Second Battle of Torreón

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (May 2021) |

| Second Battle of Torreón | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mexican Revolution | |||||||

Mexican rebels with cannon | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 18,000 men, with 34 pieces of artillery | 16,550 men, with 24 cannons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,500 | 8,000 | ||||||

The Second Battle of Torreón, which lasted from March 21 to April 2, 1914, was one of the major battles of the Mexican Revolution, where revolutionaries led by Pancho Villa occupied a city protected by Huertist federal forces.

Background

[edit]the first phase of the revolution, which began in 1910, ended with the victory of the revolutionaries: President Porfirio Díaz, who resigned in 1911, was later replaced by the revolutionary Francisco Ignacio Madero. However, in early 1913, with the help of the betrayal of Victoriano Huerta, the followers of the old system murdered Madero, and Huerta became the new president. Against him, a nationwide coalition developed among former revolutionaries, the main commander of the antihuertist movement in Chihuahua was Pancho Villa, although it was Governor Venustiano Carranza of Coahuila who appointed himself commander-in-chief of the entire uprising.

Villa returned to Mexico with only 8 companions from the United States in the spring, but as the months passed, more and more people joined him and acquired more and more weapons. Torreón was once occupied in the fall of 1913, but while fighting later in Chihuahua, government forces regained the city.

After the Battle of Ojinaga, Carranza wanted Villa to attack Torreón as soon as possible, but he asked for time to gather more people, more money, and more weapons.[1] One of the main sources of money, in addition to the sale of cotton and textiles,[2] was the taxation of arcades, horse races, bars and brothels in Ciudad Juárez, but he did not want to profit from the drug trade and even cooperated with the US in the war on drugs.[3] He hoped for more money from the detention of the younger Luis Terrazas: on the one hand, he demanded a ransom for his father, who had fled the state,[4] on the other hand, he heard news that the Terrazas family was hiding high-value property somewhere in the city. The ransom became nothing, but the treasure worth 600,000 pesos was found.[5] On 10 February, the Northern Division's Commercial and Financial Agency, the governing body of the Villista's finances, was also set up under the leadership of Lázaro de la Garza.[6] From the money raised, they bought a lot of weapons and ammunition, new uniforms, and even a two-engine, two-person aircraft, in addition to which two foreign pilots were contracted.[7]

Villa recently formed a personal escort called the Dorados, led by Jesús M. Ríos, and equipped with new, initially oil-green jacket uniforms, 7mm Mauser rifles, and Colt pistols, .44 ammunition.[8]

Meanwhile, the revolutionaries opened a number of recruitment offices and published posters inviting people to join, including even Americans: for them, announcements were made in part in English. Villa also sought good relationships with American physicians: for high salaries, he employed many of them in his newly equipped hospital trains.[9]

Torreón approach

[edit]

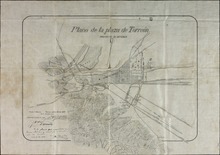

After an old Maderista, Felipe Ángeles, who was an excellent artillery gunner and was highly regarded by Villa, joined the division in mid-March,[10] on March 16 the division set out for Torreón.[11] The army of thousands of people traveled in countless train cars and horses, and more and more people joined them on the way.[12] Horses were also transported inside the carriages, and people were crowded on the roofs, but there were also makeshift kitchens on top of the wagons. They also loaded 29 cannons and 1,700 grenades on the trains.[11] There was a reconnaissance train in front, followed by a train with materials and equipment for rail repairs, then horse-drawn carriages, food wagons, then 40 white-painted hospital wagons, then cannon carriers, and finally passenger cars assigned to infantry and officers.[13]

cut to the north by cutting channels to prevent news of his departure in Ciudad Juarez and the United States, so to the surprise of the government forces stationed in Torreón, who expected the revolutionaries to remain in Chihuahua for another week or two.[11]

They arrived at the Santa Rosalía de Camargo station at 3 a.m. on March 17, where the wedding of one of the Villista leaders, Rosalío Hernández, was held in the city that day, accompanied by a dance party. The next morning, with the brigade of Hernández Leales de Camargo, they set off, arriving in Jiménez at noon. They reached Escalón station at 5 p.m., and a day later, Yermo was destroyed in previous battles. Because the entire countryside was a dry wilderness with no access to water, Villa ordered 12 tankers from Chihuahua for his troops.[13] They arrived at Conejos station at 4 p.m. on March 19.[12]

In addition to the many helpers, medical personnel, and artillery, the brigades numbered more than 8,000. Maclovio Herrera led the 1,300-strong Juárez brigade, Eugenio Aguirre Benavides and Raúl Madero in the 1,500-strong Zaragoza team, Toribio Ortega and González Ortega led 1,200 and Trinidad Rodríguez Cuauhtémoc 400. Máximo García commanded the 400-strong Madero Brigade, Rosalío Hernández Leales de Camargo's team consisted of 600, 1,500 of José Rodríguez's Villa Brigade and 400 or 550 of Miguel González's Guadalupe Victoria Brigade. To this must be added the detachment of about 500 in Durango, as well as Villa's personal escort and staff, some 300 people.[12]

The Nazas Division, under the command of José Refugio Velasco, who defended Torreón, had 7,000 men, 19 cannons and 35 machine guns.[14] Velasco, to prevent a recurrence of the events of last fall, had now assigned troops to a number of locations. He also sent people along the railway to Bermejillo, about 40 km north of the city, Mapimí, 61 km northwest, Tlahualilo in the northeast, and Sacramento, led by Juan Andreu Almazán, to protect the railway line there.[12]

On the March 20, the revolutionary army left Conejos, but Aguirre Benavides separated from them to occupy Tlahualilo. Tomás Urbina, whose men had not yet united with the Villistas, was sent to Mapimí, which he managed to occupy by March 21 despite the outbreak of a smallpox epidemic in his team. Toribio Ortega's forces defeated Benjamín Argumedo's 300-strong unit of the Reds at Estación Peronal, where he ran away from a cavalry attack. Ortega pursued them, but at Bermejillo he encountered another 300 enemies, but they were also smashed, and the rest were persecuted, eventually barely 30 of them escaping. At the same time, Aguirre Benavides also defeated the Tlahualilo allies: he lost 14 people (dead and wounded in total), while about 60 of the Huertists died. The main part of the Northern Division then camped in Bermejillo. Villa also brought together smaller revolutionary troops that were scattered in the area.[15]

Like Velasco, Villa sent troops to Sacramento, led by Aguirre Benavides. Sacramento-defending Almazan gathered his horsemen, the Confederates who had fled Tlahualilo, 200 infantry, and on the afternoon of March 21 a further 600 infantry reinforcement of Colonel Meraz arrived from Monterrey, but they continued on to Torreón. When Almazan saw a huge cloud of dust beaten by the wild riders around 5–6 in the afternoon, he immediately sent a message to Meraz to return, but this did not happen. When the horsemen arrived, melee ensued, and the Confederates soon retreated to the nearby hacienda, where they occupied the buildings and roofs. Since the cannons of Aguirre Benavides and Rodríguez were probably damaged along the way, and many of their dynamite bombs did not work, they had difficulty moving forward through the settlement. Although no reinforcements were requested, Villa sent the Camargo brigade there after receiving the first progress reports. The night attack was repulsed by defenders.[16]

The Battle of Gómez Parramcho and Torreóm

[edit]

On March 22, while the battle of Sacramento was still going on, Villa launched the other men in the direction of Gómez Palacio, adjacent to Torreón. On one of the trains in front, a huge cannon called Niño, which had just been captured in Torreón the previous fall, was placed, followed ide down, examining the road from meter to meter for wires of explosive devices on the rails. Trains could only advance to Santa Clara, 12 km from Gómez Palacio, as the rails were damaged from there. In Santa Clara, Villa allegedly asked some peasants if they had seen “that bandit Pancho Villa” around here. "God Save!" One of them replied.[17]

Meanwhile, the battle was over in Sacramento: the men of Allied Captain Alfonso Durón raised white flags, dropped their weapons, and with exclamations "Long live Villa!" they let everyone know they were moving to the other side. Almazán was forced to give up the settlement and retreat to Torreón. Only 200 people remained, of which only 60 were unharmed.[18]

The villagers approached Gómez Palació in a 5 km wide arc and then got off their horses 4 km from the town. The defenders suddenly fired cannon fire from the hidden corners of the mountains to the revolutionaries, who, among their protégés, launched a cavalry attack on this, and also took the rooky infantry battalions with them. They reached the outskirts of the city, but the defenders' machine guns caused them a lot of damage. Felipe Ángeles could not fire their own cannons, because by this time their own men were already confused with the enemy positions. Eventually, the Villistas managed to occupy the suburbs, albeit at the cost of many dead (35 or 125 according to various sources) and more than 200 injured.[19]

On March 23 around 6 a.m., Ángeles placed the cannons on a small hill called San Ignacio, west of the city. The main base of the Confederates was the Cerro de la Pila in the western part of the city, a few tens of meters high, a little more than 1 km long in the west–east direction, the Cerro de la Pila (with a reservoir at the top) and bases. Also at Casa Redonda, Brittingham Courtyard and the chimneys of La Esperanza Soap Factory.[20]

Villa planned to enclose the enemy, so he sent Herrera to occupy Lerdo, southwest of Gómez Palacio. He was attacked at the entrance to Huarache Canyon by a federal general named Federico Reina with his sword-equipped soldiers, so Villa and his own entourage, Dorados, marched to the scene as a reinforcement, and together they smashed Reina's army, killing the general himself. Complemented by Toribio's Ortega brigade, the revolutionaries occupied Lerdo in the evening, defended by the reds of Benjamín Argumedo. Although the majority of the population sympathized with the Villistas, they did not dare to help them because the Confederates threatened that if they fired a single shot from a house, it would be destroyed along with its residents.[21]

The Cerro de la Pila in Gómez Palació, protected by 500 people and fortified with trenches, machine gun nests and stone-walled walls, however, seemed impregnable to the insurgents. At night, 8 attacks were launched against it, but they were repulsed each time, causing a total of 125 casualties. The only aircraft of the villagers only benefited from reconnaissance, not bombing, as the bombs did not work when dropped from height.[22] On the morning of March 24, Aguirre Benavides and 4,000 men returned from Sacramento, so the revolutionaries were greatly strengthened. The day was at rest, they consulted, rested, and the injured were sent north by train to the hospitals in Chihuahua.[23]

Ángeles said the cannons could only be used effectively if they were deployed much closer to Torreón, so the Cerro de la Pilat had to be occupied by all means. At 3pm on the March 25, a four-hour firefight began, with three shots from Niño hitting the mountain. At 8:45 p.m., 2,000 men from Rodriguez, Urbina, and Herrera launched an attack on the heights, but it was very difficult that before they reached it, they had to cross a large, open area so they could be shot from above. Plenty of them died, and by midnight they had managed to occupy only two of the five small forts established on the mountain. The González Ortega and Guadalupe Victoria brigades also launched an attack on the city along the railway, but the Ortega brigade was unable to evict the Confederates from Casa Blanca, so they had to retreat. In the battles of this day, both sides suffered heavy losses, including the defenders of General Ricardo Peña and the seriously injured General Eduardo Ocaranza.[24]

Meanwhile, the revolutionaries also cleared the area between Gómez Palacio and Lerdo of government forces, and at night more help came from Durango (Severino Ceniceros' people), but even more were expected to arrive soon. At dawn on March 26, the Confederates launched a counterattack and recaptured the two forts lost at night on La Pila. During the day's fighting, José Isabel Robles also arrived from Durango, bringing 1,500 people with them, but they had little ammunition, their clothes were ragged, and not many even had shoes. The railway repairmen, meanwhile, had restored the road so that they could bring the largest cannons closer on the trains, with which they began firing at La Pila again, but fired back at them from there, so they had to retreat. Villa ordered a retreat to El Vergel so he could rearrange the lines there.[25]

On March 26, another attack was launched against La Pila, but they were greeted by silence throughout the city. The Huertists unexpectedly withdrew from Gómez Palacio and joined forces on the other side of the Nazas in Torreón. After several battles, the streets of Gómez Palacio were covered with a multitude of corpses. The exact reasons for the abandonment of the city are still unknown today, it was probably planned earlier that the main clash would take place in Torreón, leaving Gómez Palació only temporarily to exhaust and wear down the Villistas.[26]

At night (and the next day), which dawned from March 26 to 27, Villa telegraphed to the people of Ciudad Juárez, who had played an important role in providing care, asking for clothes and food. Meanwhile, in the Gómez Palace, the winning troops began to plunder, and order was only restored when Villa arrived in town on the morning of March 27. During the day, the revolutionaries sent a message to Torreón asking for the city to be handed over, but the Velascos were optimistic: they believed they would soon receive reinforcements from San Pedro, who would then “chased Villa to Chihuahua,” so the request was denied.[27]

On March 28, the Confederates fired at the mountains surrounding Torreón for 8 hours, but achieved no results with it. The attack of the revolutionaries began at 10 o'clock in the evening, this time the Durango people were sent forward: Carrillo's men to the Calabazas peak, Ceniceroes to the Huarache canyon, and Calixto Contreras to La Polvareda peak. They also won in all three places at night, but Carrillo, despite the order, did not establish defensive positions on Calabazas, his men went to eat and rest, so at 5 a.m. in a counterattack (in which Argumedo's Reds also took part), the Villistas lost two of the three positions. An impromptu court-martial sentenced Carrillo to execution, and Villa left two choices for Carrillo's men: either to take back what they had just lost, or to set them up against a wall and shoot them down.[28]

While Herrera's riders attacked the summit of Santa Rosa, Robles and Aguirre Benavides infiltrated the defenders, infiltrating the city, where they progressed from house to house around the Alameda. Meanwhile, Toribio de los Santos, who had been left to defend Monterrey Road east of the city, clashed with the protector of the federal fortification coming from there. When Villa found out about this, he sent the troops of Ortega and Hernández to help De los Santos. As the revolutionaries who remained at Torreón wanted to prevent reinforcements from getting here, they launched a more intense attack. Villa and Urbina launched an attack towards the city center, but ran away due to machine gun shots. At 3 p.m., they lost Calabazas Peak again, and at 4 p.m., they headed for La Cruz Peak. From 9 pm there was peace on the battlefield.[29]

On the morning of March 30, fighting resumed, this time around the hospital, at Huarache Canyon and La Polvareda, which once again came into the possession of the insurgents. Once in the afternoon, however, there was another brief ceasefire, with Velasco H. Cunnard initiating talks with the attackers through British Vice Consul and US Ambassador George Carothers. They were asked for a 48-hour ceasefire, during which they could gather the dead to prevent a possible epidemic, but the Villistas also refused, because they believed it was only a matter of time to get federal troops from there in the meantime. So after a few hours, the shootings resumed. In the afternoon, 300 federal surrendered in Calabazas and were asked to be led in front of Villa, but Carrillo still shot them, leaving only 50 to arrive at Gómez Palacio. The news came at night that Chihuahua Governor Manuel Chao was sending a thousand people to the revolutionaries because he did not need such forces locally.[30]

March 31 was a relatively quiet day, with many resting, although Argumedo and Robles’ teams were still fighting. A train full of supplies left Ciudad Juárez for the battlefield. The next day, a large team of defenders wanted to break out of the ring around them on the side of La Fortuna Mountain, but they were shot by the revolutionaries, so their attempt failed. It was then that news came that De los Santos had arrested the Confederates from the East, while Chao's Chihuahua revolutionaries had arrived, giving the attackers a significant advantage. Villa stopped Carrillo's execution, but in return instructed Carrillo's men to try to reclaim the lost positions again. Others attacked the city center and Huarache Canyon again.[31]

Around 2 a.m. on April 2, Miguel González recaptured Calabazas (although this was lost again three hours later), Eladio Contreras and La Polvareda, and then two barracks in the city fell into the hands of revolutionaries. In the morning, the Huertists attacked Mount Santa Rosa, but it was defended by Colonel Mateo Almanza of the Morelos Brigade.[32]

The past day was the bloodiest in two weeks of fighting, but the Confederates, in addition to plenty of dead, began to have trouble with ammunition: only one-eighth of their original 2 million ammunition remained. This also helped them decide to flee towards Viesca with their remaining 4,000 people at four in the afternoon. The news that the Confederates were leaving the city only became apparent in the evening. However, Villa and his armies were exhausted, so they did not follow in their footsteps, glad to finally catch their breath.[33]

According to Alberto Calzadíaz, 1,781 of the revolutionaries lost their lives to 1,937 wounded (he reported 1,500 wounded to Villa and Carranza), and a total of 8,000 of the Confederates claimed to have been killed or injured, captured or left the army. The losers left 400 seriously injured in Torreón, healed by the Villistas. Although some captive officers were still shot dead, this time far fewer than in previous battles.[34]

Mutual Film, which had a contract with the Villistas, also tried to film during the Battle of Torreón, but the footage was ruined and some of them had to be re-filmed later in the United States by replaying the events. It is a widespread legend that Villa postponed an attack originally planned for the night to the day for the sake of the filmmakers, but this was probably not the case in reality.[35]

Aftermath

[edit]When Villa arrived in town at 9 a.m. on April 3, he was greeted by a real folk festival. It is likely that his decree (as he was famous for his teetotalism) was overtaken the next day by calls from Comarca Lagunera towns forbidding the consumption of alcoholic beverages, and those who violated it would be shot without warning.[34] He also announced that whoever did not clean their house inside and out and the street in front of their house will be fined 100 pesos.[35] They also captured the Spanish population of the city (with a few exceptions) and first locked them in a cellar and then crammed them into 5 wagons and started them towards the northern border. The reason for this was, on the one hand, that most of them supported Huerta in the fight, and, on the other hand, he learned that their employees were paid extremely low wages, and this also outraged him. Two months later, he released those who did not support the government and admitted that there were injustices against them, but excused himself that all this took place in a war situation.[36]

The battle also wreaked havoc in the city,[34] and the spoils of war were not significant either, because what the refugees did not take was burned. However, much of the cotton that Villa sent north to sell remained,[37] and used to distribute bread, corn, and beans to the people of Torreón, among other things.[35] He also bought flour, salt, a wagon of fat, 27,624 pairs of boots and 2,500 hats. Its additional revenue came from the taxation of the newly opened arcades in Torreón.[37]

After the Battle of Torreón, another major clash took place between the federal army, which gathered in San Pedro de las Colonias, numbering just over 10,000, and no less than 22 generals in its ranks,[38] and the Villistas: the 12-16 thousand revolutionaries[39] defeated the government forces on 14 April, the remaining ones left for Saltillo.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 279.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 294.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 281.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 277.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 282.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 296.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 280.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 306.

- ^ a b c Taibo 2007, p. 308.

- ^ a b c d Taibo 2007, p. 310.

- ^ a b Taibo 2007, p. 309.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 312.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 311.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 313.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 315.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 319.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 322.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 324.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 327.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 328.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 331.

- ^ a b c Taibo 2007, p. 332.

- ^ a b c Taibo 2007, p. 334.

- ^ Taibo 2007, pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b Taibo 2007, p. 333.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 342.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 344.

- ^ Taibo 2007, p. 343.

Bibliography

[edit]- Taibo, Paco Ignacio (2007). Pancho Villa: Una biografía narrativa (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Barcelona: Editorial Planeta. ISBN 9788408073147. OCLC 433362298.

- Ramírez Rancaño, Mario (2005). "La república castrense de Victoriano Huerta" (PDF). Estudios de historia moderna y contemporánea de México (in Spanish) (30): 199–200. ISSN 0185-2620. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)