Stiffelio

| Stiffelio | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Giuseppe Verdi | |

| |

| Librettist | Francesco Maria Piave |

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | Le pasteur, ou L'évangile et le foyer by Émile Souvestre and Eugène Bourgeois |

| Premiere | 16 November 1850 Teatro Grande, Trieste |

Stiffelio is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi, from an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave. The origin of this was the novel Le pasteur d’hommes, by Émile Souvestre, which was published in 1838. This was adapted into the French play Le pasteur, ou L'évangile et le foyer by Émile Souvestre and Eugène Bourgeois. That was in turn translated into Italian by Gaetano Vestri as Stifellius; this formed the basis of Piave's libretto.[1]

Verdi's experience in Naples for Luisa Miller had not been a good one and he returned home to Busseto to consider the subject for his next opera. The idea for Stiffelio came from his librettist and, entering into a contract with his publisher, Ricordi, he agreed to proceed, leaving the decision as to the location of the premiere to Ricordi. This became the Teatro Grande (now the Teatro Comunale Giuseppe Verdi) in Trieste and, in spite of difficulties with the censors which resulted in cuts and changes, the opera – Verdi's 16th – was first performed on 16 November 1850.

Composition history

Before Luisa Miller was staged in Naples, Verdi had offered the San Carlo company another work for 1850, with the new opera to be based on Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse from a libretto to be written by Salvadore Cammarano. But his experience with Luisa was such that he decided not to pursue this, and approached his publisher, Giulio Ricordi, with the proposal that he should work with the librettist on the possibility of an opera, Re Lear, which would be based on Shakespeare's King Lear and which had long been on Verdi's mind. However, by June 1850 it became clear that the subject was beyond Cammarano's ability to fashion into a libretto, and so it was abandoned. However, the commitment to Ricordi remained.[2]

Verdi had returned to Busseto with many ideas in mind, among them a new opera for Venice, which included a request for a draft scenario from Piave based on Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse.[1] plus several others of interest to him. However, it was the librettist who came back with the suggestion of Stifellius, and between March and May 1850 discussions with Piave proceeded until a sketch of Stiffelio was received. Verdi responded enthusiastically, proclaiming it "good and exciting" and asking: "Is this Stiffelio a historical person? In all the history I've read, I don't remember coming across the name."[3] At the same time, it appears that Verdi continued to be fascinated by Le Roi s'amuse, a play which Budden notes as having been banned at its first performance: "it was, politically speaking, dynamite" but he adds that the Venetian censors had allowed Ernani.[2]

Reactions to the choice of subject and how it worked as a libretto and opera have been fairly uniform. Musicologist Roger Parker in Grove describes it as:

- A bold choice, a far cry from the melodramatic plots of Byron and Hugo: modern, 'realistic', subjects were unusual in Italian opera, and the religious subject matter seemed bound to cause problems with the censor. [...] The tendency of its most powerful moments to avoid or radically manipulate traditional structures has been much praised.[4]

Budden basically agrees, stating that "[Verdi] was tired of stock subjects; he wanted something with genuinely human, as distinct from melodramatic, interest. [....] Stiffelio had the attraction of being a problem play with a core of moral sensibility; the same attraction, in fact, that led Verdi to La traviata a little later.[2]

As Stiffelio moved towards completion, Ricordi decided that it should be performed in Trieste. As the premiere approached, both librettist and composer were called before the president of the theatre commission on 13 November, given that the organization had received demands for changes from the censor, which included a threat to block the production entirely if these were not met. The original story line of Stiffelio, involving as it does a Protestant minister of the church with an adulterous wife, and a final church scene in which he forgives her with words quoted from the New Testament, was impossible to present on the stage, and this created these censorship demands for various reasons: "In Italy and Austrian Trieste ... a married priest was a contradiction in terms. Therefore there was no question of a church in the final scene...."[5]

The changes which were demanded included Stiffelio being referred to not as a minister, but as a "sectarian". Furthermore, in act 3, Lina would not be allowed to beg for confession, plus as Budden notes, "the last scene was reduced to the most pointless banality" whereby Stiffelio is only permitted to preach in general terms.[2] Both men were reluctantly forced to agree to accept the changes.

Performance history

The different versions

In the introduction to the critical edition[6] prepared in 2003 by Kathleen Hansell, she states quite clearly that "The performance history of Stiffelio as Verdi envisioned it literally began only in 1993."[7]

She might have added "21 October 1993", since this was the occasion when the Metropolitan Opera presented the work based on the discoveries which had been found in the composer's autograph manuscript by musicologist Philip Gossett the previous year[8] and which were eventually included in the critical edition prepared by her for the University of Chicago in 2003.

In setting the context of the re-creation of the opera, Hansell states:

- This opera, composed in tandem with Rigoletto and sharing many of its forward-looking characteristics, suffered even more than Rigoletto from the censors' strictures. The story of [the opera...] shocked conservative post-Revolutionary Italian religious and political powers. From its very premiere at Trieste in November 1850, its text was diluted to appease the authorities, making a mockery of the action and thus of Verdi's carefully calibrated music. The libretto was rewritten for subsequent revivals, and even some of Verdi's music was dropped.[7]

Hansell's statement establishes what happened to Verdi's opera in the years between the 1850 premiere and October 1993. To begin with, a revised version of the opera, entitled Guglielmo Wellingrode (with the hero a German minister of state),[2] was presented in 1851, without either Verdi or his librettist Piave being responsible for it.[9] In fact, when asked by impresario Alessandro Linari in 1852 to create a more suitable ending, Verdi was furious and refused.[2] In addition, it is known that some productions were given in the Iberian peninsula in the 1850s and 1860s.[10]

Verdi withdraws Stiffelio in 1856; the autograph disappears

As early as 1851, it became clear to Verdi that given the existing censorship throughout Italy, there was no point in Ricordi, his publisher and owner of the rights to the opera, trying to obtain venues for performances before the composer and librettist together had any opportunity to revise and restructure it more acceptably.[11] However, in her research for the critical edition, Hansell notes that in 1856 Verdi angrily withdrew his opera from circulation, reusing parts of the score for his reworked 1857 version, the libretto also prepared by Piave: it was renamed as Aroldo and set in 13th century Anglo-Saxon England and Scotland. It contains a totally new fourth act.[7]

Throughout the rest of the 19th century and for most of the 20th, the Stiffelio autograph was generally presumed to be lost.

20th century performances before October 1993

Hansell is clear on several points regarding any performances between 1856 and October 1993:

- All previous modern editions, including the score prepared by Edward Downes and first performed in January 1993 by The Royal Opera company at Covent Garden, were based largely or entirely on secondary sources, such as the early printed vocal score and defective 19th-century manuscript copies of the full score. For the Covent Garden performances, with José Carreras as Stiffelio, Philip Gossett made preliminary corrections of the vocal parts only, based on the newly recovered autograph materials.[7]

Although vocal scores were known, the discovery of a copyist's score at the Naples Conservatory in the 1960s led to a successful revival at the Teatro Regio in Parma in 1968.[9][12]

A new performing edition, prepared for Bärenreiter from microfilm of the Naples copyist's score, was obtained in order to restore the composer's intentions as far as possible. This was the basis of performances at Naples and Cologne, but it cut material (especially from the act 1 overture and choruses) and it added in sections from Aroldo, which were not in the original score. This became the source of the UK premiere in an English language production given by University College Opera (then the Music Society) in London in 1973.[13] [14] Given that even the original premiere of the work was in a version partly cut by the censors, this production was probably one of the first ever close-to- authentic performances of the work.[13]

The American stage premiere was given by Vincent La Selva and the New York Grand Opera on 4 June 1976 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music with Richard Taylor as Stiffelio and Norma French as Lina.[15][16] The opera was also given by Sarah Caldwell and the Opera Company of Boston on 17 February 1978.[14][17][18]

The Stiffelio autograph found; The Met presents the "new" Stiffelio; the critical edition prepared

In his book, Divas and Scholars, Philip Gossett, the General Editor of the critical editions of the Verdi operas published by the University of Chicago, tells the story of how "to [his] immense joy" the original Verdi materials came to be seen by him in February 1992 when the Carrara Verdi family allowed access to the autograph and to copies of about 60 pages of supplementary sketches.[19] Some aspects of the original Verdi edition were able to be shared with Edward Downes for his 1993 staging in London, but these included only the vocal elements and none of the orchestral fabric, for which Downes' edition relied entirely on a 19th-century copy.[7]

The first complete performance of the new score was given on 21 October 1993 at the Metropolitan Opera house in New York.[20][21] The production was repeated 16 more times between October 1993 and 1998, at which time a DVD with Plácido Domingo in the title role was released.[22]

In 1985–1986 the Teatro La Fenice in Venice mounted back-to-back productions of Aroldo and Stiffelio (the latter in a version similar to that described above) in conjunction with an international scholarly conference which was held in that city in December 1985.[9][23]

The 1993 Met production was revived in 2010 with José Cura in the title role and conducted by Domingo.[24][25] The new critical edition has also been performed at La Scala and in Los Angeles.[7]

The Sarasota Opera presented Stiffelio in 2005 as part of its "Verdi Cycle" of all of the composer's operas.[26][27] The opera was given in a concert version in London by the Chelsea Opera Group on 8 June 2014 with the role of Lina being sung by Nelly Miricioiu.[28] The Berlin premiere of Stiffelio was conducted by Felix Krieger with Berliner Operngruppe on February 1st 2017 at Konzerthaus Berlin. New productions of the opera were presented by Frankfurt Opera and La Fenice, Venice in 2016, by Teatro Regio di Parma in 2017 and at Palacio de Bellas Artes in 2018.[29]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 16 November 1850[30] (Conductor: -) |

|---|---|---|

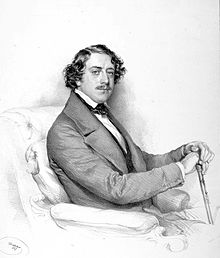

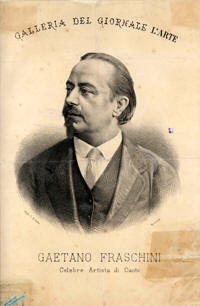

| Stiffelio, a Protestant minister | tenor | Gaetano Fraschini |

| Lina, his wife | soprano | Marietta Gazzaniga |

| Count Stankar, her father, an elderly colonel | baritone | Filippo Colini |

| Raffaele, Lina's lover | tenor | Ranieri Dei |

| Jorg, an elderly minister | bass | Francesco Reduzzi |

| Dorotea, Lina's cousin | mezzo-soprano | Viezzoli De Silvestrini |

| Federico, Dorotea's lover | tenor | Giovanni Petrovich |

Synopsis

- Place: Count Stankar's castle by the River Salzbach, Germany

- Time: Early 19th Century

Act 1

Scene 1: A hall in Count Stankar's castle

Stiffelio, a Protestant priest or minister, is expected to return from a mission. His wife Lina, her father Stankar, and her cousins Dorotea and Federico are waiting for him. In addition, there is Raffaele who, unknown to all, is Lina's lover. Stiffelio arrives and recounts how the castle's boatman has told him the strange story of having seen a man and a woman escaping from a castle window and, as they did so, dropping a packet of letters, which Stiffelio now holds. Refusing to learn by opening the package who was involved, he throws the letters into the fire, much to the relief of Lina and Raffaele. Secretly, Raffaele communicates to Lina that he will leave instructions as where they may next meet inside a locked volume in the library.

After he has been greeted by friends, Lina and Stiffelio are left alone (Non ha per me un accento – "She has no word for me, not a glance"). He tells her of the sin he has witnessed (Vidi dovunque gemere – "Everywhere I saw virtue groan beneath the oppressor's yoke") and then notices that her wedding ring is not on her finger. Angrily, he demands to know why (Ah v'appare in fronte scritto – "Ah, clearly written on your brow is the shame that wages war in your heart"), but Stankar arrives to escort him to the celebrations being arranged by his friends. Alone, Lina is filled with remorse (A te ascenda, O Dio clemente – "Let my sighs and tears ascend to thee, O merciful God").

Scene 2: The same, later

Deciding to write a confession to Stiffelio, Lina begins to write, but her father enters and grabs the letter, which he reads aloud. Stankar rebukes her (Dite che il fallo a tergere – "Tell him that your heart lacks the strength to wash away your sins", but is determined to preserve family honor and cover up his daughter's behavior (Ed io pure in faccia agli uomini – "So before the face of mankind I must stifle my anger"). In their duet, father and daughter come to some resolve (O meco venite – "Come now with me; tears are of no consequence") and they leave.

Now Raffaele enters to place the note in the volume, which has been agreed to. Jorg, the elderly preacher, observes this just as Federico arrives to take the volume away. Jorg's suspicions fall upon Federico and he shares what he knows with Stiffelio. Seeing the volume and realizing that it is locked, he is told that Lina has a key. She is summoned, but when she refuses to unlock it, Stiffelio grabs it and breaks it open. The incriminating letter falls out, but it is quickly taken up by Stankar and torn into many pieces, much to the fury of Stiffelio.

Act 2

A graveyard near the castle

Lina has gone to her mother's grave at the cemetery to pray (Ah dagli scanni eterei – "Ah, from among the ethereal thrones, where, blessed, you take your seat"), but Raffaele joins her. She immediately asks him to leave. He laments her rejection (Lina, Lina! Perder dunque voi volete – "Lina, then you wish to destroy this unhappy, betrayed wretch") and refuses to go (Io resto – "I stay"). Stankar arrives, demands that his daughter leave, and then challenges Raffaele to a duel. Stiffelio arrives, and announces that no fighting can take place in a cemetery. There is an attempt at conciliation whereby the priest takes Stankar's hand and then Raffaele's, joining them together. However, Stankar reveals that Stiffelio has touched the hand of the man who betrayed him! Not quite understanding at first, Stiffelio demands that the mystery be solved. As Lina returns demanding her husband's forgiveness, Stiffelio begins to comprehend the situation (Ah, no! E impossibile – "It cannot be! Tell me at least that it is a lie"). Demanding an explanation, he challenges Raffaele to fight but, as he is about to strike the younger man, Jorg arrives to summon the priest to the church from which the sound of the waiting congregation can be heard. Filled with conflicting emotions, Stiffelio drops his sword, asks God to inspire his speech to his parishioners, but, at the same time, curses his wife.

Act 3

Scene 1: A room in Count Stankar's Castle

Alone in his room, Stankar reads a letter which tells him that Raffaele has fled and that he seeks to have Lina join him. He is in despair over his daughter's behaviour (Lina pensai che un angelo in te mi desse il cielo – "Lina, I thought that in you an angel brought me heavenly bliss"). For a moment, he resolves to commit suicide and begins to write a letter to Stiffelio. But Jorg enters to give him the news that he has tracked down Raffaele who will be returning to the castle. Stankar rejoices (O gioia inesprimibile, che questo core inondi! – "Oh, the inexpressible joy that floods this heart of mine!"), as he sees revenge being within reach. He leaves.

Stiffelio confronts Raffaele and asks him what he would do if Lina were free, offering him a choice between "a guilty freedom" and "the future of the woman you have destroyed". The younger man does not respond, and the priest tells him to listen to his encounter with Lina from the other room. Stiffelio lays out the reason that their marriage can be annulled (Opposto è il calle che in avvenire – "Opposite are the paths that in future our lives will follow"). Lina's reaction, when presented with the divorce decree, is to swear an ongoing love for her husband ("I will die for love of you"). Appealing to Stiffelio more as a priest than as a husband, Lina confesses that she has always loved him and she still does. Stankar enters to announce that he has killed Raffaele. Jorg tries to convince Stiffelio to come to the church service (Ah sì, voliamo al tempio – "Ah, yes, let us flee to the church").

Scene 2: A church

In the church, Stiffelio mounts the pulpit and opens the Bible to the story of the adulterous woman (John 7:53–8:11). As he reads the words of forgiveness (perdonata) he looks at Lina and it is clear that she too is forgiven.

Instrumentation

Stiffelio is scored for the following instruments:[7]

- 1 flute (doubling on piccolo),

- 2 oboes (one doubling on English horn),

- 2 clarinets,

- 2 bassoons,

- 4 horns,

- 2 trumpets,

- 3 trombones,

- cimbasso,

- timpani,

- snare drum,

- bass drum,

- cymbals,

- organ,

- strings (violin I and II, viola, cello, double bass)

Music

Reviews following the premiere were rather mixed, although Budden seems to suggest that there were more unfavorable ones than the reverse.[31] However, one contemporary critic, writing in the Gazzetta Musicale states:

- This is a work at once religious and philosophical, in which sweet and tender melodies follow one another in the most attractive manner, and which achieves...the most moving dramatic effects without having recourse to bands on the stage, choruses or superhuman demands on vocal cords or lungs.[32]

When addressing the music of this opera, several writers refer to its unusual features and the ways by which it suggests directions in which the composer is moving and as seen in later operas. For example, when comparing both versions, Osborne states that act 1, scene 2 of Stiffelio "is almost Otello-like in its force and intensity, while Kimball states directly that "Verdi's music, in keeping with the dramatic theme, is as boldly unconventional as anything he had composed"[33] and he continues, in referring to the Bible reading scene in the finale, that it:

- marks the most radical break with the stylistic conventions of the day: its single lyrical phrase, the climactic 'Perdonata! Iddio lo pronunziò', stands out electricfyingly from an austere context of recitative intonation and quietly reiterated instrumental ostinati.[33]

Osborne agrees when he describes the narrative and musical action moving in tandem in the last act:

- Stiffelio preaches the gospel story of the woman taken in adultery, which he narrates in recitative. When he is suddenly moved to forgive Lina, his voice rises from the narrative chant to his top A on "Perdonata". The congregation echoes him, Lina ecstatically thanks God with her top C, and the curtain falls".[34]

Gabriele Baldini's The Story of Giuseppe Verdi deals with Stiffelio and Aroldo together, so the former gets rather limited mention. But in regard to the music, he makes a point about how:

- the act 1 soprano and baritone duet [O meco venite / "Come now with me; tears are of no consequence"] for example, contains the germ of several ideas which later expand the Rigoletto quartet. The dark instrumental introduction and broad, passionate arioso which opens act 2, finding the woman alone in an 'ancient cemetery', constitute a sort of dress rehearsal for the beginning of Un ballo in maschera's second act and the final scene of La forza del destino: it is no accident that, musically speaking, these are the best sections of both operas.[35]

Recordings

| Year | Cast (Stiffelio, Lina, Stankar, Jorg) |

Conductor, Opera House and Orchestra |

Label[36] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Gastone Limarilli, Angeles Gulin, Walter Alberti, Beniamino Prior |

Peter Maag, Teatro Regio di Parma orchestra and chorus |

Audio CD: Melodram Milano Cat: CDM 27033 |

| 1979 | José Carreras, Sylvia Sass, Matteo Manuguerra, Wladimiro Ganzarolli |

Lamberto Gardelli, ORF Symphony orchestra and chorus |

Audio CD: Decca Cat: 475 6775 |

| 1993 | José Carreras, Catherine Malfitano, Gregory Yurisich, Gwynne Howell |

Edward Downes, Royal Opera House orchestra and chorus |

DVD: Kultur Cat: D1497 |

| 1993 | Plácido Domingo, Sharon Sweet, Vladimir Chernov, Paul Plishka |

James Levine, Metropolitan Opera orchestra and chorus |

DVD: Deutsche Grammophon Cat: 00440 073 4288 |

| 2001 | Mario Malagnini, Dimitra Theodossiou, Marco Vratogna, Enzo Capuano |

Nicola Luisotti, Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi, Trieste |

Audio CD: Dynamic Cat: CDS362 |

| 2012 | Roberto Aronica, Yu Guanqun, Roberto Frontali, George Andguladze |

Andrea Battistoni, Teatro Regio di Parma orchestra and chorus |

DVD:C Major Cat:723104[37] |

References

Notes

- ^ a b Philips-Matz, p. 256

- ^ a b c d e f Budden, pp. 449 – 453

- ^ Verdi to Piave, 8 May 1850, in Budden, p. 450 – 451

- ^ Parker, pp. 542 – 543

- ^ Budden, "Aroldo: an opera remade", in the booklet accompanying the audio CD recording

- ^ Gossett, pp. 134 – 135: He defines a critical edition as a work which "looks at the best texts that modern scholarship, musicianship, and editorial technique can produce" [.....] but "they do not return blindly to one 'original' source, [they] reconstruct the circumstances under which an opera was written, the interaction of the composer and librettist, the effect of imposed censorship, the elements that entered into the performance, the steps that led to publication, and the role the composer played in the subsequent history of the work."

- ^ a b c d e f g Hansell, "Introduction" to the Critical Edition, University of Chicago

- ^ In Gossett: He describes it as "the manuscript of an opera primarily or entirely in the hand of the composer", p. 606

- ^ a b c Lawton, David, "Stiffelio and Aroldo", Opera Quarterly 5 (23): 193, 1987.

- ^ Gossett, Philip (2008). "New sources for Stiffelio: A preliminary report", Cambridge Opera Journal, 5:3, pp. 199–222.

- ^ Verdi to Ricordi, 5 January 1851, in Budden, p. 453

- ^ "Metropolitan Opera Broadcast: Stiffelio Broadcast of January 30" in Opera News, 74:8 (February 2010). Accessed 7 February 2010.

- ^ a b Performance programme, 14 February 1973, University College, London.

- ^ a b David Kimball, in Holden, p. 990

- ^ Ericson, Raymond, "Music: Verdi's 'Stiffelio'. La Selva leads New York Grand Opera in intimate revival in Brooklyn" The New York Times, 6 June 1976. (Registration and purchase required) Accessed 28 January 2010.

- ^ NYGO's web site. Archived December 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kessler, p. 236

- ^ Caldwell & Matlock, pp. 5, 226

- ^ Gossett, pp. 162 – 163

- ^ Rothestein, Edward (October 23, 1993). "Review/Opera; New to the Met: Verdi's 'Stiffelio,' From 1850". The New York Times.

- ^ Performance of Stiffelio on 21 October 1993 at the Met Opera Archive. Accessed 28 January 2010.

- ^ Performances of Stiffelio conducted by James Levine on the Met Opera Archive. Accessed 28 January 2010.

- ^ The proceedings of the international congress have been published in Italy, edited by Giovanni Morelli under the title Tornando a Stiffelio: popolarita, rifadimenti, messinscena e altre, 'cure' nella drammaturgia del Verdi romantico, (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1987).

- ^ Metropolitan Opera Playbill, 23 January 2010

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony "Music Review. 'Stiffelio': A Wife’s Betrayal, a Husband’s Internal Seething", The New York Times, 12 January 2010. Accessed 28 January 2010.

- ^ A video clip from the production can be seen on You-Tube

- ^ "Verdi Cycle – Sarasota Opera" at sarasotaopera.org

- ^ Colin Clarke, "Chelsea Opera Group’s Excellent Revival of Rare Verdi", 14 June 2014, on seenandheard-international.com. Retrieved 16 June 2014

- ^ "Stiffelio". Operabase. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ List of singers taken from Budden, p. 448.

- ^ Budden, p. 453

- ^ Gazzetta Musicale, 4 December 1850, in Osborne, p. 214

- ^ a b Kimbell, in Holden, p. 990

- ^ Osborne, p. 222

- ^ Baldini, pp. 242 – 243

- ^ Recordings on operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- ^ "Stifellio". Naxos.com. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

Cited sources

- Baldini, Gabriele (1970), (trans. Roger Parker, 1980), The Story of Giuseppe Verdi: Oberto to Un Ballo in Maschera. Cambridge, et al: Cambridge University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-521-29712-5

- Budden, Julian (1984), The Operas of Verdi, Volume 1: From Oberto to Rigoletto. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-31058-1.

- Caldwell, Sarah & Rebecca Matlock (2008), Challenges: A Memoir of My Life in Opera, Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6885-4.

- Gossett, Philip (2006), Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera, Chicago: University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-30482-3 ISBN 0-226-30482-5

- Hansell, Kathleen Kuzmick (2003), "Introduction to the Critical Edition of Stiffelio, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press and Milan: Casa Ricordi.

- Kessler, Daniel (2008). Sarah Caldwell; The First Woman of Opera, p. 236. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-6110-0

- Kimbell, David, in Holden, Amanda (Ed.) (2001), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4

- Osborne, Charles (1969), The Complete Opera of Verdi, New York: Da Capo Press, Inc. ISBN 0-306-80072-1

- Parker, Roger, "'Stiffelio" in Stanley Sadie, (Ed.) (2008), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. Four. London: MacMillan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

Other sources

- Chusid, Martin, (Ed.) (1997), Verdi’s Middle Period, 1849 to 1859, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-10658-6 ISBN 0-226-10659-4

- De Van, Gilles (trans. Gilda Roberts) (1998), Verdi’s Theater: Creating Drama Through Music. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14369-4 (hardback), ISBN 0-226-14370-8

- Martin, George, Verdi: His Music, Life and Times (1983), New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. ISBN 0-396-08196-7

- Parker, Roger (2007), The New Grove Guide to Verdi and His Operas, Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531314-7

- Pistone, Danièle (1995), Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera: From Rossini to Puccini, Portland, OR: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-82-9

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (1993), Verdi: A Biography, London & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-313204-4

- Toye, Francis (1931), Giuseppe Verdi: His Life and Works, New York: Knopf

- Walker, Frank, The Man Verdi (1982), New York: Knopf, 1962, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87132-0

- Warrack, John; West, Ewan (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Opera New York: OUP. ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- Werfel, Franz and Stefan, Paul (1973), Verdi: The Man and His Letters, New York, Vienna House. ISBN 0-8443-0088-8

External links

![]() Media related to Stiffelio at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stiffelio at Wikimedia Commons

- Template:Operabase

- Verdi: "The story" and "History" on giuseppeverdi.it (in English)

- Italian libretto from giuseppeverdi.it