Pteridomania

Pteridomania or Fern-Fever was a Victorian craze for ferns. Decorative arts of the period presented the fern motif in pottery, glass, metal, textiles, wood, printed paper, and sculpture, with ferns "appearing on everything from christening presents to gravestones and memorials".[1]

Description

Pteridomania, meaning Fern Madness or Fern Craze, a compound of Pteridophytes and mania, was coined in 1855 by Charles Kingsley in his book Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore:

Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing 'Pteridomania'...and wrangling over unpronounceable names of species (which seem different in each new Fern-book that they buy)...and yet you cannot deny that they find enjoyment in it, and are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip, crochet and Berlin-wool.[1]

According to one author:

Although the main period of popularity of ferns as a decorative motif extended from the 1850s until the 1890s, the interest in ferns had really begun in the late 1830s when the British countryside attracted increasing numbers of amateur and professional botanists. New discoveries were published in periodicals, particularly The Phytologist: a popular botanical miscellany, which first appeared in 1844.[2] Ferns proved to be a particularly fruitful group of plants for new records because they had been studied less than flowering plants. Also, ferns were most diverse and abundant in the wilder, wetter, western and northern parts of Britain which were becoming more accessible through the development of better roads and the railway.[1]

Collection and cultivation

The collection of ferns drew enthusiasts from different social classes and it is said that "even the farm labourer or miner could have a collection of British ferns which he had collected in the wild and a common interest sometimes brought people of very different social backgrounds together."[1]

For some a fashionable hobby and for others a more serious scientific pursuit, fern collecting became commercialised with the sale of merchandise for fern collectors. Equipped with The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland or one of the many other books sold for fern identification, collectors sought out ferns from dealers and in their native habitats across the British Isles and beyond. Fronds were pressed in albums for display in homes. Live plants were also collected for cultivation in gardens and indoors. Nurseries provided not only native species but exotic species from the Americas and other parts of the world.[1]

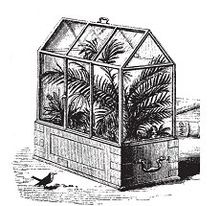

The Wardian case, a forerunner of the modern terrarium, was invented about 1829 by Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward to protect his ferns from the air pollution of 19th century London. Wardian cases soon became features of stylish drawing rooms in Western Europe and the United States and helped spread the fern craze and the craze for growing orchids that followed.[3] Ferns were also cultivated in fern houses (greenhouses devoted to ferns) and in outdoor ferneries.

Besides approximately seventy native British species and natural hybrids of ferns, horticulturalists of this era were very interested in so-called monstrosities – odd variants of wild species. From these they selected hundreds of varieties for cultivation. Polystichum setiferum, Athyrium filix-femina, and Asplenium scolopendrium, for example, each yielded about three hundred different varieties.[1][4]

Decorative art

Fern motifs first became conspicuous at the 1862 International Exhibition and remained popular "as fond symbol of pleasurable pursuits" until the turn of the century.[1]

As fern fronds are somewhat flat they were used for decoration in ways that many other plants could not be. They were glued into collectors' albums, affixed to three dimensional objects, used as stencils for "spatter-work", inked and pressed into surfaces for nature printing, and so forth.[1]

Fern pottery patterns were introduced by Wedgwood, Mintons Ltd, Royal Worcester, Ridgeway, George Jones, and others, with various shapes and styles of decoration including majolica. A memorial to Sir William Jackson Hooker, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew was commissioned from Josiah Wedgwood and Sons and erected in Kew Church in 1867 with jasperware panels with applied sprigs representing exotic ferns. A copy was presented to what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum where it may still be seen.[1]

While realistic depictions of ferns were especially favoured in the decorative arts of this period, "Even when the representation was stylised such as was common on engraved glass and metal, the effect was still recognisably 'ferny'."[1]

Other species

Selaginella and Lycopodiopsida and other fern ally plants were also collected and represented on decorative objects.[1]

Effects on native populations

The zeal of Victorian collectors led to significant reductions in the wild populations of a number of the rarer species. Oblong Woodsia came under severe threat in Scotland, especially in the Moffat Hills. This area once had the most extensive UK populations of the species but there now remain only a few small colonies whose future remains under threat. The related Alpine Woodsia suffered a similar fate, although the risks were not all to the plants. John Sadler, later a curator of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, nearly lost his life obtaining a fern tuft on a cliff near Moffat, and a botanical guide called William Williams died collecting Alpine Woodsia in Wales in 1861. His body was found at the foot of the cliff where Edward Lhwyd had first collected the species nearly two centuries earlier.[5] In her botanical guidebook and memoir Hardy Ferns (1865), the writer Nona Bellairs called for laws to protect ferns from over-collection: "We must have 'Fern laws', and preserve them like game".[6]

The Killarney Fern, considered to be one of Europe's most threatened plants[7] and once found on Arran, was thought to be extinct in Scotland due to the activities of 19th century collectors, but the species has since been discovered on Skye in its gametophyte form.[8][9] Dickie's Bladder-fern, which was discovered growing on base-rich rocks in a sea cave on the coast of Kincardineshire in 1838.[10] By 1860 the original colony seemed to have been extirpated, although the species has recovered and today there is a population of more than 100 plants there, where it grows in a roof fissure.[11][12]

Outside the United Kingdom

Pteridomania is "usually considered a British eccentricity",[13] and historians are divided regarding its reach outside the United Kingdom. John D. Scott has written:

The craze seemed to have passed America by – most likely because these same species in America are essentially free of these "freaky" abnormal forms. It may also be due to the fact the American botanists have been for the most part more interested in unravelling the complexities of the species involved in the fern complexes such as Asplenium, Dryopteris, and Botrychium.[14]

On the other hand, historian Sarah Whittingham has "turned up much proof that it reached American shores"[13] in her book, Fern Fever: The Story of Pteridomania.[15] The American Fern Society was established in 1893 and now has over 900 members worldwide. The society is based at Indiana University and counts itself as "one of the largest international fern clubs in the world."[16] William Ralph Maxon served repeatedly as the society president.[17]

The Dorrance H. Hamilton Fernery at the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania is the only remaining freestanding Victorian fernery in North America. It has a curved Victorian-style glass roof and turned 100 years old in 1999. Designed by John Morris, the arboretum's namesake, the Fernery is said to embody "some of the many passions of the Victorians: a love of collecting, a veneration of nature, and the fashion of romantic gardens....its filigree roof sparkling in sunlight.[18]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Boyd (1993).

- ^ George Luxford; Edward Newman (1 January 1841). The Phytologist: a popular botanical miscellany. John van Voorst. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Biography of Dr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward". Plantexplorers.com. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Boyd (2005).

- ^ Lusby and Wright (2002) pp. 107–09.

- ^ Bellairs, Nona. Hardy Ferns: How I Collected and Cultivated Them. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1865, p. 77.

- ^ "Species Recovery Programme" English Nature. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ Ratcliffe (1977), p. 40.

- ^ "Skye Flora". plant-identification.co.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ Lusby and Wright (2002) pp. 35–37.

- ^ Lusby and Wright (2002) p. 109.

- ^ "Cystopteris dickieana" Scottish plant uses. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ a b Kahn, Eve M. (15 March 2012). "19th-Century Fern Fever, in England and Beyond". The New York Times.

- ^ Scott, John D. (November 2001). "The Victorian Fern Craze and the American Christmas Fern" (PDF). Dodecatheon. Scott is associated with the Rockland Botanical Garden in Mertztown, Pennsylvania; Dodecatheon is the newsletter of the Delaware Valley Chapter of the North America Rock Garden Society.

- ^ Whittingham (2012).

- ^ American Fern Society

- ^ Smithsonian Institution Archives

- ^ "The Dorrance H. Hamilton Fernery". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007.

Bibliography

- Allen, D. E. (1969). The Victorian Fern Craze: A History of Pteridomania. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 9780090998708. OCLC 62148.

- Boyd, Peter D. A. (1993). "Pteridomania – the Victorian passion for ferns". Revised: web version. 28 (6). Antique Collecting: 9–12. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) The online version, dated 2 January 2002, has been revised from the published version. - Boyd, Peter D. A. (Winter 2005). "Ferns and Pteridomania in Victorian Scotland". The Scottish Garden: 24–29. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Hershey, David (1996). "Doctor Ward's Accidental Terrarium". The American Biology Teacher. 58: 276–281. doi:10.2307/4450151.

- Lusby, Phillip and Wright, Jenny (2002). Scottish Wild Plants: Their History, Ecology and Conservation. Edinburgh: Mercat. ISBN 1-84183-011-9.

- Ratcliffe, Derek (1977). Highland Flora. Inverness: HIDB.

- Whittingham, Sarah (2009). The Victorian Fern Craze. Shire. ISBN 978-0-7478-0746-9

- Whittingham, Sarah (2012). Fern Fever: The Story of Pteridomania. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3070-5. OCLC 741539015.