Battle of Fayetteville (1862)

| Battle of Fayetteville (1862 Western Virginia) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kanawha Valley Campaign of 1862 of the American Civil War | |||||||

Fayette County, West Virginia (Fayette County was part of Virginia in 1862). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Edward Siber | William W. Loring | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

District of the Kanawha

|

Dept. of SW Virginia

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 1,200 | ~ 5,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

139

|

88

| ||||||

| Mortally wounded have been removed from wounded counts and added to those killed. | |||||||

The Battle of Fayetteville occurred in Fayette County, Virginia (now West Virginia), on September 10, 1862, during the American Civil War. A Confederate army, consisting of multiple brigades commanded by Major General William W. Loring, drove away a Union brigade commanded by Colonel Edward Siber. The battle is part of the Kanawha Valley Campaign of 1862.

During August 1862, Union Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox was ordered to move his Kanawha Division from southwestern Virginia to Washington as reinforcement for Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia. Cox left behind a small force of about 5,000 men, which was under the command of Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn. Confederate leadership found out about the depleted force, and sent Loring to drive the remaining Union soldiers out of the Kanawha Valley. Loring had a force of about 5,000 men, but some people believed his force numbered as many as 10,000.

Lightburn's troops were divided into two brigades. His First Brigade, commanded by Colonel Siber, was stationed at Fayetteville, which put it between the Kanawha Valley and Loring. The Battle of Fayetteville was the first battle in Loring's attempt to accomplish his objective of clearing the Kanawha Valley, and his force was about four times the size of Siber's—although Siber's men had the protection of fortifications. Lightburn's other brigade was further north and not involved in the battle. Loring moved one brigade to Siber's right flank, while another made a frontal attack. Siber held off Loring for the whole day, but realized he was nearly surrounded. After midnight, Siber's force escaped north to the Kanawha River. Loring pursued, beginning a series of skirmishes that led to the Battle of Charleston.

Background

The Commonwealth of Virginia ratified an Ordinance of Secession that declared secession from the United States on May 23, 1861, and later joined other southern states in the Confederate States of America.[1] Many people in the western portion of Virginia preferred to remain loyal to the United States ("the Union"), and they declared their own statehood on October 24, 1861—but did not officially become the state of West Virginia until June 20, 1863.[2][3] Loyalties were mixed in the southern half of western Virginia (including the Kanawha Valley), with many of the people from the mountains being pro-Union, while the majority in the large valleys were pro-Confederate.[4]

The American Civil War began in 1861, and Union forces gained control of a large portion of southwestern Virginia, including the Kanawha Valley. The Kanawha River is formed by the meeting of the New River and the Gauley River at the community of Gauley Bridge in Fayette County.[5] Among the communities occupied by Union troops beginning in November 1861 was Fayetteville, county seat of Fayette County.[6][Note 1] At least three fortifications were built around Fayetteville during late 1861 and early 1862.[8]

The region had rugged terrain, few settlements, and few good roads.[9] Along the north side of the New and Kanawha rivers, the James River and Kanawha Turnpike ran from east of the Allegheny Mountains to Gauley Bridge and Charleston.[10] From a point on the Kanawha River about 10 miles (16 km) upstream from Charleston, small steamboats could be used to navigate to the Ohio River, meaning the river and turnpike could be used to transport troops and supplies.[11] Fayetteville had strategic significance because it was also situated on one of the few good roads. The Giles, Fayette, and Kanawha Turnpike ran from Pearisburg, Virginia, to Fayetteville and the Kanawha River.[6]

Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox was commander of the Union Kanawha Division that controlled southwestern Virginia along the Kanawha River Valley.[12][Note 2] On August 14, 1862, Cox began moving his Kanawha Division to Washington as reinforcement for Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia.[14] Exceptions to Cox's orders were about 5,000 troops left behind and put under the command of Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn, who was headquartered at Gauley Bridge.[15] Soon after Cox left the Kanawha Valley, Pope's quartermaster was captured along with numerous records, and Confederate leaders learned that Cox had left only 5,000 men in the Kanawha Valley.[16] Most of the Union troops in the region were stationed at posts surrounding the community of Gauley Bridge, which was located at the eastern-most point of the Kanawha Valley.[17] Major General William W. Loring was stationed near Pearisburg.[18] He was ordered to move north and clear the Kanawha Valley of Union soldiers, and then move northeast to form a junction with more Confederate soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley.[16]

Opposing forces

Union army

Colonel Edward Siber, of the 37th Ohio Infantry Regiment, commanded the 1st Brigade.[19] Siber had over 20 years of service as a German soldier in Prussia and Brazil.[20] Siber's immediate superior, Colonel Lightburn, was not at the site of the battle.[21] In the battle, Siber's command consisted of:

- 34th Ohio Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel John T. Toland.[22] The regiment was organized by Colonel Abram S. Piatt, who resigned in 1862 after he was injured from a fall from his horse. The men wore distinctive zouave–styled uniforms in blue trimmed with red, and were known as "Piatt's Zouaves".[23] The regiment was considered rough and ruthless. Toland was not well-versed in military procedures, but he was fierce and brave.[22] Lieutenant Colonel Freeman E. Franklin commanded a detachment during the battle.[24]

- 37th Ohio Infantry Regiment, consisting primarily of German immigrants and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Louis von Blessing when Siber was commanding the brigade.[22] Captain William Weste, from Company C, commanded Siber's artillery, which consisted of four mountain howitzers and two smoothbore field pieces.[8][Note 3] During May, the regiment fought in the Battle of Princeton Court House.[26]

During the battle, Colonel Lightburn sent two detachments to assist Siber:

- Three companies of the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry, commanded by Captain John L. Vance.[27]

- Twenty-five men from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Major John J. Hoffman.[28][Note 4]

Confederate army

Major General William W. Loring commanded the Department of Southwestern Virginia.[19] He also used the term "Department of Western Virginia", and called his command the "Army of Western Virginia".[30] He had been a soldier since the age of 14, was a sergeant at the age of 17, and fought in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican–American War.[31] Under his command for the Battle of Fayetteville were:

- The Second Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General John S. "Cerro Gordo" Williams.[32] He was a Mexican-American War veteran, and he earned his nickname for heroics at Cerro Gordo.[33] Under his command were the 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Edgar's Battalion) and the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment.[34] For this battle, the 36th Virginia Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel John McCausland, was part of Williams' brigade.[34]

- The Third Brigade was commanded by Colonel Gabriel C. Wharton.[35] Normally, his command consisted of the 51st Virginia Infantry Regiment and the 30th Virginia Sharpshooters Battalion (a.k.a. Clarke's Battalion of Sharpshooters).[36] In this battle, his command also included the 22nd Virginia Infantry Regiment detached from the Second Brigade and the 23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Derrick's Battalion) detached from the First Brigade.[37][Note 5]

- A cavalry detachment was commanded by Major Logan H.N. Salyer. It included at least three companies normally part of a battalion commanded by William Henderson French, and may have been assisted by Thurmond's Partisan Rangers.[39] Although the three companies were part of the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, they later became part of the 17th Virginia Cavalry Regiment.[40]

- King's Artillery Battalion (13th Battalion, Virginia Light Artillery) provided artillery support.[41] The battalion was led by Major John Floyd King. It consisted of Bryan's, Chapman's, Lowry's, Otey's, and Stamps' batteries of Virginia Light Artillery.[42] During the campaign, various batteries were usually assigned to a brigade. Usually, Otey's and Stamps' batteries were assigned to Williams, Chapman's to Wharton, and Echols used Bryan's and Lowry's batteries.[43] Each battery had two to five artillery pieces.[44]

- The First Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General John Echols. It consisted of the 50th and 63rd Virginia Infantry regiments for this battle.[41] This brigade arrived at the battlefield late, and did not participate in significant fighting—although some of its artillery was used.[45] It was involved in the pursuit afterwards.[46]

Loring moves north

Confederate Major General Loring planned to take control of the Kanawha River Valley by leading a large force in an assault of Union forces located upriver in Raleigh, Fayette, and Kanawha counties. Part of his plan included sending a cavalry force on a semicircular route through 500 miles (800 km) of Union–controlled territory to cut off the Union route of retreat down the Kanawha River.[47] On August 22, he began the execution of his plan by sending north a cavalry force commanded by Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins.[48] As early as August 31, Lightburn had received reports that Loring was at Lewisburg (he was actually further south) with a force of 10,000 troops.[49] Loring's force actually consisted of about 5,000 men instead the rumored 10,000, but he expected to add to it by recruiting and organizing existing local militias.[16][Note 6]

The news of Loring's large force in the south, plus the possibility of Confederate cavalry between Lightburn and Ohio, reached Union camps in early September. At that time, Lightburn consolidated his troops and sent a portion of a cavalry regiment, and several companies of infantry, to find the Confederate cavalry.[51] Siber's brigade was stationed at Raleigh Courthouse (a.k.a. Beckley), and he followed Lightburn's orders to move north to Fayetteville. He began sending companies north on September 4.[52] A portion of Jenkins' Confederate cavalry force was in Ohio on September 4.[53] It returned to Virginia on the next day, reunited with a detachment, and arrived at the small Kanawha River community of Buffalo that evening. Lightburn was aware of Jenkins, but he was not sure of the Confederate cavalry's exact location.[54]

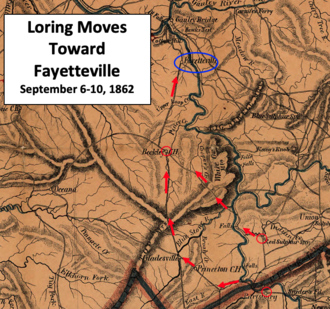

Loring began his advance on September 6, and this is considered the beginning of the Kanawha Valley Campaign of 1862.[19] The brigades of Williams and McCausland departed from Red Sulphur Springs, while Wharton's brigade began the advance in Grey Sulphur Springs. Those two starting points were in Monroe County. Echols' brigade started further south in "the Narrows" of Giles County, Virginia.[55] The distance from the Narrows to Fayetteville is approximately 75 miles (121 km) over mountainous terrain.[56] The Confederate troops moved in two columns, with one west of the New River and one to the east.[57] The eastern column crossed the New River at Pack's Ferry.[58] On September 9, the two columns joined just southeast of Raleigh Court House (a.k.a. Beckley).[57][Note 7] That evening, they camped at McCoy's Mill (now Glen Jean, West Virginia), which was about nine miles (14 km) south of Siber's 1,200-man brigade at Fayetteville.[60]

Loring sent a detachment of cavalry through the woods to Cotton Hill, which was behind (north of) the Union army at Fayetteville.[61] The detachment was from the cavalry battalion of Major Salyers, and it moved northwest until it came to Laurel Creek. Moving east down the creek, they cut telegraph wires at the point where the creek is crossed by the turnpike.[62] Wharton's Brigade, with the 22nd Virginia Infantry detached from Williams' Brigade, took a mountainous path west around Fayetteville to prepare for the flanking and rear attack. The remaining portion of Loring's army, led by William's Brigade, would make a frontal attack via the Princeton-Raleigh Road.[63]

Battle

Troops move into positions

Further up the road from Loring was Siber's brigade in Fayetteville. Siber's brigade consisted of the 34th and 37th Ohio infantry regiments, supported by six artillery pieces. Fortifications on three hills had been built during the previous winter, and Siber used them to defend his position.[8] Siber was worried about his right flank, and sent two companies from the 34th Ohio Infantry to Cassidy's Mill on Laurel Creek. These companies were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Freeman Franklin. Two more companies from the same regiment were sent to join Franklin after taking a different route. Wagon trains began moving supplies from Fayetteville to Gauley Bridge via Montgomery Ferry, and three companies from the 37th Ohio Infantry were sent south to reinforce pickets on the turnpike to Raleigh Court House.[24]

Around noon, Siber sent two companies from the 37th Ohio Infantry on a reconnaissance mission south on the road to Raleigh. About three miles (4.8 km) south of Fayetteville, the two Union companies ambushed Williams' advance guard—which consisted of Company B from the 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion. Although the Confederates drove the Union force back, they realized the Union recon force outnumbered them and withdrew to a wooded area to wait for reinforcements.[63]

Williams advanced the brigade another two miles (3.2 km), and Union forces attacked again at 2:00 pm.[64] This time, the Confederate advance, led by the 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion and the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment, was temporarily stopped. Two Confederate artillery pieces were deployed, causing the Union soldiers to withdraw. Siber then called all troops back to the fortifications.[64] All of the Union fighters on this side of the battlefield were from the 37th Ohio Infantry.[65] However, three companies from the regiment, sent out hours earlier to reinforce pickets, were cut off from Fayetteville. They moved through the woods toward the New River, and did not return in time to fight in the battle.[24] During this time, Lightburn ordered three companies of the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry to move from Gauley Bridge to support Siber at Fayetteville.[27]

Wharton's flanking brigade make contact with Siber around 2:15 pm. It had marched about 13 miles (21 km) over rough terrain, and was scattered and exhausted.[65] It arrived at Siber's right flank, but not behind him, and discovered Siber's artillery was well placed. Wharton decided to re-position his force so that it could cut off Siber's route of retreat along the pike north to Montgomery's Ferry.[66] His troops were placed parallel to the Kanawha–Fayette Pike, but did not expose themselves by being on the pike.[38]

Frontal attack

Two hills were between Williams' Confederates and Siber's Union soldiers. Williams sent four artillery pieces to the first hill, with Edgar's Battalion behind them. The 36th and 45th Virginia Infantry regiments were sent to Siber's right under the cover of woods. Both sides exchanged artillery fire. A 24 pounder howitzer, which had been brought forward earlier at double-quick pace from Echols' Brigade, was added to the artillery pieces on the hill.[45]

The first hill was about 550 yards (500 m) from the Union fortification, and Williams realized the distance was too far for effective firing. He ordered Edgar's Battalion to take the next hill and remain as artillery support.[67] Once the battalion was on the next hill, the artillery pieces moved up and joined them. This put them 300 yards (270 m) from the Union fortification, and the firing became more intense. During this time the 45th Virginia Infantry took casualties as part of the regiment was a diversion on the first hill, while the other portion of the regiment moved through the woods close to the other hill and about 100 yards (91 m) from the Union fortification.[68]

Union right and rear

The Union right and rear was protected by six companies from the 34th Ohio Infantry, and it used a howitzer to attack the Confederate flanking force before it had finalized its deployment in the woods. Concerned about being surrounded, Siber ordered Colonel John Toland to clear the road to Gauley and drive the enemy away from the woods along the road. This task was begun by two companies, led by Captain Henry C. Hatfield, who protected the supply wagons on the road. The other four companies were led by Toland himself, and they attacked the Confederates at the top of a steep hill.[69] Fighting in the open while the enemy was protected by the woods, the Union soldiers loaded their weapons while lying on the ground.[70]

The 51st Virginia Infantry provided much of the defense for the Confederates. Fighting continued for about 90 minutes before the Union companies withdrew to the east side of the road and relied more on their howitzers. After a total of three hours of fighting, the Confederate force was forced to conserve scarce ammunition.[70] Eventually Toland's men drove the Confederates off the hill, but the cost was high.[71] Hatfield was mortally wounded.[69] Toland was not injured, but had two horses shot from under him. Every company from the 350-man force of the 34th Ohio had casualties, and they totaled to roughly one third of Toland's partial regiment.[71][Note 8] Fighting ended shortly after dusk.[73]

Reinforcements arrive

Captain Vance reported to Colonel Siber when the reinforcements arrived at Fayetteville. Siber thanked him, and asked about the number of men and related questions. One of Vance's responses was "We had not been fired upon". This surprised Siber, who noted that "We are surrounded".

The Confederate frontal attack included at least five charges across open fields against the fortified Union soldiers of the 37th Ohio Infantry. All of these charges were repulsed.[75] Just after sunset, the 37th Ohio counterattacked with bayonets and drove Williams' Confederate brigade back. This is thought to be the only bayonet charge ever carried out in Fayette County.[73] Outside of the battlefield, at 3:00 pm Lightburn had ordered his Second Brigade to concentrate at Gauley Bridge—but be ready to retreat if necessary. Five companies of the 47th Ohio Infantry Regiment were sent across the river to Cotton Mountain, where they could offer assistance if Siber needed to retreat.[75]

Lightburn also sent three companies from the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry, and a small detachment from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry, to reinforce Siber.[76] The detachment of companies from the 4th West Virginia Infantry, led by Captain John L. Vance, arrived just after sunset. About the same time, Freeman's Laurel Creek detachment also returned—adding four more companies to Siber's force at Fayetteville. The 25-man detachment from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Major John J. Hoffman, arrived around 8:00 pm. An hour later, all fighting ended, and both armies were in the same positions they had been since late afternoon.[77]

Siber withdraws

At Siber's front, the Confederate brigades commanded by Williams and Echols rested with their weapons nearby.[36] Two pieces of siege artillery were being readied to use on the forward fortification.[78] Loring planned to resume the frontal attack on the next day.[79] At Siber's rear, Wharton's brigade was extremely low on ammunition, and waited for its supply to be replenished.[80] Further north, the small Confederate cavalry force originally sent to cut communications had fled Cotton Hill because of Union infantry arriving in the area. The cavalrymen were cut off from their return route up Laurel Creek, and took a long route through the woods to return to Williams and Loring at the front.[73]

Later in the night, Siber considered withdrawing via a small road that led to the New River. His men could then march to Gauley Bridge on the east side of the river. This idea was rejected because the road was too small and crossing the river would be difficult without any watercraft.[81] Late that evening, Hoffman's cavalry was sent to Loup Creek to block and guard roads that led to the Kanawha River.[79] Between 1:00 and 2:00 am on September 11, Siber began to withdraw using the Cotton Hill route to the Kanawha River that had been used by Captain Vance hours earlier.[82] Vance led the retreat for the first two miles (3.2 km), observing a few Confederate soldiers but no shooting. Vance's detachment then waited on Siber's entire force and became the rearguard.[80] Leaving Fayetteville, the Union force had only one small skirmish as it headed north to Cotton Hill. This perplexed the Union soldiers, since they were not aware of the Confederate ammunition situation.[78]

Aftermath

During the morning of September 11, Williams discovered that the Union army had left Fayetteville. He began a pursuit almost immediately, but was slowed by trees that the Union soldiers had chopped down and placed in the road.[46] At the top of Cotton Hill, Siber was able to see the pursuing Confederate forces. He left the 47th Ohio Infantry detachment with some companies from the 37th Ohio Infantry, with two mountain howitzers, to hold off the pursuing forces while the retreat continued. By that time, many of the Union soldiers were dumping any gear that might slow down their escape. Fighting at Cotton Hill continued until about noon, and then the Union force escaped to Montgomery's Ferry.[83] Lightburn's Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel Samuel A. Gilbert, left a detachment with artillery at Montgomery's Ferry to support Siber's retreat. Siber's supply wagons crossed the Kanawha River at that ferry, and joined the Second Brigade on the north side of the river. Gilbert's brigade, with Siber's wagons, retreated on the north side of the river toward Charleston, while Siber's brigade retreated down the south side of the river.[84]

Siber eventually crossed the river at Brownstown (now Marmet, West Virginia) and reunited with the Second Brigade.[85] At Charleston, Lightburn's two brigades fought the pursuing Confederate army on September 13 in the Battle of Charleston.[86] Lightburn's two brigades escaped from Charleston by burning the suspension bridge over the Elk River.[87] Shunning a route along the Kanawha River where he could be intercepted by Confederate cavalry lead by Jenkins, Lightburn took a road north to Ripley.[88] From there, he marched to Ravenswood, where on September 16 the Union troops crossed the Ohio River to the safety of the state of Ohio.[89] Loring remained in Charleston for about 40 days.[86] In early October, Cox was promoted to major general and sent back to retake the Kanawha River Valley.[90] By the end of October, Union forces retook control of the Kanawha Valley—including Charleston, Gauley Bridge, and Fayetteville.[91] Today, the battlefield at Fayetteville is now covered by a modern town.[92] Fayetteville has historical markers commemorating the 1862 battle and a second battle that occurred in 1863.[93] At least one soldier that was killed in the 1862 battle is buried in Fayetteville's Vandalia Cemetery.[94]

Result and casualties

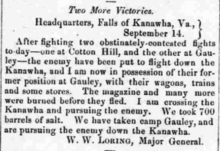

On September 14, Loring sent a general order congratulating his army "on its successive victories over the enemy at Fayette Court-House, Cotton Hill, and Charleston."[95] The battle should be considered a Confederate victory, since the Union force was driven away from the battlefield. However, one historian wrote "Both armies had been bloodied, but neither defeated."[79] A newspaper thought Siber deserved a general's commission.[96] A sergeant from the Confederate Bryan's Battery observed that Siber's force of only one regiment [with three companies cut off from the main force] plus six companies of another, with six artillery pieces, held off 5,000 men assisted by 16 pieces of artillery. The soldier thought that either Siber deserves credit for one of the more "brilliant feats of the war" or the Confederates had one of the most "dismal failures".[96] Siber praised Colonel Toland in his September 24 report.[97]

Initially, newspaper reports were positive concerning Lightburn's decision to retreat. The Cleveland Morning Leader said, "The retreat was undoubtedly a masterly movement, and does great credit to Colonel Lightburn."[98] However, Cox later wrote a different perspective. He mentions that "...either of the brigades intrenched at Gauley Bridge could have laughed at Loring. The river would have been impassable, for all the ferry-boats were in the keeping of our men on the right bank, and Loring would not dare pass down the valley leaving a fortified post on the line of communications by which he must return."[99]

Exact numbers for the Union casualties are difficult to tabulate, since Union reporting is for the entire campaign instead of only the Battle of Fayetteville.[Note 9] Siber's report did not list casualties, although he wrote that the "losses of the Thirty-seventh Regiment in these combats were insignificant in proportion to those of the Thirty-fourth, by reason of their having occupied the breastworks."[101] Based on one historian's research, Union casualties were 16 killed, 67 wounded, 46 missing, 6 captured, and 2 died from disease.[102] This totals to 137, and includes figures for the 34th Ohio Infantry (less two wounded at Charleston), the 37th Ohio Infantry, and 1 killed from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry. The 34th Ohio Infantry, with an adjusted total of 108 casualties at Fayetteville, had by far the most casualties.[102][Note 10] Confederate casualties reported were 16 killed, four mortally wounded, and 28 wounded.[79] These figures are from Loring's medical director who reported on September 15, and it was noted that the count for wounded only included those that could no longer move with the army.[105] Historian Lowry's research finds at least 15 killed, 6 mortally wounded, 63 wounded, 4 who died from illness. A total of at least 88 casualties at Fayetteville.[106]

See also

- List of West Virginia Civil War Confederate units

- List of West Virginia Civil War Union units

- West Virginia in the Civil War

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ As county seat and location of the county courthouse, Fayetteville was sometimes called "Fayette Court–House".[7] The United States census for 1850 does not list a population for Fayetteville, but reveals a total county population of 3,955.[6]

- ^ Cox would eventually become governor of Ohio and serve as United States Secretary of the Interior in the administration of president Ulysses S. Grant.[13]

- ^ The mountain howitzers were probably M1841 Pack Model versions because few alternatives existed.[25] Mountain howitzers were smaller and lighter than a full size cannon. The United States began producing howitzers in the 1830s, but those versions were short–lived until the Model 1841 Mountain Howitzer was produced. The Pack Model version could be disassembled and transported on three horses.[25]

- ^ Because of the mixed loyalties in Virginia, the state provided regiments for both the Union and Confederate armies. The 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry was a Union regiment, that should not be confused with the 2nd Virginia Cavalry Regiment that was in the Confederate army. After the state of West Virginia was created from the western portion of Virginia on June 20, 1863, the Union regiments from Virginia were renamed as West Virginia regiments, causing the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry to become the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry.[29]

- ^ While Lowry lists Derrick's Battalion (23rd Virginia Infantry Battalion) as with Wharton, Wharton's September 17 report does not mention it.[37][35] Lowry speculates that Derrick's Battalion was held in reserve.[38]

- ^ One author (Francis Lightburn Cressman) claims that Loring reported a force of only 5,000 men, which was lower than its actual size, to downplay his numerical advantage and make his victories appear as difficult accomplishments.[50]

- ^ At the time of the American Civil War, some of the small county seats were identified with the county name followed by "Court House". For example: Beckley, Virginia (later Beckley, West Virginia) is identified on some maps as "Beckley", but it is identified in other maps as "Raleigh C.H." or Raleigh Court House. Beckley is the county seat of Raleigh County.[59]

- ^ Toland's report listed casualties of one officer and 12 enlisted men killed, six officers and 74 enlisted men wounded, and one officer and 35 enlisted men missing.[72]

- ^ Dyer lists 310 casualties for Fayetteville, but notes that the total includes figures for the action at Cotton Hill.[100]

- ^ Total casualties are the sum of the casualties for the 34th and 37th Ohio infantries, with two removed from the wounded total and one added to the killed total. Historian Lowry's research concluded that all of the casualties for the 34th Ohio Infantry happened at Fayetteville with the exception of one soldier from Company D and one soldier from Company K, who were wounded at Charleston.[103] Lieutenant George Weir from the 2nd Loyal Virginia Cavalry was killed around midnight of September 10 near Loup Creek while assisting in the beginning of Siber's retreat.[79] Lowry did not find any casualties from the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry that occurred at Fayetteville.[104]

Citations

- ^ Snell 2012, Ch. 1 Loc. 157 of e-book

- ^ Snell 2012, Ch. 4 Loc. 796 of e-book

- ^ Snell 2012, Preface Loc. 66 of e-book

- ^ MacCorkle 1916, p. 271

- ^ Cox 1900, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b c "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – Fayetteville Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1080

- ^ a b c Lowry 2016, p. 99

- ^ Starr 1981, p. 154

- ^ Krebs, Teets & West Virginia Geological Survey 1914, p. 28

- ^ Cox 1900, pp. 63–64

- ^ Cox 1900, p. 59

- ^ "National Governors Association – Jacob Dolson Cox". National Governors Association. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Cox 1900, pp. 224–226

- ^ Cox 1900, pp. 225–226

- ^ a b c Cox 1900, p. 392

- ^ Cox 1900, p. 393

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 76

- ^ a b c Scott 1887, p. 1057

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 29

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1059

- ^ a b c Lowry 2016, p. 30

- ^ Troiani, Coates & McAfee 2006, p. 16

- ^ a b c Lowry 2016, p. 109

- ^ a b "The 1841 Mountain Howitzer". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 30–31

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 123

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 98

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. vi

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1079

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 5

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1081

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 10

- ^ a b Scott 1887, p. 1082

- ^ a b Scott 1887, p. 1088

- ^ a b Evans 1899, p. 65

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 110

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 116

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 22–23

- ^ Wallace 1986, p. 58

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 100

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 19

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 21

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 18–20

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, pp. 116–117

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 145

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 45

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 49

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 59

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 25

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 84

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 73

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 70

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 74–75

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 78–79

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 86

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 91

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 82

- ^ Guiley 2019, p. 206

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 94

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 92

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 108–109

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, pp. 110–111

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 111

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 113

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 114

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 119

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 120

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 124

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 125

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 129

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 131

- ^ a b c Lowry 2016, p. 135

- ^ Vance 1896, p. 121

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 133

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 134–135

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 136–137

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 142

- ^ a b c d e Lowry 2016, p. 138

- ^ a b Vance 1896, p. 123

- ^ Vance 1896, p. 122

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 141

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 152–153

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 158

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 174–175

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 181

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 204

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 208–209

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 248

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 299

- ^ Cox 1900, pp. 413–414

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 101

- ^ "West Virginia Archives and History – Battle of Fayetteville". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 121

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1072

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 137

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1060

- ^ "The Advance of the Rebels into the Kanawha Valley – Retreat of Colonel Lightburn (page 2 center column)". Cleveland Morning Leader (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 25, 1863. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ Cox 1900, pp. 396–397

- ^ Dyer 1908, p. 973

- ^ Scott 1887, p. 1063

- ^ a b Lowry 2016, p. 423

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 410–411

- ^ Lowry 2016, p. 409

- ^ Scott 1887, pp. 1080–1081

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 414–421

References

- Cox, Jacob Dolson (1900). Military Reminiscences of the Civil War Volume I – April 1861 – November 1863. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-3-84951-384-9. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Publishing Co. OCLC 1028851810. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- Evans, Clement A., ed. (1899). Confederate Military History: A library of Confederate States History.... (Volume II). Atlanta, Georgia: Confederate Publishing Company. OCLC 951143. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2019). Big Book of West Virginia Ghost Stories. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-1-49304-399-6. OCLC 1108619435.

- Krebs, Charles E.; Teets, D. D.; West Virginia Geological Survey (1914). Kanawha County. Wheeling, West Virginia: Wheeling News Lithograph Co. OCLC 1013164867.

- Lowry, Terry (2016). The Battle of Charleston and the 1862 Kanawha Valley campaign. Charleston, West Virginia: 35th Star Publishing. ISBN 978-0-96645-348-5. OCLC 981250860.

- MacCorkle, William Alexander (1916). The White Sulphur springs; the Traditions, History, and Social Life of the Greenbriar White Sulphur Springs. Charleston, West Virginia: W.A. MacCorkle. OCLC 11083303. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1887). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XIX Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Snell, Mark A. (2012). West Virginia and the Civil War : Mountaineers are Always Free. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-390-9. OCLC 1051048067.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1981). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 4492585.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- Troiani, Don; Coates, Earl J.; McAfee, Michael J. (2006). Don Troiani's Civil War Zouaves, Chasseurs, Special Branches, & Officers. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-81173-320-5. OCLC 61859726.

- Vance, John L. (1896). "The Retreat of the Union Forces from the Kanawha Valley in 1862". In Chamberlin, William Henry (ed.). Sketches of War History, 1861–1865: Papers Read Before the Ohio Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Volume IV. Cincinnati, Ohio: The Robert Clarke Company. pp. 118–132. OCLC 191708365. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- Wallace, Lee A. (1986). A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations 1861–1865. Lynchburg, Virginia: H.E. Howard, Inc. ISBN 978-0-93091-930-6. OCLC 1003746760.

External links

- Battle of Fayetteville Historical Marker

- Drawing of Fayetteville April 1863 – West Virginia University, West Virginia & Regional History Center

- List of West Virginia Civil War Battles – National Park Service