals to control their own data.[28][21]

Another impact of digital identity is on social relationships. Digital identities allow individuals to connect and communicate with others across great distances and cultural divides. However, they can also create new forms of inequality and exclusion, as those who lack access to digital technologies or are unable to navigate them effectively may be left behind. This is especially true in developing countries or among marginalized groups, where access to digital technologies may be limited or controlled by those in power. An individual's digital identity is often linked to their civil or national identity and many countries have instituted national digital identity systems that provide digital identities to their citizenry. Such digital identity systems are personal, biometric, and social identifiers. This may typically include the name and date of birth of an individual. Biometric identifiers refer to the biological traits of an individual, mainly physical characteristics: hair color, iris/retina patterns, fingerprints, height, and weight. Social identifiers revolve around the individual's sociological and psychological with the world and its inhabitants.[29]

At the national level, digital identity systems can have a profound impact on political power and social control. Governments may use digital identity systems to monitor and control their citizens' activities, restrict access to certain services or information, or target individuals for surveillance or harassment. This can have serious implications for democracy, human rights, and social justice, as it can undermine the ability of individuals to speak out and participate in public life[30]

The legal and social effects of digital identity are complex and challenging.[further explanation needed]. Faking a legal identity in the digital world may present many threats to a digital society and raises the opportunity for criminals, thieves, and terrorists to commit various crimes. These crimes may occur in either the online world, the real world, or both.[31]

Legal issues

Clare Sullivan presents the grounds for digital identity as an emerging legal concept. The UK's Identity Cards Act 2006 confirms Sullivan's argument and unfolds the new legal concept involving database identity and transaction identity. Database identity is the collection of data that is registered about an individual within the databases of the scheme and transaction identity is a set of information that defines the individual's identity for transactional purposes. Although there is reliance on the verification of identity, none of the processes used are entirely trustworthy. The consequences of digital identity abuse and fraud are potentially serious since in possible implications the person is held legally responsible.[32]

Business aspects

Corporations are recognizing the power of the internet to tailor their online presence to each individual customer. Purchase suggestions, personalized adverts, and other tailored marketing strategies are a great success for businesses. Such tailoring, however, depends on the ability to connect attributes and preferences to the identity of the visitor. For technology to enable direct value transfer of rights and non-bearer assets, human agency must be conveyed, including the authorization, authentication, and identification of the buyer and/or seller, as well as “proof of life,” without a third party. A solution to confirm legal identities resulted from the financial crisis of 2008. The Global LEI System would be able to provide every registered business in the world with an LEI. The LEI - Legal Entity Identifier provides businesses permanent identification worldwide for legal identities.

The LEI[33] is:

- 20-digit, alpha-numeric code based on the ISO 17442 standard.

- Designed to be used and recognized globally.

- The identifier for legal entities involved in digital transactions.

- Decentralized and used in an open data system that allows its identification data to be accessed by anyone.

- Incorporates in-depth validation services in each part of its process.

Digital death

Digital death is the phenomenon of people continuing to have Internet accounts after their deaths. This results in several ethical issues concerning how the information stored by the deceased person may be used or stored or given to the family members. It also may result in confusion due to automated social media features such as birthday reminders, as well as uncertainty about the deceased person's willingness to pass their personal information to a third party. Many social media platforms do not have clear policies about digital death. Many companies secure digital identities after death or legally pass those on to the deceased people's families. Some companies will also provide options for digital identity erasure after death. Facebook/Meta is a clear-cut example of a company that provides digital options after death. Descendants or friends of the deceased individual can let Facebook know about the death and have all of their previous digital activity removed. Digital activity is but not limited to messages, photos, posts, comments, reactions, stories, archived history, etc. Furthermore, the entire Facebook account will be deleted upon request.[34]

National digital identity systems

Although many facets of digital identity are universal owing in part to the ubiquity of the Internet, some regional variations exist due to specific laws, practices, and government services that are in place. For example, digital identity can use services that validate driving licences, passports and other physical documents online to help improve the quality of a digital identity. Also, strict policies against money laundering mean that some services, such as money transfers need a stricter level of validation of digital identity. Digital identity in the national sense can mean a combination of single sign on, and/or validation of assertions by trusted authorities (generally the government).[citation needed]

Countries or regions with official or unofficial digital identity systems include:

- China[35][36]

- India (Aadhaar card)[37]

- Iran (Iranian National smart card ID)[38]

- Singapore (SingPass and CorpPass)[39]

- Estonia (Estonian identity card)[40]

- Germany[41][42]

- Italy (Sistema Pubblico di Identità Digitale)[43]

- Monaco[44]

- Ukraine (Diia)[45][46]

- UK (GOV.UK Verify)[47][needs update]

- Australia (MyGovID[48] and Australia Post Digital iD[49])

- United States (Social Security numbers)[50]

- In 2021, the 117th Congressional session introduced H.R. 4258, also named Improving Digital Identity Act of 2021,[51] in an effort to establish a governmentwide approach to improving digital ID.[52] It was turned over to the Committee on Oversight and Reform.[53] Additional efforts were ordered in October 2022 by U.S. Senators Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., and Cynthia Lummis, R-Wy.[54] with S. 4528, Improving Digital Identity Act of 2022, from the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. This new order is trying to establish a task force to coordinate federal, state, and private-sector efforts to develop digital identity credentials, such as driver's licenses, passports, and birth certificates.[55]

- In 2022, the US State of California started piloting a Digital ID program for their citizens for access to digital government services.[56]

- Dominican Republic[57]

- Canada

- Canada is actively working on providing its citizens with forms of Digital ID in partnership with the non-profit Digital ID & Authentical Council of Canada (DIACC). DIACC will also oversee the Voila Verified Trustmark Program which will provide verification of compliance standards, specifically ISO standards, as a way to certify Digital ID service providers against the Pan-Canadian Trust Framework.[58] As of 2023, there isn't a nationwide Digital ID program however the province of Alberta supports its own unique version of a Digital ID. Ontario and Quebec have plans to launch their Digital ID but were delayed by the COVID-19 Pandemic.[59]

- The Canadian Public Sector has developed the Public Sector Profile of the Pan-Canadian Trust Framework .[60] This framework has been used by the Government of Canada to assess the Province of Alberta and the Province of British Columbia and accepted their program as trusted digital identities for use by federal government services. Provincial residents can now register and sign in with their province their My Service Canada Account

- The Digital Governance Council, an accredited standards development organization, has published a national standard CAN/CIOSC 103:2020 Digital Trust and Identity and is developing conformity assessment schemes for public sector and regulated programs.

- Bhutan[61]

Countries or regions with proposed digital identity systems include:

- European Union (European Digital Identity)[62][63]

- Jamaica[64]

- Turks and Caicos/Caribbean[65]

See also

- Account verification

- Digital footprint

- Digital rhetoric

- Death and the Internet

- E-authentication

- Federated identity

- Identity-based security

- Informational self-determination

- Online identity

- Online identity management

- Privacy by design

- Real-name system

- Self-sovereign identity

- User profile

References

- ^ Jones, Kyle M. L. (May 1, 2018). "What is a data double?". Data Doubles. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ Haggerty, Kevin D.; Ericson, Richard V. (December 2000). "The surveillant assemblage" (PDF). British Journal of Sociology. 51 (4): 606–618. doi:10.1080/00071310020015280. PMID 11140886. S2CID 3913561.

- ^ "The battle for digital privacy Is reshaping the internet". www.bizjournals.com. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Blue, Juanita; Condell, Joan; Lunney, Tom. "A Review of Identity, Identification and Authentication" (PDF). International Journal for Information Security Research. 8 (2): 794–804.

- ^ "What is a digital twin? | IBM". www.ibm.com. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ DeNamur, Loryll (June 17, 2022). "Digital Identity: What is it & What Makes up a Digital Identity? | Jumio". Jumio: End-to-End ID, Identity Verification and AML Solutions. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (July 28, 2006). "Bank Secrecy Act / Anti-Money Laundering Examination Manual" (PDF). www.ffiec.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - 52013PC0045 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. 2013.

- ^ "Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006".

- ^ Affairs, The Department of Internal. "AML/CFT Act and Regulations". www.dia.govt.nz. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Data Exchange Mechanisms and Considerations". enterprisearchitecture.harvard.edu. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Cameron, Kim (May 2005). "The Laws of Identity". msdn.microsoft.com. Microsoft.

- ^ Kahn, Robert; Wilensky, Robert (May 13, 1995). "A Framework for Distributed Digital Object Services". Corporation for National Research Initiatives.

- ^ Cser, Andras (July 17, 2017). "The Forrester Wave™: Risk-Based Authentication, Q3 2017". www.forrester.com. Retrieved June 4, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Clare (2012), "Digital Identity – A New Legal Concept", Digital Identity: An Emergent Legal Concept, Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press, pp. 19–40, doi:10.1017/upo9780980723007.004, ISBN 9780980723007, retrieved May 10, 2023

- ^ "Right to be Informed". General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Art. 83 GDPR – General conditions for imposing administrative fines". General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "What is Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) and How Does It Work?". Security. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "What Is Two-Factor Authentication (2FA)?". Authy. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "What is Certificate-Based Authentication". Yubico. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c "PDF.js viewer" (PDF).

- ^ Higgins, E. T. (1987). "Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect". Psychological Review. 94 (3): 319–340. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319. PMID 3615707.

- ^ Goffman, E. (1959). "The moral career of the mental patient". Psychiatry. 22 (2): 123–142. doi:10.1080/00332747.1959.11023166. PMID 13658281.

- ^ Stryker, S. & Burke, P. J. (2000). "The past, present, and future of an identity theory". Social Psychology Quarterly. 63 (4): 284–297. doi:10.2307/2695840. JSTOR 2695840.

- ^ a b Bay, Jennifer (2010). Body on >body<: Coding subjectivity. In Bradley Dilger and Jeff Rice (Eds.). From A to <A>: Keywords in markup: Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 150–66.

- ^ Marwick, Alice E. "Online Identity" (PDF). tiara.org. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Turkle, S. (1995). "Ghosts in the machine". The Sciences. 35 (6): 36–40. doi:10.1002/j.2326-1951.1995.tb03214.x.

- ^ Chaffer, Tomer Jordi; Goldston, Justin (November 2022). "On the Existential Basis of Self-Sovereign Identity and Soulbound Tokens: An Examination of the "Self" in the Age of Web3". Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Consultation Regulation Impact Statement" (PDF). Digital Identity. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Di Nicola, A. (2022). "Towards digital organized crime and digital sociology of organized crime". Trends in Organized Crime: 1–20. doi:10.1007/s12117-022-09457-y. PMC 9148938. PMID 35669219.

- ^ Sullivan, Clare (2010). Digital Identity. The University of Adelaide. doi:10.1017/UPO9780980723007. ISBN 978-0-9807230-0-7.

- ^ "The vital role to be played by Digital identity and the Legal Entity Identifier in the future of global business". LEI Worldwide. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "What happens to my Facebook account if I pass away | Facebook Help Center". www.facebook.com. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ Macdonald, Ayang (March 14, 2022). "China to introduce digital ID cards nationwide | Biometric Update". www.biometricupdate.com. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (March 16, 2022). "China to roll out digital ID cards nationwide". NFCW. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "On biometric IDs, India is a 'laboratory for the rest of the world'". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Jarrahi, Javad (March 26, 2021). "Iran unveils new e-government components as digital ID importance grows | Biometric Update". www.biometricupdate.com. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Sim, Royston (January 20, 2023). "Singapore to roll out measures to help its people better navigate digital services: Josephine Teo". The Straits Times. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Parsovs, Arnis (March 3, 2021). Estonian electronic identity card and its security challenges (Thesis thesis). University of Tartu.

- ^ "Der Online-Ausweis". Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (in German). Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Ehneß, Susanne (May 4, 2021). "Die "Digitale Identität" löst den Ausweis ab". www.security-insider.de (in German). Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Italy's digital identity system: What is SPID and how do I get it?". Wanted in Rome. November 5, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "Digital identity in Monaco / Identité Numérique / Nationality and residency / Public Services for Individuals- Monaco". en.service-public-particuliers.gouv.mc. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Antoniuk, Daryna (March 30, 2021). "Ukraine makes digital passports legally equivalent to ordinary ones | KyivPost - Ukraine's Global Voice". KyivPost. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine - Ministry of Digital Transformation: Ukraine is the first country in the world to fully legalize digital passports in smartphones". www.kmu.gov.ua. March 30, 2021. Archived from the original on April 3, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Gov.UK Verify: Late, unnecessary and finally launching this week". www.computing.co.uk. May 25, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "Australian Taxation Office defaults agent log in to myGovID from Saturday". ZDNET. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "AIA Australia adapts, then adopts Digital iD via DocuSign". iTnews. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ PYMNTS (September 10, 2021). "Consent-Based Social Security Number Verification Helps to Reduce Synthetic IDs". www.pymnts.com. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "H.R.4258 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Improving Digital Identity Act of 2021 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress". Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "Titles - H.R.4258 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Improving Digital Identity Act of 2021 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress". Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "Actions - H.R.4258 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Improving Digital Identity Act of 2021 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress". Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "US senators introduce bipartisan Improving Digital Identity Act". Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimate: S. 4528, Improving Digital Identity Act of 2022" (PDF). Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "Digital Identity Project | CDT". Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ Kalaf, Eve Hayes de (August 3, 2021). "How some countries are using digital ID to exclude vulnerable people around the world". The Conversation. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "DIACC launches certified trustmark program for Canadian digital ID services". October 18, 2022.

- ^ "The state of Digital ID in Canada". May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Public Sector Profile of the Pan-Canadian Trust Framework (PSP PCTF)". Digital Identity Laboratory of Canada. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ ""Information at your fingertips"- National Digital Identity Project". October 13, 2021.

- ^ "European Digital Identity". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "NIDS Bill still problematic despite being passed in both Houses — JFJ | Loop Jamaica". Loop News. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "One Caribbean digital ID and card announced, another faces political opposition". December 5, 2022.