Wendo Kolosoy

Wendo Kolosoy | |

|---|---|

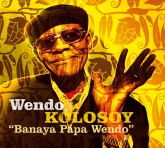

The cover of his last record, Banaya Papa Wendo | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Antoine Kalosoyi (var. Nkolosoy)[1] |

| Also known as | Papa Wendo, Wendo, Windsor, Wendo Sor, Sor, Wendo alanga nzembo, Wendo mokonzi ya nzembo[2] |

| Born | April 25, 1925 Mushie, Mai-Ndombe District, Belgian Congo |

| Origin | Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Died | July 28, 2008 (aged 83) Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Genres | Soukous World Music |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, guitarist, band leader |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitar |

| Years active | 1943–1964/1993–2004 |

Antoine Wendo Kolosoy (April 25, 1925 – July 28, 2008), known as Papa Wendo, was a Congolese musician. He is considered the "doyen" of Congolese rumba, a musical style blending traditional Kongolese rhythm and son cubano.[3][4][5]

Biography

Early life

Wendo was born in 1925 in Mushie territory, Mai-Ndombe District of western Congo, then under Belgian colonial rule. His father died when he was seven, and his mother, a singer herself, died shortly thereafter. He was taken to live in an orphanage run by the Society of the Missionaries of Africa, and remained there until he was 12 or 13, expelled when the fathers disapproved of the lyrics of his songs.[6] Wendo began playing guitar and performing at age 11.[7]

Kolosoy became a professional singer almost by chance after having worked also as a boxer, sailor and longshoreman in Congo, Cameroon and Senegal. From 13 Wendo traveled as a worker on the Congo River ferries, and entertained passengers on the long trips. Between 1941 and 1946 he traveled as a sometime professional boxer, as far from home as Dakar, Senegal.[7]

Stage name

His birthname was Antoine Kalosoyi (also spelled Nkolosoyi), which he eventually regularised to Kolosoy. Later he was called "Windsor" (a homage to the Duke of Windsor and a play on the British Royalty theme of his band "Victoria Kin") which evolved into "Wendo Sor" and simply "Sor". He is most widely known as Wendo or Papa Wendo.[8]

"Father" of Soukous

In the mid-1940s, he began playing guitar around the capital Kinshasa (then Leopoldville) with his Cuban style band Victoria Bakolo Miziki. He had met Nicolas Jéronimidis, a Greek businessman, on a steamer returning to Leopoldville from Dakar in 1946, and in 1947 Jéronimidis agreed to record Wendo's music for his new Leopoldville based record label Ngoma.[9]

Victoria Kin Orchestra

Imitating the bandleader Paul Kamba, Wendo and Me Taureau Bateko created the "Victoria Kin" orchestra, which later became "Victoria Bakolo Miziki", recording for Ngoma, but also other Congolese labels.[10] Fronted by Wendo's echoing and soaring vocals, the group was also famous for its dancers, called "La reine politesse" directed by Germaine Ngongolo.[11]

Wendo and Victoria Bakolo Miziki released their first full record in 1949, "Mabele ya mama" which Wendo dedicated to his late mother.

Marie-Louise

His first international hit, in 1948, was "Marie-Louise", co-written with guitarist Henri Bowane. Through the publicity of "Radio Congolia", along with the controversy which followed the song (a back-and-forth between Wendo and Henri over Wendo's pursuit of a girl, thwarted by Henri's wealth, with salacious undertones),[12] the song became a success throughout West Africa. With its success came trouble: the song had "satanic" powers attributed to it by Catholic religious leaders. Stories from the time even claimed that the song, if played at midnight, could raise the dead. The furor drove Wendo out of Kinshasa, and resulted in a brief imprisonment by the Belgian authorities in Stanleyville and his excommunication from the Catholic Church.[13] The combination of African lyrics and vocals with Afro-Cuban rhythms and instrumentation (particularly son cubano) spawned one of the most successful African musical genres: soukous, popularly known as "Congolese rumba". Wendo's time on the ferries also contributed to his success as one of the first "national" artists of the DRC: he learned the music of the ethnic groups up and down the river, and later sang not only in his native tongue of Kikongo, but also in fluent Lingala and Swahili.[11]

Congolese popular music

Wendo's success rested upon the burgeoning radio stations and record industry of late colonial Leopoldville, which often piped music over loudspeakers into the African quarters, called the "Cite". A handful of African clubs (closing early with a 9:30PM curfew for non-Europeans) like "Congo Bar" provided venues, along with occasional gigs at the upscale white clubs of the European quarter, "La ville". The importation of European and American 78 rpm records into Africa in the 1930s and 1940s (called G.V. Series records) featured much Cuban music, a style that was enjoyed by cosmopolitan Europeans and Africans alike. One writer has argued that this music, sophisticated, based on Africa music, and not produced by white colonialists especially appealed to Africans in general, and newly urban Congolese in particular.[14] Greek and Lebanese merchants, a fixture in colonial Francophone Africa were amongst the first to bring recording and record pressing equipment to tropical Africa. Jéronimidis' "Ngoma" company was one of the first and most successful, and Wendo was his star artist. Jéronimidis, Wendo, and other musicians, barnstormed around Belgian Congo in a brightly painted Ngoma van, performing and selling records. The music culture this created not only propelled Congolese rumba to fame, but began to develop a national culture for the first time.[15]

1950s

In 1955, Wendo, along with two other singer/guitarists (Antoine Bukasa and Manuel D’Oliveira) formed an all-star orchestra known as the "Trio Bow", recording new variations on the rumba and other dance musics for Ngoma, with hits such as "Sango ya bana Ngoma", "Victoria apiki dalapo", "Bibi wangu Madeleine", "Yoka biso ban’Angola", and "Landa bango".[11] Although he never achieved comparable international success similar to that of Papa Wemba or Zaiko Langa Langa, he played throughout Africa, Europe and the USA and is recognized as one of the fathers of modern African music and an elder statesman of Congolese Soukous. In reviewing the recent film on Wendo, a writer in the Kinshasa daily Le Potentiel wrote that "One cannot speak of modern music without evoking the name of Wendo Kolosoy."[16] Soukous musicians who have come after him have referred to the 1940s and 1950s as "Tango ya ba Wendo" ("The Era of Wendo" in Lingala).[17]

50 year hiatus

At the height of his fame, Wendo developed friendships with some of the DRC's future independence leaders, most notably Patrice Lumumba. The murder of Prime Minister Lumumba in 1961, followed by the 1965 seizure of power by Lieutenant General Mobutu Sese Seko, soured Wendo on politics, music, and public life. He decided to stop performing, citing use of music by politicians as his reason.

"Because political men at the time wanted to use musicians like stepping stones. That is to say, they wanted musicians to sing their favors. Me, I did not want to do that. That's why I decided it was best for me, Wendo, to pull myself out of the music scene, and stay home."

When Laurent-Désiré Kabila returned to power in 1997, he (and later his son Joseph Kabila) supported Wendo in restarting his recording and touring career. Performing with old members of his Victoria Bakolo Miziki band and his "Dancing Grannies" backup dancers, Wendo toured across the Africa and Europe, recapturing audiences in a fashion similar to the Buena Vista Social Club and Orchestra Baobab.[19] Original members of Victoria Bakolo Miziki who returned to Wendo's reformed big band included Antoine Moundanda (thumb piano), Joseph Munange (saxophone), Mukubuele Nzoku (guitar), and Alphonse Biolo Batilangandi (trumpet).[20]

Later life

Kolosoy gave his last public appearance in Kinshasa, DR Congo in 2004. The last known recording from that time, the album Banaya Papa Wendo was released on the IglooMondo label in 2007. A compilation called The very best of Congolese Rumba - The Kinshasa-Abidjan Sessions was released in 2007 with Papa Wendo and two other soukous/rumba legends; Antoine Moundanda and the Rumbanella Band. In 2008, prior to his death, French filmmaker Jacques Sarasin released a biographical documentary about Wemba's life, entitled On the Rumba River.[21][22]

He became ill in 2005, and ceased performing publicly. At the time he returned to his disgust with politicians, claiming that the Kabila family, who had resuscitated his career in 1997, had abandoned him financially.[23] Wendo Kolosoy died on July 28, 2008, in Ngaliema Clinic in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[24]

A state funeral in Kinshasa for Wendo is planned, and expected to be "amongst the biggest the city has seen."[25]

Discography

- Nani akolela Wendo? (1993)

- Marie Louise (1997) -- Indigo LBLC 2561 (2001)

- Amba (1999) -- Marimbi 46801.2 (2002) -- World Village 468012 (2003)

- On The Rumba River (Soundtrack) Marabi/Harmonia Mundi 46822.2 (2007)

- Banaya Papa Wendo IglooMondo (2007)

Compilations

- Ngoma: The Early Years, 1948-1960 Popular African Music (1996). Includes the original recording of "Marie-Louise", 1948 (Antoine Kolosoy "Wendo" / Henri Bowane)

- The Very Best of Congolese Rumba - The Kinshasa-Abjijan Sessions (2007) Marabi Productions

- The Rough Guide to Congo Gold—World Music Network 1200 (2008)

- Beginners Guide To Africa—Nascente BX13 (2006)

References

- ^ ANALYSE MUSICALE "Marie Louisa" Antoine WENDO NKOLOSOY. Interview and Review: Norbert MBU MPUTU, Congo Vision (2005)

- ^ "Wendo Kolosoy, 62 ans de carrière musicale" (4 June 2005)

- ^ White, Bob W. (2008-06-27). Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu's Zaire. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8223-4112-3.

- ^ Kisangani, Emizet Francois (2016-11-18). Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 626. ISBN 978-1-4422-7316-0.

- ^ Jelly-Schapiro, Joshua (2016-11-22). Island People: The Caribbean and the World. New York City, New York State, United States: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-34977-2.

- ^ Wendo Kolosoy - On The Rumba River, Artists page: Marabi Records. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ a b Banning Eyre interview (2002)

- ^ "Wendo Kolosoyi". Archived from the original on 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ^ Banning Eyre interview (2002)

"Evolution de la musique congolaise moderne de 1930 à 1950" (2005) - ^ Collector Lars Fredriksson has scans of a late 1940s era catalog from a rival company, ("Olympia"), featuring a sizable set of Victoria Kin records. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ a b c "Wendo Kolosoy, 62 ans de carrière musicale" (2005)

- ^ The Lingala lyrics are transcribed in detail at ANALYSE MUSICALE "Marie Louisa". Norbert Mbu Mputu, Congo Vision (2005) and in brief in Bob W. White (2002)

The song is also analysed in Jesse Samba Wheeler. Rumba Lingala as Colonial Resistance Archived 2009-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, Image & Narrative, No. 10, March 2005 - ^ 'Father' of Congolese rumba dies

"Evolution de la musique congolaise moderne de 1930 à 1950" (2005)

Wendo est mort. A.Vungbo, Le Phare Quotidien (Kinshasa), 2008-07-30 - ^ Bob W. White, Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms (2002)

- ^ Bob W. White, Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms, Cahiers d'études africaines, 168, 2002 details this process, and Gary Stewart's Rumba on the River (1999) is the definitive English language work on these years, which made Kinshasa the musical capital of the continent.

See also the review of the 1996 compilation "Ngoma: the Early Years" at Ntama: Journal of African Music and Popular Culture Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. African Music Archive at Mainz University (1996) - ^ Quoted at Icarus Films.

- ^ Nostalgie bien rythmée. Mia Ma, Jeune Afrique, 4 May 2003

- ^ Wendo Kolosoy interviewed 2002. Banning Eyre, Afropop Worldwide, 2002.

- ^ DR Congo's dancing grannies. Mark Dummett, BBC news. 4 December 2002.

- ^ Icarus Films.

- ^ "Home". rumbariver.com.

- ^ Cinémusique. Renaud de Rochebrune, Jeune Afrique, 11 May 2008.

- ^ "Wendo Kolosoy entre la vie et la mort"(June 2005)

- ^ 'Father' of Congolese rumba dies

- ^ Global Hit: Wendo Kolosoy. The World: PRI/BBC Radio. July 30,

- Wendo's Biography, Music and Videos

- On the Rumba River - A film by Jacques Sarasin

- On the Rumba River: Papa Wendo's Story Archived 2010-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. Village Voice, Julia Wallace. 3 June 2008.

- Wendo Kolosoy interviewed 2002 Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine. Banning Eyre, Afropop Worldwide, 2002.

- Papa Wendo, father of Congolese Rumba dies[permanent dead link]. AFP . 29 July 2008.

- Papa Wendo chante l’idylle du Congo. Olivier Azam, Bakchich.info. 17 May 2008

- Musique: Wendo Kolosoy entre la vie et la mort. Okapi.net/Lp. Le Potentiel (Kinshasa) June 2005.

- Wendo Kalosoy «On The Rumba River». Jeannot ne Nzau Diop. Le Potentiel (Kinshasa), 2007.

- Evolution de la musique congolaise moderne de 1930 à 1950. Jeannot ne Nzau Diop. Le Potentiel (Kinshasa), 14 May 2005.

- Wendo Kolosoy, 62 ans de carrière musicale. Jeannot ne Nzau Diop. Le Potentiel (Kinshasa), 4 June 2005.

- Global Hit: Wendo Kolosoy. Radio broadcast and transcript from The World: Public Radio International//BBC Radio. July 30, 2008. Includes parts of the rare original 78 recording of "Marie-Louise".

- Bob W. White, Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms, Cahiers d'études africaines, 168, 2002.

- Wendo Kolosoy artist profile, label-bleu records, (extracted and translated from Terre de la chanson, la musique congolaise hier et aujourd’hui, by Mpanda Tchebwa, Editions Duculot 1996).

Bibliography

- Gary Stewart (2000). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-368-9.

- 1925 births

- 2008 deaths

- 20th-century guitarists

- 20th-century Democratic Republic of the Congo male singers

- Democratic Republic of the Congo guitarists

- Democratic Republic of the Congo male boxers

- Democratic Republic of the Congo songwriters

- People excommunicated by the Catholic Church

- People from Mai-Ndombe Province

- Soukous musicians

- Label Bleu artists

- Igloo Records artists