Letters Patent, 1947

| Part of a series on the |

| Constitution of Canada |

|---|

|

|

|

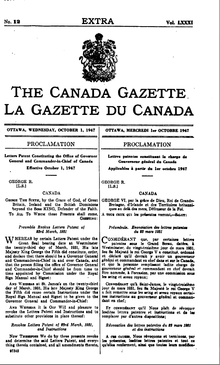

The Letters Patent, 1947 (formally, the Letters Patent Constituting the Office of Governor General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada), are letters patent signed by George VI, as King of Canada, on 8 September 1947 and came into effect on 1 October of the same year. These letters, replacing the previous letters patent issued in 1931, reconstituted the Office of the Governor General of Canada under the terms of the Constitution Act, 1867, expanding the governor general's ability to exercise the royal prerogative, thereby allowing her or him to use most of the "powers and authorities" lawfully belonging to the sovereign[5] and to carry out an increased number of the sovereign's duties in "exceptional circumstances".[6]

While the Crown theoretically has the power to revoke or alter the letters patent at will, it remains unclear to what extent that power remains after the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982, which requires all changes to the office of the King and the governor general to be done through a constitutional amendment approved by Parliament and all provincial legislatures.[7][8]

Historical context

The first letters patent in Canada were, starting in 1663, issued to the governors of New France by the kings of France.[9] At that time, the letters patent outlining the office of the governor and its role were issued with a commission appointing the occupant to the office, as well as an accompanying set of royal instructions. In this way, a different set of letters patent were issued by the Crown each time a new governor was appointed, a custom that was continued by the British following the surrender of New France to the United Kingdom in 1763. This system remained largely unchanged until 1947, with two exceptions: The first was the granting of the title commander-in-chief in 1905 and the second occurred in 1931, under the Statute of Westminster, when the governor general went from acting as an agent of the British government (the king in his British council or parliament) to a representative of the Canadian Crown.[10]

The experiences of the Kingdom of Iceland during the Second World War also gave Prime Minister Louis St Laurent an example of how the lack of a regency act or similar mechanism could, in certain circumstances, provoke a constitutional crisis. When Denmark was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1940, Iceland found itself in the peculiar position wherein its king, Christian X, who was also king of, and resided in, Denmark, was cut off from Iceland and unable to perform his constitutional duties for that country, such as granting royal assent to bills and exercising the royal prerogative. With no method to allow for the incapacity of the sovereign, the Icelandic parliament was forced into passing an illegal constitutional amendment and appointing Sveinn Björnsson as regent.[11]

The subject of the Canadian governor general's ability to act in the absence or incapacitation of the monarch was discussed in the House of Commons in 1947. This brought up Canada's lack of something similar to the United Kingdom's Regency Act, which further underscored the need for such a mechanism within the Canadian political structure. As a result, the 1947 letters patent were issued by King George VI later that year, allowing the governor general to carry out nearly all of the sovereign's duties in case of the monarch's capture or incapacity and, thus, negating the need for His Majesty's Canadian government to go through the process of passing legislation equivalent to the Regency Act.[10]

Implementation

The intent behind the Letters Patent, 1947, was to re-draft the 1931 letters patent into a uniquely Canadian document empowering the governor general by way of "enabling legislation".[12] At the time, it was remarked that "there seems to be no change in the status of governor general" and that the governor general "still remains an officer to whom His Majesty has committed extensive but definite powers and functions."[13] Prime Minister Mackenzie King wrote to the King, stating that, "unless exceptional circumstances made it necessary to do so, it was not proposed by the Canadian government to alter existing practices without prior consultation or notification to the governor general and the King".[14] Consequently, despite the permissions in the Letters Patent, 1947, there is no legal impediment to the King exercising any of his powers himself;[15] the Canadian sovereign continues to wield "[his] prerogative powers in relation to Canada concurrently with the governor general."[15] As a matter of law, the governor general of Canada is not in the same constitutional position as the sovereign.[15] Even many years after the implementation of the letters patent, a variety of matters continue to be submitted exclusively to the sovereign, such as the creation of honours, the appointment of governors general, and authorizing declarations of war.[16] Other matters, such as the approval of Canadian ambassadors to and from foreign countries and the signing of treaties, have since been delegated entirely to the governor general.[20]

Unlike other parts of the constitution, the letters patent are a creation of the monarch's royal prerogative and cannot be repealed by Parliament.[21] Conversely, the Letters Patent, 1947, would not be sufficient to effect such a dramatic change as a transfer of power from the King to the governor general, as any changes to the role of both of these positions are subject to the amending formula provided in section 41 of the Constitution Act, 1982,[22] which requires alterations to the office of the King and the governor general be done through a constitutional amendment approved by Parliament and all the provincial legislatures. For example, the permission in the letters patent for the governor general to exercise the role of commander-in-chief cannot be construed as an abdication of this duty by the king, as the position is constitutionally vested in the monarch and any changes to that arrangement would require an amendment of section 15 of the Constitution Act, 1867.[23][24]

Theoretically, the King can revoke,[15] alter, or amend the 1947 letters patent. However, the interaction between the King's powers to revoke or alter letters patent and the Constitution Act, 1982, remains unclear.[8]

Impact

While the role of the governor general is largely considered a ceremonial one, the powers of the Crown that the Letters Patent, 1947, permitted the Office of the Governor General to use are substantial. Increased attention is sometimes brought to these powers by political events, such as the 2008 and 2009 prorogations of the federal Parliament, which serve to increasingly highlight the role that the governor general plays within the Canadian constitution.[25] Even though the monarch's permission to use the powers put the governor general "not in quite the same position as the sovereign in regard to the exercise of certain prerogative powers",[26] the 1947 letters patent serve to allow the Canadian political system a greater amount of flexibility in the exercise of the Canadian Crown's powers.

Misconceptions

The letters patent of 1947 have been misconstrued as effecting a transfer of all the powers of the Crown to the governor general and, thus, putting the governor general in a position equal to that of the King. Even former governors general have failed to grasp the essence of the letters patent.[7] Former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson expressed in her memoirs that, "many politicians don't seem to know that the final authority of the state was transferred from the monarch to the governor general in the letters patent of 1947",[27] a statement determined to be "nonsense on Clarkson’s part" and where her referring to herself as a "head of state" simply reinforced her "misunderstanding of the letters patent."[7] In 2009, Michaëlle Jean also stated that she was Canada's head of state, which led to a rare public rebuke from the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, who stated "categorically" that Queen Elizabeth II was Canada's head of state and that the governor general served as the Queen's representative in Canada.[28] It is apparent from political correspondence of the time that it was never the belief of the government that such powers had ever been transferred.[13][16][29] In addition, the tabling, in 1978, of Bill C-60, which moved to legally transfer the powers exercised by the Queen to the governor general, would have been completely redundant if such a transfer had already occurred 31 years previous.[29][30]

References

- ^ Office of the Governor General of Canada. "The Governor General > Role and Responsibilities". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage (24 September 2014). "The Crown". Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage (2 October 2014). "Governor General Ceremonies". Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Government of Canada (2 October 2014). "The Governor General". Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ [1][2][3][4]

- ^ King, William Lyon Mackenzie (5 May 1947). Letter to Sir Alan Lascelles from Prime Minister Mackenzie King. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ a b c Romaniuk, Scott Nicholas; Wasylciw, Joshua K. (February 2015). "Canada's Evolving Crown: From a British Crown to a "Crown of Maples"". American, British and Canadian Studies Journal. 23 (1): 116. doi:10.1515/abcsj-2014-0030.

- ^ a b Harris, Carolyn (15 March 2016). "Letters Patent, 1947 | The Canadian Encyclopedia". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

The monarch may theoretically revoke the Letters Patent at any time, but section 41(a) of the Constitution Act, 1982 requires the approval of provinces and the federal government for changes to the office of the King, which has the potential to impact changes to the Letters Patent.

- ^ Eccles, W.J. (1964). Canada Under Louis XIV, 1633-1701. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. p. 27.

- ^ a b McCreery, Christopher (2012), "Myth and Misunderstanding: The Origins and Meaning of the Letters Patent Constituting the Office of the Governor General, 1947", The Evolving Canadian Crown, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, pp. 38–52, ISBN 978-1-55339-202-6

- ^ Lacey, T.G. (1998). Rising of Seasons: Iceland - Its Culture and History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 130.

- ^ Her Majesty's Privy Council Office (2010). Manual of Official Procedure of the Government of Canada. Ottawa: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. p. 140.

- ^ a b MacKenzie King, W.L.; Schuster, W.P. (1948). "The Office of Governor-General in Canada". University of Toronto Law Journal. 7 (2): 474–483. doi:10.2307/823834. JSTOR 823834.

- ^ William Lyon Mackenzie King (1947). Letter to Sir Alan Lascelles, Private Secretary to the King from W.L. Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, 7 August 1947. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ a b c d Walters, Mark D. (2011). "The Law behind the Conventions of the Constitution: Reassessing the Prorogation Debate" (PDF). Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law. 5: 131–154. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ a b Gotlieb, A.E. (1965). Letter to A.S. Miller, Privy Council Office from A.E. Gotlieb, Department of Foreign Affairs, 29 November 1965. Ottawa: Privy Council Office Archives.

- ^ Aimers, John, "Martin Government Removes Queen From Diplomatic Documents" (PDF), Canadian Monarchist News, Spring 2005 (23), Monarchist League of Canada, retrieved 2 February 2023

- ^ Government of Canada, "5", Policy on Tabling of Treaties in Parliament, Queen's Printer for Canada, retrieved 2 February 2023

- ^ Barnett, Laura (1 April 2021), "Canada's Approach to the Treaty-Making Process" (PDF), Hill Studies (2008–45–E), Ottawa: Library of Parliament, retrieved 2 February 2023

- ^ [17][18][19]

- ^ Donovan, Davis S. (27 May 2009), The Governor General and Lieutenant Governors: Canada's Misunderstood Viceroys (PDF), Canadian Political Science Association, p. 5, retrieved 22 October 2012

- ^ "Constitution Act, 1982". Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. 17 April 1982. p. s.41. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Heard, Andrew (1990). "Independence". Simon Fraser University. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "Constitution Act, 1867". Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. 29 March 1867. p. s.15. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Patrick Monahan (June 2010). Smith, Jennifer; Jackson, Michael D. (eds.). The Constitutional Role of the Governor General. State of the Federation Conference. West Block, Parliament of Canada, Ottawa: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, School of Policy Studies, Queen's University.

- ^ Dawson, R.M. (1948). The Government of Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Clarkson, Adrienne (2006). Heart Matters. Toronto: Viking Canada. p. 190.

- ^ Franks, C.E.S. (23 August 2012). "Keep the Queen and choose another head of state". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ a b Smith, David E. (May 1999). "Republican Tendencies" (PDF). Policy Options: 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2012.

- ^ "History". Citizens for a Canadian Republic. 23 April 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2012.